The Golden Bird

"The Golden Bird (German: Der goldene Vogel) is a fairy tale collected by the Brothers Grimm (KHM 57) about the pursuit of a golden bird by a gardener's three sons.[1]

| The Golden Bird | |

|---|---|

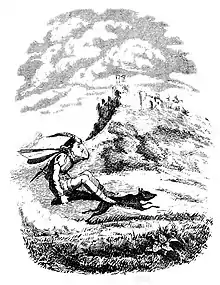

_(14566498237).jpg.webp) The prince and the princess ride on the horse to escape with the caged golden bird, the fox at their side. Illustration from Household stories from the collection of the Bros. Grimm (1914). | |

| Folk tale | |

| Name | The Golden Bird |

| Data | |

| Aarne-Thompson grouping | ATU 550 (The Quest for the Golden Bird; The Quest for the Firebird; Bird, Horse and Princess) |

| Region | Germany |

| Published in | Kinder- und Hausmärchen, by the Brothers Grimm (1812) |

| Related | The Bird 'Grip'; The Greek Princess and the Young Gardener; Tsarevitch Ivan, the Fire Bird and the Gray Wolf; How Ian Direach got the Blue Falcon; The Nunda, Eater of People |

It is Aarne-Thompson folktale type 550, "The Golden Bird", a Supernatural Helper (Animal as Helper). Other tales of this type include The Bird 'Grip', The Greek Princess and the Young Gardener, Tsarevitch Ivan, the Fire Bird and the Gray Wolf, How Ian Direach got the Blue Falcon, and The Nunda, Eater of People.[2]

Origin

A similar version of the story was previously collected in 1808 and published as Der weisse Taube ("The White Dove"), provided by Ms. Gretchen Wild and published along The Golden Bird in the first edition of the Brothers Grimm compilation. In the original tale, the youngest son of the king is known as Dummling,[3] a typical name for naïve or foolish characters in German fairy tales.[4] In newer editions that restore the original tale, it is known as "The Simpleton".[5]

Synopsis

Every year, a king's apple tree is robbed of one golden apple during the night. He sets his gardener's sons to watch, and though the first two fall asleep, the youngest stays awake and sees that the thief is a golden bird. He tries to shoot it, but only knocks a feather off.

The feather is so valuable that the king decides he must have the bird. He sends his gardener's three sons, one after another, to capture the priceless golden bird. The sons each meet a talking fox, who gives them advice for their quest: to choose a bad inn over a brightly lit and merry one. The first two sons ignore the advice and, in the pleasant inn, abandon their quest.

The third son obeys the fox, so the fox advises him to take the bird in its wooden cage from the castle in which it lives, instead of putting it into the golden cage next to it, because this is signal. But he disobeys, and the golden bird rouses the castle, resulting in his capture. He is sent after the golden horse as a condition for sparing his life. The fox advises him to use a leather saddle rather than a golden one which is signal again, but he fails again. He is sent after the princess from the golden castle. The fox advises him not to let her say farewell to her parents, but he disobeys, and the princess's father orders him to remove a hill as the price of his life.

The fox removes it, and then, as they set out, he advises the prince how to keep all the things he has won since then. It then asks the prince to shoot it and cut off its head. When the prince refuses, it warns him against buying gallows' flesh and sitting on the edge of rivers.

He finds that his brothers, who have been carousing and living sinfully in the meantime, are to be hanged (on the gallows) and buys their liberty. They find out what he has done. When he sits on a river's edge, they push him in. They take the things and the princess and bring them to their father. However the bird, the horse, and the princess all grieve for the youngest son. The fox rescues the prince. When he returns to his father's castle dressed in a beggar's cloak, the bird, the horse, and the princess all recognize him as the man who won them, and become cheerful again. His brothers are put to death, and he marries the princess.

Finally, the third son cuts off the fox's head and feet at the creature's request. The fox is revealed to be a man, the brother of the princess.

Analysis

The tale type is characterized by a chain of quests, one after the other, that the hero must fulfill before he takes the prizes to his father. In many variants, the first object is the bird that steals the golden apples from the king's garden; in others, it is a magical fruit or a magical plant, which sets up the next parts of the quest: the horse and the princess.[6]

The animal helper

The helper of the hero differs between versions: usually a fox or a wolf in most versions, but very rarely there is another type of animal, like a lion,[7] a bear[8] or a hare.[9] In some variants, it is a grateful dead who helps the hero as retribution for a good deed of the protagonist.[10]

In a variant collected in Austria, by Ignaz and Joseph Zingerle (Der Vogel Phönix, das Wasser des Lebens und die Wunderblume, or "The Phoenix Bird, the Water of Life and the Most beautiful Flower"),[11] the tale begins with the motif of the birth of twin wonder-children, akin to The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird. Cast away from home, the twins grow up and take refuge in their (unbeknownst to them) father's house. Their aunt asks for the titular items, and the fox who helps the hero is his mother's reincarnation.[12]

In a Polish variant by Oskar Kolberg, O królewiczu i jego przyjacielu, kruku ("About the prince and his friend, the Raven"), a raven, sent by a mysterious hermit, helps a prince in his quest for a golden bird. This variant is peculiar in that the princess is the second-to-last object of the quest, and the horse the last.[13]

The bird as the object of the quest

The character of the Golden Bird has been noted to resemble the mythological phoenix bird.[14] Indeed, in many variants the hero quests for the Phoenix bird.[15]

