St Giles' Church, Wrexham

St Giles' Parish Church (Welsh: Eglwys San Silyn) is the parish church of Wrexham, Wales. The church is recognised as one of the finest examples of ecclesiastical architecture in Wales and is a Grade I listed building, described by Sir Simon Jenkins as 'the glory of the Marches'[1] and by W. D. Caröe as a 'glorious masterpiece'.[2]

| St Giles' Church | |

|---|---|

| The Parish Church of St Giles | |

"The Glory of the Marches". | |

| |

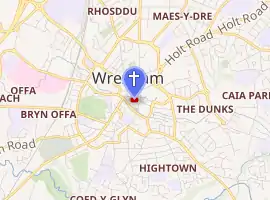

| Location | Church Street, Wrexham, LL13 8LS |

| Country | Wales |

| Denomination | Church in Wales |

| Website | St Giles' Church |

| History | |

| Status | Active |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Parish church |

| Heritage designation | Grade I listed |

| Style | Perpendicular |

| Years built | c. 16th century |

| Administration | |

| Parish | Wrexham |

| Diocese | Diocese of St Asaph |

| Clergy | |

| Vicar(s) | The Revd Dr Jason Bray (Vicar of Wrexham) |

| Curate(s) | The Rev James Tout |

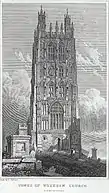

The iconic 16th century tower rises to a height of 136 feet[3] and is a local landmark that can be seen for many miles around. It forms one of the 'Seven Wonders of Wales'.

St Giles' occupies a site of continuous Christian worship for at least 800 years.[4] The main body of the current church was built at the end of the 15th century and beginning of the 16th centuries. It is widely held to be among the greatest of the medieval buildings still standing in Wales.[5]

The church contains numerous works of note including decorative carvings and statuary dating from the 14th century, monuments by Roubiliac and Woolner, a stained glass window attributed to Burne-Jones and one of the oldest brass eagle lecterns in Britain.[6]

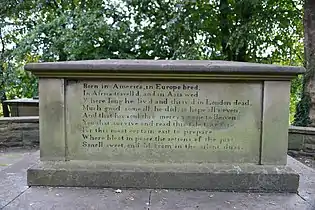

The tomb of Elihu Yale, benefactor of Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, is located in the churchyard. In recognition of this connection, 'Wrexham Tower' of Saybrook College in the university was modelled on the tower of St Giles'.[7][8]

History

A chapel in this area is believed to have been founded by the Celtic saint Silin (also known as 'Silyn').[9] A reference in 1620 to a piece of land called Erw Saint Silin (‘St Silin’s acre’) in the township of Acton in Wrexham Parish, highlights the saint’s importance in the area.[10] Both 'Silin' and 'Giles' can be translated into Latin as Aegidius and by 1494 the Church was known as 'Saint Giles'.

There may have been a church in the town as far back as the 11th century and the present church is likely the third to have been built on the site. The earliest reference to the church was 1220 when the Bishop of St Asaph gave the monks of Valle Crucis in Llangollen 'half of the [income of the] church ' of the town of Wrexham.[11] In 1247, Madoc ap Gruffydd, Prince of Powys, bestowed upon the monks of Valle Crucis the patronage of the church of Wrexham.

In 1330, the church tower was blown down by severe gales which resulted in a new church being rebuilt on the site in the decorated style, some features of which form the basis of the outline of the nave and aisles of the current 15th century building.[12] Either in 1457 or 1463, the church was gutted by fire and work on the present building was started on the same site and incorporated some features of the 14th century church, such as the octagonal pillars.

The main part of St Giles was built between the end of the 15th and early part of the 16th Century. The magnificent ornamentation is rich in dynastic Tudor symbolism and was likely financed by Lady Margaret Beaufort, mother of King Henry VII and husband to Thomas Stanley whose family had strong connections with the Wrexham area.

In 1643 soldiers of the Parliamentary army destroyed the original organ which was referred to as 'Ye fayrest organes in Europe'.[13]

In the 18th century, the church was depicted by JMW Turner[14][15] and described by Samuel Johnson as a 'very large and magnificent church'.[16]

Part of the church used to be Wrexham's first fire station there were no fire appliances, people would run from the town to collect ropes, water, and ladders and would run back.

In 2015, a rare first edition King James Bible from 1611 was rediscovered after centuries of storage in the church.[17]

Architecture and artworks

.jpg.webp)

The richly decorated five-stage tower, 135-feet high, with its four striking hexagonal turrets, was begun in 1506 and is ascribed to William Hart of Bristol.[18] An example of the Somerset type, it contains 30 niches and is graced by many statues and carvings including those of an arrow and a deer, the attributes of Saint Giles. It is thought that the tower may have been an inspiration for Victoria Tower, at the Palace of Westminster.[19][20][21]

The nave arcade is in the Decorated style, and dates from the 14th century, but the remainder of the church is in the late Perpendicular style, and includes an unusual polygonal chancel, similar to that at Holywell, and an echo of the one in the contemporary Henry VII Chapel at Westminster Abbey.

