Takalik Abaj

Tak'alik Ab'aj (/tɑːkəˈliːk əˈbɑː/; Mayan pronunciation: [takˀaˈlik aˀ'ɓaχ] (![]() listen); Spanish: [takaˈlik aˈβax]) is a pre-Columbian archaeological site in Guatemala. It was formerly known as Abaj Takalik; its ancient name may have been Kooja. It is one of several Mesoamerican sites with both Olmec and Maya features. The site flourished in the Preclassic and Classic periods, from the 9th century BC through to at least the 10th century AD, and was an important centre of commerce,[3] trading with Kaminaljuyu and Chocolá. Investigations have revealed that it is one of the largest sites with sculptured monuments on the Pacific coastal plain.[4] Olmec-style sculptures include a possible colossal head, petroglyphs and others.[5] The site has one of the greatest concentrations of Olmec-style sculpture outside of the Gulf of Mexico.[5]

listen); Spanish: [takaˈlik aˈβax]) is a pre-Columbian archaeological site in Guatemala. It was formerly known as Abaj Takalik; its ancient name may have been Kooja. It is one of several Mesoamerican sites with both Olmec and Maya features. The site flourished in the Preclassic and Classic periods, from the 9th century BC through to at least the 10th century AD, and was an important centre of commerce,[3] trading with Kaminaljuyu and Chocolá. Investigations have revealed that it is one of the largest sites with sculptured monuments on the Pacific coastal plain.[4] Olmec-style sculptures include a possible colossal head, petroglyphs and others.[5] The site has one of the greatest concentrations of Olmec-style sculpture outside of the Gulf of Mexico.[5]

| |

Location within Mesoamerica | |

| Location | El Asintal, Retalhuleu Department, Guatemala |

|---|---|

| Region | Retalhuleu Department |

| Coordinates | 14°38′10.50″N 91°44′0.14″W |

| History | |

| Founded | Middle Preclassic |

| Cultures | Olmec, Maya |

| Events | Conquered by: Teotihuacan, K'iche' |

| Site notes | |

| Archaeologists | Miguel Orrego Corzo; Marion Popenoe de Hatch; Christa Schieber de Lavarreda; Claudia Wolley Schwarz |

| Architecture | |

| Architectural styles | Olmec, Early Maya |

| Responsible body: Ministerio de Cultura y Deportes / Proyecto Nacional Tak'alik Ab'aj | |

Takalik Abaj is representative of the first blossoming of Maya culture that had occurred by about 400 BC.[6] The site includes a Maya royal tomb and examples of Maya hieroglyphic inscriptions that are among the earliest from the Maya region. Excavation is continuing at the site; the monumental architecture and persistent tradition of sculpture in a variety of styles suggest the site was of some importance.[7]

Finds from the site indicate contact with the distant metropolis of Teotihuacan in the Valley of Mexico and imply that Takalik Abaj was conquered by it or its allies.[8] Takalik Abaj was linked to long-distance Maya trade routes that shifted over time but allowed the city to participate in a trade network that included the Guatemalan highlands and the Pacific coastal plain from Mexico to El Salvador.

Takalik Abaj was a sizeable city with the principal architecture clustered into four main groups spread across nine terraces. While some of these were natural features, others were artificial constructions requiring an enormous investment in labour and materials.[9] The site featured a sophisticated water drainage system and a wealth of sculptured monuments.

Etymology

Tak'alik Ab'aj' means "standing stone" in the local K'iche' Maya language, combining the adjective tak'alik meaning "standing", and the noun abäj meaning "stone" or "rock".[10] It was initially named Abaj Takalik by the American archaeologist Suzanna Miles,[11] using Spanish word order. This was grammatically incorrect in K'iche';[12] the Guatemalan government has now officially corrected this to Tak'alik Ab'aj'. Anthropologist Ruud Van Akkeren has proposed that the ancient name of the city was Kooja, the name of one of the highest-ranking elite lineages of the Mam Maya; Kooja means "Moon halo".[13]

Location

The site lies in the southwest of Guatemala, about 45 km (28 mi) from the border with the Mexican state of Chiapas and 40 km (25 mi) from the Pacific Ocean.[16]

Takalik Abaj is located in the north of the municipality of El Asintal, in the extreme north of Retalhuleu department, some 120 miles (190 km) from Guatemala City.[17] The site lies among five coffee plantations in the lower foothills of the Sierra Madre mountains; the Santa Margarita, San Isidro Piedra Parada, Buenos Aires, San Elías and Dolores plantations.[18] Takalik Abaj sits upon a ridge running north–south, descending in a southwards direction.[19] This ridge is bordered on the west by the Nimá River and on the east by the Ixchayá River, both flowing down from the Guatemalan Highlands.[20] The Ixchayá flows in a deep ravine but a suitable crossing point is located near to the site. The situation of Takalik Abaj at this crossing point was probably important in the founding of the city, since this channeled important trade routes through the site and controlled access to them.[21]

Takalik Abaj sits at an altitude of approximately 600 metres (2,000 ft) above sea level in an ecoregion classed as subtropical moist forest.[23] The temperature normally varies between 21 and 25 °C (70 and 77 °F) and the potential evapotranspiration ratio averages 0.45.[24] The area receives high annual rainfall, varying between 2,136 and 4,372 millimetres (84 and 172 in), with an average annual rainfall of 3,284 millimetres (129 in).[25] Local vegetation includes the Pascua de Montaña (Pogonopus speciosus), Chichique (Aspidosperma megalocarpon), Tepecaulote (Luehea speciosa), Caulote or West Indian Elm (Guazuma ulmifolia), Hormigo (Platymiscium dimorphandrum), Mexican Cedar (Cedrela odorata), Breadnut (Brosimum alicastrum), Tamarind (Tamarindus indica) and Papaturria (Coccoloba montana).[26]

A road, denominated 6W, passes the site running 30 kilometres (19 mi) from the town of Retalhuleu to Colomba Costa Cuca in the department of Quetzaltenango.[18]

Takalik Abaj is located at an approximate distance of 100 kilometres (62 mi) from the contemporary archaeological site of Monte Alto, 130 km (81 mi) from Kaminaljuyu and 60 kilometres (37 mi) from Izapa in Mexico.[16]

Ethnicity

The changing styles of architecture and iconography at Takalik Abaj suggest that the site has been occupied by changing ethnic groups. The archaeological finds of the Middle Preclassic period suggest that the population of Takalik Abaj may have been affiliated with the Olmec culture of the Gulf Coast lowlands region who are thought to have been speakers of a Mixe–Zoquean language.[21] In the Late Preclassic period, Olmec art styles were exchanged for Maya styles and presumably this shift was accompanied by an influx of ethnic Maya, speaking a Mayan language.[27] There are some hints from the indigenous chronicles that the inhabitants of the site may have been the Yoc Cancheb, a branch of the Mam Maya.[27] The Kooja lineage of the Mam, an ancient noble line, may have had a Classic Period origin in Takalik Abaj.[28]

Economy and trade

Takalik Abaj was one of a series of early sites on or near the Pacific coastal plain that were important commercial, ceremonial and political centres. It is apparent that it prospered from the production of cacao and from the trade routes that crossed the region.[29] At the time of the Spanish Conquest in the 16th century the area was still important for its cacao production.[30]

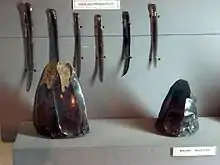

Study of obsidian recovered at Takalik Abaj indicates that the majority originated from the El Chayal and San Martín Jilotepeque sources in the Guatemalan highlands. Lesser quantities of obsidian originated from other sources such as Tajumulco, Ixtepeque and Pachuca.[31] Obsidian is a natural volcanic glass that was used across Mesoamerica to make durable tools and weapons including knives, spearheads, arrowheads, bloodletters for ritual autosacrifice, prismatic blades for woodwork and many other day-to-day tools. The use of obsidian by the Maya has been likened to steel use in the modern world and it was widely traded throughout the Maya region and beyond.[32] The proportion of obsidian from different sources varied over time:

| Period | Date | No. of artifacts | El Chayal % | San Martín Jilotepeque % | Pachuca % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Preclassic | 1000–800 BC | 151 | 33.7 | 52.3 | – |

| Middle Preclassic | 800–300 BC | 880 | 48.6 | 39 | – |

| Late Preclassic | 300 BC – AD 250 | 1848 | 54.3 | 32.5 | – |

| Early Classic | AD 250–600 | 163 | 50.9 | 35.5 | – |

| Late Classic | AD 600–900 | 419 | 41.7 | 45.1 | 1.19 |

| Postclassic | AD 900–1524 | 605 | 39.3 | 43.4 | 4.2 |

History

|

| Maya civilization |

|---|

| History |

| Preclassic Maya |

| Classic Maya collapse |

| Spanish conquest of the Maya |

The site had a long and continuous settlement history, with the period of principal occupation stretching from the Middle Preclassic down to the Postclassic. The earliest known occupation at Takalik Abaj dates towards the end of the Early Preclassic, ca. 1000 BC. However, it was not until the Middle to Late Preclassic that its first real florescence began with a noted surge in architectural constructions.[19] From this period onwards a continuity of culture and population settlement is in evidence, as represented by the persistence of a local ceramic style (called Ocosito) that remained in use until the Late Classic. The Ocosito style was typically made with red paste and pumice and extended westwards at least as far as Coatepeque, southwards to the Ocosito River and eastwards to the Samalá River. By the Terminal Classic, pottery associated with a highland K'iche' ceramic style had begun to appear intermixed with Ocosito ceramic complex deposits. Ocosito ceramics were replaced entirely by the K'iche' ceramic tradition by the Early Postclassic period.[33]

