Taplow Barrow

The Taplow Barrow is an early medieval burial mound in Taplow Court, an estate in the south-eastern English county of Buckinghamshire. Constructed in the seventh century, when the region was part of an Anglo-Saxon kingdom, it contained the remains of a deceased individual and their grave goods, now mostly in the British Museum. It is often referred to in archaeology as the Taplow burial.

.jpg.webp) | |

Shown within Buckinghamshire | |

| Location | Taplow Court |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 51.5311°N 0.6951°W |

| Type | Tumulus |

| History | |

| Periods | Early Medieval |

The Taplow burial was made in what archaeologists call the "conversion period", during which the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms were undergoing Christianisation. This period saw the erection of "Final Phase" burials: a select number of inhumations featuring lavish grave goods far richer than the graves of the preceding "migration period" (fifth and sixth centuries). The majority of these Final Phase burials were spatially separate from the new churchyard burials, although the Taplow Burial—which was likely placed next to an early church—is one of the few known exceptions. Located atop a hill, the area around it was previously an Iron Age hillfort and offers widespread views of the local landscape.

Interred beneath the mound was a single individual—interpreted by archaeologists as a local chieftain—buried with a range of grave goods. These included military gear such as a sword, three spears, and two shields, as well as other items like drinking horns and glass beakers. Such elite items likely reflected the individual's aristocratic status. Several of these items were of probable Kentish manufacture, suggesting that the individual may have had links with the Kingdom of Kent. Little of the body survived, preventing osteoarchaeological analysis to determine their age or sex, although the content of the grave goods has led archaeologists to believe the individual was male.

The mound was excavated in 1883 by three local antiquarians. At the time, it represented the most lavish Anglo-Saxon burial then known and remained so until the discovery of the ship burial at Sutton Hoo, Suffolk in the 1930s. At the request of the clergyman in charge of the churchyard, the grave goods recovered were donated to the British Museum, where many of them remain on display.

Context

In early medieval English archaeology, the seventh-century is sometimes termed the "conversion period" to distinguish it from the preceding "migration period".[1]

A broad range of funerary monuments were erected in early medieval England, among the best known of which are earthen tumuli often known as "barrows".[2] Many early medieval barrows have been destroyed, although a few survive, albeit in a much denuded form: these include the sixth-century barrows at Greenwich Park, London, the early seventh-century barrows at Sutton Hoo, Suffolk, and the late-ninth century barrows at Heath Wood, Derbyshire.[2] As well as these larger surviving barrows, smaller barrows were possibly also found in early medieval cemeteries in south-eastern England. Excavation has found penannular and annular ring-ditches around various inhumation burials at cemeteries like Finglesham, Polhill, and Eastern, which archaeologists have interpreted as the quarry ditches and perimeters of since lost burial mounds.[2]

— The historian John Blair[3]

The archaeologist Martin Carver argued that the burial mounds erected in the late sixth and seventh centuries were created by practitioners of Anglo-Saxon paganism defiantly displaying their beliefs and identity in the face of encroaching Christianity.[4] In his view, these lavish barrow burials were "selected from a demonstrably pagan repertoire".[5] The historian John Blair disagreed, suggesting that "they are not relics of entrenched pagan practice, even if one purpose of them was to manufacture links with an imagined past suggested by prehistoric barrows."[3] Blair attributed them to a growing "striving for a monumental expression of status", which in more solidly Christian societies of the time was also finding form through funerary churches and above-ground sarcophagi.[3]

In early medieval England—unlike in neighbouring Francia—grave goods are very rare in churchyard burials.[6] The archaeologist Helen Geake observed that typically, "Final Phase" style burials and "churchyard-type" burials were mutually exclusive in seventh-century England, even if they were located within a few miles of each other.[7] Taplow is one of a few exceptions to this, representing a lavishly furnished "Final Phase" style burial inside a churchyard. Other examples of grave-goods being used in churchyards of this period are known from Eccles, Kent, St Paul-in-the-Bail, Lincoln, and from records of the grave of St Cuthbert.[8]

History

The name Taplow itself is in origin that of the burial mound, from Old English Tæppas hláw "Tæppa's mound", so that the name of the unknown chief or nobleman buried in the mound would seem to have been Tæppa. Stevens suggested that it derived from hlæw (mound) and tap or top, meaning "the mound on the crest of the hill".[9]

