The Littlest Rebel

The Littlest Rebel is a 1935 American drama film directed by David Butler. The screenplay by Edwin J. Burke was adapted from a play of the same name by Edward Peple and focuses on the tribulations of a plantation-owning family during the American Civil War. The film stars Shirley Temple, John Boles, and Karen Morley, as the plantation family and Bill Robinson as their slave with Jack Holt as a Union officer.

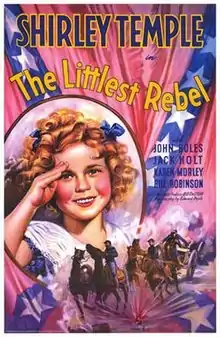

| The Littlest Rebel | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | David Butler |

| Produced by | Darryl Zanuck (producer) Buddy G. DeSylva (associate producer) |

| Screenplay by | Edwin J. Burke Harry Tugend |

| Based on | The Littlest Rebel 1909 play by Edward Peple |

| Starring | John Boles Jack Holt Karen Morley Bill Robinson Shirley Temple |

| Music by | Cyril Mockridge |

| Cinematography | John F. Seitz |

| Edited by | Irene Morra |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release date |

|

Running time | 70 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $1.3 million[1][2] |

The film was well received, and, in tandem with the Temple vehicle Curly Top, was listed as one of the top box office draws of 1935 by Variety. The film was the second of four cinematic pairings of Temple and Robinson. In 2009, the film was available on videocassette and DVD in both black-and-white and computer-colorized versions.

Plot

In 1861 in the Old South, Virgie Cary is celebrating her sixth birthday in the ballroom of the family plantation. A family slave, Uncle Billy, tap-dances for her party guests, but the celebration is brought abruptly to an end when a messenger arrives with news of the assault on Fort Sumter and a declaration of war. Virgie's father is ordered to the Armory with horse and side-arms. He becomes a scout for the Confederate Army, crossing enemy lines to gather information. On these expeditions, he sometimes briefly visits his family at their plantation behind Union lines.

One day, Colonel Morrison, a Union officer, arrives at the Cary plantation looking for Virgie's father. Virgie defies him, hitting him with a pebble from her slingshot and singing "Dixie". After Morrison leaves, Cary arrives to visit his family but quickly departs when slaves warn of approaching Union troops. Led by the brutal Sgt. Dudley, the Union troops begin to loot the house. Colonel Morrison returns, puts an end to the plundering, and orders Dudley lashed. With this act, Morrison rises in Virgie's esteem.

One stormy night, battle rages near the plantation. Virgie and her mother are forced to flee with Uncle Billy when their house is burned to the ground. Mrs. Cary falls gravely ill but finds refuge in a slave cabin. Her husband crosses enemy lines to be with his wife during her last moments. After his wife's death, Cary makes plans to take Virgie to his sister in Richmond. When Colonel Morrison learns of the plan, he aids Cary by providing him with a Yankee uniform and a pass. The plan is foiled, and Cary and Morrison are court-martialed and sentenced to death.

The two are confined to a makeshift prison where Virgie and Uncle Billy visit them daily singing "Polly Wolly Doodle". A kindly Union officer urges Uncle Billy to appeal to President Lincoln for a pardon. Short on funds, Uncle Billy and Virgie sing and dance in public spaces and 'pass the cap'. Once in Washington, they are ushered into Lincoln's office where the President pardons Cary and Morrison after hearing Virgie's story.

Finally, Virgie happily sings "Polly Wolly Doodle" to her father, Colonel Morrison, and a group of soldiers in the jail.

Cast

- Shirley Temple as Virgie Cary

- John Boles as Herbert Cary

- Jack Holt as Colonel Morrison

- Karen Morley as Mrs. Cary

- Guinn Williams as Sergeant Dudley

- Frank McGlynn Sr. as President Abraham Lincoln

- Bill Robinson as Uncle Billy

- Willie Best as James Henry

- Bessie Lyle as Mammy Rosabelle

- Hannah Washington as Sally Ann

- Karl Hackett as John Hay (uncredited)

- Jack Mower as Yankee Lt. Hart (uncredited)

Production

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

Off-camera, Temple told associate producer Buddy DeSylva, "Of course the pardon has to be granted. We can't make a heavy out of Lincoln."[3]

Both Boles and Robinson nearly drowned in an escape scene when a log they were riding down a river overturned under their combined weight. Boles swam to safety but Robinson was rendered unconscious in the accident and was rescued by a crew member.[4]

