Symphony No. 8 (Sibelius)

Jean Sibelius's Symphony No. 8 was his final major compositional project, occupying him intermittently from the mid-1920s until around 1938, though he never published it. During this time Sibelius was at the peak of his fame, a national figure in his native Finland and a composer of international stature. A fair copy of at least the first movement was made, but how much of the Eighth Symphony was completed is unknown. Sibelius repeatedly refused to release it for performance, though he continued to assert that he was working on it even after he had, according to later reports from his family, burned the score and associated material, probably in 1945.

Much of Sibelius's reputation, during his lifetime and subsequently, derived from his work as a symphonist. His Seventh Symphony of 1924 has been widely recognised as a landmark in the development of symphonic form, and at the time there was no reason to suppose that the flow of innovative orchestral works would not continue. However, after the symphonic poem Tapiola, completed in 1926, his output was confined to relatively minor pieces and revisions to earlier works. During the 1930s the Eighth Symphony's premiere was promised to Serge Koussevitzky and the Boston Symphony Orchestra on several occasions, but as each scheduled date approached Sibelius demurred, claiming that the work was not ready for performance. Similar promises made to the British conductor Basil Cameron and to the Finnish Georg Schnéevoigt likewise proved illusory. It is thought that Sibelius's perfectionism and exalted reputation prevented him ever completing the symphony to his satisfaction; he wanted it to be even better than his Seventh.

After Sibelius's death in 1957, news of the Eighth Symphony's destruction was made public, and it was assumed that the work had disappeared forever. But in the 1990s, when the composer's many notebooks and sketches were being catalogued, scholars first raised the possibility that fragments of the music for the lost symphony might have survived. Since then, several short manuscript sketches have been tentatively identified with the Eighth, three of which (comprising less than three minutes of music) were recorded by the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra in 2011. While a few musicologists have speculated that, if further fragments can be identified, it may be possible to reconstruct the entire work, others have suggested that this is unlikely given the ambiguity of the extant material. The propriety of publicly performing music that Sibelius himself had rejected has also been questioned.

Background

Jean Sibelius was born in 1865 in Finland, since 1809 an autonomous grand duchy within the Russian Empire having earlier been under Swedish control for many centuries.[1] The country remained divided between a culturally dominant Swedish-speaking minority, to which the Sibelius family belonged, and a more nationalistically-minded Finnish-speaking, or "Fennoman" majority.[2] In about 1889 Sibelius met his future wife, Aino Järnefelt, who came from a staunch Fennoman family.[3] Sibelius's association with the Järnefelts helped to awaken and develop his own nationalism; in 1892, the year of his marriage to Aino, he completed his first overtly nationalistic work, the symphonic suite Kullervo.[4] Through the 1890s, as Russian control over the duchy grew increasingly oppressive, Sibelius produced a series of works reflecting Finnish resistance to foreign rule, culminating in the tone poem Finlandia.[5]

Sibelius's national stature was recognised in 1897 when he was awarded a state pension to enable him to spend more time composing.[6] In 1904 he and Aino settled in Ainola, a country residence he built on the shores of Lake Tuusula in Järvenpää, where they lived for the remainder of their lives.[7] Although life at Ainola was not always calm and carefree—Sibelius was often in debt and prone to bouts of heavy drinking—he managed over the following 20 years to produce a large output of orchestral works, chamber music, piano pieces and songs, as well as lighter music.[8] His popularity spread across Europe to the United States where, during a triumphant tour in 1914, he was awarded an honorary doctorate by Yale University.[9] At home his status was such that his 50th birthday celebrations in 1915 were a national event, the centrepiece of which was the Helsinki premiere of his Fifth Symphony.[10]

