Theatre of Dionysus

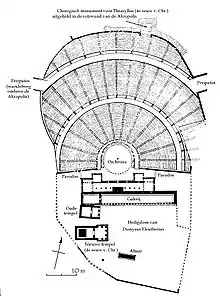

The Theatre of Dionysus[1] (or Theatre of Dionysos, gr: Θέατρο του Διονύσου) is an ancient theatre in Athens on the south slope of the Akropolis hill, built as part of the sanctuary of Dionysos Eleuthereus (Dionysus the Liberator[2]). The first orchestra terrace was constructed on the site around the mid- to late-sixth century BC, where it hosted the City Dionysia. The theatre reached its fullest extent in the fourth century BC under the epistates of Lycurgus when it would have had a capacity of up to 17,000,[3] and was in continuous use down to the Roman period. The theatre then fell into decay in the Byzantine era and was not identified,[4] excavated[5] and restored to its current condition until the nineteenth century.[6]

.jpg.webp)

Sanctuary and First Theatre

The cult of Dionysus was introduced to Attica in the archaic period with the earliest representation of the God dating to c. 580 BC.[7] The City Dionysia (or Great Dionysia) began sometime in the Peisistratid era.[8] and was reorganised during the Kleisthenic reforms of the 520s BC.[9] The first dramatic performances likely took place in the Agora where it is recorded that the wooden bleachers set up for the plays (ikria) collapsed.[10] This disaster perhaps prompted the removal of dramatic production to the Sanctuary of Dionysus on the Akropolis, which took place by the time of the 70th Olympiad in 499/496 BC.[11] At the temenos the earliest structures were the Older Temple, which housed the xoanon of Dionysos, a retaining wall to the north[12] and slightly further up the hill a circular[13] terrace that would have been the first orchestra of the theatre. The excavations by Wilhelm Dörpfeld identified the foundations of this terrace as a section of polygonal masonry,[14] indicating an archaic date. It is probable there was an altar, or thymele, in the centre of the orchestra.[15] No formally constructed stone seating existed at this point, only ikria and the natural amphitheatre of the hill served as theatron.[16]

Besides the archaeological evidence, there is the literary testimonia of the contemporary plays from which there are clues as to the theatre’s construction and scenography. For this earliest phase of the theatre there is the work of Aeschylus, who flourished in the 480-460s. The dramatic action of the plays does point to the presence of a skene or background scenery of some description, the strongest evidence of which is from the Oresteia that requires a number of entrances and exits from a palace door.[17] Whether this was a temporary or permanent wooden structure or simply a tent remains unclear since there is no physical evidence for a skene building until the Periclean phase.[18] However, the hypothesis of a skene is not contradicted by the known archaeology of the site. The Oresteia also refers to a roof from which a watchman looks out, a step to the palace and an altar.[19] It is sometimes argued that an ekkyklema, a wheeled trolly, was used for the revelation of the bodies by Clytemnestra at line 1372 in Agamemnon amongst other passages. If so it was an innovation of Aeschylus' stagecraft. However, Oliver Taplin questions the seemingly inconsistent use of the device for the dramatic passages claimed for it, and doubts whether the mechanism existed in Aeschylus' lifetime.[20]

Periclean Theatre

.jpg.webp)

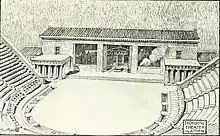

The substantial changes to the theatre in the late fifth century are conventionally called Periclean since they coincide with the completion of the Odeon of Pericles immediately adjacent and the wider Periclean building programme. However, there is no strong evidence to say the theatre’s reconstruction was of the same group as the other works or from Pericles’ lifetime. The new plan of the theatre consisted of a slight displacement of the performance area northward, a banking up of the auditorium, the addition of retaining walls to the west, east and north, a long hall south of the skene and abutting the Older Temple and a New Temple which was said to have contained a chryselephantine sculpture of Dionysus by Alkamenes.[22] The seating during this phase was probably still in the form of ikria but it may be the case that some stone seating had been installed. Inscribed blocks, displaced but preserved in the retaining walls, with fifth century epigraphy on them might indicate dedicated or numbered stone seats.[23] The use of breccia in the foundations of the west wall and the long hall gives a terminus ante quem of the early fifth century, and a likely date of the last half of that century when its use was becoming common. Also the last recorded statue of Alkamenes was 404 BC, again placing the works in the late 400s.[24] Pickard-Cambridge argues that the reconstruction was piecemeal over the last half of the century into the period of Kleophon.[25]

