Taxi dancer

A taxi dancer is a paid dance partner in a partner dance. Taxi dancers are hired to dance with their customers on a dance-by-dance basis. When taxi dancing first appeared in taxi-dance halls during the early 20th century in the United States, male patrons would typically buy dance tickets for a small sum each.[1][2][3] When a patron presented a ticket to a chosen taxi dancer, she would dance with him for the length of a single song. The taxi dancers would earn a commission on every dance ticket earned. Though taxi dancing has for the most part disappeared in the United States, it is still practised in some other countries.

Etymology

The term "taxi dancer" comes from the fact that, as with a taxi-cab driver, the dancer's pay is proportional to the time he or she spends dancing with the customer. Patrons in a taxi-dance hall typically purchased dance tickets for ten cents each, which gave rise to the term "dime-a-dance girl". Other names for a taxi dancer are "dance hostess" and "taxi" (in Argentina). In the 1920s and 30s, the term "nickel hopper" gained popularity in the United States because out of each dime-a-dance, the taxi dancer typically earned five cents.[4]

History

Taxi dancing traces its origins to the Barbary Coast district of San Francisco which evolved from the California Gold Rush of 1849. In its heyday the Barbary Coast was an economically thriving place of mostly men that was frequented by gold prospectors and sailors from all over the world.[5] That district created a unique form of dance hall called the Barbary Coast dance hall, also known as the Forty-Nine['49] dance hall. Within a Barbary Coast dance hall female employees danced with male patrons, and earned their living from commissions paid for by the drinks they could encourage their male dance partners to buy.[6]

Still later after the San Francisco Earthquake of 1906 and during early days of jazz music, a new entertainment district developed in San Francisco and was nicknamed Terrific Street.[7][8][9] And within that district an innovative dance hall, The So Different Club, implemented a system where customers could buy a token which entitled them to one dance with a female employee.[10][11] Since dancing had become a popular pastime, many of The So Different Club's patrons would go there to see and learn the latest new dances.[12]

However in 1913 San Francisco enacted new laws that would forbid dancing in any cafe or saloon where alcohol was served.[13] The closure of the dance halls on Terrific Street fostered a new kind of pay-to-dance scheme, called a closed dance hall, which did not serve alcohol.[14] That name was derived from the fact that female customers were not allowed — the only women permitted in these halls were the dancing female employees.[15] The closed dance hall introduced the ticket-a-dance system which became the centerpiece of the taxi-dance hall business model.[14] A taxi dancer would earn her income by the number of tickets she could collect in exchange for dances.

Taxi dancing then spread to Chicago where dance academies, which were struggling to survive, began to adopt the ticket-a-dance system for their students.[16] The first instance of the ticket-a-dance system in Chicago occurred at Mader-Johnson Dance Studios. The dance studio's owner, Godfrey Johnson, describes his innovation:

I was in New York during the summer of 1919, and while there visited a new studio opened by Mr. W___ W___ of San Francisco, where he had introduced a ten-cent-ticket-a-dance plan. When I got home I kept thinking of that plan as a way to get my advanced students to come back more often and to have experience dancing with different instructors. So I decided to put a ten-cent-a-lesson system in the big hall on the third floor of my building... But I soon noticed that it wasn't my former pupils who were coming up to dance, but a rough hoodlum element from Clark Street... Things went from bad to worse; I did the best I could to keep the hoodlums in check.[17]

This system was so popular at dance academies that taxi-dancing system quickly spread to an increasing number of non-instructional dance halls.

