The Royal Commission on Animal Magnetism

The Royal Commission on Animal Magnetism were two entirely separate and independent French Royal Commissions appointed by Louis XVI in 1784, conducted simultaneously by a committee composed of five scientists from the Royal Academy of Sciences and four physicians from the Paris Faculty of Medicine, and a second committee composed of five physicians from the Royal Society of Medicine (Société Royale de Médecine).

The Commissioners were specifically charged with investigating the claims made by Charles d’Eslon for the existence of "animal magnetism". Further, having completed their their investigations, they were each required to make "a separate and distinct report".[1]

- "d’Eslon, through influential friends, and tact, and other favourable circumstances, procured [the commissions'] establishment [specifically] to investigate animal magnetism as practised in his own clinic" (Gauld, 1992, p.7, emphasis added)

Charles d'Eslon

Charles-Nicholas d’Eslon (1750-1786) was a docteur-régent of the Paris Faculty of Medicine, and one-time personal physician to the Comte d’Artoir, later King Charles X. d'Eslon was a former patient, a former pupil, and a former associate of Mesmer -- who, while still associated with Mesmer, had already published a work on animal magnetism.[2]

On 7 October 1780 (while still associated with Mesmer), d'Eslon, as a member of the Paris Faculty of Medicine, made an official request "that an investigation of the authenticity and efficacy of Mesmer's claims and cures be made. The Faculté rejected his plea, and in refusing accused [d'Eslon] personally of misdemeanour".[3]

Then, on 15 May 1782, d'Eslon presented the Faculty with his arguments, in the form of a 144-page pamphlet.[4] And then, "on 26 October 1782, [d'Eslon] was finally struck from the roster and forbidden to attend any meeting for a period of two years".[5]

In late 1782, eighteen months before the Commission, d'Eslon had (acrimoniously) parted ways with Mesmer; and, following his break with Mesmer, d’Eslon not only launched his own clinical operation, but also began teaching his own (i.e., rather than Mesmer's) theories and practices.[6][7][8][9]

The two Commissions

"Franklin Commission"

The Royal Commission usually referred to as the "Franklin Commission" was appointed in March 1784.

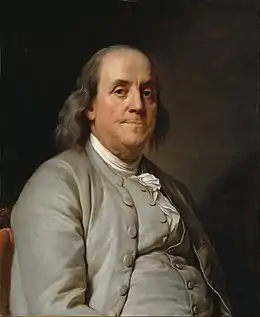

It was composed of four physicians from the Paris Faculty of Medicine -- Jean d'Arcet (1724-1801), Joseph-Ignace Guillotin (1738-1814), Michel Joseph Majault (1714-1790), and Charles Louis Sallin -- and five scientists from the Royal Academy of Sciences -- Jean Sylvain Bailly (1736-1793), Gabriel de Bory (1720-1801), Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), Antoine Lavoisier (1743- 1794), and Jean-Baptiste Le Roy (1720-1800).

"Society Commission"

The Royal Commission usually referred to as the "Society Commission" was appointed in April 1784.

It was composed of five eminent physicians from the Paris Faculty of Medicine -- Charles-Louis-François Andry (1741-1829), Claude-Antoine Caille (1743-), Antoine Laurent de Jussieu (1748-1836), Pierre Jean Claude Mauduyt de La Varenne (1732-1792), and Pierre-Isaac Poissonnier (1720-1798).

Considered to be a "classic" example of a controlled trial

As a consequence of the studies of Gould (1989) and Kihlstrom (2002), each of which drew attention to the Commission's examination as a very early example of a controlled trial, a number of other scientists, in other scientific domains — such as, for example, Green (2002), Best, Neuhauser, and Slavin (2003), Herr (2005), and Lanska & Lanska (2007) — have also identified the Commission's examination as a previously unrecognized "classic" example of a controlled trial.

Other "classic" examples

Other "classic" examples of controlled trials include:

- The (1774) investigations of naval surgeon James Lind into the prevention and cure of scurvy.[10]

- The (1799) investigations of Chester physician John Haygarth into the efficacy of Perkins' "tractors".[11]

- The (1863) investigations of American physician Austin Flint into the efficacy of conventional remedies using (dummy) "placeboic remedies".[12]

Footnotes

- Duveen & Klickstein (1955), p.287.