By the mid-1920s Sibelius had acquired the status of a living national monument and was the principal cultural ambassador of his country, independent since 1917.[11] According to his biographer Guy Rickards, he invested "his most crucial inspiration" into the seven symphonies he composed between 1898 and 1924.[12] The Sibelius scholar James Hepokoski considers the compact, single-movement Seventh Symphony, which Sibelius completed in 1924, to be the composer's most remarkable symphonic achievement, "the consummate realization of his late-style rethinking of form".[10] It was followed in 1926 by Tapiola, a tone poem in which, says Rickards, Sibelius "pushed orchestral resources into quite new regions ...Tapiola was thirty or forty years ahead of its time".[13]

Composition

Beginnings

The first reference to the Eighth Symphony in Sibelius's diary is an undated entry from September 1926: “I offered to create something for America.”[14] However, some of the initial ideas for the new symphony were almost certainly set down earlier, since it was Sibelius's compositional habit to set aside themes and motifs for use in later projects. Thus, one of the extant sketches for his Seventh Symphony, on which he was engaged in 1923–24, contains a ringed motif marked "VIII".[15] By the autumn of 1927 Sibelius was able to inform the New York Times music critic Olin Downes—one of his greatest admirers—that he had set down two movements of the Eighth on paper and had composed the rest in his head.[16]

Early in 1928 Sibelius made one of his regular visits to Berlin, to imbibe the city's musical life and to compose. He sent positive work-in-progress reports to Aino: the symphony, he said, will be "wonderful".[16] Back home in Ainola in September, he told his sister that he was "writing a new work, which will be sent to America. It will still need time. But it will turn out well."[17] In December 1928, however, when his Danish publisher Wilhelm Hansen asked him how the work was developing, Sibelius was less forthcoming; the symphony existed, he said, only in his head. Thereafter Sibelius's reports of the symphony's progress became equivocal, sometimes contradictory, and difficult to follow.[16]

Progress and prevarication

Probably at the instigation of Downes, Sibelius had promised the world premiere of his new symphony to Serge Koussevitzky and the Boston Symphony Orchestra.[18] For several years, in a protracted correspondence with the conductor and Downes, Sibelius hesitated and prevaricated. In January 1930 he said the symphony was "not nearly ready and I cannot say when it will be ready", but in August that year he told Koussevitzky that a performance in the spring of 1931 was possible. Nothing resulted from this.[19] In the summer of 1931 Sibelius told Downes that not only was the Eighth Symphony almost ready for the printers, he also had several other new works pending.[20] Thus encouraged, in December 1931 Koussevitzky used the Boston Evening Transcript to announce the work for the orchestra's 1931–32 season. This brought a swift telegram from Sibelius, to the effect that the symphony would not, after all, be ready for that season.[19]

Koussevitzky then decided to perform all of Sibelius's symphonies in the Boston Symphony's 1932–33 season, with the world premiere of the Eighth as the culmination. In June 1932 Sibelius wrote to Koussevitzky suggesting that the Eighth be scheduled for the end of October. A week later he retracted: "I am very disturbed about it. Please do not announce the performance."[19] Further promises, for December 1932 and January 1933, brought forth no scores. Koussevitzky was by now losing hope, yet he inquired once more, in the summer of 1933. Sibelius was evasive; he made no promise of delivery but would "return to the matter at a later date". So far as Koussevitzky and the Boston Symphony were concerned, the matter ended there.[16] Sibelius had made agreements with other conductors; he had promised the European premiere to Basil Cameron and the Royal Philharmonic Society,[17] and the first Finnish performance to Georg Schnéevoigt, who had recently taken over direction of the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra.[21] These arrangements were, however, subject to the illusory Boston premiere, and thus were stillborn.[17] Later in the decade, Eugene Ormandy, a fervent admirer of Sibelius who directed the Philadelphia Orchestra from 1936, is thought to have lobbied strongly for the right to perform the premiere, should the symphony in due course emerge.[22]

