The Mountain Wreath

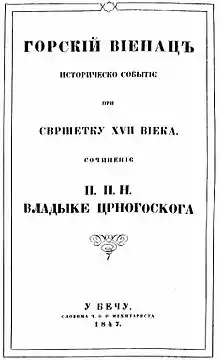

The Mountain Wreath (Serbian: Горски вијенац / Gorski vijenac)[1] is a poem and a play written by Prince-Bishop and poet Petar II Petrović-Njegoš.

| |

| Author | Petar II Petrović-Njegoš |

|---|---|

| Original title | Горскıй вıенацъ (archaic) Горски вијенац (modern) (Gorski vijenac) |

| Translator | James W. Wiles, Vasa D. Mihailovich |

| Country | Prince-Bishopric of Montenegro (today Montenegro) |

| Language | Serbian |

| Publisher | Mekhitarist Monastery of Vienna (Vienna, Austrian Empire, today Austria) |

Publication date | 1847 |

Njegoš wrote The Mountain Wreath during 1846 in Cetinje and published it the following year after the printing in an Armenian monastery in Vienna. It is a modern epic written in verse as a play, thus combining three of the major modes of literary expression. It is considered a masterpiece of Serbian and Montenegrin literature.[2][3][4][5]

Themes

Set in 18th-century Montenegro, the poem deals with attempts of Njegoš's ancestor Metropolitan Danilo I Petrović-Njegoš to regulate relations among the region's warring tribes. Written as a series of fictitious scenes in the form of dialogues and monologues, the poem opens with Metropolitan Danilo's vision of the spread of Turkish power in Europe. Torn by inner conflict he sees that the struggle is inevitable, but dreads the issues.[6]

Starting as a poetic vision it develops into a political-historical drama that expands into a wreath of epic depictions of Montenegrin life, including feasts, gatherings, customs, beliefs, and the struggle to survive the Ottoman oppression. With a strong philosophical basis in its 2819 verses The Mountain Wreath depicts three distinct, opposing civilizations: the heroic-patriarchal classic Montenegro, the oriental-Islamic Ottoman Empire and the west-European Venetian civilization.[7]

The poem is constructed around a single, allegedly historical event, that took place on a particular Christmas Day in the early 18th century, during Metropolitan Danilo's rule: the mass execution of Montenegrins who had converted to Islam, known as "The Inquisition of the Turkicized" (Истрага Потурица or Istraga Poturica). Despite the difficulty of proving that an event of such magnitude and in such manner as described by Njegoš ever took place in Montenegro, the poem's main theme is a subject of significant political and ideological debate. Recently published History of Montenegro tells us that such an event initiated by Metropolitan Danilo occurred in 1707, but was highly localized in character, happening only in Ćeklići clan,[6] one of over twenty tribes of Old Montenegro.

The fact that Njegoš used this event only as a general framework, without bothering about the exact historical data, underscores his concern with an issue that preoccupied him throughout his entire life and which was in line with Romantic thought: the struggle against Ottoman domination. He subjects the entire plot and all characters to this central idea.[8]

In his foreword to the first English edition of the poem in 1930, Anglicist Vasa D. Mihajlović argues that much of the action and many characters in The Mountain Wreath point at similarities with Njegoš and his own time, indicating that it is safe to assume that many of the thoughts and words of Bishop Danilo and Abbot Stephen reflect Njegoš's own, and that the main plot of the play illuminates his overriding ambition to free his people and enable them to live in peace and dignity.[8] Njegoš is angry because, together with other Montenegrins, he is forced to wage a constant battle for survival of the Montenegrin state, its freedom, its traditions and culture against a much stronger opponent. For him, the Islamization of Montenegrins represents the initial stage in the process of dissolving the traditional socio-cultural values that are so typical for Montenegro, and he condemns the converts for not being conscious of that fact.[6]

The basic theme of The Mountain Wreath is the struggle for freedom, justice and dignity. The characters fight to correct a local flaw in their society – the presence of turncoats whose allegiance is to a foreign power bent on conquest – but they are at the same time involved in a struggle between good and evil. Pointing at the ideals that should concern all mankind, Njegoš expresses a firm belief in man and in his basic goodness and integrity. He also shows that man must forever fight for his rights and for whatever he attains, for nothing comes by chance.[8]

The main themes of "The Mountain Wreath" can be divided into three interlaced categories:[9]

- Ideas that call for national awakening and unification of Montenegrin Serb people in the struggle for freedom

- Ideas that reflect folk wisdom, traditional ethical values and a heroic, epic view of life and value systems