| Period | Division | Dates | Summary | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preclassic | Early Preclassic | 1000–800 BC | Diffuse population | |

| Middle Preclassic | 800–300 BC | Olmec | ||

| Late Preclassic | 300 BC – AD 200 | Early Maya | ||

| Classic | Early Classic | AD 200–600 | Teotihuacan-linked conquest | |

| Late Classic | Late Classic | AD 600–900 | Local recovery | |

| Terminal Classic | AD 800–900 | |||

| Postclassic | Early Postclassic | AD 900–1200 | K'iche' occupation | |

| Late Postclassic | AD 1200–1524 | Abandonment | ||

| Note: The period spans used at Takalik Abaj differ slightly from those generally used in the standard chronology applied to the wider Mesoamerican region. | ||||

Early Preclassic

Takalik Abaj was first occupied at the end of the Early Preclassic period.[34] The remains of an Early Preclassic residential area have been found to the west of the Central Group, on the bank of the El Chorro stream. These first houses were built with floors made from river cobbles and reed-thatched roofs supported on timber poles.[35] Pollen analysis has revealed that the first inhabitants entered the area when it was still thick forest, which they began to clear in order to cultivate maize and other plants.[36] Over 150 pieces of obsidian have been recovered from this area, known as El Escondite, mostly originating from the San Martín Jilotepeque and El Chayal sources.[31]

Middle Preclassic

Takalik Abaj was reoccupied at the beginning of the Middle Preclassic.[19] This was probably by Mixe–Zoquean inhabitants, as evidenced by the plentiful Olmec-style sculpture at the site dating to this period.[21] The construction of public architecture had probably begun by the Middle Preclassic;[5] the earliest structures were made of clay, which was sometimes partially burned in order to harden it.[19] Ceramics from this period belonged to the local Ocosito tradition.[5] This ceramic tradition, although it was local, showed strong affinities with the ceramics of the coastal plain and foothills of the Escuintla region.[21]

The Pink Structure (Estructura Rosada in Spanish) was built as a low platform during the first part of the Middle Preclassic, at a time when the city was producing Olmec-style sculpture and La Venta was flourishing on the Gulf coast of Mexico (c.800–700 BC).[37] During the latter part of the Middle Preclassic (c.700–400 BC), the Pink Structure was buried under the first version of the enormous Structure 7.[37] It was at this time that the use of Olmec ceremonial structures was discontinued and Olmec sculpture was destroyed, signalling an intermediate period prior to the beginning of the city's Early Maya phase.[37] The transition between the two phases was a gradual one, without abrupt changes.[38]

Late Preclassic

During the Late Preclassic (300 BC – AD 200) various sites in the Pacific coastal region developed into true cities; Takalik Abaj was one of these, with an area greater than 4 square kilometres (1.5 sq mi).[40] The cessation of Olmec influence upon the Pacific coastal zone occurred at the beginning of the Late Preclassic.[21] At this time Takalik Abaj emerged as an important centre with an apparently local style of art and architecture;[41] the inhabitants began to make boulder sculptures and to erect stelae and associated altars.[42] At this time, between 200 BC and 150 AD, Structure 7 reached its maximum dimensions.[37] Monuments were erected with both political and religious significance, some of which bore Maya-style dates and depictions of rulers.[43] These early Maya monuments are carved with what may be among the earliest Maya hieroglyphic inscriptions and use of the Mesoamerican Long Count calendar.[44] The early dates on Stelae 2 and 5 allow this style of sculpture to be more securely fixed in time within the late 1st century to the early 2nd century AD.[37] The so-called potbelly style of sculpture also appeared at this time.[44] The appearance of Maya sculpture and the cessation of Olmec-style sculpture may represent a Maya intrusion into the area previously occupied by Mixe–Zoquean inhabitants.[44] One possibility holds that Maya elites entered the area in order to take control of the cacao trade.[44] However, given the evident continuity in local ceramic styles from the Middle to Late Preclassic, the change in attributes from Olmec to Maya may have been more an ideological than a physical transition.[44] If they had arrived from elsewhere, the finds of Maya stelae and a Maya royal tomb suggest that the Maya were in a dominant position, whether they arrived as traders or conquerors.[45]

There is evidence of increasing contact with Kaminaljuyu, which emerged as a principal centre at this time, linking the Pacific coastal trade routes with the Motagua River route, as well as increased contact with other sites along the Pacific coast.[46] Within this extended trade route, Takalik Abaj and Kaminaljuyu appear to have been the two principal foci.[21] The early Maya style of sculpture spread throughout this network.[47]

During the Late Preclassic structures were built using volcanic stone held together with clay, as in the Middle Preclassic.[19] However, they evolved to include stepped structures with indented corners and stairways dressed with rounded pebbles.[47] At the same time, old Olmec-style sculptures were moved from their original positions and placed in front of the new-style buildings, sometimes reusing sculpture fragments in the stone facing.[37]

Although the Ocosito ceramic tradition continued in use,[47] the Late Preclassic ceramics in Takalik Abaj were strongly related to the Miraflores Ceramic Sphere that included Escuintla, the Valley of Guatemala and western El Salvador.[21] This ceramic tradition consists of fine red wares that are particularly associated with Kaminaljuyu and are found throughout the southeastern Guatemalan highlands and the adjacent Pacific slope.[48]

Early Classic

In the Early Classic, from around the 2nd century AD, the stela style that developed at Takalik Abaj and was associated with the portrayal of historic figures was adopted across the Maya lowlands, particularly in the Petén Basin.[49] During this period some of the pre-existing monuments were deliberately destroyed.[50]

In this period, the ceramics showed a change with the entry of the highland Solano style,[51] This ceramic tradition is most associated with the Solano site in the southeastern Valley of Guatemala and the most characteristic type is a brick-red ware covered with a bright orange micaceous slip, sometimes painted with pink or purple decoration.[52] This style of ceramics has been associated with the highland K'iche' Maya.[27] These new ceramics did not replace the pre-existing Ocosito complex but rather became mingled with them.[51]

Archaeological investigations have shown that the destruction of monuments and interruption of new construction at the site occurred simultaneously with the arrival of so-called Naranjo style ceramics, which appear to be linked to styles from the great metropolis of Teotihuacan in the distant Valley of Mexico.[51] The Naranjo ceramic tradition is particularly characteristic of the western Pacific coast of Guatemala between the Suchiate and Nahualate rivers. The most common forms are pitchers and bowls with a surface that has been smoothed with a cloth, leaving parallel marks, and usually coated with a white or yellow wash.[53] At the same time, the use of local Ocosito ceramics waned. This Teotihuacan influence places the destruction of monuments in the second half of the Early Classic.[51] The presence of the conquerors linked to the Naranjo-style ceramics was not of long duration and suggests that the conquerors exerted long-distance control of the site, replacing the local rulers with their own governors while leaving the local population intact.[8]

The conquest of Takalik Abaj broke the ancient trade routes running along the Pacific coast from Mexico to El Salvador, these were replaced by a new route running up the Sierra Madre and into the northwestern Guatemalan highlands.[54]

Late Classic

In the Late Classic the site appears to have recovered from its earlier defeat. Naranjo-style ceramics diminished greatly in quantity and there was a surge in new large-scale construction. Many monuments broken by the conquerors were re-erected at this time.[56]

Postclassic

Although use of the local Ocosito-style ceramics continued, there was a marked intrusion of K'iche' ceramics from the highlands in the Postclassic period, concentrated particularly in the northern part of the site but extending to cover the whole.[57] The indigenous accounts of the K'iche' themselves claim that they conquered this region of the Pacific coast, suggesting that the presence of their ceramics is associated with their conquest of Takalik Abaj.[56]

The K'iche' conquest appears to have taken place around AD 1000, some four centuries earlier than had been supposed using calculations based on the indigenous accounts.[58] After the initial arrival of the K'iche' activity continued at the site without pause, and the local styles were simply replaced by styles associated with the conquerors.[59] This suggests that the original inhabitants abandoned the city they had occupied for almost two millennia.[1]

Modern history

The first published account appeared in 1888, written by Gustav Bruhl.[60] The German ethnologist and naturalist Karl Sapper described Stela 1 in 1894 after he saw it beside the road he was travelling.[60] Max Vollmberg, a German artist, drew Stela 1 and noted some other monuments, which attracted the interest of Walter Lehmann.[60]