During his procrastinations with Koussevitzky, Sibelius continued to work on the symphony. In 1931 he again spent time in Berlin, writing to Aino in May 1931 that "the symphony is advancing with rapid strides". Progress was interrupted by illness, but towards the end of the year Sibelius was confidently asserting that "I am writing my eighth symphony and I am full of youth. How can this be explained?"[23] In May 1933, as he continued to deny Koussevitzky, Sibelius wrote in his diary that he was deeply immersed in composition: "It is as if I had come home ... I'm taking everything in another way, more deeply. A gypsy within me. Romantic."[23] Later that summer he informed a journalist that his new symphony was nearly complete: "It will be the reckoning of my whole existence – sixty-eight years. It will probably be my last. Eight symphonies and a hundred songs. It has to be enough."[17]

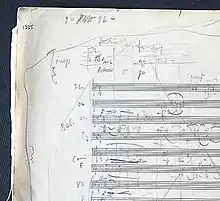

At some stage in that summer the formal copying of the symphony began. On 4 September 1933 Paul Voigt, Sibelius's long-time copyist, sent a bill for making a fair copy of the first movement—23 pages of music. Sibelius informed him—the note survives—that the complete manuscript would be about eight times as long as this excerpt, indicating that the symphony might be on a larger scale than any of its seven predecessors.[20] Aino Sibelius later recalled other visits to Voigt that autumn at which Sibelius, whose mood she described as gloomy and taciturn, delivered further piles of music manuscript to the copyist.[16]

Limbo

Olin Downes, writing to Sibelius in 1937[24]

Various reports appeared to confirm that the symphony's release was imminent. The Finnish composer Leevi Madetoja mentioned in 1934 that the work was virtually complete;[25] an article by the Swedish journalist Kurt Nordfors indicated that two movements were complete and the rest sketched out.[16] As pressure to produce the symphony increased, Sibelius became increasingly withdrawn and unwilling to discuss his progress. In December 1935, during an interview in connection with his 70th birthday celebrations, he indicated that he had discarded a whole year's work; this pointed to a full-scale revision of the Eighth.[26] However, when The Times's correspondent asked for details of the work's progress Sibelius became irritated. He was furious when Downes continued to pester him for information, on one occasion shouting "Ich kann nicht!" ("I cannot!").[18][27]

A receipt found among Sibelius's papers refers to a "Symphonie" being bound by the firm of Weilin & Göös in August 1938. While it is not established that this transaction related to the Eighth, the Sibelius scholar Kari Kilpeläinen points out that none of the earlier symphony scores carry the unnumbered heading "Symphonie", and asks: "Could he have omitted the number to prevent news of the now completed Eighth from spreading? Or did he not give the work a number at all, because he was not satisfied with it?"[16] The composer's daughter Katarina spoke of the self-doubt that afflicted her father at this time, aggravated by the continuing expectations and fuss that surrounded the Eighth Symphony. "He wanted it to be better than the other symphonies. Finally it became a burden, even though so much of it had already been written down. In the end I don't know whether he would have accepted what he had written."[26]

Sibelius remained in Finland during the Winter War of 1939–40, despite offers of asylum in the United States. After the war ended in March 1940 he moved with his family to an apartment on Kammiokatu (later renamed Sibeliuksenkatu or 'Sibelius Street' in his honour) in the Töölö district of Helsinki, where they remained for a year. During that time they were visited by the pianist Martti Paavola, who was able to examine the contents of Sibelius's safe. Paavola later reported to his pupil Einar Englund that among the music kept there was a symphony, "most likely the Eighth".[28]

Destruction

Back in Ainola, Sibelius busied himself by making new arrangements of old songs. However, his mind returned frequently to the now apparently moribund symphony. In February 1943 he told his secretary, Santeri Levas, that he hoped to complete a "great work" before he died, but blamed the war for his inability to make progress: "I cannot sleep at nights when I think about it."[28] In June he discussed the symphony with his future son-in-law Jussi Jalas and provided another reason for its non-completion: "For each of my symphonies I have developed a special technique. It can't be something superficial, it has to be something that has been lived though. In my new work I am struggling with precisely these issues." Sibelius also told Jalas that all rough sketches and drafts were to be burned after his death; he did not want anyone labelling these rejected scraps as "Sibelius letzten [sic] Gedanken" (Sibelius's last thoughts).[28]