Above the present chancel arch are large parts of an early 16th-century Doom painting, and the arch beneath shows striking evidence of the tracery which one filled it. The interior of the church contains notable carvings and statuary dating from the 14th century and the 16th century camberbeam wooden roof is adorned with wooden polychrome angels playing musical instruments. The church contains numerous monuments, including an elaborate sculptured memorial by Roubiliac. The brass eagle lectern was presented to the church in 1524.[12]

There are windows by the studio of Burne-Jones in the north aisle and a series of windows by Charles Eamer Kempe and C.E. Kempe and Co in the south aisle.[22] The lyrics of the Evangelical hymn "From Greenland's Icy Mountains", written by Reginald Heber, are etched on a window. The hymn was both composed and first performed at the Church in 1819.

The church contains a medieval effigy which was found buried in the churchyard at the beginning of the 19th century. This depicts a Welsh knight, bare-headed with long hair, who holds a shield emblazoned with a lion rampant and the words 'HIC JACET KENEVERIKE AP HOVEL' ('Here lies Cyneurig ap Hywel').

Just west of the tower is the grave of Elihu Yale,[12] after whom Yale University in the United States is named. The tomb was restored in 1968 by members of Yale University to mark the 250th anniversary of the benefaction.[23] It is inscribed with a self-composed epitaph beginning with the following lines:

Born in America,

in Europe bred,

In Africa travell'd and in Asia wed,

Where long he liv'd and thriv'd;

in London dead

The churchyard is entered through wrought-iron gates, completed in 1720 by the Davies Brothers of nearby Bersham, who had been responsible for the gates of Chirk Castle, perhaps the finest example of wrought-iron work in Britain,[24] and also made gates at Sandringham House, and at Leeswood Hall, near Mold in Flintshire.

In 2012, wrexham.com placed a webcam pointed at St Giles giving a live view of the church.[25] June 2012 saw a beacon being lit on top of St Giles as part of the Queen's Diamond Jubilee celebrations.

Since 2012, its interior has been re-ordered to include a re-modelling of the Chancel as St David's Chapel, and its north aisle is the home of the regimental chapel of the Royal Welch Fusiliers (now part of the Royal Welsh).

Folklore and culture

Local legend suggests that work on the church originally commenced at Brynyffynon but that each day's work was destroyed during the night and, as the day's work collapsed, a phantom voice was heard crying "Bryn y Grôg". This voice was taken to be a divine indicator that the church should instead be built on the nearby hill of that name.[12]

The church tower being blown down in 1330 was believed to have been a divine punishment arising from the town's market being held on a Sunday, which resulted in market day being moved to a Thursday.[12] The tower collapsed on St Catherine's day and a statue of St Catherine appears on the east wall of the tower, possible as a form of protection.[12]

A corbel believed to depict Thomas Stanley, 1st Earl of Derby, shows him with the ears of donkey for reasons unknown.

In May 1581, the Catholic martyr St Richard Gwyn was taken to St Giles' and carried around the font on the shoulders of six men and laid in heavy shackles in front of the pulpit. However, he 'so stirred his legs that with the noise of his irons the preacher's voice could not be heard'.[26]

There was a local myth that Oliver Cromwell fired a cannon ball at the church tower during the English Civil War.[27]

The church organ is referenced in the late-Jacobean Beaumont and Fletcher play, ‘The Pilgrim’ (1647), in which the stock Welshman declares that “Pendragon was a shentleman, marg you, Sir, and the organs at Rixum were made by relevations”.[28]

One of the most popular hymns of the 19th century, 'From Greenland's Icy Mountains' was composed by Reginald Heber on a visit to the vicarage and was first sung in public in the church in 1819.[12]

Within Acton Park in Wrexham there is a carved sandstone block which was removed from the Parish Church during the restoration programme of the early 20th century and is reputed to have magical powers so that anyone climbing onto it will be unable to get off.[11]

An unsubstantiated rumour suggests that the gravestone of Elihu Yale was stolen by the Yale University secret society, Skull and Bones, and displayed in a glass case within the society's hall known as 'The Tomb'.[29][30]

According to legend, Wrexham town centre is traversed by numerous historic underground tunnels that begin somewhere underneath St Giles Church, and generally end in pubs around the area.[31][32]

The church's tower is traditionally one of the Seven Wonders of Wales, which are commemorated in an anonymously written rhyme:

- Pistyll Rhaeadr and Wrexham steeple,

- Snowdon's mountain without its people,

- Overton yew trees, St Winefride wells,

- Llangollen bridge and Gresford bells.

The church's tower is mistakenly called a "steeple" in the rhyme.

Gallery

St Giles' Church viewed from the north-east

St Giles' Church viewed from the north-east JMW Turner, 'Wrexham, Denbighshire' (watercolour, late 18th century)

JMW Turner, 'Wrexham, Denbighshire' (watercolour, late 18th century) The tomb of Elihu Yale

The tomb of Elihu Yale 'Wrexham Tower' of Yale University, USA

'Wrexham Tower' of Yale University, USA The face of the devil in the nave roof

The face of the devil in the nave roof

References

- Simon Jenkins: Wales: Churches, Houses, Castles (Penguin 2008)

- Dodd, Arthur Herbert (1957). A History of Wrexham, Denbighshire: Published for the Wrexham Borough Council in Commemoration of the Centenary of the Incorporation of the Borough, 1857-1957. Hughes.

