Strongly regular graph

In graph theory, a strongly regular graph is defined as follows. Let G = (V, E) be a regular graph with v vertices and degree k. G is said to be strongly regular if there are also integers λ and μ such that:

- Every two adjacent vertices have λ common neighbours.

- Every two non-adjacent vertices have μ common neighbours.

A graph of this kind is sometimes said to be an srg(v, k, λ, μ). Strongly regular graphs were introduced by Raj Chandra Bose in 1963.[1]

Some authors exclude graphs which satisfy the definition trivially, namely those graphs which are the disjoint union of one or more equal-sized complete graphs,[2][3] and their complements, the complete multipartite graphs with equal-sized independent sets.

The complement of an srg(v, k, λ, μ) is also strongly regular. It is an srg(v, v−k−1, v−2−2k+μ, v−2k+λ).

A strongly regular graph is a distance-regular graph with diameter 2 whenever μ is non-zero. It is a locally linear graph whenever λ is one.

Properties

Relationship between Parameters

The four parameters in an srg(v, k, λ, μ) are not independent and must obey the following relation:

The above relation can be derived very easily through a counting argument as follows:

- Imagine the vertices of the graph to lie in three levels. Pick any vertex as the root, in Level 0. Then its k neighbors lie in Level 1, and all other vertices lie in Level 2.

- Vertices in Level 1 are directly connected to the root, hence they must have λ other neighbors in common with the root, and these common neighbors must also be in Level 1. Since each vertex has degree k, there are edges remaining for each Level 1 node to connect to nodes in Level 2. Therefore, there are edges between Level 1 and Level 2.

- Vertices in Level 2 are not directly connected to the root, hence they must have μ common neighbors with the root, and these common neighbors must all be in Level 1. There are vertices in Level 2, and each is connected to μ nodes in Level 1. Therefore the number of edges between Level 1 and Level 2 is .

- Equating the two expressions for the edges between Level 1 and Level 2, the relation follows.

Adjacency Matrix

Let I denote the identity matrix and let J denote the matrix of ones, both matrices of order v. The adjacency matrix A of a strongly regular graph satisfies two equations. First:

which is a trivial restatement of the regularity requirement. This shows that k is an eigenvalue of the adjacency matrix with the all-ones eigenvector. Second is a quadratic equation,

which expresses strong regularity. The ij-th element of the left hand side gives the number of two-step paths from i to j. The first term of the RHS gives the number of self-paths from i to i, namely k edges out and back in. The second term gives the number of two-step paths when i and j are directly connected. The third term gives the corresponding value when i and j are not connected. Since the three cases are mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive, the simple additive equality follows.

Conversely, a graph whose adjacency matrix satisfies both of the above conditions and which is not a complete or null graph is a strongly regular graph.[4]

Eigenvalues

The adjacency matrix of the graph has exactly three eigenvalues:

- k, whose multiplicity is 1 (as seen above)

- whose multiplicity is

- whose multiplicity is

As the multiplicities must be integers, their expressions provide further constraints on the values of v, k, μ, and λ, related to the so-called Krein conditions.

Strongly regular graphs for which are called conference graphs because of their connection with symmetric conference matrices. Their parameters reduce to

Strongly regular graphs for which have integer eigenvalues with unequal multiplicities.

Conversely, a connected regular graph with only three eigenvalues is strongly regular.[5]

Examples

- The cycle of length 5 is an srg(5, 2, 0, 1).

- The Petersen graph is an srg(10, 3, 0, 1).

- The Clebsch graph is an srg(16, 5, 0, 2).

- The Shrikhande graph is an srg(16, 6, 2, 2) which is not a distance-transitive graph.

- The n × n square rook's graph, i.e., the line graph of a balanced complete bipartite graph Kn,n, is an srg(n2, 2n − 2, n − 2, 2). The parameters for n=4 coincide with those of the Shrikhande graph, but the two graphs are not isomorphic.

- The line graph of a complete graph Kn is an srg().

- The Chang graphs are srg(28, 12, 6, 4), the same as the line graph of K8, but these four graphs are not isomorphic.

- The line graph of a generalized quadrangle GQ(2, 4) is an srg(27, 10, 1, 5). In fact every generalized quadrangle of order (s, t) gives a strongly regular graph in this way: to wit, an srg((s+1)(st+1), s(t+1), s-1, t+1).

- The Schläfli graph is an srg(27, 16, 10, 8).[6]

- The Hoffman–Singleton graph is an srg(50, 7, 0, 1).

- The Sims-Gewirtz graph is an (56, 10, 0, 2).

