Susan Rosenberg

Susan Lisa Rosenberg (born October 5, 1955)[1] is an American activist, writer, advocate for social justice and prisoners' rights and a former terrorist. From the late 1970s into the mid-1980s, Rosenberg was active in the far-left revolutionary terrorist May 19th Communist Organization ("M19CO") which, according to a contemporaneous FBI report, "openly advocate[d] the overthrow of the U.S. Government through armed struggle and the use of violence".[2] M19CO provided support to an offshoot of the Black Liberation Army, including in armored truck robberies, and later engaged in bombings of government buildings.[3]

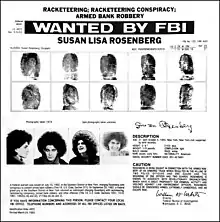

After living as a fugitive for two years, Rosenberg was arrested in 1984 while in possession of a large cache of explosives and firearms over 750 lbs and automatic weapons. She had also been sought as an accomplice in the 1979 prison escape of Assata Shakur and in the 1981 Brink's robbery that resulted in the deaths of two police and a guard,[4] although she was never charged in either case.

Rosenberg was sentenced to 58 years' imprisonment on the weapons and explosives charges. She spent 16 years in prison, during which she became a poet, author, and AIDS activist. Her sentence was commuted to time served by President Bill Clinton on January 20, 2001,[5] his final day in office.[6][7]

Early life

Rosenberg was born into a middle-class Jewish family in Manhattan. Her father was a dentist and her mother a theatrical producer. She attended the progressive Walden School and later went to Barnard College.[8] She left Barnard and became a drug counselor at Lincoln Hospital in The Bronx, eventually becoming licensed in the practice of Chinese medicine and acupuncture.[8] She also worked as an anti-drug counselor and acupuncturist at health centers in Harlem, including the Black Acupuncture Advisory of North America.[9]

Activism and imprisonment

In an interview with the radio show Democracy Now, Rosenberg said that she was "totally and profoundly influenced by the revolutionary movements of the '60s and '70s". She became active in feminist causes, and worked in support of the Puerto Rican independence movement and the fight against the FBI's COINTELPRO program.[6][10] She also joined the May 19th Communist Organization, which worked in support of the Black Liberation Army and its offshoots (including assistance in armored truck robberies), the Weather Underground and other revolutionary organizations.[11] Rosenberg was charged with a role in the 1983 United States Senate bombing, the U.S. National War College and the New York Patrolmen's Benevolent Association, but the charges were dropped as part of a plea deal by other members of her group.[12][7][13]

Arrested for explosives possession in November 1984 after two years underground, she was convicted by a jury in March 1985, and given a 58-year-sentence. Supporters said this was sixteen times the national average for such offenses.[14] Her lawyers contend that, had the case not been politically charged, Rosenberg would have received a five-year sentence.[6]

Rosenberg was one of the first two inmates of the High Security Unit (HSU), a high-security isolation unit in the basement of the Federal Correctional Institution (currently the Federal Medical Center) in Lexington, Kentucky.[15][16][17] Allegations were made that the unit was an experimental underground political prison that practiced isolation and sensory deprivation.[18] The women were subject to 24-hour camera surveillance and frequent strip searches, and were given only limited access to visitors or to exercise.[19] After touring the unit, the American Civil Liberties Union denounced it as a "living tomb", and Amnesty International called it "deliberately and gratuitously oppressive".[20] After a lawsuit was brought by the ACLU and other organizations, the unit was ordered closed by a federal judge in 1988 and the prisoners transferred to regular cells.[15]

Rosenberg was transferred to various prisons around the country, from FCI Coleman, Florida, FCI Dublin, California and, finally, FCI Danbury, Connecticut. While in prison, she devoted herself to writing and to activism around AIDS, and obtained a master's degree from Antioch University.[9] Speaking at a 2007 forum, Rosenberg said that writing "became the mechanism by which to save my own sanity". She added that she began writing partly because the intense isolation of prison was threatening to cut her off completely from the real world and that she did not want to lose her connection to that world.[21]

Release

Rosenberg's sentence was commuted by President Bill Clinton on January 20, 2001, his last day in office, to the more than 16 years' time served. Her commutation produced a wave of criticism by police and New York elected officials.[22]

After her release, Rosenberg became the communications director for the American Jewish World Service, an international development and human rights organization, based in New York City. She also continued her work as an anti-prison activist, and taught literature at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. After teaching for four semesters there as an adjunct instructor, the CUNY administration, responding to political pressure, forced John Jay College to end its association with Rosenberg, and her contract with the school was allowed to expire without her being rehired.[23]

In 2004, Hamilton College offered her a position to teach a for-credit month-long seminar, "Resistance Memoirs: Writing, Identity and Change". Some professors, alumni and parents of students objected and as a result of the ongoing protests, she declined the offer.[24]

As of 2020, Rosenberg serves as vice chair of the board of directors of Thousand Currents, a non-profit foundation that sponsors the fundraising and does administrative work for the Black Lives Matter global network, among other clients.[25]

Writing

In 2011, Rosenberg published a memoir of her time in prison called, An American Radical: A Political Prisoner In My Own Country. Kirkus Reviews said of the book, "Articulate and clear-eyed, Rosenberg's memoir memorably records the struggles of a woman determined to be the agent of her own life."[26][27]

- Rosenberg, Susan (2011). An American Radical: A Political Prisoner In My Own Country. New York: Kensington Publishing Corp. ISBN 978-0806533049.