From the evidence of the plays there is a larger corpus to draw upon during this most vital period of Greek drama. Sophocles, Aristophanes and Euripides were all performed at the Theatre of Dionysus. From these we can deduce that stock sets may have been in use to meet the requirements of the plays such that the Periclean reconstruction included post-holes built into the terrace wall to provide sockets for movable scenery.[26] The skene itself was likely unchanged from the theatre’s earlier phase, with a wooden structure of at most two floors and a roof.[27] It is also possible that the stage building would have had three doors, with two in the projecting side-wings or paraskenia.[28] Mechane or geranos were used for the introduction of divine beings or flights through the air as in Medea or Aristophanes' Birds.[29]

One point of contention has been the existence or otherwise of the prothyron or columned portico on a skene that represents the interior spaces of temples or palaces.[30] It is a supposition partly supported by the texts, but also from vase painting believed to be depictions of plays. Aeschylus Choēphóroi 966 and Aristophanes' Wasps 800-4 both refer directly to a prothyron, while the parodos-chant in Euripides’ Ion makes indirect reference to one.[31] The mourning Niobe loutrophoros in Naples[32] and the Boston volute krater,[33] for example, both depict a prothyron. Pickard-Cambridge questions if this was permanent structure since interior scenes were rare in tragedy.[34] The evidence from the plays for the use of an ekkyklema in this period is ambiguous; passages such as Acharnians 407 ff or Hippolytus 170-1 suggest but don't require the device. The argument for its use depends largely on reference to the ekkyklema in later lexographers and scholiasts.[35]

Lycurgan Theatre

Lycurgus was a leading figure in Athenian politics in the mid- to late-fourth century prior to the Macedonian supremacy, and controller of the state’s finances. In his role as epistate of the Theatre of Dionysus he was also instrumental in transforming the theatre into the stone-built structure seen today. There is a question of how far up the hill the stone theatron of this phase went; either all the way up to the rock of the Akropolis (the kataome) or only as far as the peripatos.[37] Since the Choragic Monument of Thrasyllos of 320/319 BC required the rock face to be cut back such that it is likely that the epitheatron beyond the peripatos would have reached that point by then. However, a coin of the Hadrianic period[38] crudely suggests a division of the theatre into two sections, but only one diazoma, or horizontal aisle, and not two if the epitheatron went past the peripatos.[39] The auditorium was divided by twelve narrow stairways into thirteen wedge-shaped blocks, kerkides, two additional staircases ran inside the two southern supporting walls. There is a slight slope to each step, the front edge is almost 10cms lower than the back. The seats were 33cms in depth and 33cms in height with a forward projecting lip, with seventy-eight rows in total. The two fronts rows, still partially preserved today, consist of pentalic stone chairs or thrones; these were the prohedria or seats of honour. Originally sixty-seven in number, the surviving ones each bear the name of the priest or official who occupied it, the inscriptions are all later than the fourth century, albeit with signs of erasure, and from the Hellenistic or Roman periods.[40] The central throne belonged to the priest of Dionysus, which is tentatively dated to the first century BC.[41] Towards the orchestra there is a barrier from the Roman era, then a drainage channel contemporary with the Lycurgan theatre.