At some time in the mid-1940s, probably in summer 1945,[29] Sibelius and Aino together burned a large number of the composer's manuscripts on the stove in the dining room at Ainola. There is no record of what was burned; while most commentators assume that the Eighth Symphony was among the works destroyed, Kilpeläinen observes that there had been at least two manuscripts of the work—the original and Voigt's copy—as well as sketches and fragments of earlier versions. It is possible, says Kilpeläinen, that Sibelius may not have burned them all.[16] Aino, who found the process very painful, recalled later that the burning appeared to ease Sibelius's mind: "After this, my husband appeared calmer and his attitude was more optimistic. It was a happy time".[30] The most optimistic interpretation of his action, according to The Philadelphia Inquirer’s music critic David Patrick Stearns, is that he got rid of old drafts of the symphony to clear his mind for a fresh start.[22] In 1947, after visiting Ainola, the conductor Nils-Eric Fougstedt claimed to have seen a copy of the Eighth on the shelf, with separate choral parts. The musicologist Erkki Salmenhaara posits the idea of two burnings: that of 1945 which destroyed early material, and another after Sibelius finally recognised that he could never complete the work to his satisfaction.[16]

Although Sibelius informed his secretary in late August 1945 that the symphony had been burned,[29] the matter remained a secret confined to the composer's private circle. During the remaining years of his life, Sibelius from time to time hinted that the Eighth Symphony project was still alive. In August 1945 he wrote to Basil Cameron: "I have finished my eighth symphony several times, but I am still not satisfied with it. I will be delighted to hand it over to you when the time comes."[16] In fact, after the burning he had altogether abandoned creative composing; in 1951, when the Royal Philharmonic Society requested a work to mark the 1951 Festival of Britain, Sibelius declined.[31] As late as 1953 he told his secretary Levas that he was working on the symphony "in his mind";[32] only in 1954 did he admit, in a letter to the widow of his friend Adolf Paul, that it would never be completed.[33] Sibelius died on 20 September 1957; the next day his daughter Eva Paloheimo announced publicly that the Eighth Symphony did not exist. The burning of the manuscript became generally known later, when Aino revealed the fact to the composer's biographer Erik W. Tawaststjerna.[20]

Mark McKenna, "Who Stopped the Music?" (November 2012)[18]

Critics and commentators have pondered the reasons why Sibelius finally abandoned the symphony. Throughout his life he was prone to depression[34] and often suffered crises of self-confidence. Alex Ross, in The New Yorker, quotes an entry from the composer's 1927 diary, when the Eighth Symphony was allegedly under way:

"This loneliness is driving me crazy. [...] To be able to live in the first place, I must have alcohol. Wine or whisky. That’s the matter. Abused, alone, and all my real friends are dead. My current prestige here at home is rock-bottom. Impossible to work. If only there were a solution."[35]

Writers have pointed to the hand tremor that made writing difficult and to the alcoholism that afflicted him at numerous stages of his life.[22] Others have argued that Sibelius's exalted status as a national hero effectively silenced him; he became afraid that any further major work would not live up to the expectations of the adoring nation.[18] Andrew Barnett, another of the composer's many biographers, points to Sibelius's intense self-criticism; he would withhold or suppress anything that failed to meet his self-imposed standards: "It was this attitude that brought about the destruction of the Eighth Symphony, but the very same trait forced him to keep on revising the Fifth until it was perfect."[36] The historian Mark McKenna agrees that Sibelius became stifled by a combination of perfectionism and increasing self-doubt. The myth, sustained for more than 15 years, that Sibelius was still working on the symphony was, according to McKenna, a deliberate fiction: "To admit that he had stopped completely would be to admit the unthinkable—that he was no longer a composer".[18]