Taxi dancers typically received half of the ticket price as wages and the other half paid for the orchestra, dance hall, and operating expenses.[18] Although they only worked a few hours a night, they frequently made two to three times the salary of a woman working in a factory or a store.[19] At that time, the taxi-dance hall surpassed the public ballroom in becoming the most popular place for urban dancing.[20]

Taxi-dance halls flourished in the United States during the 1920s and 1930s, as scores of taxi-dance halls opened in Chicago, New York, and other major cities. In 1931 there were over 100 taxi-dance halls in New York City alone, patronized by between 35,000 and 50,000 men every week.[21][22]

However, by the mid 1920s, in New York City and other towns and cities across the United States, taxi-dance halls were coming under increasing attack by reform movements who deemed some establishments dens of iniquity, populated mainly by charity girls or outright prostitutes. Reform in the form of licensing and police supervision was insisted on, and eventually some dance halls were closed for lewd behavior.[23] In San Francisco where it all started, the police commission ruled against the employment of women as taxi dancers in 1921, and taxi dancing in San Francisco would forever become illegal.[24]

After World War II the popularity of taxi dancing in the United States began to diminish. By the mid-1950s large numbers of taxi-dance halls had disappeared, and although a handful of establishments tried to hold on for a few more years in New York City and elsewhere, taxi dancing had all but vanished from the nightlife scene in the U.S. by the 1960s.[25]

Background of the taxi dancer

What is generally known today about the taxi dancer of the 1930s comes from a major sociological study published by The University of Chicago Press in 1932 (see Classic sociological study below). According to the study, the typical taxi dancer in the 1920s and 30s was an attractive young woman between the age 15 and 28 who was usually single. Although some dancers were undoubtedly older, the taxi-dancer profession skewed strongly toward the young and single. A majority of the young women came from homes in which there was little or no financial support from a father or father figure. The dancers were occasionally runaways from their families, and it was not unusual for a young woman to be from a home where the parents had separated. Despite their relatively young age range, a sizable percentage of taxi dancers had been previously married.

Many times the dancers were immigrants from European countries, such as Poland, Sweden, the Netherlands, Germany, and France. Due to cultural differences, conflicts often would arise between parents and their dancing offspring, especially if the parents were originally from rural areas. Sometimes a young woman of an immigrant family who worked as a taxi dancer was the primary financial support of the family. When this occurred and the young woman supplanted the parent or parents as breadwinner, sometimes she would assume an aggressive role in the family by "subordinating the parental standards to her own requirements and demands."

These conflicts in values between young women taxi dancers and their parents frequently caused the young women to lead so-called "double lives," denying that they worked at a taxi-dance hall. To further this divide, the young women would sometimes adopt aliases so that their activities might not reach their families' ears. When parents found out, there were three typical outcomes: the young woman either gave up her dancing career, or she left home and became estranged from the family, or the family accepted the young women's conduct, however reluctantly, due to financial necessity.

Despite the frequent hardships, the 1932 sociological study found that many taxi dancers seemed to enjoy the lifestyle and its enticements of "money, excitement, and affection." Most young women interviewed for the study spoke favorably about their experiences in the taxi-dance hall.

One dancer [case #15] from the 1920s describes her start at a taxi-dance hall:

I was working as a waitress in a Loop restaurant for about a month. I never worked in a dance hall like this and didn't know about them. One day the "boss" of this hall was eating in the restaurant and told me I could make twice as much money in his "dancing school." I went there one night to try it – and then quit my job at the restaurant. I always liked to dance anyway, so it was really fun.

And yet another dancer from Chicago [case #11] spoke very positively of her experiences:

After I had gotten started at the dance hall I enjoyed the life too much to want to give it up. It was easy work, gave me more money than I could earn any other way, and I had a chance to meet all kinds of people. I had no dull moments. I met bootleggers, rum-runners, hijackers, stick-up men, globe-trotters, and hobos. There were all different kinds of men, different from the kind I'd be meeting if I'd stayed at home with my folks in Rogers Park... After a girl starts in the dance hall and makes good it's easy to live for months without ever getting outside the influence of the dance hall. Take myself for instance: I lived with other dance-hall girls, met my fellows at the dance hall, got my living in the dance hall. In fact, there was nothing I wanted that I couldn't get through it. It was an easy life, and I just drifted along with the rest. I suppose if something hadn't come along to jerk me out, I'd still be a drifter out on the West Side.