See also

References

Citations

- Rosenau 2020.

- FBI Analysis of Terrorist incidents and Terrorist related activities in the United States (PDF), US Department of Justice National Institute of Justice, 1984

- Rosenau, William (April 3, 2020). "The Dark History of America's First Female Terrorist Group".

- Raab, Selwyn (1984-12-01). "Radical fugitive in brink's robbery arrested". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-04-19.

A Weather Underground fugitive who had been sought for two years in the $1.6 million Brink's robbery and murder case has been arrested in New Jersey by a police officer who became suspicious of her ill-fitting wig.

- "Clinton Pardon's List". The Washington Post. Associated Press. January 20, 2001. Retrieved July 23, 2017.

- "An Exclusive Interview with Susan Rosenberg After President Clinton Granted Her Executive clemency". Democracy Now!. 2001-01-23. Retrieved 2013-05-03.

- Christopher, Tommy (April 16, 2008). "Clinton has Bigger Weather Underground Problem". Political Machine. AOL News.

- Hoffman, Merle (1989). "America's Most Dangerous Woman?". On The Issues Magazine. Vol. 13. Retrieved 2013-05-03.

- "Susan Rosenberg". PEN America. Archived from the original on August 7, 2007.

- Berger 2006, p. 206.

- "Full text of "The Way The Wind Blew: A History Of The Weather Underground"". Retrieved 2013-05-03.

- "Judge hands 20 years to bomber". Victoria Advocate. December 7, 1990.

- "3 Radicals Agree to Plead Guilty in Bombing Case". The New York Times. 1990-09-06. Retrieved 2008-11-03.

Three radicals will plead guilty to setting off bombs at the nation's Capitol and seven other sites in the early 1980s. The Government has agreed to drop charges against three other people.

- Rosenberg 2005, p. 91.

- "Judge Bars U.S. From Isolating Prisoners for Political Beliefs", The New York Times, July 17, 1988. Accessed 19 October 2008

- Susie Day (July 1, 2001). "Cruel But Not Unusual: The Punishment of Women in U.S. Prisons, An Interview with Marilyn Buck and Laura Whitehorn". Monthly Review. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- "Reuben, William A.; Norman, Carlos. "Brainwashing in America? The women of Lexington Prison". The Nation, 1987. Accessed 19 October 2008". Retrieved 2013-05-03 – via Questia Online Library.

- Rodriguez, Dylan. Forced Passages: Imprisoned Radical Intellectuals and the U.S. Prison Regime. University of Minnesota Press, 2006. ISBN 0-8166-4560-4. p. 189

- Leonard 1990, p. 68.

- Kauffman 2009, p. 338.

- "Words Under Confinement". PEN America. Archived from the original on October 4, 2012.

- Lipton, Eric (January 22, 2001). "Officials Criticize Clinton's Pardon of an Ex-Terrorist". The New York Times.

- "Ever Vulnerable Adjuncts". Inside Higher Ed. 2013-04-29. Retrieved 2013-05-03.

- Kimball, Roger (December 3, 2004). "Meet the Newest Member of the Faculty – Clinton pardons a terrorist, and now she's teaching in Clinton, N.Y." The Wall Street Journal – via Opinionjournal.com (via waybackmachine).

- "Thousand Currents Income Tax Return". propublica.org.

- An American Radical Kirkus Reviews. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- "Home | Prison Memoir: An American Radical | Political Prisoner in My Own Country". An American Radical. 2011-07-11. Retrieved 2013-05-03.

Sources

- Berger, Dan (2006). Outlaws of America: The Weather Underground and the Politics of Solidarity. AK Press. ISBN 978-1-904859-41-3.

- Kauffman, Linda S. (2009). "The Long Goodbye". Feminisms Redux: An Anthology of Literary Theory and Criticism. Rutgers University Press. GGKEY:Q1ZAYYJ2Y7H.

- Leonard, John (25 June 1990). "Television". New York. ISSN 0028-7369.

- Rosenau, William (2020). Tonight We Bombed the U.S. Capitol: The Explosive Story of M19, America's First Female Terrorist Group. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-5011-7012-6.

- Rosenberg, Susan (2005). "Ch.9". In Joy James (ed.). New Abolitionists, The: (Neo)slave Narratives And Contemporary Prison Writings. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-8310-7.

External links

- Susan Rosenberg papers at the Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College Special Collections