The Golden Bird of the Brothers Grimm tale can be seen as a counterpart to the Firebird of Slavic folklore, a bird said to possess magical powers and a radiant brilliance, in many fairy tales.[16] The Slavic Firebird can also be known by the name Ohnivak[17] Zhar Bird[18] or Bird Zhar;[19] Glowing Bird,[20] or The Bird of Light.[21]

Sometimes, the king or the hero's father send the hero on his quest for the bird to cure him of his illness or blindness, instead of finding out who has been destroying his garden and/or stealing his precious golden apples.[22] Under this lens, the tale veers close to ATU 551, "The Water of Life" (The Sons on a quest for a wonderful remedy for their father), also collected by the Brothers Grimm.[23]

In many variants, the reason for the quest is to bring the bird to decorate a newly-built church,[24] temple or mosque,[25] as per the suggestion of a passing beggar or hermit that informed the king of its existence.[26][27][28]

In 20th century Dutch collections, the bird is sometimes called Vogel Vinus or Vogel Venus. Scholarship suggests that the name is a corruption of the name Phönix by the narrators.[29] The name also appears in the 19th century Hungarian tale A Vénus madara ("The Bird Venus").[30]

In a variant published by illustrator Howard Pyle, The White Bird, the prince takes part in a chain of quests: for the Fruit of Happiness, the Sword of Brightness and the titular White Bird. When the prince captures the White Bird, it transforms into a beautiful princess.[31]

In the Hungarian variant Az aranymadár ("The Golden Bird"), the king wants to own a fabled golden bird. A prince captures the bird and it reveals it is a princess cursed into the avian form by a witch.[32]

The horse as the object of the quest

The horse of the variants of the tale is sometimes referenced along with the bird, attached to a special trait, such as in Flemish versions Van de Gouden Vogel, het Gouden Peerde en de Prinses,[33] and Van de wonderschoone Prinses, het zilveren Paardeken en de gouden Vogel,[34] and in French-Flanders version Van Vogel Venus, Peerdeken-Muishaar en Glooremonde.[35]

The horse, in many variants of the tale, is the means by which the hero escapes with the princess. In one Italian variant, the horse is described as irraggiungibile ("unreachable").[36]

In the Hungarian variant A vak király ("The Blind King"), the youngest prince, with the help of a fox, joins the quest for the golden bird and the silver-coloured horse with golden hair.[37]

The princess as the object of the quest

In the title of many variants, the Princess as the last object the hero's quest is referenced in the title. The tales usually reference a peculiar characteristic or special trait, such as in Corsican variant La jument qui marche comme le vent, l'oiseau qui chante et joue de la musique et la dame des sept beautés (Corsican: "A jumenta chi biaghja quant'u ventu, l'agellu chi canta e chi sona, a donna di sette bellezze"; English: "The she-donkey that rides like the wind, the bird that sings and plays music, and the maiden of seven beauties"), collected by Genevieve Massignon.[38]

In Italian variant L'acqua di l'occhi e la bella di setti veli ("The water for the eyes and the beauty with seven veils"), the prince is sent on a quest for "l'acqua di l'occhi", the beauty with seven veils, the talking horse and the "aceddu Bonvirdi" (a kind of bird).[39]

In Romanian variant Pasărea cîntă, domnii dorm, the emperor asks for the golden bird whose song makes men sleep. His son travels the lands for the fabled bird, and discovers its owner is the princess of the golden kingdom.[40]

In Hungarian variant A próbára tett királyfi ("The king's son put to the test"), in the final part of the quest, the prince is tasked with kidnapping a fairy princess from her witch mother. With his faithful fox companion, which transforms into a replica of the fairy maiden to trick her mother, the prince obtains the fairy maiden.[41]

In a tale collected by Andrew Lang and attributed to the Brothers Grimm, The Golden Mermaid, the king's golden apples are stolen by some creature or thief, so he sends his sons to find it. The youngest son, however, is the only one successful: he discovers the thief is a magic bird that belongs to an Emperor; steals a golden horse and obtains the titular golden mermaid as his wife.[42]

Variants

It has been noted that the tale "is told in Middle East and in Europe",[43] but its variants are present in traditions from the world over,[44] including India, Indonesia and Central Africa.[45]

Swedish folktale collectors George Stephens and Gunnar Olof Hyltén-Cavallius suggested an Eastern origin for the story.[46]

Literary history

Scholars Stith Thompson, Johannes Bolte and Jiří Polívka traced a long literary history of the tale type:[47] an ancient version is attested in The Arabian Nights.[48]

A story titled Sagan af Artus Fagra is reported to contain a tale of three brothers, Carolo, Vilhiamo and Arturo of the Fagra clan, sons of the King of the Angles, who depart to India on a quest for the Phoenix bird to heal their father.[49] It was published in an Icelandic manuscript of the 14th century.[50][51] Swedish folktale collectors George Stephens and Gunnar Olof Hyltén-Cavallius listed Danish tale Kong Edvard och Prints Artus,[52] collected in 1816, as a story related to Sagan of Artus Fagra.[53]

Dutch scholarship states that a Flemish medieval manuscript from the 11th century, Roman van Walewein (en het schaakspel) (English: "The Romance of Walewein (and the chessboard)") (nl), is an ancestor of the ATU 550 tale type.[54][55]

