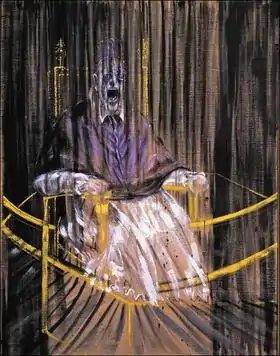

Study after Velázquez's Portrait of Pope Innocent X

Study after Velázquez's Portrait of Pope Innocent X is a 1953 painting by the artist Francis Bacon. The work shows a distorted version of the Portrait of Innocent X painted by Spanish artist Diego Velázquez in 1650. The work is one of the first[1] in a series of around 50[2] variants of the Velázquez painting which Bacon executed throughout the 1950s and early 1960s.[3][4] The paintings are widely regarded as highly successful modern re-interpretations of a classic of the western canon of visual art.

Of the old masters, Bacon favored Titian, Rembrandt, Velázquez and Francisco Goya's late works.[5] He kept an extensive inventory of images for source material, but preferred not to confront the major works in person; he viewed Portrait of Innocent X only once. Having deliberately avoided it for years, he only saw it in person much later in his life.

The canvas is one of Bacon's masterpieces, completed when he was at the height of his creative powers.[6] It has been the subject of detailed analysis by several major scholars. David Sylvester described it as, along with Head VI, "the finest pope Bacon produced".[7]

Pope series

Velázquez had been commissioned by Innocent X to paint the portrait as from life, a prime motive being prestige. However, Velázquez did not flatter his sitter, and the painting is noted for its realism, in that it is an unflinching portrait of a highly intelligent, shrewd, aging man.

Bacon never painted from life, preferring to use a variety of visual source material, including photographs both found (including in movie stills, medical text books and 19th century journals) and commissioned. Equally, Bacon rarely worked from commission, and could portray the pope in an even less flattering light; according to art critic Arim Zweite, "in a sinister manner, in cavernous dungeons, afflicted by an emotional outburst and devoid of any authority".[8]

Although Bacon avoided seeing the original, the painting remains the single greatest influence on him; its presence can be seen in many of his best works from the late 1940s to the early 1960s. In Bacon's version of the 17th century masterpiece, the Pope is shown screaming yet his voice is "silenced" by the enclosing drapes and dark rich colors. The dark colors of the background lend a grotesque and nightmarish tone to the painting.[9] Although a noted bon vivant, Bacon closely guarded his private life, working habits, and thought processes. He produced some 50 paintings of popes, but destroyed a great many that he was unhappy with.[10]

_001b.jpg.webp) Titian, Portrait of Pope Paul III, 1545–46

Titian, Portrait of Pope Paul III, 1545–46 Diego Velázquez, Portrait of Innocent X, 1650. Galleria Doria Pamphilj, Rome

Diego Velázquez, Portrait of Innocent X, 1650. Galleria Doria Pamphilj, Rome Titian, Portrait of Cardinal Filippo Archinto, 1558. Philadelphia Museum of Art

Titian, Portrait of Cardinal Filippo Archinto, 1558. Philadelphia Museum of Art

Description and themes

As with many other of Bacon's popes, the painting is dominated by purple vestments. Bacon's palette changed in 1953, and his paintings became darker, the earlier blues were replaced by velvet purples while his overall tone became more nocturnal. The soft focused and filled in backgrounds disappeared, replaced by flat dark spaces which in some cases were merely the untreated blank canvas.[12] The pleated curtains of the backdrop are rendered transparent and appear to fall through and encircle the Pope's screaming face.[13]

Although his earlier works, dominated by harsh orange pigments,[14] were hardly cheerful, it has been suggested a reason his pallet became darker is that he was scarred by the ending of his tumultuous and sometimes violent relationship with Peter Lacy, whom he later described as the love of his life.[15] This also in part explains why Bacon began to focus on representations of father figures such as popes - Lacy was a much older and accomplished man and had been the dominant partner.[15]

The man is clearly identifiable as a pope from his clothing.[16] He seems trapped and isolated within the outlines of an abstract three-dimensional glass cage. The framing device, described by Sylvester as a "space-frame", features heavily throughout the artist's later career.[17]

Cage

Horizontal metal frames[2] and draped curtains often featured in Bacon's 1950s and 1960s paintings.[18] The motif may have been borrowed from the sculptors Alberto Giacometti and Henry Moore, both of whom Bacon greatly admired; he often corresponded and met with Giacometti.[19] Giacometti had employed the device in The Nose (1947) and The Cage (1950), while Moore used similar frames in his 1952 bronze Maquette for King and Queen.[20] Bacon's use of frames suggests imprisonment to many critics.[21][22]

Vertical folds

The vertical folds resemble curtains. Veils, curtains, and similar structures appear in Bacon's earliest works, notably the 1949 Study from the Human Body, always in front of, rather than behind, the figure.[23] Their source may be Titian's 1558 Portrait of Cardinal Filippo Archinto.