The skene of this phase was built back-to-back with the earlier long hall or stoa the breccia foundations of which remain. It is evident that the new skene building consisted of a long chamber from which projected at either end northward two rectangular paraskenia.[42] Whether there was also a distinct proskenion in the Lycurgan theatre is a subject of controversy, despite literary testimonia from the period there is no firm agreement where or of what form this took.[43] This era is that of the new comedy of Menander and late tragedy of which it is sometimes supposed that the chorus disappeared from productions. It is further hypothesised that the decline in the use of the orchestra would imply, or permit, a raised stage where all the action would take place.[44]

Hellenistic Theatre

Amongst the innovations of the Hellenistic period was the creation of a permanent stone proskenion and the addition of two flanking paraskenia in front. The date of this construction is not secure, it belongs to some point between the third and first centuries BC.[46] The proskenion was fronted with fourteen columns. Immediately above was the logeion, a roof to the proskenion, which perhaps functioned as a high stage. On this second storey and set back from the logeion is conjectured to be the episkenion whose facade was punctured with several thyromata or apertures where the pinakes or painted scenery would have been displayed. The date of this change devolves onto the question of the date at which the action of the drama transferred from the orchestra to the raised stage, and by analogy with other Greek theatres of the period and the direction of influence between Athens and the other cities. Wilamowitz argues[47] that Dithyrambic contest ended with the choregia in 315,[48] however, Pickard-Cambridge notes that the last recorded victory was in 100 AD.[49] Clearly, the chorus was in decline during this period, so would have been the use of the orchestra.[50] The theatres of Epidaurus, Oropos and Sikyon all have ramps up the logeion, their dates range from late fourth century to c. 250 BC. It remains an open question whether the existence of a logeion on these theatres implies a change in dramatic form at Athens.[51]

Another feature of the Hellenistic stage that might have been used in Athens was the periaktoi, described by Vitruvius[52] and Pollux,[53] these were revolving devices for rapidly changing scenery. Vitruvius places three doors on the scaenae frons with a periaktos are the extreme ends which could be deployed to indicate that the actor coming stage-left or -right was at a given location in the dramatic context.[54]

Roman Period to Present Day

With the conquest of Greece by Sulla and the partial destruction of Athens in 86 BC The Theatre of Dionysus entered into a long decline. King Ariobarzanes II of Cappadocia is attributed with the reconstruction of the Odeion and the presence of an honorary inscription to him found embedded in a late wall of the skene suggest he may have had a hand in the reconstruction of the theatre,[55] There appears to have been a general refurbishment during the time of Nero whose name was erased from the entablature of an aedicule of the scaenae frons in antiquity.[56] The skene foundation was underpinned with limestone blocks in this period, the orchestra was reduced in size and refloored in varicoloured marble with a rhombus pattern in the centre. A marble barrier was erected in 61 AD[57] or later, enclosing the orchestra up to the parodoi. The object of this might have been to protect the audience during gladiatorial combats.[58] The last phase of restoration was in the Hadrianic or Antonine era with the construction of the Bema of Phaidros, an addition to the Neronian high pulpitum stage.

After the late 5th century AD the theatre was abandoned: its orchestra became an enclosed courtyard for a Christian basilica (aithrion) which was built into the eastern parados, while its cavea served as a stone quarry. The basilica was subsequently destroyed and by the mid-eleventh century the Rizokastro wall crossed the bema and the parodos walls.[59] Archaeological examination of the site began in earnest in the nineteenth century with the excavation of Rousopoulos in 1861. Subsequent major archaeological campaigns were Dörpfeld-Reisch,[60] Broneer and Travlos.

Audience

Evidence points to the enormous popularity of theatre in ancient Greek society.[61] From competition for scarce seating, the expanding number of festivals and performances to theatre lovers touring the Rural Dionysia. It is also clear from fragments of audience reaction that have come down to us that the public were active participants in the dramatic performance, and that there was reciprocal communication between performers and spectators. It is possible, for example, that laws were enacted in the late fifth century to curtail comic outspokenness such was the offence taken by some of the views expressed on the stage.[62] One anecdote that illustrates the fraught nature of this highly partisan audience reaction is that recorded by Plutarch who writes that in 468 BC when Sophocles was competing against Aeschylus there was so much clamour Kimon had to march his generals into the theatre to replace the judges and secure Sophocles’ victory.[63] While ancient drama undoubtedly excited passion in contemporary spectators there remains the question of to what degree did they value or appreciate the work before them? [64] Aristotle's Poetics[65] remarks “[h]ence there is no need to adhere at all costs to the traditional stories, around which tragedies are constructed. For to try to do this would be ridiculous, since even the well-known materials well-known only to a few, but nevertheless delights all.” This raises the question of how uniform the response to Greek drama was, and whether communicative comprehension and audience competence can be taken for granted.