During Stevens' investigation, the mound measured 15 feet in eight at its centre, and 240 feet in circumference.[10] He described it as being "somewhat bell-shaped", suggesting that this had been caused by the addition of later inhumation burials around its eastern perimeter.[11]

The Taplow barrow is located within an earlier Iron Age hillfort.[12] It is positioned on the only hill in the area which offers long-distance views in most directions, which was likely a deliberate decision by its builders.[12] The archaeologist Howard Williams suggested that this prominent landscape location was chosen "to assert claims over land and territory, and express a new identity for the deceased and his kin". In this way, Williams argued, the mound was more than just "a 'marker' for the dead, but something that evoked status, and aspired pasts and futures, and perhaps also the presence of the dead active within the mound."[12] A similar choice of location, overlooking the landscape, was chosen for the roughly contemporary barrow at Asthall, Oxfordshire, which contained an early seventh-century cremation burial.[12]

Without a fuller excavation of the churchyard having been carried out, the relationship of the mound to other early medieval burials and to the church itself is unclear.[13] Leslie Webster noted that the connection between the church and the mound "raises fundamental questions about the mechanisms of conversion and the assertion of secular power in the conversion period."[14]

The deceased individual

Various archaeologists have suggested that the interned individual was male.[15] After completing his excavation of the site, Stevens concluded that the individual interned was "a great chief" who ruled before Christianity came to Anglo-Saxon England. Given that Buckinghamshire was in Mercia for much of this period, Stevens noted that "it is not beyond the bounds of probability that he was a Mercian Angle of distinction."[16]

The archaeologists Stuart Brookes and Sue Harrington noted that the individual buried at Taplow has often been considered to be "a Kentish 'prince' by virtue of the sheer quality and point of origin of his material culture".[17] They added that the burial had "prompted discussion on the strategic importance of Kentish hegemony over the productive Upper Thames Valley" during the seventh century.[17] Webster suggested that the deceased was "a local ruler who controlled a key section of the Thames valley on behalf of Kentish overlords", the latter indicated by the "significant number" of Kentish artefacts in the grave.[14]

Grave goods

The 1883 excavation found that the soil of the mound contained various worked flint tools, including scrapers, cores, and flints, worked animal bones, and pieces of Romano-British pottery, including a sherd of Samian ware. This material was unlikely to be deliberately placed there but was interpreted as having been mixed up in the soil that the mound's early medieval builders used.[18]

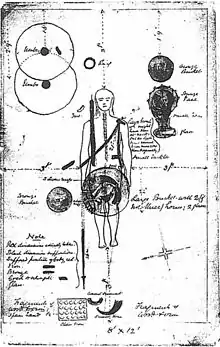

The burial was located beneath the base of the mound itself.[18] The grave was determined to measure twelve feet by eight feet and was aligned on an east to west axis.[19] On its base was a layer of fine gravel.[19] The only remaining physical evidence of the body was a thigh bone and fragments of vertebral bones; there was no evidence of any teeth, which typically survive best.[20] Shreds of fabric were found, which excavators examined under a microscope and thought were woollen.[21]

The grave goods at Taplow were "not as rich or as eclectic" as those in Sutton Hoo Mound I, leading Leslie Webster to suggest that it was "of somewhat lesser status".[14] The historian John Blair nevertheless compared Taplow with Sutton Hoo, stating that these were "remarkable for the extraordinary range and richness of their grave-goods, and must commemorate people of more than simply local status."[3]

Artefacts

Among the grave goods, now in the British Museum, were 19 vessels for feasting and drinking, at least three weapon sets, a lyre, a gaming board, and rich textiles, the whole ensemble "recognisably a version of the standard Germanic princely kit". Many of the objects seem to be of Kentish origin. The several gold braids in the burial may have been a symbol of royalty, and the largest horns and the belt buckle were apparently already old when buried, suggesting the treasure of a "Kentish princely family".[22]

The exact location of these items in the grave was not determined with any accuracy, with excavators attributing this to the collapse of the mound into the burial chamber.[19] Stevens nevertheless offered suggestions as to where the items had been placed based on what he and others observed during the excavation.[23] Evidence for rotten wood was found, leading to the suggestion that a wooden plank had been placed atop the body.[23]