Classic sociological study

In 1932, The Taxi-Dance Hall: A Sociological Study in Commercialized Recreation and City Life by researcher Paul G. Cressey was published by The University of Chicago Press. Examining the taxi-dancing milieu in Chicago, utilizing vivid, firsthand interviews of taxi dancers as well as their patrons, the book brought to light the little known world of the taxi dance hall. The study is now considered one of the classic urban ethnographies of the Chicago School.[26]

Vocabulary of the dancers

As taxi dancing evolved to become a staple in the American nightlife of the 1920s and 30s, taxi dancers developed an argot of their own. In his 1932 sociological study, Cressey took note of the specialized vocabulary in the Chicago dance halls:[27]

- black and tan – a colored and white cabaret

- buying the groceries – living in a clandestine relationship

- class – term used by Filipinos to denote the taxi-dance halls

- fish – a man whom the girls can easily exploit for personal gain

- fruit – an easy mark

- hot stuff – stolen goods

- line-up, the– immorality engaged in by several men and a girl

- make – to secure a date with

- mark – a person who is gullible and easily taken advantage of

- monkey-chaser – a man interested in a taxi dancer or chorus girl

- monkey shows – burlesque shows with chorus girls

- nickel-hopper – a taxi dancer

- on the ebony – a taxi-dance hall or taxi dancer having social contacts with men of races other than white

- opera – burlesque show

- paying the rent – living in a clandestine relationship

- picking up – securing an after-dance engagement with a taxi dancer

- playing – successfully exploiting one of the opposite sex

- professional – a government investigator; one visiting the taxi-dance hall for ulterior purposes

- punk – a novitiate; an uninitiated youth or young girl, usually referring to an unsophisticated taxi dancer

- racket – a special enterprise to earn money, honestly or otherwise

- shakedown – enforced exaction of graft

Taxi dancers today

Although the ticket-per-dance system of taxi dancing has become nearly nonexistent in the United States and around the world, some nightclubs and dance instruction establishments continue to offer dancers who may be hired as dance partners.[28] Most often these dance partners are female, but sometimes male. Instead of being called taxi dancers, the dancers are today usually referred to as "dance hostesses." Dance hostesses are often employed to assist beginners to learn to dance or may be utilized to further the general goal of building the dance community of an establishment.

In social settings and social forms of dance, a partner wanting constructive feedback from a dance hostess must explicitly request it. As the hostess's role is primarily social, she (or he) is unlikely to criticize directly. Due to the increased profile of partner dances during the 2000s, hostessing has become more common in settings where partners are in short supply, for either male or female dancers. For example, male dancers are often employed on cruise ships to dance with single female passengers. This system is usually referred to as the Dance Host program. Dance hostesses (male and female) are also available for hire in Vienna, Austria, where dozens of formal balls are held each year.

Volunteer dance hostesses (experienced male and female dancers) are often used in dance styles such as Ceroc to help beginners.

United States

There remain a handful of nightclubs in the United States, particularly in the cities of New York and Los Angeles, where an individual can pay to dance with a female dance hostess.[29] Usually these modern clubs forgo the use of the ticket-a-dance system, and instead have time-clocks and punch-cards that allow a patron to pay for the dancer's time by the hour. Some of these dance clubs operate in buildings where taxi dancing was done in the early 20th century. No longer called taxi-dance halls, these latter-day establishments are now called hostess clubs.[30]

Argentina

The growth of tango tourism in Buenos Aires, Argentina, has led to an increase in formal and informal dance hostess services in the milongas, or dance halls. While some operators attempt to sell holiday romance, reputable tango agencies offer genuine host services to tourists who find it hard to cope with the cabeceo—the eye contact and nodding-method of finding a dance partner.

Taxi dancers in popular culture

Since the 1920s when taxi dancing boomed in popularity, various films, songs and novels have been released reflecting the pastime, often using the taxi-dance hall as a setting or chronicling the lives of taxi dancers.