In 1902 the eruption of the nearby Santiaguito volcano covered the site in a layer of volcanic ash that varies between 40 and 50 centimetres (16 and 20 in) thick.[61]

Walter Lehmann began the study of the sculptures of Takalik Abaj in the 1920s. In January 1942 J. Eric S. Thompson visited the site with Ralph L. Roys and William Webb on behalf of the Carnegie Institution while undertaking a study of the Pacific Coast,[12] publishing his accounts in 1943. Further investigations were undertaken by Suzanna Miles, Lee Parsons and Edwin M. Shook. Miles bestowed the name Abaj Takalik to the site, which appeared in her contributed chapter in volume 2 of the Handbook of Middle American Indians published 1965. Previously it had been known by various names, including San Isidro Piedra Parada and Santa Margarita, after the names of the plantations in which the site lies, and also by the name of Colomba, a village to the north in the department of Quetzaltenango.[60]

Excavations at the site in the 1970s were sponsored by the University of California, Berkeley. They began in 1976 and were undertaken by John A. Graham, Robert F. Heizer and Edwin M. Shook.[60] This first season uncovered 40 new monuments, including Stela 5, to add to the dozen or so already known.[60] Excavations by the University of California at Berkeley continued until 1981 and uncovered even more monuments in that time.[60] From 1987 excavations have been continued by the Guatemalan Instituto de Antropología e Historia (IDAEH) under the direction of Miguel Orrego and Christa Schieber, and new monuments continue to be uncovered.[60] The site has been declared a national park.

In 2002 Takalik Abaj was entered on the UNESCO World Heritage Tentative Lists, under the heading of "The Mayan-Olmecan Encounter".[62]

Site description and layout

The core of the site covers about 6.5 square kilometres (2.5 sq mi)[64] and includes remains of some 70 monumental structures positioned around a dozen plazas.[64][65] Takalik Abaj has 2 ballcourts and over 239 known stone monuments,[64] including impressive stelae and altars. The granite used to make monuments in Olmec and early Maya styles is much different from the soft limestone used in the Petén cities.[66] The site is also noted for its hydraulic systems, including a temazcal or sauna bath with a subterranean drainage, and Preclassic tombs found in excavations from the late 1990s onwards by Drs. Marion Popenoe de Hatch, Christa Schieber de Lavarreda and Miguel Orrego, from the Ministerio de Cultura y Deportes.

The structures at Takalik Abaj are spread among four groups; the Central, North and West Groups are clustered together but the South Group is located about 5 km (3.1 mi) to the south.[19] The site is naturally defensible, being bordered by steep ravines.[65] The site is spread over a series of nine terraces, which vary in width from 140 to 220 metres (460 to 720 ft) and have faces varying in height from 4.6 to 9.4 metres (15 to 31 ft).[65] These terraces are not uniformly oriented, instead the direction of their retaining faces depends upon the lie of the local terrain.[65] The three main terraces supporting the city are artificial, with over 10 metres (33 ft) of fill being used in places.[44]

When Takalik Abaj was at its greatest extent, major architecture in the city covered an area of approximately 2 by 4 kilometres (1.2 by 2.5 mi), although the area occupied by residential construction has not been determined.[44]

- The Central Group occupies Terraces 1 to 5, which were artificially levelled. The group contains 39 structures arranged around plazas that are open on the north and south sides. The Central Group was first occupied in the Middle Preclassic and contains a concentration of more than 100 stone monuments.[67][68][69]

- The West Group consists of 21 structures on Terrace 6, which was also artificially levelled. The structures are arranged around plazas that were left open on the east side. Seven monuments have been found in this group. The West Group is bordered by the rivers Nima on the west and the San Isidro on the east. A notable find in the West Group was the discovery of some jade masks there. The West Group was occupied from the Late Preclassic through to at least the Late Classic.[70]

- The North Group was occupied from the Terminal Classic through to the Postclassic.[71] This group's structures were built using a different method from those in the Central Group, and were made out of compacted clay without stone construction or facing.[67] The group occupies Terraces 7 through 9, which follow the contours of the natural terracing present and show no evidence of significant artificial levelling.[67] In combination with a noted absence of sculptured monuments, the different construction methods and ceramic assemblages associated with this group imply an occupation of the North Group by a new settlement community who arrived in the Late Classic period, most probably K'iche' Maya from the highlands.[67]

- The South Group is located outside the site core, some 0.5 kilometres (0.31 mi) south of the Central Group, about 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) west of El Asintal, it consists of 13 structure mounds forming a dispersed group.[72]

Water control

The hydraulic system included stone canals, which were not used for irrigation but rather to channel runoff and maintain the structural integrity of the principal architecture.[44] These channels were also used to carry water to the residential areas of the city,[73] and it is possible that the channels also served a ritual purpose linked to the rain god.[63] So far, the remains of 25 channels have been found at the site.[74] The larger channels measure 0.25 metres (10 in) wide by 0.30 metres (12 in) high, secondary channels measure about half that.[75]

There are two methods of construction used for the water channels. Clay channels date from the Middle Preclassic while stone-lined channels date from the Late Preclassic through to the Classic, with stone-lined channels from the Late Classic being the largest channels built at the site. It is presumed that the clay channels were not sufficiently effective, thus leading to the switch in construction materials and the implementation of stone-lined channels. In the Late Classic pieces of broken stone monuments were reused in the construction of the water channels.[76]

Terraces

Terrace 2 is in the Central Group.[68] Structures on this terrace date as far back as the Middle Preclassic and include an early example of a ballcourt.[22]

Terrace 3 is in the Central Group.[68] The facade represented a major construction project and dates to the Late Preclassic.[2] The southeastern portion of Terrace 3 is believed to have been the most sacred plaza in the city, based on its concentration of sculpture and especially upon the presence of Structure 7 on the east side of the plaza.[77] This area of the ancient city has been called Tanmi T'nam ("Heart of the People" in Mam Maya) by the mayor of El Asintal.[77] A north-south row of 5 monuments was erected at the base of Structure 8, on the southwest side of the plaza, and another row of 5 sculptures runs east–west parallel to the southern edge of the terrace, with an additional 2 sculptures slightly south of them.[77]

Terrace 5 is on the eastern side of the site immediately to the north of the Central Group. It measures 200 metres (660 ft) east to west and 300 metres (980 ft) north to south. Terrace 5 is on the San Isidro Piedra Parada plantation and is currently used for the cultivation of coffee. The retaining face of the terrace was built of compacted clay during the Late Preclassic and represented an enormous inversion of labour. This terrace continued in use until the Postclassic.[78]

Terrace 6 supports the 16 structures of the West Group. It measures 150 metres (490 ft) from east to west and 140 metres (460 ft) from north to south. The terrace shows various phases of construction, it overlies a substructure built from large worked blocks of basalt, which dates to the Late Preclassic, later phases of construction date to the Late Classic and the terrace has traces of the Postclassic K'iche' occupation of the site. The terrace lies within the San Isidro Piedra Parada and Buenos Aires plantations and the land is currently dedicated to the cultivation of rubber and coffee. A modern road cuts the eastern corner of Terrace 6.[79]

Terrace 7 is a natural terrace that supports a part of the North Group. It runs east–west and is 475 metres (1,558 ft) long. It supports 15 structures dating from the Terminal Classic through to the Postclassic and associated with the K'iche' occupation of the site. This terrace lies between the Buenos Aires and San Elías plantations and the eastern part has been cut by a modern road.[67]

Terrace 8 is another natural terrace in the North Group. It also runs east west and is 400 metres (1,300 ft) long. A modern road has cut the eastern part of the terrace and the western side of Structure 46 upon its edge. The terrace supports only this structure and one other to the north (Structure 54). The terrace was probably a residential area with cultivated land associated with the North Group. This terrace is associated with the K'iche' occupation of the site from the Terminal Classic through to the Postclassic.[67]

Terrace 9 is the largest terrace at Takalik Abaj and supports part of the North Group. It is approximately 400 metres (1,300 ft) running east–west and 300 metres (980 ft) from north to south. The retaining face of the terrace runs immediately to the north of the main North Group complex on the western half of Terrace 7 for 200 metres (660 ft), at the eastern extreme of this section it turns north above Terrace 8 for 300 metres (980 ft) before changing to run another 200 metres (660 ft) east, limiting Terrace 8 on its west and north sides. Terrace 9 supports only two major structures (Structures 66 and 67). A modern road cuts the eastern side of the Terrace 9, excavations where the road has cut the terrace have revealed the possible remains of a ballcourt.[80]

Structures

The Ballcourt is located in the southwest of Terrace 2 and dates to the Middle Preclassic. It has a north–south alignment with the sides of the 4.6-metre (15 ft) wide playing area formed by Structures Sub-2 and Sub-4. The ballcourt is just over 22 metres (72 ft) long with a playing area of 105 square metres (1,130 sq ft). The southern limit of the ballcourt is formed by Structure Sub-1, just over 11 metres (36 ft) to the south of Structures Sub-2 and Sub-4, creating a southern end-zone that runs east–west and measures 23 by 11 metres (75 by 36 ft) with a surface area of 264 square metres (2,840 sq ft).[22]

