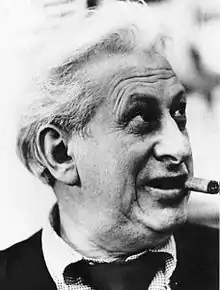

Studs Terkel

Louis "Studs" Terkel (May 16, 1912 – October 31, 2008)[1] was an American author, historian, actor, and broadcaster. He received the Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction in 1985 for The Good War and is best remembered for his oral histories of common Americans, and for hosting a long-running radio show in Chicago.

Studs Terkel | |

|---|---|

Terkel in 1979 | |

| Born | Louis Terkel May 16, 1912 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died | October 31, 2008 (aged 96) Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Pen name | Studs Terkel |

| Occupation | Author, historian, radio personality, actor |

| Alma mater | University of Chicago (Ph.B., 1932; J.D., 1934) |

| Notable awards | Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction, 1985 |

| Spouse | Ida Goldberg (1939–1999) |

| Children | 1 |

| Website | |

| studsterkel | |

Early life

Terkel was born to Russian Jewish immigrants, Samuel Terkel, a tailor, and Anna (Annie) Finkel, a seamstress, in New York City.[2] At the age of eight, he moved with his family to Chicago, Illinois, where he spent most of his life. He had two brothers, Ben (1907–1965) and Meyer (1905–1958). He attended McKinley High School.[3]

From 1926 to 1936, his parents ran a rooming house that also served as a meeting place for people from all walks of life. Terkel credited his understanding of humanity and social interaction to the tenants and visitors who gathered in the lobby there, and the people who congregated in nearby Bughouse Square.

In 1939, he married Ida Goldberg (1912–1999), and the couple had one son. Although he received his undergraduate degree in 1932, and a J.D. degree from the University of Chicago in 1934 (and was admitted to the Illinois Bar the following year), he decided instead of practicing law; he wanted to be a concierge at a hotel, and he soon joined a theater group.[4]

Career

A political leftist, Terkel joined the Works Progress Administration's Federal Writers' Project, working in radio, doing work that varied from voicing soap opera productions and announcing news and sports, to presenting shows of recorded music and writing radio scripts and advertisements. His well-known radio program, titled The Studs Terkel Program, aired on 98.7 WFMT Chicago between 1952 and 1997.[5] The one-hour program was broadcast each weekday during those forty-five years. On this program, he interviewed guests as diverse as Martin Luther King Jr., Leonard Bernstein, Mort Sahl, Bob Dylan, Alexander Frey, Dorothy Parker, Tennessee Williams, Jean Shepherd, Frank Zappa, and Big Bill Broonzy.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Terkel was also the central character of Studs' Place, an unscripted television drama about the owner of a greasy-spoon diner in Chicago through which many famous people and interesting characters passed. This show, along with Marlin Perkins's Zoo Parade, Garroway at Large and the children's show Kukla, Fran, and Ollie, are widely considered canonical examples of the Chicago School of Television.

Terkel published his first book, Giants of Jazz, in 1956. He followed it in 1967 with his first collection of oral histories, Division Street America with 70 people talking about the effect on the human spirit of living in an American metropolis.[6][7][8]

He also served as a distinguished scholar-in-residence at the Chicago History Museum. He appeared in the film Eight Men Out, based on the Black Sox Scandal, in which he played newspaper reporter Hugh Fullerton, who tries to uncover the White Sox players' plans to throw the 1919 World Series. Terkel found it particularly amusing to play this role, as he was a big fan of the Chicago White Sox (as well as a vocal critic of major league baseball during the 1994 baseball strike), and gave a moving congratulatory speech to the White Sox organization after their 2005 World Series championship during a television interview.

Terkel received his nickname while he was acting in a play with another person named Louis. To keep the two straight, the director of the production gave Terkel the nickname Studs after the fictional character about whom Terkel was reading at the time—Studs Lonigan, of James T. Farrell's trilogy.

Terkel was acclaimed for his efforts to preserve American oral history. His 1985 book "The Good War": An Oral History of World War Two, which detailed ordinary peoples' accounts of the country's involvement in World War II, won the Pulitzer Prize. For Hard Times: An Oral History of the Great Depression, Terkel assembled recollections of the Great Depression that spanned the socioeconomic spectrum, from Okies, through prison inmates, to the wealthy. His 1974 book, Working, in which (as reflected by its subtitle) People Talk About What They Do All Day and How They Feel About What They Do, also was highly acclaimed. Working was made into a short-lived Broadway show of the same title in 1978 and was telecast on PBS in 1982. In 1995, he received the Chicago History Museum "Making History Award" for Distinction in Journalism and Communications. In 1997, Terkel was elected a member of The American Academy of Arts and Letters. Two years later, he received the George Polk Career Award in 1999.

Later life

In 2004, Terkel received the Elijah Parish Lovejoy Award as well as an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from Colby College. In August 2005, Terkel underwent successful open-heart surgery. At the age of ninety-three, he was one of the oldest people to undergo this form of surgery and doctors reported his recovery to be remarkable for someone of that advanced age. Terkel smoked two cigars a day until 2004.