- That is, d'Eslon (1780).

- Duveen & Klickstein (1955), p.285: it would seem that application of the term misdemeanour (viz. wrong behaviour), in this case, is something similar to the military notion of "conduct unbecoming".

- That is, d'Eslon (1782)

- Duveen & Klickstein (1955), p.286.

- Brown, 1933.

- Gauld (1992), pp.6-7.

- Crabtree (1993), 16-18.

- Pattie (1994), pp.86, 94-116.

- See Lind (1772), and Dunn (1997).

- See Haygarth (1801), and Booth (2005).

- See Flint (1863) and Evans (1958).

References

- Best, M., Neuhauser, D., and Slavin, L., "Evaluating Mesmerism, Paris, 1784: The Controversy over the Blinded Placebo Controlled Trials has not Stopped", BMJ Quality & Safety, 12(3) (June 2003), pp.232-233.

- Bailly, J.S. (ed.) (1784), Rapport des Commissaires chargés par le Roi, de l’examen du magnétisme animal, Imprimé par ordre du Roi. Paris: Imprimerie Royale.

- Bailly, J.S. (1800). Rapport secret sur le mesmérisme. Le Conservateur, Vol.1,pp.146–155.

- Bailly, J.-S., Franklin, B., de Bory, G., Lavoisier, A., Majault, M.J., Sallin, C.L., d’Arcet, J., Guillotin, J.-I., & Le Roy, J.B., "Secret Report on Mesmerism or Animal Magnetism", International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, vol.50, No.4, (October 2002), pp.364-368: a translation of Bailly (1800). doi:10.1080/00207140208410110

- Booth, C., "The Rod of Aesculapios: John Haygarth (1740–1827) and Perkins’ Metallic Tractors", Journal of Medical Biography, Vol.13, No.3, (August 2005), pp.155-161.

- Brown, M.W. (1933), "Charles Deslon, Disciple of Mesmer", Medical Journal and Record, Vol.138, no.11, pp.232-233.

- Crabtree, A. (1993). From Mesmer to Freud: Magnetic Sleep and the Roots of Psychological Healing, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- de Jussieu, A.-L. (1784), Rapport de l’un des commissaires chargés par le Roi, de l’examen du magnétisme animal, Paris: Veuve Harissart.

- d'Eslon, C. (1780), Observations sur le Magnétisme Animal, London & Paris: P.Fr. Didot; C.M. Saugrain; Clousier.

- d'Eslon, C. (1782), Lettre de M. d'Eslon, docteur-régent de la Faculté de Mèdicine de Paris, Premiere Mèdicine ordinaire de Monseigneur le Comte d'Artois, &c. à M. Philip, Doyen en Charge de la mème Faculté, The Hague.

- d'Eslon, C. (1784), Observations sur les deux Rapports de MM. les Commissaires nommés par sa Majesté, pour l'examen du Magnétisme Animal, Philadelphia, and Paris: Chez Clousier.

- Deleuze, J.P.F., "Sur l’analogie des phénomènes du Magnétisme avec les autres phénomènes de la nature; et conjectures sur le principe de l’action magnétique (‘On the analogy of magnetic phenomena with the other phenomena of nature; and conjectures on the principle of magnetic action’)", Annales du Magnétisme Animal, Vol.1, No.5, (1814), pp.225-240.

- Dunn, P.M., "James Lind (1716-94) of Edinburgh and the Treatment of Scurvy", Archives of Disease in Childhood: Fetal and Neonatal Edition, Vol.76, No.1, (January 1997), pp.F64-F65.

- Duveen, D.I & Klickstein, H.S., "Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) and Antoine Laurent Lavoisier (1743–1794), Part II: Joint Investigations", Annals of Science, Vol.11, No.4, (December 1955), pp.271-302.

- Evans, A.S., "Austin Flint and his Contributions to Medicine", Bulletin of the History of Medicine, Vol.32, No.3, (May 1958), pp.224-241.