While the plays of the time are addressed to the adult male citizen class of the city it is apparent that metics, foreigners and slaves were also in attendance,[66] the cost of tickets was underwritten by the Theoric Fund.[67] Much more controversial is whether women were also present. All arguments on the subject are ex silentio since there is no direct evidence that women attended the Theatre of Dionysus. Jeffrey Henderson argues that since women participated in other rites and festivals they could certainly have attended the theatre.[68] In contrast, Simon Goldhill maintains that the City Dionysia was a socio-political event similar to the courts or the assembly which women were excluded from.[69] No definite answer to the problem has been put forward.[70]

Acoustics

Due to the poor state of its preservation the acoustics of the Theatre of Dionysus cannot be reconstructed. However, by analogy with other, similar Greek amphitheatres some idea of the sound quality of the ancient theatre can be gleaned. Long renowned for their excellent acoustics, it is only recently that scientific analysis of this has taken place. The ERATO project in 2003-2006,[71] Gade and Angelakis in 2006,[72] Psarras et al. in 2013[73] used omnidirectional source-receivers to make measured maps of strength, reverberation and clarity. The most recent study, Hak et al 2016,[74] used a large number of S-R to take the most detailed mapping yet. Their findings were that the speech clarity was best in the Odeon of Herodes Atticus and that there is a greater degree of reverberation at Epidaurus due to reflection from the opposing seats.

See also

Notes

- Travlos, 1971, p.537

- C. Calame, Aetiological Performance and Consecration in Taplin and Wyles, The Pronomos Vase and Its Context Oxford, 2010, p.70, "As a simple aetiological hypothesis, one can imagine a threefold etymological pun on the epiklesis of the god to whom the satyric drama is dedicated: Dionysos Eleuthereus, Liberator of men who are free, coming from Eleutherai."

- Plato, Symposium 175e, if taken as a reference to the theatre suggests it could seat 30,000. Pickard-Cambridge, 1988, p.263 dismisses this and states "[a]s reconstructed by Lycurgus, the theatre can have held 14,000-17,000 spectators."

- First correctly located by R. Chandler in Travels in Greece Oxford, 1776. Identified as the Theatre of Bacchus.

- Christina Papastamati-von Moock, The Theatre of Dionysus Eleuthereus in Athens: New Data and Observations on its ‘Lycurgan’ Phase in Csapo et al, 2014, summarizes the archaeological literature p.16 n.2

- Archaeology began in earnest at the site with A. Rousopoulos in 1861. Arch. Ephm. 1862, pp.94-102

- A Dinos by the Sophilos Painter, BM 1971.1101.1, C. Isler-Kerényi, Dionysos in Archaic Greece: An Understanding Through Images, 2007, p.6

- Pickard-Cambridge, 1988, p.58 Thespis' first recorded performance was in 534 BC, see Simon, 1982, p.3

- C. Sourvinou-Inwood, Tragedy and Athenian Religion, Lexington, 2003. p.103. However, W. R. Connor, City Dionysia and Athenian Democracy 1990 argues the Dionysia was created during the Kleisthenic reform.

- Schol. ad Ar. Thesm. 395-6, Suda s.v. ikria. J. Scullion, Three Studies in Athenian Dramaturgy, 1994, p.54-65

- Pickard-Cambridge, 1946, p.14?It is a point of contention whether the irkia that collapsed were at the Agora or the Akropolis.

- Designated H-H in the archaeological literature. It was perhaps both a retaining wall for the orchestra and peribolos for the sanctuary. Travlos, 1971, p.537

- Dorpfeld conjectured a circular orchestra of 24-27m from the arc of masonry discovered. However, Carlo Anti posited a quadrilateral shape to the choral space and a polygonal auditorium. See Powers, 2014, p.13 ff for discussion of the competing views.

- Designated SM1 in the archaeological literature, see Pickard-Cambridge, 1946, p.6

- Pickard-Cambridge, 1946, p.9

- Pickard-Cambridge, 1946, p.11-14. Recent excavation has revealed post-holes for ikria, see R. Frederiksen et al, The Architecture of the Ancient Greek Theatre, 2015, pp.52-55.