On May 22, 2006, Terkel, along with other plaintiffs, including Quentin Young, filed a suit in federal district court against AT&T Inc., to stop the telecommunications carrier from giving customer telephone records to the National Security Agency without a court order.[9]

Having been blacklisted from working in television during the McCarthy era, I know the harm of government using private corporations to intrude into the lives of innocent Americans. When the government uses the telephone companies to create massive databases of all our phone calls it has gone too far.

The lawsuit was dismissed by Judge Matthew F. Kennelly on July 26, 2006. Judge Kennelly cited a "state secrets privilege" designed to protect national security from being harmed by lawsuits.[10]

In an interview in The Guardian celebrating his 95th birthday, Terkel discussed his own "diverse and idiosyncratic taste in music, from Bob Dylan to Alexander Frey, Louis Armstrong to Woody Guthrie".[11]

Terkel published a new personal memoir entitled Touch and Go in fall 2007.[12]

Terkel was a self-described agnostic,[13] which he jokingly defined as "a cowardly atheist" during a 2004 interview with Krista Tippett on American Public Media's Speaking of Faith.[14]

One of his last interviews was for the documentary Soul of a People on Smithsonian Channel. He spoke about his participation in the Works Progress Administration.

At his last public appearance, in 2007, Terkel said he was "still in touch—but ready to go".[15] He gave one of his last interviews on the BBC Hardtalk program on February 4, 2008.[16] He spoke of the imminent election of Barack Obama as President of the United States, and offered him some advice, in October 2008.[17]

Terkel died in his Chicago home on Friday, October 31, 2008, at the age of ninety-six. He had been suffering ever since a fall in his home earlier that month.[18]

Legacy and audio recordings

| External audio | |

|---|---|

In 1998, Terkel and WFMT, the radio station which broadcast Terkel's long-running program, donated approximately 7,000 tape recordings of Terkel's interviews and broadcasts to the Chicago History Museum.

In 2010, the Museum and the Library of Congress announced a multi-year joint collaboration to digitally preserve and make available at both institutions these recordings, which the Library of Congress called, "a remarkably rich history of the ideas and perspectives of both common and influential people living in the second half of the 20th century." "For Studs, there was not a voice that should not be heard, a story that could not be told," said Gary T. Johnson, Museum president. "He believed that everyone had the right to be heard and had something important to say. He was there to listen, to chronicle, and to make sure their stories are remembered."[22]

In 2014 WFMT and the Chicago History Museum announced the creation of the website, Studsterkel.org (see studsterkel.wfmt.com), which will house the entire archive of Studs Terkel interviews.

On Sept. 5, 2019, podcast The Radio Diaries, produced by Radiotopia on PRX, released an episode called "The Working Tapes of Studs Terkel." In it, Terkel's taped interviews with working people are played and examined.[23]

Awards and honors

In 1982, Terkel was awarded an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters from the University of Illinois at Chicago.[24]

In 1985, Terkel received the Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction for his book The Good War.

President Clinton awarded Terkel the National Humanities Medal in 1997.[25]

The National Book Foundation awarded Terkel the 1997 Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters.[26]

In 2001, Terkel was inducted into the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame as a Friend of the Community.[27]

In 2004, Terkel was inducted as a Laureate of The Lincoln Academy of Illinois and awarded the Order of Lincoln (the State's highest honor) by the Governor of Illinois in the area of Communications.[28]

In 2006, Terkel received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Dayton Literary Peace Prize, the first and only annual U.S. literary award recognizing the power of the written word to promote peace.[29][30]

In 2010, Terkel was inducted into the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame.[31]

Terkel was a recipient of a George Polk Career Award and the National Book Critics Circle 2003 Ivan Sandrof Lifetime Achievement Award.[32]

Terkel, despite not being black, was inducted into the Hall of Fame of Black Writers at the insistence of Haki Madhubuti.[33]

Selected works

- Giants of Jazz (1957). ISBN 1-56584-769-5

- Division Street: America (1967) ISBN 0-394-42267-8

- Hard Times: An Oral History of the Great Depression (1970) ISBN 0-394-42774-2

- Working: People Talk About What They Do All Day and How They Feel About What They Do (1974). ISBN 0394478843

- Talking to Myself: A Memoir of My Times (1973, reprinted 1977) ISBN 0-394-41102-1

- American Dreams: Lost and Found (1983)

- The Good War (1984) ISBN 0-394-53103-5

- Chicago (1986) ISBN 5-551-54568-7

- The Great Divide: Second Thoughts on the American Dream (1988) ISBN 0-394-57053-7

- Race: What Blacks and Whites Think and Feel About the American Obsession (1992). ISBN 978-1-56584-000-3

- Coming of Age: The Story of Our Century by Those Who've Lived It (1995) ISBN 1-56584-284-7