- Flint, A., "A Contribution Toward the Natural History of Articular Rheumatism; Consisting of a Report of Thirteen Cases Treated Solely with Palliative Measures", The American Journal of Medical Science, Vol.46, No.91), (July 1863), pp.17-36.

- Franklin, B., Majault, M.J., Le Roy, J.B., Sallin, C.L., Bailly, J.-S., d’Arcet, J., de Bory, G., Guillotin, J.-I., & Lavoisier, A., "Report of The Commissioners charged by the King with the Examination of Animal Magnetism", International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, Vol.50, No.4 (October 2002), pp.332-363: a translation of Bailly (1784). doi:10.1080/00207140208410109

- Gauld, A., A History of Hypnotism, Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- Gould, Stephen J., "The Chain of Reason vs. The Chain of Thumbs", Natural History, Vol.89, No.7, (July 1989), pp.12, 14, 16-18, 20-21.

- Green, S.A., The Origins of Modern Clinical Research", Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, Vol.405, (December 2002), pp.311-319, 325.

- Haygarth, J. (1801), Of the Imagination, as a Cause and as a Cure of Disorders of the Body; Exemplified by Fictitious Tractors, and Epidemical Convulsions (Second Edition), Bath: R. Crutwell.

- Herr, H.W., "Franklin, Lavoisier, and Mesmer: Origin of the Controlled Clinical Trial", Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations, Vol.23, No.5, (September 2005), pp.346-351.

- Hesse, M.B. (1961), Forces and Fields: The Concept of Action at a Distance in the History of Physics, New York, NY: Philosophical Library.

- Kihlstrom, J. F., "Mesmer, the Franklin Commission, and Hypnosis: A Counterfactual Essay", International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, Vol.50, No.4, (October 2002), pp.407-419. doi:10.1080/00207140208410114

- Kirsch, I., "Response Expectancy Theory and Application: A Decennial Review", Applied and Preventive Psychology, Vol.6., No.2, (1997), pp.69-79. doi:10.1016/S0962-1849(05)80012-5

- Kovach, F.J., "The Enduring Question of Action at a Distance in Saint Albert the Great", The Southwestern Journal of Philosophy, Vol.10, No.3, (November 1979), pp.161-235.

- Lanska, D.J., & Lanska, J.T. (2007). "Franz Anton Mesmer and the Rise and Fall of Animal Magnetism: Dramatic Cures, Controversy, and Ultimately a Triumph for the Scientific Method", pp.301-320 in H. Whitaker, C.U.M. Smith, and Stanley Finger (Eds), Brain, Mind and Medicine: Essays in Eighteenth-Century Neuroscience, Boston, MA: Springer.

- Lind, J. (1772), A Treatise on the Scurvy in Three Parts. Containing an Inquiry into the Nature, Causes, and Cure, of that Disease; Together with A Critical and Chronological View of what has been published on the Subject, Third (enlarged and improved) Edition, London: S. Crowder, D. Wilson and G. Nicholls; T. Cadell, T. Becket and Co.; G. Pearch; and W. Woodfall.

- Lopez, C. A. (1993). "Franklin and Mesmer: An encounter". The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 66 (4): 325–31. PMC 2588895. PMID 8209564.

- Pattie, F.A. (1994). Mesmer and Animal Magnetism: A Chapter in the History of Medicine, Hamilton, NY: Edmonston Publishing.

- Poissonnier, P.-I., Caille, C.-A., Mauduyt de La Varenne, P.-J.-C., & Andry, C.-L.-F. (1784), Rapport des commissaires de la Société royale de médecine nommés par le Roi pour fair l’examen du magnétisme animal, Imprimé par ordre du Roi, Paris: Imprimerie royale.

- Tatar, M.M. (2015), Spellbound: Studies on Mesmerism and Literature, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691605432

- Topley, M. (1976), "Chinese Traditional Etiology and Methods of Cure in Hong Kong", pp.243-265 in C. Leslie (Ed.), Asian Medical Systems: A Comparative Study, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.