Structure 5 is a large pyramid on the west side of Terrace 3.[81] It was largely built during the Middle Preclassic.[81] It forms the western end of an alignment of three structures, the others being Structures 6 and 7.[81]

Structure 6 is a stepped rectangular platform forming the middle of the alignment on Terrace 3.[81] It was first built in the Middle Preclassic but reached is greatest extent during the Late Preclassic and the beginning of the Early Classic.[81] It is one of the most important ceremonial structures in the Central Group.[82]

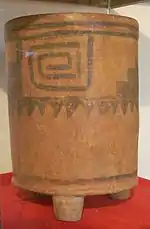

Structure 7 is a large platform located to the east of the plaza on Terrace 3 in the Central Group and is considered to have been one of the most sacred buildings at Takalik Abaj due to a series of important finds associated with it. Structure 7 measures 79 by 112 metres (259 by 367 ft) and dates to the Middle Preclassic,[83] although it did not attain its final form until the latter part of the Late Preclassic.[37] Built upon the northern part of Structure 7 are two smaller structures, designated as Structures 7A and 7B.[83] In the Late Classic, Structures 7, 7A and 7B were all refaced with stone.[84] Structure 7 supports three rows of monuments aligned north–south that may have served as an astronomical observatory.[85] One of these rows was aligned with the constellation Ursa Major in the Middle Preclassic, another aligned with Draco in the Late Preclassic, while the middle row was aligned with Structure 7A.[81] Another important find in Structure 7 was a Late Classic cylindrical incensario given the name "La Niña" by archaeologists due to its prominent female appliqué figure. It dates to the earliest levels of K'iche' occupation of the site and is 50 centimetres (20 in) high and 30 centimetres (12 in) wide at the base. It was found together with a large quantity of other offerings including further ceramics and fragments of broken sculptures.[86]

The Pink Structure (Estructura Rosada) was a small ceremonial platform built upon the central axis of Structure 7 before the latter was erected over it.[37] It is believed that this substructure was in use at the same time as Olmec sculpture was being produced both at Takalik Abaj and at La Venta in the Olmec heartland of Veracruz in Mexico.[37]

Structure 7A is a small structure sitting on top of the northern part of Structure 7. It dates to the Middle Preclassic and has been excavated. The Late Preclassic royal tomb known as Burial 1 was found in its centre. A large offering of hundreds of ceramic vessels was found in the base of the structure and is associated with the burial. Structure 7A underwent substantial rebuilding in the Early Classic and was again modified in the Late Classic.[87] Structure 7A measures 13 by 23 metres (43 by 75 ft) and stands almost 1 metre (3.3 ft) high.[38] Its four sides were dressed with standing stones surrounded by a pavement.[38]

Structure 7B is a small structure situated on the eastern side of Structure 7.[81] Like Structure 7A, the four sides were dressed with standing stones and were surrounded by a pavement.[38]

Structure 8 is located to the southwest of the plaza on Terrace 3, immediately to the west of the access stairway.[77] Five sculpted monuments were erected in a row at the base of the east side of the building; the four that have been excavated are Monument 30, Stela 34, Stela 35 and Altar 18.[77]

Structure 11 has been excavated. It was covered with rounded boulders held together with clay.[19] It is located to the west of the plaza in the southern area of the Central Group.[55]

Structure 12 lies to the east of Structure 11.[88] It has also been excavated and, like Structure 11, it is covered with rounded boulders held together with clay.[19] It lies to the east of the plaza in the southern area of the Central Group.[55] The structure is a three-tiered platform with stairways on the east and west sides. The visible remains date to the Early Classic but they overlie Late Preclassic construction. A row of sculptures lines the west side of the structure, including six monuments, a stela and an altar.[55] Further monuments line the east side, one of which may be the head of a crocodilian, the others are plain. Sculpture 69 is located on the south side of the structure.[88]

Structure 17 is located in the South Group, on the Santa Margarita plantation. It contained a Late Preclassic cache of 13 prismatic obsidian blades.[89]

Structure 32 is located near the western edge of the West Group.[90]

Structure 34 is in the West Group, at the eastern corner of Terrace 6.[91]

Structures 38, 39, 42 and 43 are joined by low platforms on the east side of a plaza on Terrace 7, aligned north–south. Structures 40, 47 and 48 are on south, west and north sides of this plaza. Structures 49, 50, 51, 52 and 53 form a small group on the west side of the terrace, bordered on the north by Terrace 9. Structure 42 is the tallest structure in the North Group, measuring about 11.5 metres (38 ft) high. All of these structures are mounds.[92]

Structure 46 is a mound at the edge of Terrace 8 in the North Group and dates from the Terminal Classic through to the Postclassic. The west side of the structure has been cut by a modern road.[67]

Structure 54 is built upon Terrace 8, to the north of Structure 46, in the North Group. It is surrounded by an open area without mounds that was probably a mixed residential and agricultural area. It dates from the Terminal Classic through to the Postclassic.[67]

Structure 57 is a large mound at the southern limit of the Central Group with an excellent view across the coastal plain. The structure was built in the Late Preclassic and underwent a second phase of construction in the Late Classic. It may have served as a look-out point.[51]

Structure 61, Mound 61A and Mound 61B are all on the east side of Terrace 5, on the San Isidro plantation. Structure 61 was built during the Early Classic and is dressed with stone, it was built upon an earlier construction dating to the Late Preclassic. Stela 68 was found at the base of Mound 61A near to a broken altar. Structure 61 and its associated mounds may have been used to control access to the city during the height of its power, Mound 61A was reused during the Postclassic occupation of the site. Early Classic finds from Mound 61A include four ceramic vessels and four obsidian prismatic blades.[93]

Structure 66 is located on Terrace 9, at the northern extreme of the North Group. It had an excellent view across the entire city and may have served as a sentry post controlling access to the site. It dates from the Terminal Classic through to the Postclassic.[94]

Structure 67 is a large platform on Terrace 9 that may have been associated with a possible residential area upon that terrace and located to the north of the North Group.[94]

Structure 68 is in the West Group. A part of the western side of the structure has been cut by a modern road. This has revealed a sequence of superimposed clay substructures dating to the Late Preclassic, the structure was then dressed with stone in the Early Classic.[91]

Structure 86 is to the west of Structure 32, at the western edge of the West Group. The first phase of construction dates to the Early Classic, between 150 and 300 AD, when it took the form of a sunken patio, with stairways descending in the middle of its perimeter walls.[90] At the centre of the patio were placed a clay altar and a stone, around which and across the rest of the patio were deposited an enormous number of offerings consisting of ceramic vessels, mostly from the Solano tradition.[95]

North Ballcourt. The possible remains of a second ballcourt were found to the north of the North Group and may have been associated with the occupation of that group from the Terminal Classic through to the Postclassic. It was built from compacted clay and runs east–west, the North Structure was 2 metres (6.6 ft) tall and the South Structure had a height of 1 metre (3.3 ft), the playing area was 10 metres (33 ft) wide.[94]

Stone monuments

As of 2006, 304 stone monuments have been found at Takalik Abaj, mostly carved from local andesite boulders.[96] Of these monuments 124 are carved with the remainder being plain; they are mostly found in the Central and Western Groups.[97] The worked monuments can be divided into four broad classifications: Olmec-style sculptures, which represent 21% of the total, Maya-style sculptures representing 42% of the monuments, potbelly monuments (14% of the total) and the local style of sculpture represented by zoomorphs (23% of the total).[98]

Most of the monuments at Takalik Abaj are not in their original positions but rather have been moved and reset at a later date, therefore the dating of monuments at the site often depends upon stylistic comparisons. An example is a series of four monuments found in a plaza in front of a Classic period platform, with at least two of the four (Altar 12 and Monument 23) dating to the Preclassic.

There are several stelae sculpted in the early Maya style that bear hieroglyphic texts with Long Count dates that place them in the Late Preclassic. This style of sculpture is ancestral to the Classic style of the Maya lowlands.