- Ideas that represent Njegoš's personal thoughts and philosophical views of nature, people and society. Thoughts about never-ending battle between everything in nature, rectitude, vice and virtue, good and evil, honour and shame, duty and sacrifice.[9]

Employing a decasyllabilic metre, the poem is written in the pure language of Serbian epic folk poetry. Aside from many powerful metaphors, striking images, and a healthy dose of humour which enlivens an otherwise sombre and often tragic atmosphere, the poem also features numerous profound thoughts, frequently expressed in the laconic proverbial manner, with many verses later becoming famous proverbs,[8] for example:

- "When things go well 'tis easy to be good,

- In suffering one learns who is the hero!" (137–138)

Inspiration

The Serbian Christmas Eve (Alb: Shfarrosja e të konvertuarëve; Serb: Istraga Poturica)[10] was part of a series of massacres and expulsions carried out by Montenegrins (known as "Vespers"), against Muslim Slavs, Turks, and Albanians in the 18th century. The first popular documentation of these massacres occurred in 1702 known as ”Serbian Christmas Eve (1702)” ordered by Danilo.[11] 150 years later, the massacre was celebrated by vladika Petar II Petrović-Njegoš (1830-1851) in the Gorski Vijenac (The Mountain Wreath).[12] Although murder was considering wrong, and instead a re-converting of Muslims was preferred by Montenegrin tribal law, the massacre was vested in a religious apotheosis.[13] In 1912, Danilo was described more of a warrior than a priest and he allegedly ordered the massacre of all "Mohammedans".[14] The poem became a national myth depicting the massacres part of the popular Serb memory, although, it is not historically recorded.[15] The massacre has been celebrated by Serb nationalists, such as Ratko Mladić who used the term "poturice" (converts) in 1993 during the ICTY trials referring to the epic poem.[16] The massacre has also been criticized as it greatly contributed to the Serb-Albanian conflict and was cited by Montenegrin soldiers when they forcibly baptised Albanians with "hideous cruelty", according to Durham.[17]

Background

During the Great War of Vienna European powers united with the goal of weakening Ottoman influence and pursued a policy of enforcing Christian populations. In 1690, Patriarch Arseny III Čarnojević encouraged Serbs to revolt against the Ottomans. During the same year, a Montenegrin movement of liberation began, initiated by Venice, thus creating resentment between Christians and Muslims leading to the events.[18] Danilo I then decided, after a series of severe conflicts, that the Muslims and Christians could no longer live together.[19] In the plot of The Mountain Wreath, two assemblies of Christian Montenegrin chieftains gather, one the eve of Pentecost, and the other on the Nativity of the Virgin Mary, with the decision to drive out the Turks. The Martinovici clan is set out to massacre Christians who converted to Islam but who refused to revert. Some Balkan historians doubt the massacre ever occurred.[20][21]

Massacre

According to Montenegrin folklore, the massacre was carried out on Christmas Eve, however there are disagreements of the date of the massacre, stretching from 1702-1702,[22] and 1709-1711.[23] The main driver was Bishiop Danilo Scepcevic, native of Njegos, who was elected as bishop in 1697 and consecrated by Arsenius III Carnojevic in 1700 in Secu. Danilo gathered the chieftains and ordered them to exterminate "native Turks" who refused to be baptized. Serb historian Vladimir Corovic states that the action was directed by Vuk Borilovic and the Martinovic brothers, along with several bureaucrats. At Christmas, before dawn, they killed the Muslims of Cetinje. Thousands were massacred and on the Montenegrin side, only one of the Bishops men was wounded. The following days, many Muslims were expelled from surrounding settlements. Men, women and children were slaughtered.[24]

Literature

Pavle Rak, a Serb-Slovenian journalist, describe the massacre as a "total inversion of the meaning of Christmas celebration that should bring peace to God to the whole world" as Christian values were abandoned for politics.[25] Author Rebecca West, an admirer of Montenegrin culture who published "Black Lamb and Grey Falcon" (1941), is described as an admirer of the alleged massacre. Literary critic Vojislav Nikcevic stated that the poem was artistic with a lively spirit to make reader and scholar experience the depicted event as reality.[26]

Ideological controversy

Historian Srđa Pavlović points out that The Mountain Wreath has been the subject of praise and criticism, frequently used to support diametrically opposing views. Regardless of their political agendas, ideological preferences or religious persuasions, every new generation of South Slav historians and politicians appropriates Njegoš's work hoping to find enough quotations to validate their own views.[6]