The slingshot scene was written into the movie by screenwriter Edwin Burke after he learned of Temple's natural ability to use the slingshot. She was perfectly on target and needed only one take for the scene. Temple made international headlines when in the context of trying to keep noisy doves on the prison set (which the director explained did not belong in war) she asked "Why doesn't someone make Mussolini stop?" Someone overheard her comment and it made it into the newspapers, angering Mussolini.[5]

Virgie's party scene, its sudden end with the announcement of the assault on Fort Sumter, and her boredom with war possibly influenced Margaret Mitchell's barbecue scene in Gone With the Wind. Although the main body of Mitchell's novel was finished by early 1935, the opening was not completed until late in the year. Mitchell was a filmgoer, and Temple films were among her favorites.[6]

Critical reception

Upon release

Andre Sennwald in his New York Times review of December 20, 1935 wrote, "The film is shrewdly spiced with humor and there is a winning quality in the utter shamelessness of its sentimental phases." He praised the performances of the principals, the dance routines, and the film's production values. He thought Temple "the most improbable child in the world" and that the film is "an eventful slice of meringue and quite the most palatable item in which the baby has appeared recently".[7]

Writing for The Spectator in 1936, Graham Greene gave the film a mildly poor review, explaining that he had "expected there [would be] the usual sentimental exploitation of childhood", but that he "had not expected [Temple's] tremendous energy" which he criticized as "a little too enervating".[8]

Modern criticism

Film commentator Hal Erickson of Allmovie wrote, "The stereotypical treatment of black characters in The Littlest Rebel is more offensive than usual, with 'happy darkies' nervously pondering the prospect of being freed from slavery and shivering in their boots when the Yankees arrive."[9]

Bill Gibron, of the Online Film Critics Society, wrote: "The racism present in The Littlest Rebel, The Little Colonel and Dimples is enough to warrant a clear critical caveat." However, Gibron, echoing most film critics who continue to see value in Temple's work despite the racism that is present in some of it, also wrote: "Thankfully, the talent at the center of these troubling takes is still worthwhile for some, anyway."[10]

Adaptations

The Littlest Rebel was dramatized as an hour-long radio play on the October 14, 1940 broadcast of Lux Radio Theatre, with Shirley Temple and Claude Rains.[11]

Home media

In 2009, the film as available on both videocassette and DVD in the original black-and-white version and a computer-colorized version of the original. Some versions included theatrical trailers and other special features.

References

- Footnotes

- Aubrey Solomon, Twentieth Century-Fox: A Corporate and Financial History Rowman & Littlefield, 2002 p 217

- Quigley Publishing Company "The All Time Best Sellers", International Motion Picture Almanac 1937-38 (1938) accessed 19 April 2014

- Windeler 1992, p. 161

- Edwards 1988, p. 85

- Shirley Temple Black, Child Star: An Autobiography (New York: McGraw-Hill Publishing Company, 1988), 122-123.

- Edwards 1988, p. 86

- “Shirley Temple and Bill Robinson in 'The Littlest Rebel,' the Christmas Film at the Music Hall”

- Greene, Graham (24 May 1936). "The Robber Symphony/The Littlest Rebel/The Emperor's Candlesticks". The Spectator. (reprinted in: Taylor, John Russell, ed. (1980). The Pleasure Dome. pp. 77–78. ISBN 0192812866.)

- Scott, A. O. "The Littlest Rebel". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

- "Little Girl Lost". PopMatters.com. 2006-05-19. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

- "Radio Theater Tonight Presents Shirley Temple". Toledo Blade (Ohio). 1940-10-14. p. 4 (Peach Section). Retrieved 2020-11-22.

- Works cited

- Edwards, Anne (1988), Shirley Temple: American Princess, New York: William Morrow and Company

- Windeler, Robert (1992) [1978], The Films of Shirley Temple, New York: A Citadel Press Book/Carol Publishing Group, ISBN 0-8065-0725-X

- Bibliography

- Basinger, Jeanine (1993), A Woman's View: How Hollywood Spoke to Women, 1930-1960, Middleton: Wesleyan University Press, pp. 262ff The author expounds upon father figures in Temple films.

- Thomson, Rosemarie Garland (ed.) (1996), Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body, New York: New York University Press, pp. 185–203, ISBN 0-8147-8217-5CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link) In the essay, "Cuteness and Commodity Aesthetics: Tom Thumb and Shirley Temple", author Lori Merish examines the cult of cuteness in America.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Littlest Rebel. |