Takalik Abaj has various so-called Potbelly monuments representing obese human figures sculpted from large boulders, of a type found throughout the Pacific lowlands, extending from Izapa in Mexico to El Salvador. Their precise function is unknown but they appear to date from the Late Preclassic.[100]

Olmec style sculptures

The many Olmec-style sculptures, including Monument 23, a colossal head that was recarved into a niche figure,[101] seem to indicate a physical Olmec presence and control, possibly under an Olmec governor.[102] Archaeologist John Graham states that:

Olmec sculpture at Abaj Takalik such as Monument 23 clearly reflects the presence of Olmec sculptors who are working for Olmec patrons and creating Olmec art with Olmec content in the context of Olmec ritual.[103]

Others are less sure: the Olmec-style sculptures may simply imply a common iconography of power on the Pacific and Gulf coasts.[7] In any case, Takalik Abaj was certainly a place of importance for Olmecs.[104] The Olmec-style sculptures at Takalik Abaj all date to the Middle Preclassic.[98] Except for Monuments 1 and 64, the majority were not found in their original locations.[98]

Maya style sculptures

There are more than 30 monuments in the early Maya style, which dates to the Late Preclassic, making it the most common style represented at Takalik Abaj.[47] The great quantity of early Maya sculpture and the presence of early examples of Maya hieroglyphic writing suggest that the site played an important part in the development of Maya ideology.[47] The origins of the Maya sculptural style may have developed in the Preclassic on the Pacific coast and Takalik Abaj's position at the nexus of key trade routes could have been important in the dissemination of the style across the Maya area.[105] The early Maya style of monument at Takalik Abaj is closely linked to the style of monument at Kaminaljuyu, showing mutual influence. This interlinked style spread to other sites that formed part of the extended trade network of which these two cities were the twin foci.[47]

Potbelly style sculptures

Sculptures of the Potbelly style are found all along the Pacific Coast from southern Mexico to El Salvador, as well as further afield at sites in the Maya lowlands.[106] Although some investigators have suggested that this style is pre-Olmec, archaeological excavations on the Pacific Coast, including those at Takalik Abaj, have shown that this style began to be used at the end of the Middle Preclassic and reached its height during the Late Preclassic.[107] The potbelly sculptures at Takalik Abaj all date to the Late Preclassic and are very similar to those at Monte Alto in Escuintla and Kaminaljuyu in the Valley of Guatemala.[107] Potbelly sculptures are generally rough sculptures that show considerable variation in size and the position of the limbs.[107] They depict obese human figures, usually sat cross-legged with their arms upon their stomach. They have puffed out or hanging cheeks, closed eyes and are of indeterminate gender.[107]

Local style sculptures

Local style sculptures are generally boulders carved into zoomorphic shapes, including three-dimensional representations of frogs, toads and crocodilians.[108]

Olmec-Maya transition: El Cargador del Ancestro

The Cargador del Ancestro ("Ancestor Carrier") consists of four fragments of sculpture that had been reused in the facades of four different buildings during the latter part of the Late Preclassic.[81] Monuments 215 and 217 were discovered in 2008 during excavations of Structure 7A, while Stela Fragments 53 and 61 had been unearthed in previous excavations.[110] Archaeologists discovered that although Monuments 215 and 217 possessed different themes and were executed in differing styles, they in fact fitted together perfectly to form part of a single sculpture that was still incomplete.[38] This prompted a revision of previously found sculpture fragments and resulted in the discovery of two further pieces, originally found in Structures 12 and 74.[38]

The four pieces were found to make up a single monumental 2.3-metre (7.5 ft) high column with an unusual combination of sculptural characteristics.[111] The extreme upper and lower portions are damaged and incomplete and the sculpture comprises three sections.[112] The lowest section is a rectangular column with an early hieroglyphic text on both faces and a richly dressed Early Maya figure on the front.[112] The figure is wearing a headdress in the form of a crocodile or crocodile-feline hybrid with the jaws agape and the face of an ancestor emerging.[112] The lower portion of this section is damaged and a part of both the text and the figure is missing.[112]

The middle section of the column, forming a type of capital, is a high-relief sculpture of the head of a bat executed in the curved lines of the Maya style, with small eyes and eyebrows formed by two small volutes.[112] The leaf-shaped nose is characteristic of the Common Vampire Bat (Desmodus rotundus).[112] The mouth is open, exposing the partly preserved fangs, and a prominent tongue extends downwards.[112] A band of double triangles runs around the sculpture with a carved cord or rope and may symbolise the bat's wings.[112]

The upper section of the column is the sculpted figure of a squat, bare-footed individual standing upon the bat's head.[113] The figure wears a loincloth bound by a belt and decorated with a large U symbol.[112] An elaborately carved chest ornament with interlace pattern descends from the neck across the waste.[112] The style is somewhat rigid and is reminiscent of formal olmec sculpture, and various costume elements resemble those found on Olmec sculptures from the Gulf Coast of Mexico.[112] The figure has oval eyes and large earspools, the nose and mouth of the figure are damaged.[112] It wears two bands that cross on the back and are joined to the belt and the shoulders, they support a small human figure facing backwards.[112] The position and characteristics of this smaller figure are very similar to those of Olmec sculptures of infants, although the face is elderly.[112] This secondary figure is wearing a type of long skirt or train that is almost identical to one worn by an Olmec-style dancing jaguar figure found at Tuxtla Chico in Chiapas, Mexico.[112] This train extends down into the middle section of the column, continuing halfway down the back of the bat's head.[113] The position of the shoulders and the face of the principal figure are not anatomically correct, leading the archaeologists to conclude that the "face" is actually a chest ornament and that the actual head of the main figure is missing.[113] Although the upper section of the column contains many Olmec elements, it also lacks some distinctive features that are found in true Olmec art, such as the feline expression that is often depicted.[114]

The sculpture predates 300 BC, based on the style of the hieroglyphic text, and is thought to be an Early Maya monument that was intended to represent an Early Maya ruler (at the base) who carried the underworld (i.e. the bat) and his ancestors (the main figure above carrying a smaller figure on its back).[114] The Maya sculptor used half-remembered Olmec stylistic elements upon the ancestor figure in a form of Maya-Olmec syncretism, producing a hybrid sculpture.[114] As such it represents the transition from one cultural phase to the next, at a point where the earlier Olmec inhabitants had not yet been forgotten and were viewed as powerful ancestors.[115]

Inventory of altars

Altar 1 is found at the base of Stela 1. It is rectangular in shape with carved molding on its side.[118]

Altar 2 is of unknown provenance, having been moved to outside the administrator's house on the San Isidro Piedra Parada plantation. It is 1.59 metres (63 in) long, about 0.9 metres (35 in) wide and about 0.5 metres (20 in) high. It represents an animal variously identified as a toad and a jaguar. The body of the animal was sculptured to form a hollow 85 centimetres (33 in) across and 26 centimetres (10 in) deep. The sculpture was broken into three pieces.[119]

Altar 3 is a roughly worked flat, circular altar about 1 metre (39 in) across and 0.3 metres (12 in) high. It was probably associated originally with a stela but its original location is unknown, it was moved near to the manager's house on the San Isidro Piedra Parada plantation.[120]

Altar 5 is a damaged plain circular altar associated with Stela 2.[118]

Altar 7 is near the southern edge of the plaza on Terrace 3, where it is one of five monuments in a line running east–west.[77]

Altar 8 is a plain monument associated with Stela 5, positioned on the west side of Structure 12.[121]

Altar 9 is a low four-legged throne placed in front of Structure 11.[122]

Altar 10 was associated with Stela 13 and was found on top of the large offering of ceramics associated with that stela and the royal tomb in Structure 7A. The monument was originally a throne with cylindrical supports that was reused as an altar in the Classic period.[123]

Altar 12 is carved in the early Maya style and archaeologists consider it to be an especially early example dating to the first part of the Late Preclassic.[37] Because of the carvings on the upper face of the altar, it is supposed that the monument was originally erected as a vertical stela in the Late Preclassic, and was reused as a horizontal altar in the Classic. At this time 16 hieroglyphs were carved around the outer rim of the altar. The carving on the upper face of the altar represents a standing human figure portrayed in profile, facing left. The figure is flanked by two vertical series of four glyphs. A smaller profile figure is depicted facing the first figure, separated from it by one of the series of glyphs. The central figure is depicted standing upon a horizontal band representing the earth, the band is flanked by two earth monsters. Above the figure is a celestial band with part of the head of a sacred bird visible in the centre. The 16 glyphs on the rim of the monument are formed by anthropomorphic figures mixed with other elements.[124]

Altar 13 is another early Maya monument dating to the Late Preclassic. Like Altar 12 it was probably originally erected as a vertical stela. At some point it was deliberately broken, with severe damage inflicted upon the main portion of the sculpture, obliterating the central and lower portions. At a later date it was reused as a horizontal altar. The remains of two figures can be seen flanking the damage lower portion of the monument and the large head of the sacred bird survives above the area of damage. The right hand figure is wearing an interwoven skirt and is probably female.[125]

Altar 18 was one of five monuments forming a north–south row at the base of Structure 8 on Terrace 3.[77]

Altar 28 is located near Structure 10 in the Central Group. It is a circular basalt altar just over 2 metres (79 in) in diameter and 0.5 metres (20 in) thick. On the front rim of the altar is a carving of a skull. On the upper surface are two relief carvings of human feet.[116]

Altar 30 is embedded in the fourth step of the access stairway to Terrace 3 in the Central Group. It has four low legs supporting it and is similar to Altar 9.[117]

Altar 48 is a very early example of the Early Maya style of sculpture, dating to the first part of the Late Preclassic,[37] between 400 and 200 BC.[126] Altar 48 is fashioned from andesite and measures 1.43 by 1.26 metres (4.7 by 4.1 ft) and is 0.53 metres (1.7 ft) thick.[126] It is located near the southern extreme of Terrace 3, where it is one of a row of 5 monuments running east–west.[77] It is carved on its upper face and upon all four sides. The upper surface bears the intricate design of a crocodile with its body in the form of a symbol representing a cave and containing the figure of a seated Maya wearing a loincloth.[127] The sides of the monument are carved with an early form of Maya hieroglyphs, the text appears to refer directly to the person depicted on the upper surface.[127] Altar 48 had been carefully covered by Stela 14.[127] The emergence of a Maya ruler from the body of the crocodile parallels the myth of the birth of the Maya maize god, who emerges from the shell of a turtle.[128] As such, Altar 48 may be one of the earliest depictions of Maya mythology used for political ends.[126]