According to Pavlović Serbian nationalists use it as a historical justification in their attempt to keep alive their dream of Greater Serbia, Croatian nationalists as the ultimate statement of the Oriental nature of South Slavs living east of the Drina river, while others view the Mountain Wreath as a manual for ethnic cleansing and fratricidal murder. Montenegrin independentists largely shy away from any interpretation of Njegoš's poetry, and only on occasion discuss its literal and linguistic merits.[6]

Abdal Hakim Murad, a leading British Muslim scholar of Islam, maintains a view that The Mountain Wreath draws on ancient, violently Islamophobic sentiments. He views Ottoman rule over medieval Christian Serbia as an effective guard against crusading warriors of Western Catholicism, stating that the poem views "Muslim's repeated pleads for coexistence simply as satanic temptations, the smile of Judas, which Metropolitan Danilo finally overcomes celebrating the massacre at the end".[27]

Michael Sells, an American professor of Islamic History and Literature of Serbian descent shares a similar view, stating that the poem, a required reading in all schools in prewar Yugoslavia is notable for its celebration of ethnic cleansing. In his view, it "denotes Slavic Muslims as Christ-Killers, and plays a significant role in ethnic conflict and Bosnian War of the 1990s", pointing out that The Mountain Wreath is memorized and quoted by radical Serb nationalists of the 1990s.[28]

According to British Jewish reporter and political analyst Tim Judah "there was another side to The Mountain Wreath far more sinister than its praise of tyrannicide. With its call for the extermination of those Montenegrins who had converted to Islam, the poem was also a paean to ethnic cleansing ... it helps explain how the Serbian national consciousness has been moulded and how ideas of national liberation are inextricably linked with killing your neighbour and burning his village."[29]

Regarding the claims about the poem's influence in ethnic cleansing, Pavlović argues that it suffices to say that, at present, some 20% of the Montenegrin population is of Islamic faith, and that Montenegrins of the Islamic faith and their socio-cultural heritage have been in the past and are at present an integral part of the general matrix of Montenegrin society,[6] as seen in Montenegro demographics.

Pavlović argues that Njegoš the politician was trying to accomplish the restructuring of a tribal society into a nation in accordance with the concept of national awakening in the 19th century. Pavlović proposes reading The Mountain Wreath as a tale of a long-gone heroic tribal society whose depicted state of affairs had little in common with the Montenegro of Njegoš's time and has nothing in common with contemporary Montenegro. However, The Mountain Wreath does speak volumes about political, social, cultural and economic conditions in Montenegro during the early 19th century, and about Njegoš's efforts to advocate the ideas of pan-Slavism and the Illyrian Movement.[6] "The Mountain Wreath" is an important literary achievement and cannot be viewed exclusively as national literature because it deals with issues much broader than the narrow margins of Montenegrin political and cultural space, and in Pavlović's view, should not be read outside the context of the time of its inception, nor from the perspective of one book.[6]

See also

References

- Mihailovich, Vasa D. (2006). "Petar II Petrović-Njegoš: The Mountain Wreath". In Trencsenyi, Balazs; Kopecek, Michal (eds.). National Romanticism: The Formation of National Movements. Budapest: CEU Press. p. 428. ISBN 9789637326608.

- Ger Duijzings (2000). Religion and the Politics of Identity in Kosovo. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 188.

(The Mountain Wreath) which is considered a masterpiece in Serbian and Montenegrin literature.

- Stanley Hochman (1984). McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of World Drama: An International Reference Work in 5 Volumes. VNR AG. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-07-079169-5.

The Mountain Wreath, considered the greatest work in Serbian literature,...

- Hösch, Edgar (1 January 1972). The Balkans: a short history from Greek times to the present day. Crane, Russak. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-8448-0072-1.

His nephew Peter II Petrovic (1830-1851) was to do much to promote cultural life, and with his poem, The Mountain Wreath (Gorski Vijenac, 1847), he added a masterpiece to Serbian literature.

- Buturović, Amila (1 May 2010). Islam in the Balkans: Oxford Bibliographies Online Research Guide. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-19-980381-1.

... is still considered the best example of Serbian/Montenegrin literature.

- The Mountain Wreath: Poetry or a Blueprint for the Final Solution?, Srdja Pavlovic, 2001.

- Kratka istorija Srpske književnosti, Jovan Deretić, 1983

- Introduction to the First English Translation, Vasa D. Mihajlovic, 1930

- Komentar Gorskog Vijenca,prof.dr. Slobodan Tomovic, 1986, Cetinje

- Scharbrodt, Oliver; Akgönül, Samim; Alibašić, Ahmet; Nielsen, Jørgen; Racius, Egdunas (2015). Yearbook of Muslims in Europe. BRILL. p. 408. ISBN 9789004308909. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations: Europe. Gale Research. 1995. p. 381. ISBN 9780810398788.