Discoveries

After his death Sibelius, though remaining popular with the general public, was frequently denigrated by critics who found his music dated and tedious.[37] René Leibowitz, a proponent of the music of Arnold Schoenberg, published a pamphlet describing Sibelius as "the worst composer in the world";[38] others dismissed him as irrelevant in what was perceived for a time as an irresistible movement towards atonality.[39] This climate diminished curiosity about the existence of material from a possible Sibelius Eighth, until late in the 20th century, when critical interest in the composer revived. In 1995 Kilpeläinen, who had published a survey of the Sibelius manuscripts held in the Helsinki University Library, wrote that all that could definitely be connected to the Eighth Symphony were a single page from a draft score and the ringed melody fragment marked "VIII" within the Seventh Symphony sketches. He added, however, that the library contained further Sibelius sketches from the late 1920s and early 1930s, some of which are akin to the ringed fragment and which could conceivably have been intended for the Eighth Symphony. Kilpeläinen also revealed that "[j]ust recently various documents have come to light which no one dreamt even existed. Maybe there are still some clues to the 8th Symphony hidden away and just waiting for some scholar to discover them."[16]

In 2004, in an article entitled "On Some Apparent Sketches for Sibelius's Eighth Symphony", the musical theorist Nors Josephson identifies around 20 manuscripts or fragments held in the Helsinki University Library as being relevant to the symphony and concludes that: "Given the abundance of preserved material for this work, one looks forward with great anticipation to a thoughtful, meticulous completion of the entire composition".[25] Another Sibelius scholar, Timo Virtanen, has examined the same material and is more restrained, concluding that although some of the sketches may relate to the Eighth Symphony, it is not possible to determine exactly which, if any, these are. Even the fragment marked "VIII", he maintains, cannot with certainty be said to relate to the symphony, since Sibelius often used both Roman and Arabic numerals to refer to themes, motifs or passages within a composition. Virtanen provides a further note of caution: "We should be aware that [the fragments] are, after all, drafts: unfinished as music, and representing only a certain stage in planning a new composition".[40]

Despite his reservations, in October 2011 Virtanen cooperated with another scholar, Vesa Sirén, to prepare three of the more developed fragments for performance. The sketches were copied and tidied, but nothing not written by Sibelius was added to the material. Permission from the Sibelius Rights Holders was secured, and John Storgårds, chief conductor of the Helsinki Philharmonic, agreed to play and record these excerpts at the orchestra's rehearsal session on 30 October 2011. The pieces comprise an opening segment of about a minute's duration, an eight-second fragment that might be part of a scherzo, and a final scrap of orchestral music again lasting roughly a minute. Sirén describes the music as "strange, powerful, and with daring, spicy harmonies—a step into the new even after Tapiola and the music for The Tempest".[41] Stearns gives a more detailed insight: "The first excerpt is classic Sibelian announcement of a first movement. There's a genteel orchestral thunderclap that throws open the door to a harmonic world that is Sibelius' alone, but has strange dissonances unlike any other work. Another glimpse sounds like the beginning of a scherzo, surprisingly spring-like with a buoyant flute solo. Another snippet has a classic Sibelian bassoon solo, the sort that speaks of primal things and goes to a dark, wintry underworld."[42]

Speculation

Richard Taruskin: Music in the Nineteenth Century (2010)[43]

Although only the first movement, copied by Voigt, is fully accepted as having been completed, the intended scale and general character of the Eighth Symphony may be inferred from several sources. Sibelius's correspondence with Voigt and with his binders, in 1933 and 1938 respectively, indicates the possibility of a notably large-scale work.[20] Apart from Nils-Eric Fougstedt's 1947 observation, there are also indications from Voigt that the work may have contained choral elements, along the lines of Beethoven's Ninth.[44]

From the available fragments of music, both Virtanen and Andrew Mellor of Gramophone detect hints of Tapiola, particularly in the first of the three extracts.[40][45] Kilpeläinen points to some of Sibelius's late minor works, in particular the "Five Esquisses" for piano Op. 114 (1929), as providing evidence that in his final compositional years Sibelius was "progressing towards a more abstract idiom: clear, ethereal images little touched by the human passions".[16] Further originality, Kilpeläinen says, is found in the "Surusoitto" music for organ, composed in 1931 for the funeral of Sibelius's friend Akseli Gallen-Kallela, a work that Aino Sibelius admitted might have been based on Eighth Symphony material: "Did the new symphony", asks Kilpeläinen, "thus also represent a modern sound unlike that of his previous style, with bleak, open tones and unresolved dissonances?"[16] After the recording of the fragments, Storgårds could recognise the composer's late style, adding that "the harmonies are so wild and the music so exciting that I'd really love to know how he went on with this."[41] Sibelius's only preserved comment on the music itself, as distinct from his occasional progress reports, is a remark to Schnéevoigt in December 1932: "You have no idea how clever it is".[23]

Scholars and critics are divided in their views about the value of the recovered excerpts. On the one hand, Josephson is convinced that sufficient material exists for a reconstruction of the entire symphony and eagerly awaits the undertaking of this task.[25] This view is echoed by Stearns: "[T]here's absolutely no reason not to attempt a completion".[42] Others, however, are more circumspect: Virtanen, in particular, emphasises that although the music is irrefutably late Sibelius, it has not been established beyond doubt that any of it belongs to the Eighth Symphony.[40] Sirén, who played a major role in organising the performance of the fragments, believes that completion is impossible on the basis of existing sketches,[41] and would be dependent on further discoveries.[45] He also surmises that Sibelius, having rejected the work, would not have relished hearing the fragments played, a viewpoint which McKenna endorses: "Watching the performance on YouTube, I could not help but think how disappointed the composer would have been to hear his unfinished music performed."[18] Reviewing the recorded excerpts in Gramophone, Andrew Mellor remarks that even if further manuscripts should come to light, the Sibelius Rights Holders would have full control over the material and would decide whether performance was appropriate. Mellor concludes: "We've had to wait some 80 years to hear less than three minutes of music, and the mystery of the Eighth isn't set to unfold any more rapidly from here".[45]

References

Citations

- Hepokoski, James. "Sibelius, 1865–89: early years". Grove Music Online. Retrieved 2 August 2013. (subscription required)

- Rickards, p. 22

- Sirén, Vesa; Hartikainen, Markku; Kilpeläinen, Kari; et al. "Studies in Helsinki 1885–1888". "Sibelius" website: Sibelius the Man. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- Rickards, pp. 50–51

- Rickards, pp. 68–69

- Barnett, p. 115

- Hepokoski, James. "Sibelius, 1898–1904: first international successes and local politics". Grove Music Online. Retrieved 2 August 2013. (subscription required)

- Hepokoski, James. "Sibelius, 1905–11: modern classicism". Grove Music Online. Retrieved 2 August 2013. (subscription required)

- Tawaststjerna, Sibelius: 1904–1914, p. 278

- Hepokoski, James. "Sibelius, 1912–26: late works". Grove Music Online. Retrieved 2 August 2013. (subscription required)

- Rickards, p. 12

- Rickards, p. 203

- Rickards, p. 171.

- Sibelius, Jean (2005). Dahlström, Fabian (ed.). Dagbok 1909–1944 [Diary 1909–1944]. Skrifter utgivna av Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, 681 (in Swedish). Helsingfors: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland. p. 327. ISBN 951-583-125-3. ISSN 0039-6842.

