Tianguis

A tianguis is an open-air market or bazaar that is traditionally held on certain market days in a town or city neighborhood in Mexico and Central America. This bazaar tradition has its roots well into the pre-Hispanic period and continues in many cases essentially unchanged into the present day.[1] The word tianguis comes from tiyānquiztli in Classical Nahuatl, the language of the Aztec Empire.[2] In rural areas, many traditional types of merchandise are still sold, such as agriculture supplies and products as well as modern, mass-produced goods. In the cities, mass-produced goods are mostly sold, but the organization of tianguis events is mostly the same.[2][3] There are also specialty tianguis events for holidays such as Christmas as well as for particular types of items such as cars or art.[4][5]

History

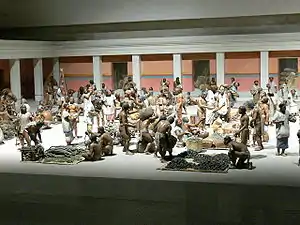

The tradition of buying and selling in temporary markets set up either on a regular basis (weekly, monthly, etc.) is a strong feature in much of Mexican culture and has a history that extends far back into the pre-Hispanic period.[1] It was the most important form of commerce in the pre-Hispanic era, and after the Spanish Conquest, the Europeans mostly kept this tradition intact.[6] Market areas have been identified in ruins such as El Tajín in Veracruz, and a number of pre-Hispanic towns were initially founded as regional markets, such as Santiago Tianguistenco and Chichicastenango, Guatemala .[2] The word tianguis derives from the Nahuatl word tiyānquiztli 'open air-market', from tiyāmiqui 'to trade, sell'. The most important markets, such as the one in Tlatelolco, were set up and taken down every day of the week. This market served about one fifth of the population of Tenochtitlan (Mexico City) before the Conquest and had its own governing system, which included a panel of twelve judges to resolve disputes.[6] Today, one of the most visited exhibits in the National Museum of Anthropology is the model of the pre-Hispanic market such as the one in Tenochtitlan.[2]

From the time of the Conquest to the present, many tianguis, especially in rural areas, have continued to operate much in the same way as before, with only changes in merchandise that reflect changing customer needs.[7] In the cities, especially Mexico City, the history of these markets is filled with examples of attempts to regulate them and push them away to other places, with mixed success. The Zócalo, or main plaza of Mexico City, was the scene of a number of efforts to clear the area of ambulantes, street vendors, and establish permanent markets in or near the plaza such as the Parian. In all these cases, vendors eventually retook the plaza[8] This problem was again tackled in the 1990s as part of an effort to revitalize the historic center of Mexico City. Despite much initial resistance, the area has been free of street peddlers since that time.[9] Much of the tianguis' business that used to be done in the Zocalo has now moved to other places such as the Tepito neighborhood.[10]

In the 20th century, local governments in Mexico have promoted municipal or public markets or mercados to better regulate the selling of goods traditionally available in tianguis. In Mexico City, some of the better known of these markets are La Merced, Abelardo L. Rodriguez Market and Mercado Lagunilla.[11] La Merced is located in an area that had been a huge tianguis for most of the colonial period as it was located at the edge of a lake (now drained).[12] The Abelardo L. Rodriguez Market was specifically built by the government in the 1930s to try to “modernize” the sale of produce and other staples. It went as far as having a daycare center and a theater and commissioning Diego Rivera to supervise the painting of murals inside. These murals can still be seen today.[13][14] However, these efforts have not eliminated the tianguis tradition; in fact, the number of such informal markets (5,836,000) far surpasses the number of mercados (2,810,000). In Mexico City alone, there are 317 mercados versus 1,357 tianguis. One reason is that many of these mercados are not well-maintained and few new ones have been built since the 1970s.[11]

The tianguis is part of the so-called “informal economy”[15] even though many of the “informal” vendors are well enough known and established to offer services such as layaway.[1] While many establish stores consider the tianguis to be damaging to their businesses,[15] many Mexican consumers see both sectors as complementary.