Scholars Willem de Blecourt and Suzanne Magnanini indicate as a literary version a tale written by Lorenzo Selva, in his Metamorfosi: an illegitimate son of a king searches for the Pistis, a plant with healing powers. Later, he is forced to seek the maiden Agape, a foreign princess from a distant land, and a winged horse to finish the quest.[56][57]

An almost immediate predecessor to the Grimms' tale was published in 1787, in an anonymous compilation of fairy tales. In this story, Der treue Fuchs ("The loyal fox"), the youngest son of King Romwald, Prince Nanell, shares his food with a fox and the animal helps him acquire the Phoenix bird, the "bunte Pferdchen" ("colored horse") and the beautiful Trako Maid. The publisher was later identified as Wilhelm Christoph Günther (de).[58]

France

A French version, collected by Paul Sébillot in Littérature orale de la Haute-Bretagne, is called Le Merle d'or (The Golden Blackbird). Andrew Lang included that variant in The Green Fairy Book (1892).[59][60] In The Golden Blackbird, the gardener's son set out because the doctors have prescribed the golden blackbird for their ill father. The two older brothers are allured into the inn without any warning, and the youngest meets the talking hare that aids him only after he passes it by. The horse is featured only as a purchase, and he did not have to perform two tasks to win the Porcelain Maiden, the princess figure. Also, the hare is not transformed at the end of the tale.[61]

Another version, collected by François-Marie Luzel, is called Princess Marcassa and the Dreadaine Bird. There, the man sick in a king rather than a gardener, and the fox isn't the brother of the princess, but the soul of a poor old man whom the prince, after being robbed by his older brothers, buries with the last of his money. The prince, while stealing the bird, impregnates the princess as she's asleep, and it's the child's insistence on finding his father which makes the princess follow him and reveal the truth.

Western Europe

In a "Scottish-Tinker" tale, The Fox, Brian, the son of the King of Greece, in order to marry the hen's wife, must quest for "the most marvellous bird" in the world, the White Glaive of Light and the Sun Goddess, "daughter of the king of the gathering of Fionn". He is helped in his tasks by a fox, which is the Sun Goddess's brother transformed.[62]

An Irish variant of the type, published in 1936 (Le roi magicien sous la terre), seems to contain the Celtic motif of "the journey to the Other World".[63]

Southern Europe

In a Galician tale, O Páxaro de Ouro, the king owns an orchard where there is a tree with red Portuguese apples that are stolen by the titular golden bird.[64]

A scholarly inquiry by Italian Istituto centrale per i beni sonori ed audiovisivi ("Central Institute of Sound and Audiovisual Heritage"), produced in the late 1960s and early 1970s, found thirteen variants of the tale across Italian sources, under the name La Ricerca dell'Uccello d'Oro.[65]

Germany

Folklorist Jeremiah Curtin noted that the Russian, Slavic and German variants are many,[66] such as Die drei Gärtnerssöhne ("The gardener's three sons");[67] or Der Goldvogel, das Goldpferd und die Prinzeßin, by German theologue Johann Andreas Christian Löhr.[68]

In the Plattdeutsche (Low German) variant collected by Wilhelm Wisser, Vagel Fenus, the protagonist searches for the bird Fenus because his father dreamt that it could restore his health,[69] while in the tale De gollen Vagel, the tale begins with the usual vigil at the garden to protect the tree of golden apples.[70]

In a variant from Flensburg, Guldfuglen ("Goldbird"), the gardener's youngest son, with the help of a fox, searches for the White Hart and the "White Maiden" ("hivde Jomfru").[71]

Romania

In a Romanian variant, Boy-Beautiful, the Golden Apples, and the Were-Wolf, the sons of the emperor investigate who has been eating the emperor's prized apples, and the youngest prince (possibly Făt-Frumos) finds two shining golden feathers in the foliage.[72]

In Romanian variant Povestea lupului năsdrăvan şi a Ilenei Cosinzene, a wolf helps the prince in his quest for the feather of a golden dove, a golden apple, a horse and the legendary princess Ileana Cosânzeana. When the king's other sons kill the prince, the apple wilts, the dove becomes a black raven and the horse and the princess vanish into the sky.[73]

In another tale, The Wonderful Bird (Pasărea măiastră (ro)), the king sends his sons for a bird to decorate a newly built church. His elder sons return with the bird and a poultry maid, the bird does not sing and the maid seems to be despondent. The youngest prince returns incognito to his father's kingdom and tells his story: the bird begins to sing when the prince enters the church, recognizing its master.[74]

Eastern Europe

In a Polish variant, About Jan the Prince, the fabled bird is named The Flamebird.[75] The tale was originally collected by Antoni Josef Glinski, with the title O Janie królewiczu, żar-ptaku i o wilku wiatrolocie ("About Jan the Prince, the Flamebird and the Wind-like Wolf").[76]

In a Yugoslavian variant, The Little Lame Fox, Janko, the naive but good-hearted youngest son of a farmer, is helped by a fox in his quest for the Golden Apple-Tree, the Golden Horse, the Golden Cradle and the Golden Maiden. The Golden Maiden, a princess herself, insists that she will marry Janko, for his good and brave heart.[77]

In a Hungarian tale, A csodás szőlőtő ("The Wonderful Grapevine"), three princes ask his father, the king, why one of his eyes laughs while the other cries. This prompts a quest for the king's lost grapevine and, later, for a horse and a princess.[78]

Scandinavian

Variants from Scandinavian countries have been attested in the works of Svend Grundtvig (Danish variant "The Golden Bird" or Guldfuglen)[79][80] and Peter Asbjornsen (Norwegian variant "The Golden Bird" or Gullfuglen).[81][82][83]

Baltic Countries

August Leskien collected variants from Lithuania, where the wolf is the helper, akin to Slavic variants: Vom Dummbart und dem Wolf, der sein Freund war[84] and a similarly named tale where the apples are made of diamond and the bird is a falcon,[85] and Von den drei Königssöhnen.