The folds emphasise the figure's isolation, and were drawn from devices used by Edgar Degas in the late 19th century, which Bacon described as "shuttering". Bacon said that to him the device meant that the "sensation doesn't come straight out at you but slides slowly and gently across".[24]

Meaning

When asked why he was compelled to revisit Velázquez's Portrait again and again, Bacon replied that he had nothing against popes, but merely sought "an excuse to use these colours, and you can't give ordinary clothes that purple colour without getting into a sort of false fauve manner".[25] At the time Bacon was coming to terms with the death of a cold, disciplinarian father, his early, illicit sexual encounters, and a very destructive sadomasochistic approach to sex.[26]

Almost all of the popes are shown within cage-like structures and screaming or about to scream. Bacon identified as a Nietzschean and atheist, and some contemporary critics saw the series as symbolic execution scenes, as if Bacon sought to enact Nietzsche's declaration that "God is dead" by killing his representative on Earth. Other critics see the series as symbolizing the killing of a father figure.[27] However Bacon balked at such literal translations, and later said that it was Velázquez himself he sought to "triumph over." He said that in the same way that Velázquez cooled Titian, he sought to "cool" Velázquez.[27]

References

- Bacon's first full realised pope is 1949's Head VI.

- Zweite (2006), p. 116

- Schmied (1996), p. 17

- Francis Bacon 'screaming pope' painting to be sold at auction". The Guardian, 27 September 2012. Retrieved 28 May, 2017

- He also thought very highly of Paul Cézanne

- Sylvester (2000), p. 78

- Sylvester (2000), p. 88

- Excepting 1982's Three Studies for Portrait (Mick Jagger), a series he produced specifically for showings at the Hanover Gallery in the late 1940s and early 1950s

- Schmied (1996), 20

- Farr et al (1999), p. 31

- Peppiatt (1996), p. 30

- Sylvester (2000), p. 81

- Peppiatt (1996), p. 148

- Gale, Matthew. "Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, circa 1944". Tate Gallery, November 1998

- Brown, Mark. "Portrait of Francis Bacon's violent lover to be auctioned at Sotheby's". The Guardian, 8 April 2013. Retrieved 28 May, 2017

- Peppiatt (1996), p. 129

- Sylvester (2000), p. 36

- van Alphen (1992), p. 108

- Sylvester (2000), pp. 8–9

- Sylvester (2000), p. 36

- Sylvester (2000), p. 37

- Farr et al. (1999), p. 60

- Zweite (2006), p. 208

- Dawson (2000), p. 53

- Peppiatt (1996), p. 147

- Barker, Oliver. Francis Bacon, 'Untitled (Pope)', in conversation with Michael Peppiatt. London: Sotheby's, October 23, 2012

- Zweite (2006), p. 117

Sources

- Davies, Hugh & Yard, Sally, Francis Bacon. (New York) Cross River Press. ISBN 0-89659-447-5

- Dawson, Barbara; Sylvester, David. Francis Bacon in Dublin. London: Thames & Hudson, 2000. ISBN 0-500-28254-4

- Peppiatt, Michael. Anatomy of an Enigma. Westview Press, 1996. ISBN 0-8133-3520-5

- Russell, John. Francis Bacon. New York: Norton, 1971. ISBN 0-500-20169-2

- Schmied, Wieland. Francis Bacon: Commitment and Conflict. Munich: Prestel, 1996. ISBN 3-7913-1664-8

- Sylvester, David. Looking back at Francis Bacon. London: Thames and Hudson, 2000. ISBN 0-500-01994-0

- van Alphen, Ernst. Francis Bacon and the Loss of Self. London: Reaktion Books, 1992. ISBN 0-948462-33-7

- Zweite, Armin. The Violence of the Real. London: Thames and Hudson, 2006. ISBN 0-500-09335-0