Inventory of monuments

Monument 1 is a volcanic boulder with the bas-relief sculpture of a ballplayer, probably representing a local ruler. This figure is facing to the right, kneeling on one knee with both hands raised. The sculpture was found near the riverbank at a crossing point of the river Ixchayá, some 300 metres (980 ft) to the west of the Central Group. It measures about 1.5 metres (59 in) in height. Monument 1 dates to the Middle Preclassic and is distinctively Olmec in style.[129]

Monument 2 is a potbelly sculpture found 12 metres (39 ft) from the road running between the San Isidro and Buenos Aires plantations. It is about 1.4 metres (55 in) high and 0.75 metres (30 in) in diameter. The head is badly eroded and inclined slightly forwards, its arms are slightly bent with the hands doubled downwards and the fingers marked. Monument 2 dates to the Late Preclassic.[130]

Monument 3 also dates to the Late Preclassic. It was relocated in modern times to the coffee-drying area of the Santa Margarita plantation. It is not known where it was originally found. It is a potbelly figure with a large head; it wears a necklace or pendant that hangs to its chest. It is about 0.96 metres (38 in) high and 0.78 metres (31 in) wide at the shoulders. The monument is damaged and missing the lower part.[131]

Monument 4 appears to be a sculpture of a captive, leaning slightly forward and with the hands tied behind its back. It was found on the lands of the San Isidro plantation but it is not known exactly where. It was moved to the Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología in Guatemala City. This monument probably dates to the Late Preclassic. It is 0.87 metres (34 in) high and about 0.4 metres (16 in) wide.[132]

Monument 5 was moved to the administrator's house of the San Isidro Piedra Parada plantation; the place where it was originally found is unknown. It measures 1.53 metres (60 in) in height and is 0.53 metres (21 in) wide at the widest point. It is a sculpture of a captive with the arms bound with a strip of cloth that falls across the hips.[133]

Monument 6 is a zoomorph sculpture discovered during the construction of the road that passes the site. It was moved to the Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología in Guatemala City. The sculpture is just over 1 metre (39 in) in height and is 1.5 metres (59 in) wide. It is a boulder carved into the form of an animal head, probably that of a toad, and is likely to date to the Late Preclassic.[136]

Monument 7 is a damaged sculpture in the form of a giant head. It stands 0.58 metres (23 in) and was found in the first half of the 20th century on the site of the electricity generator of the Santa Margarita plantation and moved close to the administration office. The sculpture has a large, flat face with prominent eyebrows. Its style is very similar to that of a monument found at Kaminaljuyu in the highlands.[137]

Monument 8 is found on the west side of Structure 12. It is a zoomorphic sculpture of a monster with feline characteristics disgorging a small anthropomorphic figure from its mouth.[88]

Monument 9 is a local style sculpture representing an owl.[138]

Monument 10 is another monument that was moved from its original location; it was moved to the estate of the Santa Margarita plantation and the place where it was originally found is unknown. It is about 0.5 metres (20 in) high and 0.4 metres (16 in) wide. This is a damaged sculpture representing a kneeling captive with the arms tied.[133]

Monument 11 is located in the southwestern area of Terrace 3, to the east of Structure 8. It is a natural boulder carved with a vertical series of five hieroglyphs. Further left is a single hieroglyph and the glyphs for the number 11. This sculpture is considered to be in an especially early Maya style and dates to the first part of the Late Preclassic.[140] It is one of a row of 5 monuments running east–west along the southern edge of Terrace 3.[77]

Monument 14 is an eroded Olmec-style sculpture dating to the Middle Preclassic. It represents a squatting human figure, possibly female, wearing a headdress and earspools. Under one arm it grips a jaguar cub, under the other it carries a fawn.[141]

Monument 15 is a large boulder with an Olmec-style relief sculpture of the head, shoulders and arms of an anthropomorphic figure emerging from a shallow niche, the arms bent inwards at the elbow. The back of the boulder is carved with the hindquarters of a feline, probably a jaguar.[142]

Monument 16 and Monument 17 are two parts of the same broken sculpture. This sculpture is classically Olmec in style and is heavily eroded but represents a human head wearing a headdress in the form of a secondary face wearing a helmet.[143]

Monument 23 dates to the Middle Preclassic period. It appears that it was an Olmec-style colossal head that was recarved into a niche figure sculpture.[144] If this was originally a colossal head then it would be the only example known from outside the Olmec heartland.[145] Monument 23 is sculpted from andesite and falls in the middle of the size range for confirmed Olmec colossal heads. It stands 1.84 metres (6.0 ft) high and measures 1.2 metres (3.9 ft) wide by 1.56 metres (5.1 ft) deep. Like the examples from the Olmec heartland, the monument features a flat back.[146] Lee Parsons contested John Graham's identification of Monument 23 as a recarved colossal head;[147] he viewed the side ornaments that Graham identified as ears as instead being the scrolled eyes of an open-jawed monster gazing upwards.[148] Countering this, James Porter has claimed that the recarving of the face of a colossal head into a niche figure is clearly evident.[149] Monument 23 was damaged in the mid-20th century by a local mason who attempted to break its exposed upper portion using a steel chisel. As a result, the top is fragmented, although the broken pieces were recovered by archaeologists and have been put back into place.[146]

Monument 25 is a heavily eroded relief sculpture of a figure seated in a niche.[150]

Monument 27 is located near the southern edge of Terrace 3, just south of a row of 5 sculptures running east–west.[77]

Monument 28 is situated near Monument 27 at the southern edge of Terrace 3.[77]

Monument 30 is located on Terrace 3, in a row of 5 monuments at the base Structure 8.[77]

Monument 35 is a plain monument on Terrace 6, it dates to the Late Preclassic.[91]

Monument 40 is a potbelly monument dating to the Late Preclassic.[151]

Monument 44 is a sculpture of a captive.[150]

Monument 47 is a local style monument representing a frog or toad.[138]

Monument 55 is an Olmec-style sculpture of a human head. It was moved to the Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología (National Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology).[150]

Monument 64 is an Olmec-style bas-relief carved onto the south side of a natural andesite rock and stylistically dates to the Middle Preclassic, although it was found in a Late Preclassic archaeological context. It was found in-situ on the eastern bank of the El Chorro stream, some 300 metres (980 ft) to the west of the South-Central Group. It represents an anthropomorphic figure with some feline characteristics. The figure is portrayed in profile and is wearing a belt. It holds a zigzag staff in its extended left hand.[152]

Monument 65 is a badly damaged depiction of a human head in Olmec style, dating to the Middle Preclassic. Its eyes are closed and the mouth and nose are completely destroyed. It is wearing a helmet. It is located to the west of Structure 12.[153]

Monument 66 is a local style sculpture of a crocodilian head that may date to the Middle Preclassic. It is located to the west of Structure 12.[155]

Monument 67 is a badly eroded Olmec-style sculpture showing a figure emerging from the mouth of a jaguar, with one hand raised and gripping a staff. Traces of a helmet are visible. It is located to the west of Structure 12 and dates to the Middle Preclassic.[156]

Monument 68 is a local style sculpture of a toad located on the west side of Structure 12. It is believed to date to the Middle Preclassic.[157]

Monument 69 is a potbelly monument dating to the Late Preclassic.[107]

Monument 70 is a local style sculpture of a frog or toad.[138]

Monument 93 is a rough Olmec-style sculpture dating from the Middle Preclassic. It represents a seated anthropomorphic jaguar with a human head.[141]

Monument 99 is a colossal head in potbelly style, dating to the Late Preclassic.[158]

Monument 100, Monument 107 and Monument 109 are small potbelly monuments dating to the Late Preclassic. They are all near the access stairway to Terrace 3 in the Central Group.[159]

Monument 108 is an altar placed in front of the main stairway giving access to Terrace 3, in the Central Group.[117]

Monument 113 is located outside of the site core, some 0.5 kilometres (0.31 mi) south of the Central Group, about 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) west of El Asintal, in a secondary site known as the South Group, which consists of six structure mounds. It is carved from an andesite boulder and bears a relief carving of a jaguar lying on its left side. Its eyes and mouth are open and various jaguar pawprints are carved upon the body of the animal.[69][72]

Monument 126 is a large basalt rock bearing bas-relief carvings of life-size human hands. It is found upon the bank of a small stream near the Central Group.[116]

Monument 140 is a Late Preclassic sculpture of a toad, it is located in the West Group, on Terrace 6.[91]

Monument 141 is a rectangular altar dating to the Late Preclassic. It is located in the West Group on Terrace 6.[91]

