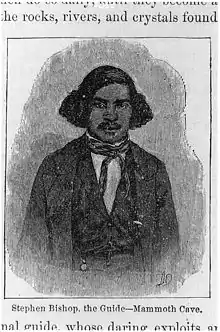

Stephen Bishop (cave explorer)

Stephen Bishop (c. 1821–1857) was a mixed race person who was enslaved (freed by manumission in the year before his death) famous for being one of the lead explorers and guides to the Mammoth Cave in the U.S. state of Kentucky.

Stephen Bishop | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | c. 1821 |

| Died | 1857 (aged 35–36) |

Bishop was introduced to Mammoth Cave in 1838 by the man who enslaved him, Franklin Gorin (1798–1877),[1] who purchased the cave from the previous owners in the spring of 1838. Gorin wrote, after Bishop's death:

I placed a guide in the cave – the celebrated and great Stephen, and he aided in making the discoveries. He was the first person who ever crossed the Bottomless Pit, and he, myself and another person whose name I have forgotten were the only persons ever at the bottom of Gorin's Dome to my knowledge.

After Stephen crossed the Bottomless Pit, we discovered all that part. of the cave now known beyond that point. Previous to those discoveries, all interest centered in what is known as the "Old Cave" . . . but now many of the points are but little known, although as Stephen was wont to say, they were 'grand, gloomy and peculiar.'

Stephen was a self-educated man. He had a fine genius, a great fund of wit and humor, some little knowledge of Latin and Greek, and much knowledge of geology, but his great talent was a knowledge of man.

Appearance and manner

Bishop's tour outfit was a chocolate-colored slouch hat, a green jacket, and striped pants. In his spare time he explored and named large areas, doubling the known map in a year. He began the naming tradition of the cave, using half-homespun American, half-classical terms (e.g., the River Styx, the Snowball Room, Little Bat Avenue, Gorin's Dome). He discovered strange blind fish, snakes, silent crickets, and the remains of cave bears along with centuries-old Indigenous gypsum workings.

In 1852, Bishop guided Nathaniel Parker Willis to Echo River. On the trip, Willis learned that, despite knowing that he would be freed in five years, Bishop intended to buy his and his wife's and son's freedom and move to Liberia, a plan which he eventually decided against.

Willis later said "he is very picturesque...part mulatto and part Indian. With more of the physiognomy of a Spaniard, with masses of black hair, curling slightly and gracefully, and his long mustache, giving quite an appearance. He is of middle size, but built for an athlete. With broad chest and shoulders, narrow hips and legs slightly bowed. Mammoth Cave is a wonder in which draws good society and Stephen shows that he is used to it."

Crossing the Bottomless Pit

After he had already explored all that had previously been discovered, Bishop began to grow bored with the cave. He knew there was more out there, but there was a limit to how far the more experienced guides would go. The farthest anyone had been in the cave was to the bottomless pit: a massive hole of darkness. None would dare venture near the pit for fear of being lost forever in its depths. Bishop was brave and his curiosity was greater than his fear. Along with a guest who was equally as curious and daring as Bishop, the two men journeyed to the pit. With the help of a cedar sapling,[2] they laid it across the gaping mouth of the pit and slowly ventured across. What the two men discovered opened up a whole new part of the cave. A short way further from the pit Bishop discovered a river. This was the first body of water that had ever been encountered in the cave. As he explored the river he found eyeless fish: something that no one had ever heard about at this time. This brought scientists to the cave to study the new creature.[3] Some of the most popular areas of the cave were both discovered and named by Bishop after crossing the bottomless pit.

Bishop's 1842 map of Mammoth Cave

In 1839, Dr. John Croghan of Louisville bought the Mammoth Cave Estate, including Bishop and other people from their previous enslaver, Franklin Gorin. Croghan briefly ran an ill-fated tuberculosis hospital in the cave, the vapors of which he believed would cure his patients. A widespread epidemic of the period, tuberculosis would ultimately claim the lives of both Bishop and Croghan.

In 1842, Bishop was sent to Croghan's estate (Locust Grove, in Louisville) for two weeks to draw a map, from memory, of the cave system (see Mammoth Cave). The map was published in 1844 by Morton and Griswold as a pull-out insert in Alexander Clark Bullitt's Rambles in Mammoth Cave in the Year 1844 by a Visiter [sic] (Morton and Griswold, 1845.) Unusually for an enslaved person, Bishop was given full credit for his work. The Bishop map remained in use for over forty years.

Bishop's map showed some 16 km of cave passages, half of which were discovered by him. While the map does not represent a modern accurate instrumental survey, he took some pains to indicate relative passage dimension and length, with cross shading to show water (as modern cave cartographers do.) The topology, if not the scale and orientation, of the map is accurate, that is, the indications of junction layouts correspond to reality in a way that some later celebrated maps do not. Beyond this, the Bishop map is the first to truly suggest, at a glance, the majestic scale of Mammoth Cave, especially its extraordinary degree of connectivity. In 160 years, Bishop's map has not lost the ability to inspire interest in both its subject and its source.