Latvia

In a Latvian variant collected in 1877, "одарѣ раскрасавицѣ царевић и братѣдуракѣ съ его помощниками" ("The talented princes, the foolish brother and his helpers"), the king sets a deadline for his three sons: one year from now, they must capture and bring him the golden bird that ate his golden apples. The youngest son is the only one that soldiers on, and eventually captures the bird, two dogs, a steed and a princess.[86] Fricis Brīvzemnieks, in the same book, gave an abridged summary of two other variants: in one, the prince abducts a princess with golden hair, eyes like dew and fingernails like diamonds,[87] and in the other, when the prince captures the golden bird, it uses its power to revive the older brothers who were petrified.[88]

Asia

In an Indian variant, In Search of a Dream, the youngest prince quests for an emerald bird, because his father, the king, had a dream about a beautiful garden, with a tree in it where the bird was perched. Apart from this tale, Indian scholar A. K. Ramanujan pointed the existence of twenty-seven variants collected from all over India.[89]

In a Tatar tale collected in Tobolsk, Der den Vogel suchende Fürstensohn ("The Prince's Son that seeks the bird"), the prince's youngest son watches his father's house at night and finds a bird. Soon, he travels to capture the bird and bring it home. With the help of a wolf, he later steals seven wonderful horses and a golden cithara from two different foreign princes and finally abducts a princess from a fourth realm.[90]

Americas

A similar variant fairy tale of French-Canadian origin is The Golden Phoenix collected by Marius Barbeau, and retold by Michael Hornyansky. It follows the hero Petit Jean, the youngest son of the King, who discovers the thief of his father's golden apple to be a golden Phoenix, a legendary bird. Other differences include a battle with 3 mythical beasts, a Sultan's game of hide-and-seek and his marriage with the Sultan's beautiful daughter.

Variants have been recorded from American regions and states: a version named The Golden Duck from West Virginia;[91] a tale The King's Golden Apple Tree, from Kentucky;[92] a version from the American Southwest.[93]

J. Alden Mason collected a variant from Mexico, titled Cuento del Pájaro del Dulce Canto (English: "The Bird of the Sweet Song").[94]

In a Brazilian variant collected by Silvio Romero in Sergipe, A Raposinha (English: "The little fox"), a prince stops three men from beating a dead person, and in gratitude is helped by a fox in his search for a parrot from the Kingdom of Parrots as a cure for the king's blindness.[95]

Literary versions

French author Edouard Laboulaye included a literary version named The Three Wonders of the World in his book Last Fairy Tales: the queen wishes for a magical bird that can rejuvenate people with its song. The youngest prince also acquires the winged horse Griffon and a wife for himself, the princess Fairest of the Fair.[96]

Italian author Luigi Capuana used the motif of the golden-coloured bird stealing the apples in his literary fiaba Le arance d'oro ("The Golden Apples"),[97] where a goldfinch is sent to steal the oranges in the King's orchard.[98][99]

Professor Jack Zipes states that the tale type inspired Russian poet Pyotr Pavlovich Yershov to write his fairy tale poem The Little Humpbacked Horse. The tale begins akin to ATU 530, "The Princess on the Glass Mountain", (hero finds or captures wild horse(s) with magical powers) and continues as ATU 550: the envious Tsar asks the peasant Ivan to bring him the firebird and the beautiful Tsar-Maid.[100]

A literary treatment of the tale exists in The True Annals of Fairy-Land: The Reign of King Herla, titled The Golden Bird: with the help of friendly fox, the king's youngest son ventures to seek the Golden Bird, the Golden Horse and a princess, the Beautiful Daughter of the King of the Golden Castle. At the conclusion of the tale, the fox is revealed to be the Princess's brother, transfomed into a vulpine shape.[101]

Czech school teacher Ludmila Tesařová (cs) published a literary version of the tale, named Pták Zlatohlav, wherein the knight quests for the golden-headed bird whose marvellous singing can cure an ailing princess.[102]

Adaptations

A Hungarian variant of the tale was adapted into an episode of the Hungarian television series Hungarian Folk Tales (Magyar népmesék). It was titled The Fox Princess (A rókaszemü menyecske).[103]

See also

- Ibong Adarna

- Laughing Eye and Weeping Eye

- Prâslea the Brave and the Golden Apples

- The Bold Knight, the Apples of Youth, and the Water of Life

- The Brown Bear of the Green Glen

- The Golden-Headed Fish

- The King of England and his Three Sons

- The Nine Peahens and the Golden Apples

- The Sister of the Sun

- The Story of Bensurdatu

- The Water of Life

- The Little Green Frog (French literary fairy tale)

References

- Ashliman, D. L. (2020). "Grimm Brothers' Children's and Household Tales (Grimms' Fairy Tales)". University of Pittsburgh.