- Dodd, Arthur Herbert (1957). A History of Wrexham, Denbighshire: Published for the Wrexham Borough Council in Commemoration of the Centenary of the Incorporation of the Borough, 1857-1957. Hughes.

- "Visitor Information / Group Travel". stgilesparishchurchwrexham.org.uk. Retrieved 2020-08-19.

- Amin, Nathen (13 March 2014). Tudor Wales : a guide. Stroud. ISBN 978-1-4456-1773-2. OCLC 865495335.

- contact-us@wrexham.gov.uk, Wrexham County Borough Council, Guildhall, Wrexham LL11 1AY, UK. "The Open Church Network - The Parish Church of St Giles, Wrexham - WCBC". old.wrexham.gov.uk. Retrieved 2020-08-19.

- Connecticut: A Guide to Its Roads, Lore and People. US History Publishers. 1973. ISBN 978-1-60354-007-0.

- "The Courtyards | Saybrook College". saybrook.yalecollege.yale.edu. Retrieved 2020-08-20.

- "Clwyd-Powys Archaeological Trust - Projects - Longer - Historic Churches - Wrexham Churches Survey - Wrexham". www.cpat.demon.co.uk. Retrieved 2020-08-19.

- "111 – Awdl foliant i'r Abad Dafydd ab Ieuan o Lyn-y-groes". www.gutorglyn.net. Retrieved 2020-08-20.

- Williams, W. Alister (2010). The Encyclopaedia of Wrexham. Bridge Books. ISBN 978-1-84494-067-7.

- The Parish Church of St Giles, Wrexham. Wrexham: Bridge Books. 2000. ISBN 1-872424-87-2. OCLC 46394190.

- Hopkins, Edward John (1870). The Organ, its history and construction ... By E. J. H. ... Preceded by an entirely new History of the Organ, Memoirs of the most eminent Builders of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and other matters of research in connection with the subject, by E. F. Rimbault.

- Tate. "'Wrexham Church from the East', Joseph Mallord William Turner, 1794". Tate. Retrieved 2020-08-19.

- "Watercolour | | V&A Search # the Collections". V and A Collections. 2020-08-20. Retrieved 2020-08-19.

- Boswell, James (1878). The Life of Samuel Johnson, LL. D.: Including a Journal of His Tour to the Hebrides. Claxton, Remsen, & Haffelfinger.

- "Rare Bible uncovered at church". BBC News. 2015-10-07. Retrieved 2020-08-19.

- Hilling, John B. Architecture of Wales : from the first to the twenty-first century. Unwin, Simon, 1952-. Cardiff, Wales. ISBN 1-78683-284-4. OCLC 1034615762.

- Dodd, Arthur Herbert (1957). A History of Wrexham, Denbighshire: Published for the Wrexham Borough Council in Commemoration of the Centenary of the Incorporation of the Borough, 1857-1957. Hughes.

- "See Wrexham from a different viewpoint and book your St. Giles tower tour! (Plus church hosts town forum meeting)". Wrexham.com. Retrieved 2020-08-19.

- Wright, Colin. "View of Wrexham Church, North Wales". www.bl.uk. Retrieved 2020-08-19.

- History of St Giles Archived 2013-07-26 at the Wayback Machine

- Billing, Joanna (2003). The Hidden Places of Wales. Travel Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-904434-07-8.

- John Davies; Nigel Jenkins; Menna Baines (2008). The Welsh Academy encyclopaedia of Wales. University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-7083-1953-6.

- Webcam from Wrexham.com, retrieved 3 July 2016

- "SCHOOL HISTORY | St Richard Gwyn Catholic High School | Flint". SRG. Retrieved 2020-08-20.

- A History of Wrexham, Denbighshire. Dodd, A. H. (Arthur Herbert), 1891-1975., Wrexham Maelor (Wales). Borough Council. Wrexham: Published for the Wrexham Borough Council ... [by Bridge Books]. 1989. ISBN 1-872424-01-5. OCLC 59816349.CS1 maint: others (link)

- The Pilgrim. The Wild-goose-chase. The Prophetes. The Sea-voyage. The Spanish Curate: 8. Edward Moxon. 1845.

- WalesOnline (2003-11-06). "Bushes' secret society 'stole Yale gravestone'". WalesOnline. Retrieved 2020-08-20.

- Robbins, Alexandra (2000-05-01). "George W., Knight of Eulogia". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2020-08-20.

- Roberts, Craig. "What are the facts behind these Wrexham urban myths?". news.wrexham.gov.uk. Retrieved 2020-09-06.

- Morris, Lydia (2019-08-10). "First hand accounts of Wrexham's 'secret tunnels' emerge as fascination grows". North Wales Live. Retrieved 2020-09-06.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to St Giles' Church, Wrexham. |

.svg.png.webp)