- An iron sword measuring 30 inches in length and 2 1/2 inches wide. The excavators believed that traces of the scabbard could be seen in the grave.[24] This was found to the left hand side of the body.[23]

- Two iron shield bosses, each 5 inches wide and 3 1/2 inches in height.[24] These were located near the head of the grave, to the right of the body.[23]

- An iron link and iron ring.[24]

- Three iron spearheads. One was of the angon type and measured 26 inches in length. The other two were smaller.[24] These were on the right hand side of the body.[23]

- An iron knife or small seax.[24]

- An iron cauldron or tub lined with bronze, that was two foot in diameter. It had been crushed.[24] This was located crushed alongside one of the two buckets against the thighs.[23]

- Two buckets made from timber staves with bronze fittings.[24] One was crushed alongside the cauldron at the thighs; the other was found on the left-hand side of the body, near to the head.[23]

- A twelve-sided bronze bowl with two handles. This had also been crushed.[24] This was on the left hand side of the body.[23]

- Four green glass drinking cups. These had been broken.[25] Three of these were found inside the tub; the fourth was at the foot of the grave.[23]

- Two large drinking horns with gilded silver mounts around their rims. The mounts had been crushed.[19] These were found inside the tub.[23]

- Four smaller horns or cups with mounts; these were found in a fragmentary state.[19] One was on the left hand side of the body, and the other at the foot of the burial.[23]

- Shreds of gold, found spread over an area of about two yards and believed to have been from some fabric.[19]

- A gold buckle decorated with garnets, measuring 4 inches in length.[19] The excavators thought that this had been placed about three feet east of the femur.[23]

- Two pairs of metal clasps, possibly gold, which were suggested as having been attached to a girdle.[19] These were believed to have been placed toward the left hand side of the body.[23]

- A crescent-shaped metal ornament about 6 inches in length.[19] This was found at the foot of the grave.[23]

- Several bone draughtsmen.[19] These were found at the foot of the grave.[23]

All at the British Museum, with several displayed in Room 41:

- Pair of drinking horns

- Gold belt buckle (illustrated above)

- Four glass claw beakers

- Set of gaming pieces

Williams suggested that the choice of grave goods placed within the mound alluded to "an aristocratic lifestyle in this world and the next".[12] Taplow remained what archaeologist Leslie Webster called "the most prestigiously furnished Anglo-Saxon burial" known until the discovery of the ship burial beneath Sutton Hoo Mound 1.[26] In 2010, Brookes and Harrington stated that the Taplow burial remained "second only to Sutton Hoo in wealth and display".[17]

Church

The historian John Blair argued that the existence of a pre-Viking church "cannot be sustained from the parch-mark evidence".[27]

Taplow is not the only example where a church was built adjacent to an elite barrow burial, as other examples are known from High Wycombe in Buckinghamshire and Ogbourne St Andrew in Wiltshire.[28] Blair raised the point that these churches may have been established in the tenth or early eleventh centuries "to Christianize tombs to which folk-legends attached, and which were identified with ancestors or local worthies".[27]

Excavation

In October 1883, an excavation of the barrow was made by Mr Rutland, the Honorary Secretary of the Berkshire Archaeological and Architectural Society, with the assistance of Major Cooper King, Joseph Stevens, and Walter Money.[9] In total, it took around three weeks.[24] Stevens noted that at the time of excavation, a felled yew tree—likely several centuries old—was located in the centre of the barrow.[10] To excavate, a horizontal shaft six feet in width was dug on the south of the mound and then expanded toward its centre. A similar process was then repeated on the north side and then the west side.[9] During the excavation, soil from beneath the yew tree collapsed into the trench, injuring Rutland; the investigation was paused for several days as a result.[18] On resuming the project, the excavators found the body beneath the mound, but shortly after the yew tree fell over into the trench, which delayed the project further. Only after the tree was removed could the grave goods be recovered.[29] He noted that following the investigation, the mound was "restored to its former dimensions".[10]

The grave goods were taken to Rutland's house, where they were temporarily exhibited.[24] The Reverend Charles Whately, the custodian of the churchyard, then offered them to the Trustees of the British Museum, who accepted.[24] Stevens noted that the grave goods reflected "a strongly marked Gothic element" and thus suggested that the interned individual might have been a Viking, although concluded that an Anglo-Saxon origin was more likely.[30]

References

Footnotes

- Geake 2002, p. 144.