- "SurLaLune Fairy Tales: Tales Similar To Firebird". surlalunefairytales.com.

- Bolte, Johannes; Polívka, Jiri. Anmerkungen zu den Kinder- u. hausmärchen der brüder Grimm. Erster Band (NR. 1-60). Germany, Leipzig: Dieterich'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung. 1913. pp. 503-504.

- Grimm, Jacob & Grimm, Wilhelm; Taylor, Edgar; Cruikshank, George (illustrator). Grimm's Goblins: Grimm's Household Stories. London: R. Meek & Co.. 1877. p. 289.

- Grimm, Jacob, Wilhelm Grimm, JACK ZIPES, and ANDREA DEZSÖ. "THE SIMPLETON." In The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: The Complete First Edition, 207-15. Princeton; Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2014. Accessed August 13, 2020. doi:10.2307/j.ctt6wq18v.71.

- Sorlin, Evelyne. "Le Thème de la tristesse dans les contes AaTh 514 et 550". In: Fabula 30, Jahresband (1989): 285-288. doi: https://doi.org/10.1515/fabl.1989.30.1.279

- "Der Goldvogel". In: Löwis of Menar, August von. Finnische und estnische Volksmärchen. Jena: Eugen Diederichs. 1922. pp. 12-16.

- "Der Vogel Phönix". In: Wolf, Johann Wilhelm. Deutsche Hausmärchen. Göttingen/Leipzig: 1851. pp. 229-242.

- "The Golden Bird and the Good Hare". In: Groome, Francis Hindes. Gypsy folk-tales. London: Hurst and Blackett. 1899. pp. 182-187.

- Bolte, Johannes; Polívka, Jiri. Anmerkungen zu den Kinder- u. hausmärchen der brüder Grimm. Erster Band (NR. 1-60). Germany, Leipzig: Dieterich'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung. 1913. pp. 503-515.

- Zingerle, Ignaz und Zingerle, Joseph. Kinder- und Hausmärchen aus Süddeutschland. Regensburg: F. Pustet. 1854. pp. 157-172.

- The Pleasant Nights. Volume 1. Edited with Introduction and Commentaries by Donald Beecher. Translated by W. G. Waters. University of Toronto Press. 2012. p. 598. ISBN 978-1-4426-4426-7

- Kolberg, Oskar. Lud: Jego zwyczaje, sposób życia, mowa, podania, przysłowia, obrzędy, gusła, zabawy, pieśni, muzyka i tańce. Serya VIII. Kraków: w drukarni Dr. Ludwika Gumplowicza. 1875. pp. 48-52.

- Grimm, Jacob & Grimm, Wilhelm; Taylor, Edgar; Cruikshank, George (illustrator). Grimm's Goblins: Grimm's Household Stories. London: R. Meek & Co.. 1877. p. 289.

- Bolte, Johannes; Polívka, Jiri. Anmerkungen zu den Kinder- u. hausmärchen der brüder Grimm. Erster Band (NR. 1-60). Germany, Leipzig: Dieterich'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung. 1913. pp. 503-515.

- Ralston, William Ralston Shedden. Russian fairy tales: a choice collection of Muscovite folk-lore. New York: Pollard & Moss. 1887. pp. 288-292.

- Harding, Emily J. Fairy tales of the Slav peasants and herdsmen. London: G. Allen. 1886. pp. 265-292.

- Pyle, Katherine. Fairy Tales of Many Nations. New York: E.P. Dutton & Co. 1911. pp. 118-139.

- Bain, R. Nisbet. Cossack fairy tales and folk tales. London : G.G. Harrap & Co.. 1916. pp. 95-104.

- "Tzarevich Ivan, the Glowing Bird and the Grey Wolf" In: Wheeler, Post. Russian wonder tales: with a foreword on the Russian skazki. London: A. & C. Black. 1917. pp. 93-118.

- Russian Folk-Tales by Alexander Nikolaevich Afanasyev. Translated by Leonard Arthur Magnus.New York: E. P. Dutton and Company. 1916. pp. 78-90.

- Bolte, Johannes; Polívka, Jiri. Anmerkungen zu den Kinder- u. hausmärchen der brüder Grimm. Erster Band (NR. 1-60). Germany, Leipzig: Dieterich'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung. 1913. pp. 503-515.

- Hyltén-Cavallius, Gunnar Olof och Stephens, George. Svenska Folk-Sagor och Äfventyr. Förste Delen. Stockholm: pa A. Bohlins Förlag. 1844. pp. 151-152.

- Pop-Reteganul, Ion. (in Romanian) – via Wikisource.

- "The Nightingale in the Mosque". In: Fillmore, Parker. The Laughing Prince: a Book of Jugoslav Fairy Tales And Folk Tales. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1921. pp. 171-200.

- "Der Prinz und der Wundervogel". In: Heller, Lotte. Ukrainische Volksmärchen; uebertragen und erzählt von Lotte Heller und Nadija Surowzowa. Illustriert von Jury Wowk. Wien: Rikola Verlag. 1921. pp. 55-63.

- "The Fairy Nightingale". In: Seklemian, A. G. The Golden Maiden and Other Folk Tales and Fairy Stories Told in Armenia. Cleveland and New York: The Helman-Taylor Company. 1898. pp. 33-39.