- O. Taplin, The Stagecraft of Aeschylus, Oxford, 1977, p.459

- C. Papastamati-von Moock, The Wooden Theatre of Dionysos Eleuthereus in Athens, in R. Frederiksen et al, The Architecture of the Ancient Greek Theatre, 2015.

- O. Taplin, The Stagecraft of Aeschylus, Oxford, 1977, Appendix B, for a description of the stage resources.

- O. Taplin, The Stagecraft of Aeschylus, Oxford, 1977, p.443

- ex. Getty, Malibu, 85.AE.102. O. Taplin, Pots and Plays, Getty, 2007. p.181

- Pausanias 1.20.3

- Pickard-Cambridge, 1946, p.20. See also O. A. W. Dilke, The Greek Theatre Cavea, The Annual of the British School at Athens, Vol. 43 (1948), pp. 125-192.

- The dating of the New Temple is rather more problematic than that. See Kenneth D. S. Lapatin, Chryselephantine Statuary in the Ancient Mediterranean World, 2001, pp.98-105.

- Pickard-Cambridge, 1946, p.17

- Pickard-Cambridge, 1946, p.69

- Pickard-Cambridge, 1946, p.23

- Pickard-Cambridge, 1946, p.24

- Pickard-Cambridge, 1946, p.68

- K. Rees, The Function of the ΠΡΟθΥΡΟΝ in the Production of Greek Plays Classical Philoogy, April 1915, Vol. X N.2, pp.117-138

- Ion lines 184-236

- Naples H.3246 inv.82267. See A.D. Trendall, The Mourning Niobe, Revue Archéologique Nouvelle Série, Fasc. 2, Études de céramique et de peinture antiques offertes à Pierre Devambez, 2 (1972), pp. 309-316. Perhaps related to Aeschylus' Niobe.

- The Boston Thersites Krater. Boston 03.804, Trendall RVAp II, p.472, no.17/75.Apulian, resembles the Varrese Painter, c.340 BC. Perhaps related to Chaeremon's Achilles, See A.D. Trendall, T.B.L. Webster, Illustrations of Greek Drama, Phaidon, 1971, III.4,2.

- Pickard-Cambridge, 1946, p.99

- Pickard-Cambridge, 1946, p.100 ff

- The throne has an inscription from early third c. IG II2 1 923, see Richter, 1966, p.30

- Pickard-Cambridge, 1946, p.138

- Barclay V. Head, A Catalogue of the Greek Coins in the British Museum: Attica, Megaris, Aegina p.110; Plate XIX, 8. London, 1888.

- Pickard-Cambridge, 1946, p.139

- Pickard-Cambridge, 1946, p.141

- Richter, 1966, pp.31-32, pls.150-151

- Pickard-Cambridge, 1946, p.148

- Pickard-Cambridge, 1946, p.156 ff

- From Aristotle Poetics xviii, 1456, a 25-30. See Pickard-Cambridge, 1946, p.161 ff

- from E. R. Fiechter, Die baugeschichtliche entwicklung des antiken theaters; eine studie, Munchen, 1914. pl.63.

- Pickard-Cambridge, 1946, p.175ff

- Göttingische Gelehrte Anzeigen, 1906, p.614

- Lara O’Sullivan, The Regime of Demetrius of Phalerum in Athens, 317–307 BCE, Brill, 2009, p.168. The agônothetês replaced the choregia.

- Pickard-Cambridge, 1946, p.240

- Pickard-Cambridge, 1927, p.79-80

- Pickard-Cambridge, 1946, p.204

- De Architectura, Book V, chapter 6, 8.

- Onomasticon, 4.126-7, see R. C. Beacham, The Roman theatre and Its Audience, Harvard, 1991, pp.176-178.

- Pickard-Cambridge, 1946. pp.234-239

- Pickard-Cambridge, 1946, p.247

- IG II2 3182, see Pickard-Cambridge, 1946, p.248

- Pickard-Cambridge, 1946, p.258

- Pickard-Cambridge, 1946, p.258. See Philostratus VA 4.22

- Travlos, 1971, p.538

- W.Dörpfeld, E.Reisch, Das griechische Theatre, Athen, 1896

- Roselli, 2011, p.21

- Roselli, 2011, p.44.