Movies

- Dance Hall (1929), pre-Code musical based on a Viña Delmar short story

- The Nickel-Hopper (1926), silent short

- Ten Cents a Dance (1931), starring Barbara Stanwyck; inspired by the popular song of the same name

- Let's Dance (1933), short featuring George Burns as a sailor and Gracie Allen as a dance hostess at Roseland Dance Hall

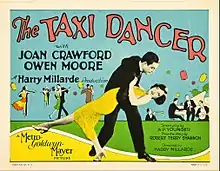

- The Taxi Dancer (1927), starring Joan Crawford and Owen Moore

- Asleep in the Feet (1933), Hal Roach comedy short starring Thelma Todd and ZaSu Pitts

- Dime-A-Dance (1937) featuring Al Christie and Imogene Coca

- Sweet Charity (1969), musical-comedy starring Shirley MacLaine; directed and choreographed by Bob Fosse

- Child of Manhattan (1937), based on a play by Preston Sturges

- Killer's Kiss (1955), a film by Stanley Kubrick, various scenes take place in a taxi-dance hall

- The Rat Race (1960), starring Debbie Reynolds as a struggling taxi dancer, based on a play by Garson Kanin

- A League of Their Own (1992), the character played by Madonna, "All the Way" Mae Mordabito, mentions that if the league folds she won't go back to taxi dancing and have guys sweat gin on her for ten cents a dance

- The White Countess (2005), directed by James Ivory, tells the story of a Russian countess (Natasha Richardson) who works as a taxi dancer in Shanghai in 1930s, to support her family of White émigrés; Deadline at Dawn (1946), about a New York dime-a-dance girl helping to clear a sailor framed for murder.

Books

• The Taxi Dancer by Robert Terry Shannon (New York: Edward J. Clade, 1931; A. L. Burt, 1931) • The Confessions of a Taxi Dancer by Anonymous (Detroit: Johnson Smith & Co., 1938) [booklet, 38 pp.] • Taxi Dancers by Eve Linkletter (Fresno, CA: Fabian Books, 1959) (adult paperback) • Crosstown by John Held, Jr. (New York: Dell Books, 1951), "Showgirl Mazie's rise from Taxi-Dancer to Broadway star" • The Adventures of Sally by P. G. Wodehouse (London: Herbert Jenkins, 1939) • Ten Cents a Dance by Christine Fletcher (New York: Bloombury, 2010) • The Bartender's Tale by Ivan Doig (New York: Riverhead Books, 2012), features a character who was formerly a taxi dancer • A Girl Like You: A Henrietta and Inspector Howard Novel by Michelle Cox (Berkeley, CA: She Writes Press, 2016)

Songs

• "Ten Cents a Dance" (1930), music by Richard Rodgers, lyrics by Lorenz Hart • "Taxi War Dance" (1939), jazz instrumental by Count Basie featuring Lester Young • "Aja" (1977), music and lyrics by Steely Dan (refers to "dime dancing") • "Taxi Dancer" (1979), music and lyrics by John Mellencamp. • "Taxi Dancer" (2013) by the band Dengue Fever, "Taxi Dancing" (1984), "Hard to Hold" movie soundtrack, by Rick Springfield featuring Randy Crawford.

Musical Theater

• Simple Simon (1930), music by Richard Rodgers, lyrics by Lorenz Hart, book by Guy Bolton; song "Ten Cents a Dance," sung by Ruth Etting, was introduced in this show • Sweet Charity (1966), music by Cy Coleman, lyrics by Dorothy Fields and book by Neil Simon

Television

- L.A. Law features an episode (5x07) where two of the characters (Benny and Murray) visit a taxi dance hall in Los Angeles during 1990 (despite that apparently being anachronistic).

- Laverne & Shirley has an episode ("Call Me a Taxi" - 1977) where the two are laid off and take jobs as taxi dancers.

- In The Waltons episode "The Achievement" (season 5, episode 25), John-Boy travels to New York to check on his book manuscript, and finds his friend Daisy working as a taxi dancer.

See also

Further reading

- Freeland, David. Automats, Taxi Dances, and Vaudeville: Excavating Manhattan's Lost Places of Leisure. (New York: NYU Press, 2009). ISBN 0814727638.

- McBee, Randy D. Dance Hall Days: Intimacy and Leisure among Working-Class Immigrants in the United States. (New York and London: NYU Press, 2000).