- "Der goldne Vogel". In: Haltrich, Joseph. Deutsche Volksmærchen aus dem Sachsenlande in Siebenbürgen. Berlin: 1856. pp. 31-39.

- Meder, Theo. "De gouden vogel (vuurvogel)". In: Van Aladdin tot Zwaan kleef aan. Lexicon van sprookjes: ontstaan, ontwikkeling, variaties. 1ste druk. Ton Dekker & Jurjen van der Kooi & Theo Meder. Kritak: Sun. 1997. p. 152.

- György Gaal. Gaal György magyar népmesegyujteménye (3. kötet). Pesten: Emich Gusztáv Sajátja. 1860. pp. 1-14.

- Pyle, Howard; Pyle, Katharine. The Wonder Clock: Or, Four & Twenty Marvellous Tales, Being One for Each Hour of the Day. New York: Printed by Harper & Brothers. 1915 (1887). pp. 107-120.

- György Gaal. Gaal György magyar népmesegyujteménye (2. kötet). Pesten: Pfeifer Ferdinánd Sajátja. 1857. pp. 149-156.

- Vervliet, J. B.; Cornelissen, Jozef. Vlaamsche volksvertelsels en kindersprookjes. Lier: Jozef VAN IN & Cie, Drukkers-Uitgevers. 1900. pp. 36-42.

- de Meyere, Victor. De Vlaamsche vertelselschat. Deel 3. 1ste druk. 1929. pp. 103-111.

- de Meyere, Victor. De Vlaamsche vertelselschat. Deel 3. 1ste druk. 1929. p. 305.

- Di Francia, Letterio (Curatore). Fiabe e novelle calabresi. Prima e seconda parte. Torino: Giovanni Chiantore, 1935. pp. 196-198.

- László Arany. Eredeti népmesék. Pest: Kiadja Heckenast Gusztáv. 1862. pp. 1-29.

- Massignon, Genevieve. Contes corses. Paris: Picarde. 1984 [1963]. pp. 7-10. ISBN 2-7084-0102-5

- Di Francia, Letterio (Curatore). Fiabe e novelle calabresi. Prima e seconda parte. Torino: Giovanni Chiantore, 1935. pp. 181-195.

- Pop-Reteganul, Ion. (in Romanian) – via Wikisource.

- János Berze Nagy. Népmesék Heves- és Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok-megyébol (Népköltési gyüjtemény 9. kötet). Budapest: Az Athenaeum Részvény-Társulat Tulajdona. 1907. pp. 72-80.

- Lang, Andrew. The Green Fairy Book. Longmans, Green. 1892. pp. 328-338.

- Ramanujan, A. K. A Flowering Tree and Other Oral Tales from India. Berkeley London: University of California Press. 1997. p. 248. ISBN 0-520-20398-4

- Elijah's Violin and Other Jewish Fairy Tales. Selected and retold by Howard Schwartz. New York, Oxford: The Oxforn University Press. 1994 [1983]. p. 301. ISBN 0-19-509200-7

- Garry, Jane. "Choice of Roads. Motif N122.0.1, and Crossroads, Various Motifs". In: Jane Garry and Hasan El-Shamy (eds.). Archetypes and Motifs in Folklore and Literature. A Handbook. Armonk / London: M.E. Sharpe, 2005. p. 334.

- Hyltén-Cavallius, Gunnar Olof och Stephens, George. Svenska Folk-Sagor och Äfventyr. Förste Delen. Stockholm: pa A. Bohlins Förlag. 1844. p. 151

- Thompson, Stith (1977). The Folktale. University of California Press. p. 107. ISBN 0-520-03537-2.

- Dégh, Linda. Folktales and Society: Story-telling in a Hungarian Peasant Community. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. 1989 [1969]. p. 331. ISBN 0-253-31679-0

- Grimm, Jacob & Grimm, Wilhelm; Taylor, Edgar; Cruikshank, George (illustrator). Grimm's Goblins: Grimm's Household Stories. London: R. Meek & Co.. 1877. p. 289.

- The Complaynt of Scotland: Written in 1548. With Preliminary Dissertantion and Gossary. Edinburgh: 1801. p. 237.

- Jacob & Wilhelm Grimm; Zipes, Jack; Dezsö, Andrea (illustrator). The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: The Complete First Edition Princeton; Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2014. p. 497. Accessed August 12, 2020. doi:10.2307/j.ctt6wq18v.166.

- Nyerup, Rasmus. Almindelig Morskabslæsning i Danmark og Norge igjennem Aarhundreder. Kjøbenhavn: 1816. pp. 227-230.

- Hyltén-Cavallius, Gunnar Olof och Stephens, George. Svenska Folk-Sagor och Äfventyr. Förste Delen. Stockholm: pa A. Bohlins Förlag. 1844. p. 151.

- Meder, Theo. "De gouden vogel (vuurvogel)". In: Van Aladdin tot Zwaan kleef aan. Lexicon van sprookjes: ontstaan, ontwikkeling, variaties. 1ste druk. Ton Dekker & Jurjen van der Kooi & Theo Meder. Kritak: Sun. 1997. pp. 152-153.

- Ker, W. P. "The Roman Van Walewein (Gawain)." Folklore 5, no. 2 (1894): 121-28. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1253647.

- Magnanini, Suzanne. "Between Straparola and Basile: Three Fairy Tales from Lorenzo Selva's Della Metamorfosi (1582)." Marvels & Tales 25, no. 2 (2011): 331-69. Accessed November 29, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41389007.

