Stage Irish

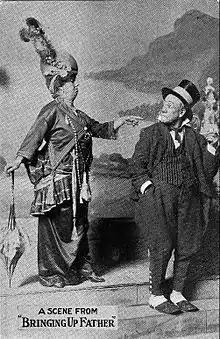

Stage Irish or Paddywhackery is a stereotyped portrayal of Irish people once common in plays.[1] The term refers to an exaggerated or caricatured portrayal of supposed Irish characteristics in speech and behaviour. The stage Irishman was generally "garrulous, boastful, unreliable, hard-drinking, belligerent (though cowardly) and chronically impecunious."[1] This caricature includes many cultural outlets, including the stage, Punch cartoons and English language cliché, such as the terms "Paddywagon" and "hooligan." Collectively, this phenomenon is called "Paddywhackery."

The early stage Irish persona arose in England in the context of the war between the Jacobites and Whig supporters of William of Orange at the end of the 17th century. Later, the stage Irish persona become more comic and less threatening. Irish writers also used the persona in a satirical way.

Early examples

The character of Teg in Robert Howard's play Committee (1662) has been claimed to be the first example of the type.[1] "There the Irish servant makes a show of false naïvety in order to outwit the Parliamentarians beleaguering his Royalist master".[1]

Captain Macmorris in Henry V by William Shakespeare is a memorable character. His line "What ish my nation?" was later appropriated by modern Irish writers, becoming a "recurrent epigraph".[1]However, Macmorris is a loyal and valiant supporter of Henry V, quite different from later, generally lower-class, stage Irishmen. Ben Johnson's The Irish Masque at Court (29 December 1613; printed 1616) is another early example of the conventions.

James Farewell's poem The Irish Hudibras (1689) was published in the wake of William's invasion of Ireland to suppress the Jacobite uprising. It is considered to be the principal origin of the stereotype. This takes the form of a parody of book VI of Virgil's Aeneid, in which Aeneas descends into the underworld. In the poem, this is replaced by Fingal in County Dublin, in which Irish costume, behaviour, and speech-patterns are parodied as if they were denizens of Hades. A companion piece, Hesperi-Neso-Grapica or A Description of the Western Isle by "W.M." was published in 1715. Pamphlets published under the title "Bog witticisms" also parodied the supposed illogicality and stupidity of the Irish.[1]

18th–20th century

Irish characters appeared in a number of plays during the 18th century. These were not all negative stereotypes. Sometimes the Irishman could be a noble, or at least sympathetic character. In others he could outwit others. Thomas Sheridan's play Captain O'Blunder is about a naive Irishman who in the end triumphs over his English rival. Lucius O'Trigger in Richard Brinsley Sheridan's The Rivals is an excessively quick-tempered individual. The character had to be rewritten because of complaints in Ireland that it was insultingly anti-Irish. All these characters were from the genteel social classes.

By the 19th century, the stage Irishman became more of a lower-class stereotype, associated with the emigrations of mid-century. Dion Boucicault's successful plays The Colleen Bawn (1860) and The Shaughraun (1874) included several Stage Irish characters.[2][3]

Patriotic inversions of the stereotype appeared in Ireland and it was commented upon by writers such as Bernard Shaw in John Bull's Other Island and by John Millington Synge in The Playboy of the Western World.[4][1] The latter play was condemned by Irish nationalists, including Sinn Féin leader Arthur Griffith, who described the play as "a vile and inhuman story told in the foulest language we have ever listened to from a public platform", and that it insulted Irish men and women.[5]

References

- stage Irishman, The Oxford Companion to Irish Literature, Oxford University Press, p.534-5.

- McFeely, Deirdre (May 2012). "Nationalism, Race and Class in The Colleen Bawn". Dion Boucicault: Irish Identity on Stage. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 13–28. doi:10.1017/cbo9781139051743.003. ISBN 9781139051743.

- Kao, Wei H. (29 December 2015). "Remaking the Stage Irishman in the New World: Dion Boucicault's The Shaughraun, Edward Harrigan's The Mulligan Guard Ball, and Sebastian Barry's White Woman Street". Contemporary Irish Theatre: Transnational Practices. Peter Lang B. doi:10.3726/978-3-0352-6574-3/6. ISBN 9783035265743.

- Innes, Christopher (2010). "Defining Irishness: Bernard Shaw and the Irish Connection on the English Stage". A Companion to Irish Literature. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 35–49. doi:10.1002/9781444328066.ch31. ISBN 9781444328066.

- Maume, Patrick (1 January 1995). "The Ancient Constitution: Arthur Griffith and His Intellectual Legacy to Sinn Féin". Irish Political Studies. 10 (1): 123–137. doi:10.1080/07907189508406541. ISSN 0790-7184.