- Williams 2006, p. 147.

- Blair 2005, p. 53.

- Carver 1998, pp. 16–20.

- Carver 1998, p. 20.

- Geake 2002, p. 149.

- Geake 2002, p. 151.

- Geake 2002, pp. 150–151.

- Stevens 1884, p. 62.

- Stevens 1884, p. 61.

- Stevens 1884, pp. 61–62.

- Williams 2006, p. 202.

- Geake 2002, p. 150.

- Webster 1999, p. 440.

- Brookes & Harrington 2010, p. 76.

- Stevens 1884, p. 70.

- Brookes & Harrington 2010, p. 78.

- Stevens 1884, p. 63.

- Stevens 1884, p. 65.

- Stevens 1884, pp. 65–66.

- Stevens 1884, p. 67.

- Tyler, 55-56; 56 quoted

- Stevens 1884, p. 66.

- Stevens 1884, p. 64.

- Stevens 1884, pp. 64–65.

- Webster 1999, pp. 439–440.

- Blair 2005, p. 377.

- Blair 2005, p. 367.

- Stevens 1884, pp. 63–64.

- Stevens 1884, pp. 67–68.

Bibliography

- Blair, John (2005). The Church in Anglo-Saxon Society. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198226956.

- Brookes, Stuart; Harrington, Sue (2010). The Kingdom and People of Kent AD 400–1066: Their History and Archaeology. Stroud: The History Press.

- Carver, Martin (1998). "Conversion and Politics on the Eastern Seaboard of Britain; Some Archaeological Indicators". In Barbara E. Crawford (ed.). Conversion and Christianity in the North Sea World. University of St Andrews.

- Geake, Helen (2002). "Persistent Problems in the Study of Conversion-Period Burials in England". In Sam Lucy; Andrew Reynolds (eds.). Burial in Early Medieval England and Wales. London: Society for Medieval Archaeology. pp. 144–155.

- Stevens, Joseph (1884). "On the Remains found in an Anglo-Saxon Tumulus at Taplow, Bucks". Journal of the British Archaeological Association. 40: 61–71. doi:10.1080/00681288.1884.11887687.

- Stocker, David; Went, D. (1995). "The Evidence of a Pre-Viking Church Adjacent to the Anglo-Saxon Barrow at Taplow, Buckinghamshire". Archaeological Journal. 152: 441–454. doi:10.1080/00665983.1995.11021436.

- Webster, Leslie (1992). "Death's Diplomacy: Sutton Hoo in the Light of Other Male Princely Burials". In R. Farrell; C. Newman de Vegvar (eds.). Sutton Hoo: Fifty Years After. Oxford: Oxbow. pp. 75–82.

- Webster, Leslie (1999). "Taplow Burial". In Michael Lapidge (ed.). The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford and Malden: Blackwell. pp. 439–440.

- Williams, Howard (1998). "Monuments and the Past in Early Anglo-Saxon England". World Archaeology. 30 (1): 90–108. doi:10.1080/00438243.1998.9980399. JSTOR 125011.

- Williams, Howard (1999). "Placing the Dead: Investigating the Location of Wealthy Barrow Burials in Seventh-Century England". In M. Rundkvist (ed.). Grave Matters: Eight Studies of Burial Data from the First Millennium AD from Crimea, Scandinavia and England. BAR International Series 781. Oxford. pp. 57–86.

- Williams, Howard (2006). Death and Memory in Early Medieval Britain. Cambridge Studies in Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

- Leslie Webster, The Rise, Resuscitation of the Taplow Burial (2001).

- Audrey Meaney, A Gazetteer of Early Anglo-Saxon Burial Sites (1964).

- Michael Lapidge, John Blair, Simon Keynes (eds.), The Blackwell encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England, Wiley-Blackwell (2001), ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

- Tyler, Elizabeth M.,Treasure in the medieval West, 2000, Boydell & Brewer Ltd, ISBN 0-9529734-8-0, ISBN 978-0-9529734-8-5, google books

External links

- Taplow Burial at The Megalithic Portal

- Taplow Burial at Buckinghamshire County Council

- Saxon barrow, church and cemeteries in the old churchyard at Taplow Court at Historic England

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tappa's Tump. |