- My American Century (1997) ISBN 1-59558-177-4

- The Spectator: Talk About Movies and Plays With Those Who Make Them (1999) ISBN 1-56584-633-8

- Will the Circle Be Unbroken: Reflections on Death, Rebirth and Hunger for a Faith (2001) ISBN 0-641-75937-1

- Hope Dies Last: Keeping the Faith in Difficult Times (2003) ISBN 1-56584-837-3

- And They All Sang: Adventures of an Eclectic Disc Jockey (2005) ISBN 1-59558-003-4

- Touch and Go (2007) ISBN 1-59558-043-3

- P.S. Further Thoughts from a Lifetime of Listening (2008) ISBN 1-59558-423-4

References

- Rick Kogan (31 October 2008). "Studs Terkel dies". The Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2008-11-13.

- William Grimes (31 October 2008). "Studs Terkel, Listener to Americans, Dies at 96". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-11-17.

- Studs Terkel (2012). Studs Terkel's Chicago. New York: New Press. pp. 46–47. ISBN 9781595587183.

- Jane Ammeson. "Storytelling with Studs Terkel". Chicago Life. Archived from the original on 2007-08-08.

- Richard Sisson; Christian K. Zacher; Andrew Robert Lee Cayton (2007). The American Midwest: an interpretive encyclopedia. Indiana University Press. p. 498.

Previous Terkel radio work included WENR (1944 Wax Museum), WCFL (beginning November 30, 1947). A TV show (Stud's Place, beginning November, 1949) lasted to 1951. - "Division Street America by Studs Terkel". Retrieved September 27, 2016.

- Peter Lyon (February 5, 1967). "Chicago Voices". The New York Times. Retrieved September 27, 2016.

- "Studs Terkel, Recordings from Division Street". Chicago History Museum. Retrieved September 27, 2016. 23 original audio recordings as aired by Terkel

- "Author Studs Terkel, Other Prominent Chicagoans Join in Challenge to AT&T Sharing of Telephone Records with the National Security Agency". aclu.org. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- "Judge Drops Studs Terkel NSA Lawsuit". NewsMax.com. July 25, 2006. Archived from the original on January 20, 2008.

- Gary Younge (January 23, 2008). "Let Me Tell You A Story". The Guardian.

- "Terkel records life in a 'Touch and Go' way". USA Today. December 19, 2007. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- Jay Allison; Dan Gediman, eds. (2006). This I Believe: The Personal Philosophies of Remarkable Men and Women.

- "Studs Terkel — Life, Faith, and Death -". onbeing.org. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- Rick Kogan (2008-10-31). "Studs Terkel dies". Chicago Tribune.

- "Studs Terkel". BBC News. February 4, 2008. Retrieved April 1, 2010.

- Edward Lifson (November 23, 2008). "Studs for Obama". Huffington Post.

-

American prize-winning author Studs Terkel dead at 96 at Wikinews

American prize-winning author Studs Terkel dead at 96 at Wikinews - "Louis Daniel Armstrong talks with Studs Terkel on WFMT; 1962/6/24". Studs Terkel Radio Archive. June 24, 1962. Retrieved September 27, 2016.

- "Poet Laureate Gwendolyn Brooks talks with Studs – Poetry Month; 1967". Studs Terkel Radio Archive. 1967. Retrieved September 27, 2016.

- "Studs Terkel's Music Interviews". Library of Congress. 2014. Retrieved September 27, 2016. Includes excerpts of interviews with Bob Dylan, Janis Joplin, Oscar Petersen, and Memphis Slim.

- "Library Collaborates With Chicago History Museum To Preserve Radio Icon Studs Terkel's Historic Recordings". loc.gov. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- "The Working Tapes of Studs Terkel". April 4, 2019.

- "Commencement History". Archived from the original on 2015-05-18.

- "Clinton Gives Medals in Arts and Humanities to Studs Terkel, Others". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved 2020-02-23.

- "Studs Terkel Accepts the 1997 Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters". Nationalbook.org. 24 February 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- "Inductees to the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame". Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on October 6, 2010.

- "Laureates by Year". The Lincoln Academy of Illinois. Retrieved 2016-03-07.

- "Dayton Literary Peace Prize – Award Winners". Dayton Literary Peace Prize Foundation. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- "Studs Terkel to receive first Dayton literary prize". USA Today. AP. July 19, 2006.

- "Studs Terkel". Chicago Literary Hall of Fame. 2010. Retrieved 2017-10-15.

- "Studs Terkel". Nationalbook.org. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- Terkel, Studs (2007). Touch and Go: A Memoir. New York: The New Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-59558-587-5.

External links

- Official website

- Studs Terkel at Curlie

- Works by or about Studs Terkel in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Studs Terkel at IMDb

- Studs Terkel on National Public Radio in 1985

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Portrait of Louis "Studs" Terkel seated at a restaurant table in Los Angeles, California, 1970. Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive (Collection 1429). UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles.