T45 (classification)

T45 is disability sport classification in disability athletics for people with double above or below the elbow amputations, or a similar disability. The class includes people who are ISOD classes A5 and A7. The nature of the disability of people in this class can make them prone to overuse injuries. The classification process to be included in this class has four parts: a medical exam, observation during training, observation during competition and then being classified into this class.

_(Radebe).jpg.webp)

Definition

This classification is for disability athletics.[1] This classification is one of several classifications for athletes with ambulant related disabilities. Similar classifications are T40, T42, T43, T44, T45 and T46.[2] Jane Buckley, writing for the Sporting Wheelies, describes the athletes in this classification as: "Double above elbow or double below elbow amputations or similar disability."[1] The International Paralympic Committee defined this in 2011 as: "Athletes with BILATERAL upper limb impairment where BOTH limbs meet the relevant unilateral criteria described for upper limb deficiency (Section 4.1.4.b.i), impaired upper limb ROM (Section 4.1.5.c.i) or impaired upper limb muscle power (Section 4.1.6.c.i) may compete in this class for all running and jumping events."[3] The International Paralympic Committee defined this classification on their website in July 2016 as, "Upper limb/s affected by limb deficiency, impaired muscle power or impaired range of movement".[4]

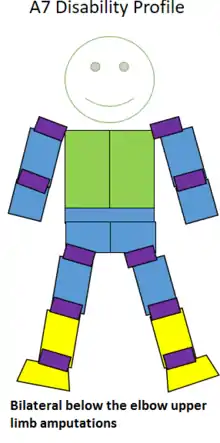

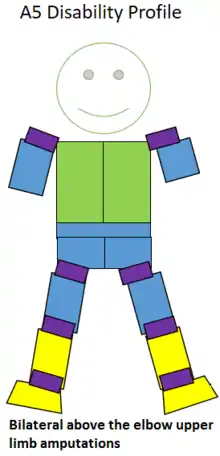

This class includes people from the ISOD A5 and A7 classes.[5][6]

Disability groups

Amputees

For A5 and A7 competitors in this class, the nature of a person's amputations in this class can effect their physiology and sports performance. Because they are missing a limb, amputees are more prone to overuse injuries in their remaining limbs. Common problems for intact upper limbs for people in this class include rotator cuffs tearing, shoulder impingement, epicondylitis and peripheral nerve entrapment.[7]

A study of was done comparing the performance of athletics competitors at the 1984 Summer Paralympics. It found there was no significant difference in performance in times between women in A6, A7 and A8 in the discus, women in A6, A7 and A8 in the shot put, women in the A6, A7 and A8 in the long jump, women in A6, A7 and A8 in the 100 meter race, women in A5, A6, A7 and A8 in the 100 meter race, men in the A3, A4, A5, A6, A7, A8 and A9 in the discus, men in A6, A7 and A8 in the discus, men in A1, A2, A3, A4, A5, A6, A7, A8 and A9 in the javelin, men in A6, A7 and A8 in the javelin, men in A6, A7 and A8 in the high jump, men in A5, A6 and A7 in the long jump, men in A6, A7 and A8 in the long jump, men in A6, A7 and A8 in the 100 meter race, men in A5, A6 and A7 in the 100 meter race, men in A6 and A7 in the 400 meter race, men in A5, A6 and A7 in the 400 meter race, men in A7 and A8 in the 400 meter race, men in A6 and A7 in the 1,500 meter race, and men in A7 and A8 in the 1,500 meter race.[8]

Performance and rules

People in this class are not required to use a starting block. They have an option to start from a standing position, a crouch or a 3 point stance. In relay events involving T40s classes, no baton is used. Instead, a handoff takes place via touch in the exchange zone.[9]

People with arm amputations in this class can have elevated padded blocks to place their stumps on for the start of the race. These blocks need to be in a neutral color or a color similar to that of the track, and they must be placed entirely behind the starting line. Their location needs to be such that they do not interfere with the start of any other athlete.[9]

In field events for this class, athletes are not required to wear a prosthetic. In jumping events, athletes have 60 seconds during which they must complete their jump. During this time, they can adjust their prosthetic.[9] If during a jump, the athlete's prosthesis falls off, the jump length start should start from where the takeoff board and the distance is where the prosthesis fell off. If prosthesis falls off outside the landing zone nearer the board than where athlete landed, the jump counts as a foul.[9]

History

The classification was created by the International Paralympic Committee and has roots in a 2003 attempt to address "the overall objective to support and co-ordinate the ongoing development of accurate, reliable, consistent and credible sport focused classification systems and their implementation."[10]

For the 2016 Summer Paralympics in Rio, the International Paralympic Committee had a zero classification at the Games policy. This policy was put into place in 2014, with the goal of avoiding last minute changes in classes that would negatively impact athlete training preparations. All competitors needed to be internationally classified with their classification status confirmed prior to the Games, with exceptions to this policy being dealt with on a case by case basis.[11] In case there was a need for classification or reclassification at the Games despite best efforts otherwise, athletics classification was scheduled for September 4 and September 5 at Olympic Stadium. For sportspeople with physical or intellectual disabilities going through classification or reclassification in Rio, their in competition observation event is their first appearance in competition at the Games.[11]

Becoming classified

Classification is often based on the anatomical nature of the amputation.[12][13] The classification system takes several things into account when putting people into this class. These includes which limbs are effected, how many limbs are effected, and how much of a limb is missing.[14][15]

For this class, classification generally has four phase. The first stage of classification is a health examination. For amputees, this is often done on site at a sports training facility or competition. The second stage is observation in practice, the third stage is observation in competition and the last stage is assigning the sportsperson to a relevant class.[16] Sometimes the health examination may not be done on site because the nature of the amputation could cause not physically visible alterations to the body.[17] During the training portion of classification, observation may include being asked to demonstrate their skills in athletics, such as running, jumping or throwing. A determination is then made as to what classification an athlete should compete in. Classifications may be Confirmed or Review status. For athletes who do not have access to a full classification panel, Provisional classification is available; this is a temporary Review classification, considered an indication of class only, and generally used only in lower levels of competition.[18]

Competitors

Notable runners in this class include Yohansson Nascimento (BRA), who holds T45 world records at 100m, 200m and 400m distances. 2012 Paralympic medalists Zhao Xu (CHN) and Samkelo Radebe (RSA) also compete in this class.[19][20]

References

- Buckley, Jane (2011). "Understanding Classification: A Guide to the Classification Systems used in Paralympic Sports". Archived from the original on 11 April 2011. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- "Summer Sports » Athletics". Australia: Australian Paralympic Committee. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- Tweedy, Sean (16 July 2010). "Research Report - IPC Athletics Classification Project for Physical Impairments" (PDF). Queensland, Australia: International Paralympic Committee. p. 43. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 May 2012. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- "IPC Athletics Classification & Categories". www.paralympic.org. Retrieved 2016-07-22.

- "CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM FOR STUDENTS WITH A DISABILITY". Queensland Sport. Queensland Sport. Archived from the original on April 4, 2015. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- "Classification 101". Blaze Sports. Blaze Sports. June 2012. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- Miller, Mark D.; Thompson, Stephen R. (2014-04-04). DeLee & Drez's Orthopaedic Sports Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9781455742219.

- van Eijsden-Besseling, M. D. F. (1985). "The (Non)sense of the Present-Day Classification System of Sports for the Disabled, Regarding Paralysed and Amputee Athletes". Paraplegia. International Medical Society of Paraplegia. 23. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- "PARALYMPIC TRACK & FIELD: Officials Training" (PDF). USOC. United States Olympic Committee. December 11, 2013. Retrieved August 6, 2016.

- "Paralympic Classification Today". International Paralympic Committee. 22 April 2010. p. 3. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - "Rio 2016 Classification Guide" (PDF). International Paralympic Committee. International Paralympic Committee. March 2016. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- Pasquina, Paul F.; Cooper, Rory A. (2009-01-01). Care of the Combat Amputee. Government Printing Office. ISBN 9780160840777.

- DeLisa, Joel A.; Gans, Bruce M.; Walsh, Nicholas E. (2005-01-01). Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation: Principles and Practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780781741309.

- Tweedy, Sean M. (2002). "Taxonomic Theory and the ICF: Foundations for a Unified Disability Athletics Classification" (PDF). Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly. 19 (2): 220–237. doi:10.1123/apaq.19.2.220. PMID 28195770. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-08-17. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- International Sports Organization for the Disabled. (1993). Handbook. Newmarket, ON: Author. Available Federacion Espanola de Deportes de Minusvalidos Fisicos, c/- Ferraz, 16 Bajo, 28008 Madrid, Spain.

- Tweedy, Sean M.; Beckman, Emma M.; Connick, Mark J. (August 2014). "Paralympic Classification: Conceptual Basis, Current Methods, and Research Update". Paralympic Sports Medicine and Science. 6 (85). Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- Gilbert, Keith; Schantz, Otto J.; Schantz, Otto (2008-01-01). The Paralympic Games: Empowerment Or Side Show?. Meyer & Meyer Verlag. ISBN 9781841262659.

- "CLASSIFICATION Information for Athletes" (PDF). Sydney Australia: Australian Paralympic Committee. 2 July 2010. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- Samkelo Radebe, retrieved 22 September 2012

- "Xu Zhao". London 2012 Paralympics. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

.svg.png.webp)