Stephen Girard

Stephen Girard (May 20, 1750 – December 26, 1831; born Étienne Girard, was a naturalized American philanthropist, banker, and slave owner of French origin.[2][3] He personally saved the U.S. government from financial collapse during the War of 1812, and became one of the wealthiest people in America, estimated to have been the fourth richest American of all time, based on the ratio of his fortune to contemporary GDP.[4] Childless, he devoted much of his fortune to philanthropy, particularly the education and welfare of orphans. His legacy is still felt in his adopted home of Philadelphia.[5]

Stephen Girard | |

|---|---|

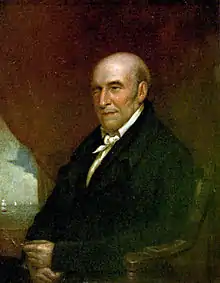

Girard in 1831 (oil portrait by James Lambdin) | |

| Born | May 20, 1750 |

| Died | December 26, 1831 (aged 81) |

| Net worth | USD $7.5 million at the time of his death (approximately 1/150th of US GNP)[1] |

| Signature | |

| |

Early life

Girard was born in Bordeaux, France on 21 May 1750 the son of a common sailor.[6]

He lost the sight of his right eye at the age of eight and had little education. He travelled to New York as a cabin boy in 1760 and stayed there, working in the coastal trader system along the east coast and as far south as the Caribbean.[7] He was licensed as a captain in 1773, visited California in 1774, and thence with the assistance of a New York merchant began to trade to and from New Orleans and Port au Prince. In May 1776, he was driven into the port of Philadelphia by a British fleet and settled there running a grocery and liquor shop.[8]

By 1790, he had a fortune of £6000 plus a small fleet of trading vessels. In 1791 his ships at St Domingo in Haiti were involved in trying to salvage goods for European slave owners during the slave revolt. It was claimed that he was left with £10.000 of goods stowed on his ships, the owners of which were massacred, He said he could not trace any owners for the goods and so they were conveniently added to his own possessions.[9]

Marriage

In 1776, Girard met Mary Lum, a Philadelphia native nine years his junior. They married soon afterwards, and Girard purchased a home at 211 Mill Street in Mount Holly Township, New Jersey.[10] She was the daughter of John Lum, a shipbuilder who died three months before the marriage. In 1778 Girard became a resident of Pennsylvania. By 1785 Mary had begun succumbing to sudden, erratic emotional outbursts. Mental instability and violent rages ensued, leading to a diagnosis of incurable mental instability. Though Girard was initially devastated, by 1787 he took a mistress, Sally Bickham. In August 1790 Girard committed his wife to the Pennsylvania Hospital (today part of the University of Pennsylvania) as an incurable lunatic. He provided her every luxury for comfort, she gave birth to a girl whose sire is not entirely certain. The child, baptized with the name Mary, died a few months later while under the care of Mrs. John Hatcher, who had been hired by Girard as a nurse. Girard spent the remainder of his life with mistresses.[10]

Yellow fever

In 1793, there was an outbreak of yellow fever in Philadelphia. Although many other well-to-do citizens chose to leave the city, Girard stayed to care for the sick and dying. He supervised the conversion of a mansion outside the city limits into a hospital and recruited volunteers to nurse victims, and personally cared for patients. For his efforts, Girard was feted as a hero after the outbreak subsided.[11] Again during the yellow fever epidemic of 1797-1798 he took the lead in relieving the poor and caring for the sick.[8]

Girard Bank

After the charter for the First Bank of the United States expired in 1811, Girard purchased most of its stock and its facilities on South Third Street in Philadelphia, and reestablished it under his direct personal ownership. He hired George Simpson, the cashier of the First Bank, as cashier of the new bank, and with seven other employees, opened for business on May 18, 1812. He allowed the Trustees of the First Bank of the United States to use some offices and space in the vaults to continue the process of winding down the affairs of the closed bank at a very nominal rent.[12] Although Pennsylvania law prohibited an association of individuals from banking without a charter, it made no such prohibition on a single individual doing so.[13] Philadelphia banks balked at accepting the notes that Girard issued on his personal credit and lobbied the state to force him to incorporate, without success.[14]

Girard's Bank was a principal source of government credit during the War of 1812 an outstanding $1 million.