- Roselli, 2011, p.46

- Martin Revermann, The Competence of Theatre Audiences in Fifth- and Fourth-Century Athens, The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 126 (2006), pp. 99-124

- 1451b23-6

- Roselli, 2011, p.119

- Pickard-Cambridge, 1988, pp.266-268. The history of the theorikon is not clear, Pericles might have instituted it but was certainly established by the time of Demosthenes.

- J. Henderson, Women and the Athenian Dramatic Festivals, Transactions of the American Philological Association, Vol. 121 (1991), pp. 133- 147

- Simon Goldhill, Representing Democracy: Women at the Great Dionysia in Ritual, Finance, Politics: Athenian Democratic Accounts Presented to David Lewis, R. Osborne, S. Hornblower (eds), Oxford, 1994.

- Powers, 2014, p.29 ff summarises the competing views.

- Jens Holger Rindel, Martin Lisa Gade, The Erato Project and Its Contri̇buti̇on to Our Understandi̇ng of the Acousti̇cs of Anci̇ent Greek and Roman Theatres, 2006

- A.Gade, K.Angelakis, Acoustics of ancient Greek and Roman theatres in use today, The Journal of Acoustical Society of America, Vol. 20, n.5, 2006, 3148-3156

- S. Psarras et al, Measurements and Analysis of the Epidaurus Ancient Theatre Acoustics, Acta Acustica United With Acustica, Vol. 99 (2013) 30–39

- C. Hak et al, Project Ancient Acoustics Part 2 of 4: large-scale acoustical measurements in the Odeon of Herodes Atticus and the theatres of Epidaurus and Argos, ICSV23, Athens (Greece), 10–14 July 2016

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Theatre of Dionysus. |

- Arnott, Peter D. An Introduction to the Greek Theatre, Macmillian, 1959.

- Arnott, Peter D. Public and Performance in the Greek Theatre. Routledge, 1989.

- Bieber, Margarete. The History of the Greek and Roman Theatre. Princeton, 1961.

- Camp, John M. The Archaeology of Athens. Yale, 2001.

- Chourmouziadou, K., Kang, J.. Acoustic Evolution of Ancient Greek and Roman Theatres. Applied Acoustics, Volume 69, Issue 6, June 2008, pp. 514–529.

- Csapo, Eric, et al (eds), Greek Theatre in the Fourth Century B.C. De Gruyter, 2014.

- Dinsmoor, William Bell. The Architecture of Ancient Greece. Batsford, 1950.

- Hanink, Johanna, Lycurgan Athens and the Making of Classical Tragedy, Cambridge, 2017

- Pickard-Cambridge, Sir Arthur Wallace, Dithyramb, Tragedy, and Comedy. Oxford, 1927.

- Pickard-Cambridge, Sir Arthur Wallace, The Theatre of Dionysus in Athens, Oxford, 1946.

- Pickard-Cambridge, Sir Arthur Wallace, The Dramatic Festivals of Athens, Oxford, 2nd, revised edition 1988.

- Powers, Melinda. Athenian Tragedy in Performance: A Guide to Contemporary Studies and Historical Debates. Iowa, 2014.

- Rehm, Rush. Greek Tragic Theatre. Routledge, 1994.

- Richter, G. M. A. The Furniture of the Greeks, Etruscans, and Romans. Phaidon, 1966.

- Roselli, David K. Theater of the People: Spectators and Society in Ancient Athens. Texas, 2011.

- Simon, Erika, The Ancient Theatre. Methuen, 1982.

- Simon, Erika, The Festivals of Attica: An Archaeological Commentary. Wisconsin, 1983.

- Travlos, John. Pictorial Dictionary of Ancient Athens. Thames and Hudson, 1971.

- Wiles, David. Tragedy in Athens: Performance Space and Theatrical Meaning. Cambridge, 1997.

- Wilson, Peter (ed). The Greek Theatre and Festivals: Documentary Studies. Oxford, 2007.

.jpg.webp)