- De Blécourt, Willem. "A Quest for Rejuvenation." In: Tales of Magic, Tales in Print: On the Genealogy of Fairy Tales and the Brothers Grimm. p. 61. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2012. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv6p4w6.7.

- Günther, Christopher Wilhelm. Kindermärchen Aus Mündlichen Erzählungen Gesammelt. 2e aufl. Jena: F. Frommann, 1857. pp. 93-150.

- "THE GOLDEN BLACKBIRD from Andrew Lang's Fairy Books". mythfolklore.net.

- Le Merle d'or, by Paul Sébillot, on French Wikisource.

- Wiggin, Kate Douglas Smith; Smith, Nora Archibald. Magic casements: a second fairy book. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, Doran & Co.. 1931 [1904]. pp. 245-250.

- Groome, Francis Hindes. Gypsy folk-tales. London: Hurst and Blackett. 1899. pp. 283-289.

- Sjœstedt-Jonval, Marie-Louise. "An Craoibhinn Aoibhinn (Douglas Hyde), Ocht sgéalta o Choillte Mághach. Dublin, Educational Co., 1936" [compte-rendu]. In: Etudes Celtiques, vol. 2, fascicule 3, 1937. pp. 142-144. www.persee.fr/doc/ecelt_0373-1928_1937_num_2_3_1137_t2_0142_0000_2

- Carre Alvarelllos, Lois. Contos Populares da Galiza. Porto: Museu de Etnografia de Porto. 1968. pp. 25-30.

- Discoteca di Stato (1975). Alberto Mario Cirese; Liliana Serafini (eds.). Tradizioni orali non cantate: primo inventario nazionale per tipi, motivi o argomenti [Oral and Non Sung Traditions: First National Inventory by Types, Motifs or Topics] (in Italian and English). Ministero dei beni culturali e ambientali. p. 146.

- Curtin, Jeremiah. Myths and Folk-tales of the Russians, Western Slavs, and Magyars. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company. 1890. p. 349.

- Lehnert, Johann Heinrich. Mährchenkranz für Kinder, der erheiternden Unterhaltung besonders im Familienkreise geweiht. Berlin [1829]. CXLVIII-CLV (148-155).

- Löhr, Johann Andreas Christian. Das Buch der Maehrchen für Kindheit und Jugend, nebst etzlichen Schnaken und Schnurren, anmuthig und lehrhaftig [1–]2. Band 2, Leipzig [ca. 1819/20]. pp. 248-257.

- Wisser, Wilhelm. Plattdeutsche Volksmärchen. Jena: Verlegt bei Euden Diederichs. 1922. pp. 156-162.

- Wisser, Wilhelm. Plattdeutsche Volksmärchen. Jena: Verlegt bei Euden Diederichs. 1922. pp. 163-170.

- Madsen, Jens. Folkeminder fra Hanved Sogn ved Flensborg. Kjobenhavn: i komission C. S. Ivensens Boghandel. 1870. pp. 3-7.

- Kúnos, Ignácz; Bain, R. Nisbet (translator). Turkish fairy tales and folk tales. New York: Frederick A. Stokes Company. [1896] pp. 244-259.

- Vasiliu, Alexandru. Poveşti şi legende culese de Alexandru Vasiliu. Învăţător în Tătăruşi (Suceava). Academia Română din viaţa poporului român XXXVI. Cultura Naţională: 1927.

- Kremnitz, Mite, and Mary J Safford. Roumanian Fairy Tales. New York: H. Holt and company. 1885. pp. 16-29.

- Byrde, Elsie. The Polish Fairy Book. London: T. Fisher Unwin LTD. 1925. pp. 85-102.

- Gliński, Antoni Józef. Bajarz polski: Baśni, powieści i gawędy ludowe. Tom I. Wilno: W Drukarni Gubernialnéj. 1862. pp. 15-38.

- Fillmore, Parker. The Laughing Prince: a Book of Jugoslav Fairy Tales And Folk Tales. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1921. pp. 73-106.

- Arnold Ipolyi. Ipolyi Arnold népmesegyüjteménye (Népköltési gyüjtemény 13. kötet). Budapest: Az Athenaeum Részvénytársualt Tulajdona. 1914. pp. 118-132.

- Grundtvig, Svend. Danske Folkeæventyr ved Svend Grundtvig. Kjobenhavn: Forlagt af Aug. Bahg og Lehmann & Stage. Trykt Hos J. Jorgensen & Co. 1884. pp. 102-124.

- Hatch, Mary Cottam; Grundtvig, Sven. More Danish tales. New York: Harcourt, Brace. 1949. pp. 214-237.

- Asbjørnsen, Peter Christen. Norske Folke-eventyr: Ny samling. Christiania: I kommission hos J. Dybwad, 1871. pp. 108-116.

- Asbjørnsen, Peter Christen; Dasent, George Webbe. Tales from the fjeld: a series of popular tales from the Norse of P. Ch. Asbjørnsen. London: Gibbings; New York: G.P. Putnam's. 1896. pp. 391-403.

- Asbjørnsen, Peter Christen; Brækstad, Hans Lien (translator). Fairy tales from the far North. London: David Nutt. 1897. pp. 8-19.

- Leskien, August/Brugman, K. Litauische Volkslieder und Märchen. Straßburg: Karl J. Trübner, 1882. pp. 363-371.