Towards the end of the war, when the financial credit of the U.S. government was at its lowest, Girard placed nearly all of his resources at the disposal of the government and underwrote up to 95 percent of the war loan issue, which enabled the United States to carry on the war. After the war, he became a large stockholder in and one of the directors of the Second Bank of the United States. Girard's bank became the Girard Trust Company, and later Girard Bank. It merged with Mellon Bank in 1983, and was largely sold to Citizens Bank two decades later. Its monumental headquarters building still stands at Broad and Chestnut Streets in Philadelphia.

Death, will and legacy

.jpg.webp)

On December 22, 1830, Stephen Girard was seriously injured while crossing the street near Second and Market Streets in Philadelphia. He was knocked down by a horse and wagon, and one of its wheels ran over the left side of his face, lacerating his cheek and ear, as well as damaging his good (left) eye. Despite his age (81), he got up unassisted and returned to his nearby home, where a doctor dressed his wound. He threw himself back into his banking business, although he remained out of sight for two months. Nevertheless, he never fully recovered and he died on December 26, 1831, coincidentally the Feast of St. Etienne--St. Stephen's Day in the Western Church. He was buried in the vault he built for his nephew in the Holy Trinity Catholic cemetery, then at Sixth and Spruce Streets. Twenty years later, his remains were re-interred in the Founder's Hall vestibule at Girard College behind a statue by Nicholas Gevelot, a French sculptor living in Philadelphia.[5]

At the time of his death, Girard was the wealthiest man in America.[15] Michael Klepper and Robert Gunther, in their book The Wealthy 100,[16] posit that, with adjustment for inflation, Girard was the fourth-wealthiest American of all time as of 1996, behind John D. Rockefeller, Cornelius Vanderbilt and John Jacob Astor. He left $1,800,000, equal to $43,216,875 today.

He was an atheist all the way up to his death, and he included his views on religion in his last testament.[17]

Girard's will[18] was contested by his family in France but was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in a landmark case, Vidal et al. vs Girard's Executors, 43 U.S. 127 (1844).[19]

He bequeathed nearly his entire fortune to charitable[20] and municipal institutions of Philadelphia and New Orleans, including an endowment of $400,000 for establishing a boarding school for "poor, male, white orphans" in Philadelphia, primarily those who were the children of coal miners, which opened as the Girard College in 1848.

Girard also made a bequest of $10,000 to the public schools of Philadelphia, with the income from its investment to be used for the purchase of books for the school libraries, and a bequest for the establishment of funds to procure medals for deserving pupils.[21]

.jpg.webp)

A number of places are named after Stephen Girard.

- Girard Avenue is a major east–west thoroughfare of North Philadelphia and West Philadelphia and the location of Girard College.

- The neighborhood now known as Girard Estate is part of what was a successful farm that he established in the late 1700s, and includes the Stephen Girard Park where his mansion still stands.

- Girard Fountain Park is in the Old City neighborhood of Philadelphia, in which a sculpture of Benjamin Franklin is displayed.

- The borough of Girardville, Schuylkill County, is located roughly 110 miles northwest of Philadelphia, bordered by many acres of land still connected to the Girard Estate.

- Stephen Girard Avenue is located in the Gentilly area of New Orleans.

- Girard, Pennsylvania is located in Erie County, Pennsylvania, roughly 450 miles northwest of Philadelphia; named for him in 1832.

- The community of Girard, Louisiana, is in Richland Parish, where Girard financed and oversaw the startup of a plantation managed by his friend and agent, Henry Bry, in 1821.[22]

See also

- Stephen Simpson (writer), former employee at Girard's bank and author of book Biography of Stephen Girard, with His Will Affixed (1832), very critical of Girard.

- List of richest Americans in history

- List of wealthiest historical figures

- War of 1812

References

- Klepper, Michael; Gunther, Michael (1996), The Wealthy 100: From Benjamin Franklin to Bill Gates—A Ranking of the Richest Americans, Past and Present, Secaucus, New Jersey: Carol Publishing Group, p. xi, ISBN 978-0-8065-1800-8, OCLC 33818143

- Rey, Terry (2017). The Priest and the Prophetess: Abbé Ouvière, Romaine Rivière, and the Revolutionary Atlantic World. Oxford University Press. p. 11. ISBN 9780190625849.

Philadelphia’s wealthiest man and leading philanthropist, Stephen Girard, was a Frenchman whose fortune was made on the backs of slaves whom he owned in Saint-Domingue, for example, while French jurist Médéric Louis Élie Moreau de Saint-Méry’s Description topographique, physique, civile, politique et historique de la partie française de Saint-Domingue, our most important single source of information about the colony, was first published in Philadelphia, the city in which he then resided, in 1797–1798.

