Tati River

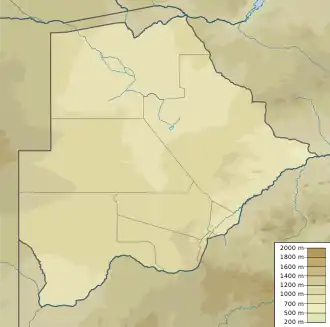

The Tati River is a river in northeast Botswana, a tributary of the Shashe River, which in turn is a tributary of the Limpopo River. The river flows through Francistown, where it is joined by the Ntshe (or Inchwe) River from the left.[1]

| Tati River | |

|---|---|

| Location | |

| Country | Botswana |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • coordinates | 20.506782°S 27.679869°E |

| Mouth | |

• location | Shashe River |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Inchwe River |

History

About 1865 a hunter came across traces of old gold diggings near the Tati.[2] He invited Karl Mauch to accompany him on his next trip, and in 1866 Mauch announced that he had found the Tati goldfields extending about 80 by 3 miles (128.7 by 4.8 km)[3] which started the first gold rush in Southern Africa the following year.[4] In 1869 the Englishman Daniel Francis came to hunt for gold on the river, before heading south to the Kimberley diamond fields in 1870.[5] The gold was hard to extract, and the gold rush died down.[6] Francis returned in 1880 and obtained mining rights from King Lobengula.[7][5] Mining activity revived in the 1880s and 1890s, and Francistown was established in 1897 when the railway arrived. The town was named after Francis, who owned most of the land in the area.[6]

Use

The sandy bed of the Tati river holds water only for a few days in each year, as is common with rivers in Botswana.[8] The river feeds the Ntimbale Dam, with a storage capacity of 26,370,000 cubic metres (931,000,000 cu ft).[9] The dam, commissioned in 2008, supplies water to villages throughout the North East District.[10] Lower down the river supplies the Dikgatlhong Dam.[1]

The water has become polluted from industrial and human waste, and there is a risk of cholera if the water is used untreated. During the extended dry season, the river loses its surface water, although water may remain in the sand bed. Mining of this sand has caused the water table to drop, and may also contribute to flooding.[1]

References

Citations

- Bule 2010.

- White 2004, p. 2.

- White 2004, p. 3.

- Eriksson, Altermann & Förtsch 1995, p. 85.

- Murphy et al. 2010, p. 85.

- Main 2001, p. 96.

- Jenny (2014-08-12). "The Rudd concession". 1870 to 1918. Retrieved 2017-02-15.

- Nas 1993, p. 192.

- Central Statistics Office 2009, p. 6.

- Kologwe 2008.

Sources

- Bule, Edward (11 June 2010). "Tati River: A jewel or environmental trap?". Mmegi Online. Retrieved 2012-09-19.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Central Statistics Office (October 2009). "BOTSWANA WATER STATISTICS" (PDF). Archived from the original on July 7, 2010. Retrieved 2012-09-18.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- Eriksson, Patrick G.; Altermann, W.; Förtsch, E. B. (1995). "Transvaal Sequence and Bushveld Complex". Mineralium Deposita. 30 (2): 85–88. doi:10.1007/BF00189337.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kologwe, Obusitse (2008-10-26). "Ntimbale Dam to benefit North East region at last". Sunday Standard. Retrieved 2012-09-19.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Main, Michael (2001-10-31). African Adventurer's Guide to Botswana. Struik. ISBN 978-1-86872-576-2. Retrieved 2012-09-19.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Murphy, Alan; Armstrong, Kate; Bainbridge, James; Firestone, Matthew D. (2010-03-11). Southern Africa. Lonely Planet. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-74059-545-2. Retrieved 2012-09-19.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nas, P. (1993). Urban Symbolism. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-09855-8. Retrieved 2012-09-19.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- White, John (2004-03-04). Scientific Travellers, 1789-1874. Taylor & Francis. Retrieved 2012-09-19.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)