Thomas Sinclair (politician, 1838–1914)

Thomas Sinclair (23 September 1838 – 14 February 1914), was an Ulster-Scots businessman and politician who drafted the Ulster Covenant.[1]

Thomas Sinclair | |

|---|---|

| Born | 23 September 1838 Belfast, County Armagh, Ireland |

| Died | 14 February 1914 (aged 75) Hopefield House, Belfast |

Early life and family

Thomas Sinclair was born in Belfast on 23 September 1838. His parents were Thomas (1811–1867), merchant and shipowner, and Sarah Sinclair (1800–1849) (née Archer). Sinclair's father went into business with his brother John (1808–1856), setting up a provisions and general merchant store at 5–11, Tomb Street, Belfast. John married Eliza Pirrie, the relative of the prominent ship builder William Pirrie, 1st Viscount Pirrie. After the death of his father, Sinclair inherited £35,000 as his mother, brother and sister were all deceased.[1]

In 1876, Sinclair married Mary Duffin of Strandtown Lodge, Belfast.[1] They had a daughter, Frances Elizabeth Crichton, and a son.[2] She died in 1879. He married Elizabeth Richardson in 1882. She was the niece of John Grubb Richardson and the widow of Sinclair's cousin, John M. Sinclair. They had three sons and two daughters.[1]

Career

Sinclair attended Royal Belfast Academical Institution and Queen's College Belfast, graduating with a BA with a gold medal for mathematics in 1856, and an MA with gold medals in logic, political economy, and English literature in 1859. After his father's death, Sinclair took over running the family business. He expanded and grew it by merging it with another large provisions business with American branches, Kingan & Co. Sinclair was related to the Kingans through his cousin Sarah, who was married to the owner, Samuel Kingan.[1][3]

Role in politics

Despite numerous requests, Sinclair never stood for parliament, instead he served as Deputy lieutenant, Justice of the peace, president of the Ulster chamber of commerce in 1876 and 1902, and privy councillor in 1896. Having been a supporter of William Ewart Gladstone, Sinclair joined the Ulster Liberal Party in 1868, supporting the land acts of 1870 and 1881. Following the home rule bill of 1886, he convened a meeting in the Ulster Hall of liberals on 30 April 1886 which passed a resolution in condemnation of the bill. Forming the Ulster Liberal Unionist Association, of which he was chair, he organised the Ulster Convention in Belfast. Held on 17 June 1892, it saw 11,879 Ulster unionists meet to protest home rule. 9 months after the Convention, Sinclair was appointed to the executive committee of the new unionist clubs, which were founded to protect the union. The defeat of the British Liberal party in 1895 significantly decreased the threat of home rule, leading to the unionists clubs being suspended, and Sinclair returning to his activities in liberal reform. He was the leading Ulster member of the recess committee from 1895, which was founded by Horace Plunkett. He supported Plunkett's backing of T. P. Gill as secretary of the Irish Agricultural Organisation Society in 1899, in the face of strong protest by conservative unionists.[1][4]

Despite his unionist politics, Sinclair was non-sectarian, and during his time as chairman of the convocation of the Queen's University he defended the core non-sectarian principles of the institution, and refused to allow any form of denominational teaching. Through his work with the recess committee, he ensured that the new Department of Agriculture's vocational and technical education would remain secular.[1]

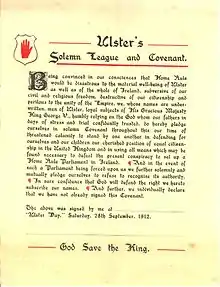

By 1904 and the devolution crisis, Sinclair sided with conservative unionists, being of the 30 members of the standing committee of the Ulster Unionist Council on its foundation in December 1904. He proposed that all suspended unionist clubs be reestablished in January 1911, with the purpose of increasing their membership and responsibilities. This resulted in the clubs taking up arms, with over 80 groups drilling by April 1911, which would go on to form the core of the Ulster Volunteers. On 25 September 1911, Sinclair was appointed to a five-man commission tasked with writing a constitution for a provisional government of Ulster. He was one of the contributors to the 1912 collection of essays from the unionist party, Against home rule. He identified the six county Ulster, proffering the idea of a two-nation island, warning that Ulster would never form part of an independent Ireland. Later in 1912, he was tasked with drafting Ulster's Solemn League and Covenant, a pledge for signatories to oppose and defeat home rule and never recognise an Irish parliament.[1][3][4]

Sinclair died on 14 February 1914 at his home, Hopefield House, Belfast. His funeral procession on 18 February was headed by 200 UVF officers. The Ulster Museum holds a portrait of Sinclair by Frank McKelvey,[1] and QUB holds one by Henrietta Rae.[5] A memorial window at Church House, the headquarters of the Presbyterian Church, was unveiled in Sinclair's memory on 8 June 1915, and there is a Sinclair Memorial Hall opened in his honour on 10 September 1915. A blue plaque was erected to Sinclair on the Duncairn Centre.[4]

The Sinclair Ward in the Royal Victoria Hospital, Belfast was originally funded by Sinclair's father, in honour of his wife Sarah under the Sinclair Memorial Fund. The surgeon and politician Thomas Sinclair was also a relative.[6]

References

- Hourican, Bridget (2009). "Sinclair, Thomas". In McGuire, James; Quinn, James (eds.). Dictionary of Irish Biography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Doak, Naomi (2016). "'The blind side of the heart': Protestants, politics, and patriarchy in the novels of F.E. Crichton". In Pilz, Anna; Standlee, Whitney (eds.). Irish women's writing, 1878-1922 : advancing the cause of liberty. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 9781526100757.

- "Ulster Scots who shaped Ulster" (PDF). Ulster Scots Agency. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- "174 Trust: Duncairn Centre - Thomas Sinclair Memorial Plaques". Great Place North Belfast. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- "The Right Honourable Thomas Sinclair (1838–1914) | Art UK". artuk.org. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- Clarke, RSJ (April 1994). "A Corridor to the Past". The Ulster Medical Review. 63 (1): 85–86.