- Ruth E. Hodge. "MG-252. STEPHEN GIRARD COLLECTION, 1786-1856 (Bulk 1828-1842)". Guide to African American Resources at the Pennsylvania State Archives. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

The will contains several references to African Americans, including mention of his "black woman" Hannah, to whom he gave an annual sum of two hundred dollars for the remainder of her life. He also specified that part of his real and personal estate near Washita, Louisiana, including thirty slaves, be given to his friend Judge Henry Bree.

- In Fortune Magazine: "richest Americans: Archived 2009-09-19 at the Wayback Machine, with an estimated wealth at death of $7,500,000 Girard's Wealth/GDP ratio equalled 1/150.

- Wildes, 1943.

- Robert Chambers' Book of Days vol 2. p.767

- Robert Chambers Book of Days vol.2 p.766

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Robert Chambers Book of Days vol2. p.767

- DiMeo, Mike. "Stephen Girard". www.ushistory.org. Independence Hall Association. Retrieved 2016-08-14.

- Wilson, George (1995). Stephen Girard. Conshohocken: Combined Books. pp. 121–133. ISBN 0-938289-56-X.

- Wilson, George (1995). Stephen Girard. Conshohocken: Combined Books. p. 249. ISBN 0-938289-56-X.

- Wilson, George (1995). Stephen Girard. Conshohocken: Combined Books. pp. 249–250. ISBN 0-938289-56-X.

- Herrick, Cheesman Abiah (1923). Stephen Girard, Founder.

- Wilson, George (1995). Stephen Girard. Conshohocken: Combined Books. pp. 329–333. ISBN 0-938289-56-X.

- Michael, Klepper; Gunther, Robert (1996). The Wealthy 100: From Benjamin Franklin to Bill Gates - A Ranking of the Richest Americans, Past and Present. Citadel Press. ISBN 978-0806518008. Retrieved 12 August 2019.

- Gray, Carole (Spring 1999). "The Atheist Who Saved The United States (...and the thanks he got for it)". The American Atheist. 37 (2): 34–44. Archived from the original on 2008-06-04.

One of his longtime employees, whose father had also worked for Stephen, said of him, "on the subject of religion, his opinions were atheistic. Let not the reader start, to find himself in company with one, who utterly disbelieved in all modes of a future existence, and who rejected with inward contempt every formulary of religion, as idle, vain, and unmeaning. Yet such were the convictions of Girard, held to his dying hour, and perpetuated in his last testament as a legacy to future generations .... He was known to be totally irreligious; and to attempt to conceal what is notorious, would be to suppress one of the most extraordinary features of his character."

- DiFilippo, Thomas J. "The Will, No Longer Sacred". Stephen Girard, The Man, His College and Estate. Joe Ross. Retrieved 2016-08-14.

- "Vidal v. Girard's Executors". Justia. U.S. Supreme Court. Retrieved 2016-08-14.

- Klem, Monica. "Stephen Girard | The Philanthropy Hall of Fame | The Philanthropy Roundtable". Philanthropy Roundtable. Retrieved 2016-08-14.

- The Public Schools of Philadelphia: Historical, Biographical, Statistical by John Trevor Custis, Burk & McFetridge Co. Publisher, 1897, Pg. 16

- "25 Apr 1954, Page 26 - Monroe Morning World at Newspapers.com". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2018-08-18.

Further reading

- Adams, Donald. Finance and Enterprise in Early America: A Study of Stephen Girard’s Bank, 1812–1831 (1978)

- McMaster, John Bach. The Life and Times of Stephen Girard, Mariner and Merchant (2 vol. 1918) online

- Wildes, Harry E. Lonely Midas: The Story of Stephen Girard (1943).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stephen Girard. |

| Wikisource has the text of an 1879 American Cyclopædia article about Stephen Girard. |

- Founder's Hall - Stephen Girard

- Stephen Girard at Find a Grave

- Country Farmhouse and Outbuildings of Mr. Stephen Girard, Philadelphia, May 1891 by D.J. Kennedy, Historical Society of Philadelphia Archived at the Wayback Machine (archived 2016-03-04)

- The French assault on American Shipping 1793-1813

- The Polly ship of GIRARD

- The Helvetius ship of GIRARD

- The Helvetius ship of GIRARD

- The Montesquieu of GIRARD

- The North America ship of GIRARD

- The North America ship of GIRARD

- The Rousseau ship of GIRARD