- Leskien, August/Brugman, K. Litauische Volkslieder und Märchen. Straßburg: Karl J. Trübner, 1882. pp. 371-375.

- Brīvzemnieks, Fricis. Латышскія народныя сказки. Moskva: 1877. pp. 211-222. (In Russian [pre-1918 grammatical reform])

- Brīvzemnieks, Fricis. Латышскія народныя сказки. Moskva: 1877. pp. 223-227 (footnote nr. 1). (In Russian [pre-1918 grammatical reform])

- Brīvzemnieks, Fricis. Латышскія народныя сказки. Moskva: 1877. pp. 227-229 (continuation of footnote nr. 1). (In Russian [pre-1918 grammatical reform])

- Ramanujan, A. K. A Flowering Tree and Other Oral Tales from India. Berkeley London: University of California Press. 1997. pp. 91-94 and 248. ISBN 0-520-20398-4

- Radlov, Vasiliĭ Vasilʹevich. Proben der volkslitteratur der türkischen stämme. IV. Theil: Dir Mundarten der Baradiner, Taraer, Toboler und Tümenischen Tataren. St. Petersburg: Commisionäre der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften. 1872. pp. 146-154.

- Musick, Ruth Ann. Green Hills of Magic: West Virginia Folktales from Europe. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky. 1970. pp. 174-185. ISBN 978-0-8131-1191-9

- Campbell, Marie. Tales from the Cloud-Walking Country. Athens and London: The University of Geogia Press. 2000 [1958]. pp. 70-77. ISBN 0-8203-2186-9

- Campa, Arthur L. "Spanish Traditional Tales in the Southwest." In: Western Folklore 6, no. 4 (1947): 322-34. Accessed October 11, 2020. doi:10.2307/1497665.

- American Folklore Society. Journal of American Folklore. Vol. 25. Washington [etc.]: American Folklore Society, 1912. pp. 194-195.

- Romero, Silvio. Contos populares do Brazil. São Paulo: Livraria de Francisco Alves. 1897. pp. 28-31.

- Laboulaye, Edouard; Booth, Mary Louise). Last fairy tales. New York: Harper & Brothers. [ca. 1884] pp. 1-36.

- Underhill, Zoe Dana. The Dwarfs' Tailor, And Other Fairy Tales. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers. 1896. pp. 164-176.

- Capuana, Luigi. C'era una volta...: Fiabe. Milano: Fratelli Treves, Editori. 1885. pp. 57-73.

- Capuana, Luigi. Once upon a time fairy tales. New York: Cassell Publishing Company. 1893. pp. 16-28.

- Zipes, Jack (2019). "Speaking the Truth with Folk and Fairy Tales: The Power of the Powerless". The Journal of American Folklore. 132 (525): 243–259. doi:10.5406/jamerfolk.132.525.0243. JSTOR 10.5406/jamerfolk.132.525.0243.

- The true annals of fairy-land: the reign of King Herla. Edited by William Canton; illustrated by Charles Robinson. London: J.M. Dent & Co. [1900] pp. 96-105.

- TESAŘOVÁ, Ludmila. "Za kouzelnou branou: původní české pohádky". Ilustroval Artuš Scheiner. Praha: Weinfurter, 1932. pp. 24-32.

- "Animated Hungarian folk tales". Magyar népmesék (TV Series 1980-2012). Magyar Televízió Müvelödési Föszerkesztöség (MTV) (I), Pannónia Filmstúdió. 18 September 1980. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

Bibliography

- Bolte, Johannes; Polívka, Jiri. Anmerkungen zu den Kinder- u. hausmärchen der brüder Grimm. Erster Band (NR. 1-60). Germany, Leipzig: Dieterich'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung. 1913. pp. 503–515.

- Cosquin, Emmanuel. Contes populaires de Lorraine comparés avec les contes des autres provinces de France et des pays étrangers, et précedés d'un essai sur l'origine et la propagation des contes populaires européens. Tome I. Paris: Vieweg. 1887. pp. 212–222.

- Hyltén-Cavallius, Gunnar Olof och Stephens, George. Svenska Folk-Sagor och Äfventyr. Förste Delen. Stockholm: pa A. Bohlins Förlag. 1844. pp. 151–152 and 164-168.

- Hyltén-Cavallius, Gunnar Olof och Stephens, George. Svenska Folk-Sagor och Äfventyr. Förste Delen. Stockholm: pa A. Bohlins Förlag. 1849. pp. 488–489.

- Schott, Arthur and Schott, Albert. Walachische Maehrchen. Stuttgart: J. G. Cotta. 1845. pp. 368–370.

Further reading

- Blecourt, Willem. (2008). 'The Golden Bird', 'The Water of Life' and the Walewein. Tijdschrift Voor Nederlandse Taal-en Letterkunde. 124. 259-277.

- De Blécourt, Willem. "A Quest for Rejuvenation." In: Tales of Magic, Tales in Print: On the Genealogy of Fairy Tales and the Brothers Grimm. pp. 51–79. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2012. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv6p4w6.7.

External links

Works related to The Golden Bird at Wikisource

Works related to The Golden Bird at Wikisource Media related to The Golden Bird at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to The Golden Bird at Wikimedia Commons- The Golden Blackbird, a fairytale interpretation following v. Franz's school

- A rókaszemü menyecske at IMDb