Monuments 142, 143, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149 and 156 are among 19 natural stone monuments that line the course of the Nima stream, some 200 metres (660 ft) west of the West Group, within the Buenos Aires and San Isidro plantations. They are basalt and andesite boulders that have deep circular depressions with polished sides that are perhaps the result of some kind of working activity.[160]

Monument 154 is a large basalt rock, it bears two petroglyphs representing childlike faces. It is located on the west side of the Nima stream, on the Buenos Aires plantation.[162]

Monument 157 is a large andesite rock on the west side of the Nima stream, on the San Isidro plantation. It bears the petroglyph of a face with eyes and eyebrows, nose and mouth.[162]

Monument 161 lies within the North Group, on the San Elías plantation. It is a basalt outcrop measuring 1.18 metres (46 in) high by 1.14 metres (45 in) wide on the side of the Ixchayá ravine. It bears a petroglyph of a face carved onto the upper part of the rock, looking upwards. The face has cheekbones, a prominent chin and a slightly open mouth. It has some stylistic similarity to Early Classic jade masks, although it lacks certain features associated with these.[163]

Monument 163 dates from the Late Preclassic. It was found reused in the construction of a Late Classic water channel beside Structure 7. It represents a seated figure with prominent male genitals and is badly damaged, with the head and shoulders missing.[164]

Monument 215 is a part of the Cargador del Ancestro sculpture.[81] It was found embedded in the east face of Structure 7A, where it was carefully placed at the same time as the royal burial was interred in the centre of the structure.[38]

Monument 217 is another part of the Cargador del Ancestro sculpture.[81] It was embedded in the east face of Structure 7A in the same manner, and at the same time, as Monument 215.[38]

Inventory of stelae

Stelae are carved stone shafts, often sculpted with figures and hieroglyphs. A selection of the most notable stelae at Takalik Abaj follows:

Stela 1 was found near to Stela 2 and moved near to the administrator's house of the San Isidro Piedra Parada plantation. It is 1.36 metres (54 in) high, 0.72 metres (28 in) wide and 0.45 metres (18 in) thick. It bears the sculpture of a standing figure facing to the left, holding a sceptre in the form of a serpent with a dragon mask at the lower end; a feline is on top of the serpent's body. It is similar in style to Stela 1 at El Baúl. A badly eroded hieroglyphic text is to the left of the figure's face, which is now completely illegible. This stela is early Maya in style, dating to the Late Preclassic.[165]

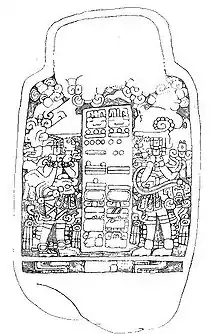

Stela 2 is a monument in the early Maya style that is inscribed with a damaged Long Count date. Due to its only partial preservation, this date has at least three possible readings, the latest of which would place it in the 1st century BC. Flanking the text are two standing figures facing each other, the sculpture probably represents one ruler receiving power from his predecessor. Above the figures and the text is an ornate figure depicted in profile looking down at the left-hand figure below.[167] Stela 2 is located in front of the retaining wall of Terrace 5.[94]

Stela 3 is badly damaged, being broken into three pieces. It was found somewhere on the San Isidro Piedra Parada plantation although its exact original location is not known. It was moved to a museum in Guatemala City. The lower portion of the stela depicts two legs facing to the left standing upon a horizontal band divided into three sections, each section containing a symbol or glyph.[168]

Stela 4 was uncovered in 1969 and moved near to the administrator's house on the San Isidro Piedra Parada plantation. It is of a style very similar to the stelae at Izapa and stands 1.37 metres (54 in) high.[169] The stela bears a complex design representing an undulating vision serpent rising toward the sky from the water flowing from two earth monsters, the jaws of the serpent are open wide towards the sky and from them emerges a characteristically Maya face. Several glyphs appear among the imagery. This stela is early Maya in style and dates to the Late Preclassic.[170]

Stela 5 is reasonably well preserved and is inscribed with two Long Count dates flanked by representations of two standing figures portraying rulers. The latest of these two dates is AD 126. The right-hand figure is holding a snake, while the left-hand figure is holding what is probably a jaguar.[171] This monument probably represents one ruler passing power to the next. A small seated figure is carved onto each of the sides of this stela along with a badly eroded hieroglyphic inscription. The style is early Maya and has affinities with sculptures at Izapa.[172]

Stela 12 is located near Structure 11. It is badly damaged, having been broken into fragments, of which two remain. The largest fragment is from the lower portion of the stela and depicts the legs and feet of a figure, both facing in the same direction. They stand upon a panel divided into geometric sections, each containing a further design. In front of the legs are the remains of a glyph that appears to be a number in the bar-and-dot format. A smaller fragment lies nearby.[88]

Stela 13 dates to the Late Preclassic. It is badly damaged, having been broken in two parts. It is carved in early Maya style and bears a design representing a stylised serpentine head, very similar to a monument found at Kaminaljuyu.[170] Stela 13 was erected at the base of the south side of Structure 7A. At the base of the stela was found a massive offering of more than 600 ceramic vessels, 33 prismatic obsidian blades, as well as other artifacts. The stela and the offering are associated with the Late Preclassic royal tomb known as Burial 1.[173]

Stela 14 is on the southern edge of Terrace 3, in the Central Group, where it is one of 5 monuments in an east–west row.[77] It is fashioned from andesite and has 26 cup-like depressions upon the upper surface.[126] It is one of the few such monuments found within the ceremonial centre of the city.[175] Altar 48 was found underneath Stela 14 in 2008, having been carefully covered by it in antiquity.[127] Stela 14 measures 2.25 by 1.4 metres (7.4 by 4.6 ft) by 0.75 metres (2.5 ft) thick and weighs more than 6 tonnes (6.6 short tons).[128] The lower surface of the stela had been sculpted completely flat with 6 small cupmarks and a series of marks forming a design reminiscent of the discarded skin of a snake or of a vertebral column.[126]

Stela 15 is another monument on the southern edge of Terrace 3, one of a row of five.[77]

Stela 29 is a smooth andesite monument at the southeast corner of Structure 11 with seven steps carved into its upper portion.[175]

Stela 34 was found at the base of Structure 8, where it was one of a row of five monuments.[77]

Stela 35 was another of the five monuments found at the base of Structure 8.[77]

Stela 53 is a fragment of sculpture that was found in the latter Early Preclassic phase of Structure 12, directly behind Stela 5.[38] Stela 53 forms a part of the Cargador del Ancestro sculpture.[38] Stela 5 was placed at the same time that Stela 53 was embedded in Structure 12, and the long count date on the former also allows the placing of Stela 53 to be fixed in time at Late Preclassic–Early Classic transition.[38]

Stela 61 is a part of the Cargador del Ancestro sculpture.[38] In the Late Preclassic–Early Classic transition it had been embedded in the east access stairway to Terrace 3.[38]

Stela 66 is a plain stela dating to the Late Preclassic. It is found in the West Group, on Terrace 6.[91]

Stela 68 was found at the southeast corner of Mound 61A on Terrace 5. This stela was broken in two and the remaining fragments appear to belong to two separate monuments. The stela, or stelae, once bore early Maya sculpture but this appears to have been deliberately destroyed, leaving only a few sculptured symbols.[176]

Stela 71 is an early Maya carved fragment reused in the construction of a water channel by Structure 7.[76]

Stela 74 is a fragment of Olmec-style sculpture that was found in the Middle Preclassic fill of Structure 7, where it was placed when that structure replaced the Pink Structure.[37] It bears a foliated maize design topped with a U-symbol within a cartouche and has other, smaller, U-symbols at its base.[37] It is very similar to a design found on Monument 25/26 from La Venta.[37]

Stela 87, discovered in 2018 and dating back to 100 BC, shows a king viewed from the side and holding a ceremonial bar with a maize deity emerging. To the right is a column of originally five cartouches holding what appear to be hieroglyphs, two of these showing elderly men, one of them bearded.[177]

Royal burials

A Late Preclassic tomb has been excavated, believed to be a royal burial. This tomb has been designated Burial 1; it was found during excavations of Structure 7A and was inserted into the centre of this Middle Preclassic structure.[178] The burial is also associated with Stela 13 and with a massive offering of more than 600 ceramic vessels and other artifacts found at the base of Structure 7A. These ceramics date the offering to the end of the Late Preclassic.[178] No human remains have been recovered but the find is assumed to be a burial due to the associated artifacts.[179] The body is believed to have been interred upon a litter measuring 1 by 2 metres (3.3 by 6.6 ft), which was probably made of wood and coated in red cinnabar dust.[179] Grave goods include an 18-piece jade necklace, two earspools coated in cinnabar, various mosaic mirrors made from iron pyrite, one consisting of more than 800 pieces, a jade mosaic mask, two prismatic obsidian blades, a finely carved greenstone fish, various beads that presumably formed jewellery such as bracelets and a selection of ceramics that date the tomb to AD 100–200.[180]

In October 2012, a tomb carbon-dated between 700 BC and 400 BC was reported to have been found in Takalik Abaj of a ruler nicknamed K'utz Chman ("Grandfather Vulture" in Mam) by archaeologists, a sacred king or "big chief" who "bridged the gap between the Olmec and Mayan cultures in Central America," according to Miguel Orrego. The tomb is suggested to be the oldest Maya royal burial to have been discovered so far.[181]

See also

- Balberta

- Bilbao (Mesoamerican site)

- K'iche' Kingdom of Q'umarkaj

- Ujuxte

Notes

- Popenoe de Hatch 2005, p. 997.