- Barnett, p. 309

- Kilpeläinen, Kari (October–December 1995). "Sibelius Eight: What happened to it?". Finnish Musical Quarterly (4). Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- Sirén, Vesa; Hartikainen, Markku; Kilpeläinen, Kari; et al. "Writing the eighth symphony 1928–1933". "Sibelius" website: Sibelius the Man. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- McKenna, Mark (November 2012). "Who Stopped the Music". The Monthly (84). Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- Ross 2008, p. 174

- Hepokoski, James. "Sibelius, 1927–57: the silence from Järvenpää". Grove Music Online. Retrieved 2 August 2013. (subscription required)

- Jackson and Murtomäki (eds), p. 19

- Stearns, David Patrick (3 January 2012). "One last Sibelius symphony after all?". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- "Jean Sibelius's own comments on his Eighth Symphony". Helsingin Sanomat (International Edition). 30 October 2011. Archived from the original on 21 November 2011. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- Ross 2008, p. 173

- Josephson, Nors (2004). "On Some Apparent Sketches for Sibelius's Eighth Symphony". Archiv für Musikwissenschaft. Franz Steiner Verlag (61): 54–67. ISSN 0003-9292. JSTOR 4145409.

- Sirén, Vesa; Hartikainen, Markku; Kilpeläinen, Kari; et al. "At the height of his popularity 1934–1939". "Sibelius" website: Sibelius the Man. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- Rickards, p. 185

- Sirén, Vesa; Hartikainen, Markku; Kilpeläinen, Kari; et al. "The war and the destruction of the eighth symphony 1939–1945". "Sibelius" website: Sibelius the Man. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- Levas, Santeri (1986). Jean Sibelius: Muistelma suuresta ihmisestä (in Finnish) (2nd ed.). Helsinki: WSOY. p. 391. ISBN 951-0-13306-X.

- Barnes, Julian (January–February 2012). "Where Sibelius Fell Silent". Intelligent Life. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- Rickards, p. 194

- Levas, Santeri: Jean Sibelius, p. 393.

- Sirén, Vesa; Hartikainen, Markku; Kilpeläinen, Kari; et al. "The silence of Ainola 1945–1957". Sibelius the Man. Sibelius. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- Botstein, Leon (14 August 2011). "The Transformative Paradoxes of Jean Sibelius". The Chronicle of Higher Education (online). Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- Sibelius, Jean: Dagbok 1909–1944, p. 328.

Ross, Alex (9 July 2007). "Apparition in the Woods". The New Yorker. Retrieved 12 June 2016. - Barnett, p. 352

- Schonberg, p. 96

- Service, Tom (20 September 2007). "The silence of Sibelius". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- Ross 2008, p. 176

- Virtanen, Timo (2011). "Jean Sibelius's Late Sketches and Orchestral Fragments" (PDF). BIS Records: Sibelius edition. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 April 2014. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- Sirén, Vesa (30 October 2011). "Is this the sound of Sibelius's lost Eighth Symphony?". Helsingin Sanomat (International Edition). Archived from the original on 22 January 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2016. (subscription required)

- Stearns, David Patrick (16 November 2011). "The Sibelius 8th: Can it be completed?". artsjournalblogs. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- Taruskin 2010, pp. 822–3

- Ross, p. 158

- Mellor, Andrew (17 November 2011). "Helsinki Philharmonic plays Sibelius' Eighth fragments". The Gramophone. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

Sources

- Barnett, Andrew (2007). Sibelius. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11159-0.

- Jackson, Timothy L.; Murtomäki, Veijo, eds. (2001). Sibelius Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-62416-9.

- Rickards, Guy (2008). Jean Sibelius. London: Phaidon Press. ISBN 978-0-7148-4776-4.

- Ross, Alex (2008). The Rest Is Noise. London: Fourth Estate. ISBN 978-1-84115-475-6.

- Schonberg, Harold C. (1970). The Lives of the Great Composers Vol. II. London: Futura Publications. ISBN 0-86007-723-3.

- Taruskin, Richard (2010). Music in the Nineteenth Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-538483-3.

- Tawaststjerna, Erik (1986). Sibelius: 1904–1914. Translated by Layton, Robert. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-520-05869-0.