- Cressey, Paul G. The Taxi-Dance Hall: A Sociological Study in Commercialized Recreation and City Life. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1932; 2002). ISBN 9780226120515.

- Stoddard, Tom. Jazz On The Barbary Coast. (Berkeley, CA: Heyday Books, 1982). ISBN 189077104X.

- Montanarelli, Lisa; Harrison, Ann. Strange But True San Francisco: Tales of the City by the Bay. (Guilford, Connecticut: Globe Pequot Press, 2005). ISBN 076273681X.

- Asbury, Herbert. The Barbary Coast: An Informal History of the San Francisco Underworld. (New York: Garden City Publishing Co., 1933; Basic Books, 2002). ISBN 1560254084.

- Knowles, Mark. The Wicked Waltz and Other Scandalous Dances. (Jefferson, North Carolina & London: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2009). ISBN 0786437081.

- Anonymous. Confessions of a Taxi Dancer. (Detroit: Johnson Smith & Co., 1938).

- Ross, Leonard Q. The Strangest Places. (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, Inc., 1939).

- Salerno, Roger A. Sociology Noir: Studies at the University of Chicago in Loneliness, Marginality and Deviance, 1915-1935. (Jefferson, North Carolina & London: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2007).

- Field, Andrew David. Shanghai's Dancing World: Cabaret Culture and Urban Politics, 1919–1954. (Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 2010).

References

- Cressey (1932), pp. 3, 11, 17.

- Burgess, Ernest (1969). "Introduction". The Taxi-Dance Hall: A Sociological Study in Commercialized Recreation and City Life. Montclair, New Jersey: Paterson Smith Publishing. pp. xxviii. ISBN 0875850766.

- Freeland, David. Automats, Taxi Dances, and Vaudeville: Excavating Manhattan's Lost Places of Leisure. (New York: NYU Press, 2009), p. 192.

- Cressey, Paul G. The Taxi-Dance Hall: A Sociological Study in Commercialized Recreation and City Life (Montclair, NJ: Patterson-Smith Publishing Co., 1969), p. 17

- Asbury, Herbert. The Barbary Coast: An Informal History of the San Francisco Underworld. (New York: Basic Books, 2002), p. 3.

- Cressey (1932), p. 179.

- Knowles (1954), p. 64.

- Asbury (1933), p. 99.

- Stoddard, Tom. Jazz On The Barbary Coast. (Berkeley, CA: Heyday Books, 1982), p. 10.

- Stoddard (1982), p. 13.

- Richards, Rand (2002). Historic Walks in San Francisco. San Francisco: Heritage House Publishers. p. 183. ISBN 1879367033.

- Asbury (1933), p. 293.

- Asbury (1933), p. 303.

- Cressey (1932), p. 181.

- Report of Public Dance Hall Committee of San Francisco of California Civic League of Women Voters, p. 14

- Cressey (1932), p. 183.

- Cressey (1932), p. 184.

- Cressey (1932), p. 3.

- Cressey (1932), p. 12.

- Cressey (1932), p. xxxiii.

- VanderKooi, Ronald. University of Illinois at Chicago Circle, March 1969.

- Freeland (2009), p. 190.

- Freeland (2009), p. 194.

- Cressey (1932), p. 182.

- Clyde Vedder: "Decline of the Taxi-Dance Hall," Sociology and Social Research, 1954.

- Fritz, Angela. "I was a Sociological Stranger’: Ethnographic Fieldwork and Undercover Performance in the Publication of The Taxi‐Dance Hall, 1925–1932", Gender & History, Vol. 30, No. 1, March 2018, pp. 131–152.

- Cressey, Paul G. The Taxi-Dance Hall: A Sociological Study in Commercialized Recreation and City Life ((Montclair, NJ: Patterson Smith, 1969), pp. 33–37.

- Kilgannon, Corey. "At $2 a Dance, a Remedy for Loneliness" The New York Times, February 20, 2006.

- Kilgannon (February 20, 2006).

- Wright, Evan. "Dance With A Stranger", LA Weekly, January 20, 1999.

- Strictly tango for the dance tourists, by Uki Goni, The Observer, London, 18 November 2007