In 1972, when modern explorers discovered a connection between the Flint Ridge Cave system to the northeast and Mammoth Cave, they were astonished to discover that the Mammoth Cave end of the connection was actually indicated as a passage lead on Bishop's map. (It is seen as a long thin line branching off from the eastern end of the Echo River complex.) The construction in 1905 of a dam on the Green River in the interim caused the passage to be flooded (and therefore inaccessibly hidden by murky water) most of the time after the dam's completion, and the passage was rediscovered backwards, from its remote end, by cavers entering the Flint Ridge Cave System. Although he never knew its significance, Bishop had unwittingly shown the key to connecting two major components of the longest cave in the world, 130 years before the connection was made.

Family

During his time at Croghan's estate Bishop met Charlotte Brown, an enslaved house worker for Croghan's family. They married in approximately 1843 at Croghan's estate, Locust Grove, located in Jefferson County. Charlotte gave birth to their son Thomas Bishop about a year later in 1844.[4] Not much is known about Bishop's son Thomas. Bishop's nephew Eddie followed in his uncle's footsteps and became a guide of Mammoth Cave also.[5]

Freedom and death

Bishop was freed in 1856, seven years after the death of his enslaver, in accordance with Dr. Croghan's will. While Bishop had talked of buying his wife and son's freedom and traveling to Liberia, he never went. Shortly after his family's freedom Bishop bought a small plot of land for his family instead. Bishop died on June 15, 1857. It is unknown if his desire to go to Liberia was sincere or was a way to convey an impression of personal ambition in a non-threatening manner to white visitors.

Bishop's wife, the former Charlotte Brown, was reunited with her brother Jim Brown prior to her death in 1897. As a widow, she became the wife of cave guide Nick Bransford, who died in 1894.

Bishop was buried on the south hill above the cave in what became known as "The Old Guides' Cemetery." According to Mammoth Cave Historian Harold Meloy ("Stephen Bishop: The Man and the Legend", in Caves, Cavers, and Caving, Bruce Sloane, Editor, 1977, pp. 290–91), James Ross Mellon, president of the City Deposit Bank, Pittsburgh, PA, visited the cave for one week in November 1878. He heard charming stories of Bishop, and he met Charlotte, who then managed the hotel dining room. She led him to Stephen's gravesite, "which had only a cedar tree to mark it." Mellon promised to have a headstone carved for Stephen's grave. Three years after Mellon returned home to Pittsburgh he remembered his promise to Charlotte. He arranged for a monument carver to prepare the stone. In 1881 a stonemason used a second-hand tombstone that a Civil War soldier's family had not paid for, he chiseled off the original name and placed an inscription that read,

STEPHEN BISHOP, FIRST GUIDE & EXPLORER OF THE MAMMOTH CAVE. DIED JUNE 15, 1859 IN HIS 37 YEAR.

The stone was shipped to the cave and installed on Bishop's grave. According to Harold Meloy, "The error in the date of death [1859 vs. 1857] detracted nothing from the legend now reinforced by a permanent record in stone."

In literature

- In 2009, author and cave explorer Roger W. Brucker published Grand, Gloomy, and Peculiar: Stephen Bishop at Mammoth Cave, a historical novel written from the point of view of Bishop's wife, Charlotte Brown.

- In 2004, author Elizabeth Mitchell published Journey to the Bottomless Pit: The Story of Stephen Bishop & Mammoth Cave, a historical novel written from the point of view of Bishop.

- Bishop is a primary character in Alex Irvine's 2002 novel A Scattering of Jades.

References

- "USGenweb Archives: Franklin Gorin, 1877, Barren County".

- "Saxby's magazine [1899, January-June]". digital.cincinnatilibrary.org. Retrieved 2019-07-25.

- Judith, Boogaart. "Stephen Bishop: Cave Explorer". Highlights Kids.

- Frank, Edward Forrest. "Charlotte Bishop 1860". Black Guides of Mammoth Cave. Retrieved 2015-11-29.

- Johnston, Frances Benjamin.Mammoth Cave by Flash-light. Washington, D.C.: Gibson Bros., Printers, 1893.13. Explore UK. Web. 11 November 2015

External links

- Stephen Bishop, Cave Guide Single page PDF from the United States National Park Service.

- Teaching resource from US National Park Service (pdf)

- BlackHistory.com article

- Coax.net article by Henry Robert Burke. Contains two (possibly three) false claims: that Stephen Bishop discovered Mammoth Cave (false), that Bishop discovered a pre-Columbian mummy (false), and that Bishop used the cave to hide slaves escaping on the Underground Railroad (veracity unknown, but dubious.)

- Peter West, "Trying the Dark: Mammoth Cave and the Racial Imagination, 1839–1869", Southern Spaces, 9 February 2010