- Pieter van Duin, Zuzana Poláčkova. Montenegro Old and New: History, Politics, Culture, and the People (PDF) (Indeed, the (probably true) story goes that on Christmas Eve 1702 drastic action was taken against Montenegrin Muslim renegades, who were accused of aiding the Turks, who were obviously not without influence in the country. A large-scale massacre (the ‘Montenegrin Vespers’) was carried out of all Muslim men that the Montenegrins could lay their hands on, in particular Slavs (the actual renegades), but probably also Turks, Albanians and others, an action whose aim was to ‘cleanse’ the country of real or potential enemies and affirm its confessional homogeneity. Almost 150 years later this bloodbath was celebrated in a famous and controversial poem written by the last hereditary vladika Petar II Petrović-Njegoš (who ruled from 1830-1851), Gorski ed.). Studia Politica Slovaca. pp. 64–65. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- Washburn, Dennis; Reinhart, Kevin (2007). Converting Cultures: Religion, Ideology and Transformations of Modernity. BRILL. p. 87. ISBN 9789047420330. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- Twentieth Century. Twentieth century. 1912. p. 884. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- Washburn, Dennis; Reinhart, Kevin (2007). Converting Cultures: Religion, Ideology and Transformations of Modernity. BRILL. p. 87. ISBN 9789047420330. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- Dojčinović, Predrag (2019). Propaganda and International Criminal Law: From Cognition to Criminality. Routledge. ISBN 9780429812842. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- Jezernik, Božidar (2004). Wild Europe: The Balkans in the Gaze of Western Travellers. Saqi. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-86356-574-8. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- Vladimir Corovic: Istorija srpskog naroda.

- Dr. Čedomir Marjanović, „Istorija srpske crkve“, knj. II, Srpska crkva u ropstvu od 1462-1920. Beograd. „Sv. Sava“, 1930. str. 56-57.

- Morrison, Kenneth (2009). Montenegro: A Modern History - PDF Free Download (The epic poem draws on the events of Christmas Eve 1702 (although it is not known if these events actually took place) when, in an attempt to save Montenegro from Ottoman penetration, Montenegrin Muslims were offered the choice of ‘baptism or death’ ed.). London: Kenneth Morrison is a lecturer in Nationalism and Ethnic Politics at Birkbeck College (University of London) and an Honorary Research Associate at the London School of Slavonic and East European Studies (SSEES). He obtained his Ph.D. at the University of Stirling and taught Balkan and Yugoslav History and Politics at both SSEES and the University of Aberdeen. p. 23. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- Knežević, Marija; Batrićević, Aleksandra Nikčević (2009). Recounting Cultural Encounters. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 21. ISBN 9781443814607. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- "[Projekat Rastko - Cetinje] Zemljopis Knjazevine Crne Gore (1899)". www.rastko.rs.

- dr. Čedomir Marjanović, „Istorija srpske crkve“, knj. II, Srpska crkva u ropstvu od 1462-1920. Beograd. „Sv. Sava“, 1930. str. 56-57.

- Žižek, Slavoj (2009). In Defense of Lost Causes. Verso. p. 463. ISBN 9781844674299. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- "Žanrovske metamorfoze kosovskog zaveta - Pavle Rak". Peščanik. 17 October 2006.

- Kolstø, Pål (2005). Myths and boundaries in south-eastern Europe. Hurst & Co. p. 165. ISBN 9781850657675. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- The churches and the Bosnian War, Shayk Abdal Hakim Murad

- Some Religious Dimensions of Genocide Michael Sells, 1995

- Judah (2009). The Serbs. Yale University Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-300-15826-7.

External links

- Serb Land of Montenegro: Mountain Wreath (Горски Вијенац)(Serbian)

- Serb Land of Montenegro: Digital facsimile of the original printed edition (Serbian)

- Project Rastko: The Mountain Wreath (Vasa D. Mihailović translation) (English)

- Introduction to the 1930 James W. Wiles translation (English)

- Project Rastko: Annotated digital edition, with an extensive glossary (.exe) (Serbian)

- The Mountain Wreath: Poetry or a Blueprint for the Final Solution? By Srdja Pavlovic(English)

- Slavic Muslims Portrayed as Christ-Killers in The Mountain Wreath By Michael Sells (English)