- García 1997, p. 176.

- Love 2007, p. 297. Popenoe de Hatch 2005, pp. 992, 994.

- Sharer and Traxler 2006, p. 236.

- Love 2007, p. 288.

- Sharer and Traxler 2006, p. 33.

- Adams 1996, p. 81.

- Popenoe de Hatch and Schieber de Lavarreda 2001, pp. 993–4.

- Wolley Schwarz 2001, pp. 1006, 1009.

- Christenson; Cassier and Ichon 1981, p. 26.

- Cassier and Ichon 1981, p. 26. Miles's first name is given variously as Suzanna (Kelly 1996, p. 215.), Susanna (Sharer and Traxler 2006, p. 239.) and Susan (Cassier and Ichon 1981, p. 26.)

- Cassier and Ichon 1981, p. 26.

- Van Akkeren 2005, pp. 1006, 1013.

- Cassier and Ichon 1981, p. 24.

- Zetina Aldana and Escobar 1994, p. 3. Kelly 1996, p. 210. Cassier and Ichon 1981, p. 24.

- Zetina Aldana and Escobar 1994, p. 3. Cassier and Ichon 1981, p. 24.

- Kelly 1996, p. 210.

- Zetina Aldana and Escobar 1994, p. 3.

- Popenoe de Hatch and Schieber de Lavarreda 2001, p. 991.

- Schieber de Lavarreda 1994, pp. 73–4.

- Zetina Aldana and Escobar 1994, p. 3. Rizzo de Robles 1991, p. 32.

- García 1997, p. 171.

- Zetina Aldana and Escobar 1994, p. 18.

- Rizzo de Robles 1991, p. 33.

- Popenoe de Hatch 2005, p. 996.

- Van Akkeren 2006, p.227.

- Sharer 2000, p. 455.

- Coe 1999, p. 64.

- Crasborn 2005, p. 696.

- Coe 1999, p. 30. Sharer and Traxler 2006, p. 37.

- Popenoe de Hatch 2005, pp. 992–3. Schieber de Lavarreda and Claudio Pérez 2005, p. 724.

- Crasborn 2005, p. 696. Popenoe de Hatch 2004, p. 415.

- Schieber de Lavarreda and Pérez 2004, pp. 405, 411.

- Popenoe de Hatch 2004, p. 424.

- Schieber Laverreda and Orrego Corzo 2010, p. 2.

- Schieber de Laverreda and Orrego Corzo 2010, p. 3.

- Sharer 2000, p. 468. Sharer & Traxler 2006, p. 248.

- Love 2007, pp. 291–2.

- Miller 2001, p. 59.

- Miller 2001, pp. 61–2.

- Adams 2000, p. 31.

- Love 2007, p. 293.

- Love 2007, p. 297.

- Love 2007, pp. 293, 297. Popenoe de Hatch and Schieber de Lavarreda 2001, p. 991.

- Orrego Corzo and Schieber de Lavarreda 2001, p. 788.

- Neff et al 1988, p. 345.

- Miller 2001, pp. 64–5.

- Kelly 1996, p. 210. Popenoe de Hatch and Schieber de Lavarreda 2001, p. 993.

- Popenoe de Hatch and Schieber de Lavarreda 2001, p. 993.

- Popenoe de Hatch 1987, p. 158.

- Popenoe de Hatch 1987, p. 154.

- Popenoe de Hatch 2005, p. 992.

- Kelly 1996, p. 212.

- Popenoe de Hatch and Schieber de Lavarreda 2001, p. 994

- Popenoe de Hatch and Schieber de Lavarreda 2001, p. 994. Popenoe de Hatch 2005, p. 993.

- Popenoe de Hatch 2005, pp. 992, 994.

- Popenoe de Hatch 2005, p. 993.

- Kelly 1996, p. 215.

- García 1997, p. 172.

- UNESCO.

- Love 2007, p. 293. Marroquín 2005, p. 958.

- Wolley Schwarz 2002, p. 365.

- Wolley Schwarz 2001, p. 1006.

- Tarpy 2004.

- Wolley Schwarz 2001, p. 1007.

- Schieber de Lavarreda and Pérez 2004, p. 410.

- Crasborn and Marroquín 2006, pp. 49–50.

- Wolley Schwarz 2001, pp. 1007, 1010. Schieber de Lavarreda and Pérez 2004, p. 410. Crasborn and Marroquín 2006, p. 49.

- Wolley Schwarz 2001, pp. 1006–7.

- Wolley Schwarz 2002, p. 371. Crasborn and Marroquín 2006, p. 49.

- Marroquín 2005, p. 955.

- Marroquín 2005, p. 956.

- Marroquín 2005, pp. 956–7.

- Marroquín 2005, pp. 957–8.

- Schieber de Lavarreda and Orrego Corzo 2009, p. 459.

- Wolley Schwarz 2001, pp. 1008–9. Schieber de Lavarreda and Pérez 2004, p. 410.

- Wolley Schwarz 2001, pp. 1010–11.

- Wolley Schwarz 2001, pp. 1007–8. Schieber de Lavarreda and Pérez 2004, p. 410.

- Schieber de Lavarreda and Orrego Corzo 2010, p. 1.

- Schieber de Lavarreda and Orrego Corzo 2011, p. 1.

- Schieber de Lavarreda 2003, p. 784. Schieber de Lavarreda 2002, p. 399.

- Schieber de Lavarreda and Orrego Corzo 2010, pp. 2–3.

- Popenoe de Hatch 2002, pp. 378–80.

- Schieber de Lavarreda and Pérez 2005, pp. 724–5. Popenoe de Hatch 2005, p. 997.

- Schieber de Lavarreda 2003, pp. 784, 787-8.

- Kelly 1996, p. 214.

- Crasborn 2005, pp. 695, 698.

- Schieber de Lavarreda and Orrego Corzo 2011, p. 5.

- Wolley Schwarz 2001, p. 1010.

- Jacobo 1999, p. 550. Schieber de Lavarreda and Pérez 2004, p. 410.

- Wolley Schwarz 2001, pp. 1008–9. Crasborn 2005, p. 698.

- Wolley Schwarz 2001, p. 1008.

- Schieber de Lavarreda and Orrego Corzo 2011, p. 6.

- Wolley Schwarz 2002, p. 365. Benson 1996, p. 23. Schieber de Lavarreda and Pérez 2006, p. 29.

- Benson 1996, p. 23. Orrego Corzo and Schieber de Lavarreda 2001, p. 786. Schieber de Lavarreda and Pérez 2006, p. 29.

- Orrego Corzo and Schieber de Lavarreda 2001, p. 786.

- Sharer 2000, pp. 476–7. Cassier and Ichon 1981, p. 30.

- Graham 1989, p. 232.

- Adams 1996, pp. 73, 81.

- Graham 1989, p. 235.

- Diehl 2004, p. 147. Graham has said that Takalik Abaj is the "most important Olmec site" known within Pacific Guatemala. (Graham 1989, p. 231.)

- Sharer 2000, p. 468. Orrego Corzo and Schieber de Lavarreda 2001, p. 788.

- Orrego Corzo and Schieber de Lavarreda 2001, pp. 791–2. Sharer 2000, pp. 476–7.

- Orrego Corzo and Schieber de Lavarreda 2001, pp. 791–2.

- Orrego Corzo and Schieber de Lavarreda 2001, pp. 786, 792.

- Schieber Lavarreda and Orrego Corzo 2010, p. 15.

- Schieber de Lavarreda and Orrego Corzo 2010, pp. 1, 3. Persson 2008.

- Schieber Lavarreda and Orrego Corzo 2010, pp. 1, 4.

- Schieber de Lavarreda and Orrego Corzo 2010, p. 4.

- Schieber de Lavarreda and Orrego Corzo 2010, pp. 4, 15.

- Schieber de Lavarreda and Orrego Corzo 2010, p. 5.

- Schieber de Lavarreda and Orrego Corzo 2010, pp. 5–6.

- Wolley Schwarz 2002, p. 368.

- García 1997, pp. 173, 187.

- Chang Lam 1991, p. 19.

- Cassier and Ichon 1981, pp. 33, 44.

- Cassier and Ichon 1981, p. 37.

- Kelly 1996, pp. 212–3.

- García 1997, p. 173.

- Schieber de Lavarreda 2002, pp. 399–402. Schieber de Lavarreda 2003, p. 791.

- Orrego Corzo and Schieber de Lavarreda 2001, pp. 789–90, 800.

- Orrego Corzo and Schieber de Lavarreda 2001, pp. 790, 802.

- Schieber de Lavarreda and Orrego Corzo 2009, p. 457.