- The M22 graph aka Mesner graph is an srg(77, 16, 0, 4).

- The Brouwer–Haemers graph is an srg(81, 20, 1, 6).

- The Higman–Sims graph is an srg(100, 22, 0, 6).

- The Local McLaughlin graph is an srg(162, 56, 10, 24).

- The Cameron graph is an srg(231, 30, 9, 3).

- The Berlekamp–van Lint–Seidel graph is an srg(243, 22, 1, 2).

- The McLaughlin graph is an srg(275, 112, 30, 56).

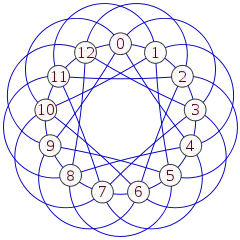

- The Paley graph of order q is an srg(q, (q − 1)/2, (q − 5)/4, (q − 1)/4). The smallest Paley graph, with q=5, is the 5-cycle (above).

- self-complementary arc-transitive graphs are strongly regular.

A strongly regular graph is called primitive if both the graph and its complement are connected. All the above graphs are primitive, as otherwise μ=0 or λ=k.

Conway's 99-graph problem asks for the construction of an srg(99, 14, 1, 2). It is unknown whether a graph with these parameters exists, and John Horton Conway has offered a $1000 prize for the solution to this problem.[7]

Triangle-free graphs, Moore graphs, and geodetic graphs

The strongly regular graphs with λ = 0 are triangle free. Apart from the complete graphs on less than 3 vertices and all complete bipartite graphs the seven listed above (pentagon, Petersen, Clebsch, Hoffman-Singleton, Gewirtz, Mesner-M22, and Higman-Sims) are the only known ones. Strongly regular graphs with λ = 0 and μ = 1 are Moore graphs with girth 5. Again the three graphs given above (pentagon, Petersen, and Hoffman-Singleton), with parameters (5, 2, 0, 1), (10, 3, 0, 1) and (50, 7, 0, 1), are the only known ones. The only other possible set of parameters yielding a Moore graph is (3250, 57, 0, 1); it is unknown if such a graph exists, and if so, whether or not it is unique.[8]

More generally, every strongly regular graph with is a geodetic graph, a graph in which every two vertices have a unique unweighted shortest path.[9] The only known strongly regular graphs with are the Moore graphs. It is not possible for such a graph to have , but other combinations of parameters such as (400, 21, 2, 1) have not yet been ruled out. Despite ongoing research on the properties that a strongly regular graph with would have,[10][11] it is not known whether any more exist or even whether their number is finite.[9]

Notes

- https://projecteuclid.org/euclid.pjm/1103035734, R. C. Bose, Strongly regular graphs, partial geometries and partially balanced designs, Pacific J. Math 13 (1963) 389–419. (p. 122)

- Brouwer, Andries E; Haemers, Willem H. Spectra of Graphs. p. 101 Archived 2012-03-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Godsil, Chris; Royle, Gordon. Algebraic Graph Theory. Springer-Verlag New York, 2001, p. 218.

- Cameron, P.J.; van Lint, J.H. (1991), Designs, Graphs, Codes and their Links, London Mathematical Society Student Texts 22, Cambridge University Press, p. 37, ISBN 978-0-521-42385-4

- Godsil, Chris; Royle, Gordon. Algebraic Graph Theory. Springer-Verlag, New York, 2001, Lemma 10.2.1.

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Schläfli graph", MathWorld

- Conway, John H., Five $1,000 Problems (Update 2017) (PDF), Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences, retrieved 2019-02-12

- Dalfó, C. (2019), "A survey on the missing Moore graph", Linear Algebra and its Applications, 569: 1–14, doi:10.1016/j.laa.2018.12.035, hdl:2117/127212, MR 3901732

- Blokhuis, A.; Brouwer, A. E. (1988), "Geodetic graphs of diameter two", Geometriae Dedicata, 25 (1–3): 527–533, doi:10.1007/BF00191941, MR 0925851

- Deutsch, J.; Fisher, P. H. (2001), "On strongly regular graphs with ", European Journal of Combinatorics, 22 (3): 303–306, doi:10.1006/eujc.2000.0472, MR 1822718

- Belousov, I. N.; Makhnev, A. A. (2006), "On strongly regular graphs with and their automorphisms", Doklady Akademii Nauk, 410 (2): 151–155, MR 2455371

References

- A.E. Brouwer, A.M. Cohen, and A. Neumaier (1989), Distance Regular Graphs. Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 3-540-50619-5, ISBN 0-387-50619-5

- Chris Godsil and Gordon Royle (2004), Algebraic Graph Theory. New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-95241-1