Surveys of consumers have shown that many Mexicans buy from tianguis because of the frequent lack of bargains, social interaction, and customer service in formal stores. According to one survey, over 90% stated that they have bought merchandise from a tianguis, with the average family spending about 300 pesos per visit. The most common items sold in tianguis include groceries, beauty supplies, clothing, appliances, electronics, prepared foods, tools and used goods.[1] About a third of Mexicans buy at least some of their clothing and shoes in tianguis.[15]

Operation

In the most traditional of tianguis, public officials will close off a street to vehicle traffic on a specified day so that merchants (called “ambulantes”) can set up their spaces on the sidewalks and/or roadways. Most of the spaces are covered by plastic tarps to protect sellers and vendors from the sun and/or the rain. They often enclose the entire area, giving the market an enclosed feeling. In many rural and smaller towns, there is usually a preferred area, which is usually in the town center, near the church plaza and permanent market.[16]

In larger cities, the market exists, often in places with no supermarkets or mercados nearby.[3] Neighbors and permanent merchants in the Del Valle neighborhood of Mexico City see the weekly tianguis as a benefit. It brings basic staples such as vegetables, fruit, clothing as well as crafts and traditional sweets to a neighborhood that does not have a permanent market or supermarket. For permanent merchants, the tianguis brings increased foot traffic to the area.[17] Many crowd around established markets or “mercados” such as La Lagunilla in Mexico City. In cases such as these, vendors set up stalls everyday, but the area is most crowded on weekends. On Saturdays in La Lagunilla, stands selling leather, coats and jackets, vintage clothes and other items crowd the streets.[18]

Some tianguis are private spaces, which usually contain both permanent buildings and open areas for stalls. One example of this is El Sol in Zapopan, Jalisco, where the vendors in the permanent area operate all week and the tianguis area is mostly occupied on weekends.[19] Most tianguis operate more according to tradition than by formal rules. All have some kind of administrator or administration committee. The job of administrators is to interact with local authorities on behalf of tianguis sellers and manage internal affairs, especially the assignment of spaces and the collection of rental fees.[19][20] The first rule is the process of negotiating for a space, but often this includes the denial of spaces for those who are unknown to the administration. Another is for vendors to watch out for authorities and warn others of authorities who may come to inspect sellers.[20] In some markets, bartering is making a comeback, especially in the rural areas, such as the northeast of Morelos state. In one market in Zaculapan, 150 of 400 vendors state that they accept bartered goods, especially in produce and staple food products such as milk and bread. One reason for this is that many rural families lack cash, but raise produce for sale on their own farms and orchards. This tradition has existed for centuries, but increases in hard times.[21]

Vendor spaces can be as simple as a cloth on the ground to a simple table or pile of boxes to tables with walls made up of interconnecting metal poles. Those who sell goods from the ground may have only a few things to sell or their cloth might be filled to the edge. Those with a table have the advantage of having their goods in easier reach of both buyer and seller. Merchandise from these spaces is usually produce, hats, jewelry, pottery and other small, unbreakable items. Stalls with walls allow for the hanging of merchandise such as clothing or the addition of shelves for more delicate wares. These type of stalls can display six times the merchandise than those who sell from the ground or table.[16]

Most goods sold in tianguis are small items that customers can carry away. In many of these markets, vendors selling similar items group together. This has advantages for both buyer and seller, as it provides a wider variety of products than would a single merchant. It also lets shoppers know where to find a particular item. Certain goods are more prone to this such as produce, meat, and certain specialized or craft items. However, exceptions to this occur because a vendor cannot afford space in the area or because he or she is looking for convenience shoppers who are not looking to bargain. Most tianguis sellers, especially produce sellers, arrange their wares in certain arrangements, such as in baskets, or into neat piles to make their wares more attractive.[16]

Rural tianguis

The tianguis in rural areas most closely resemble those of centuries past.[2] Most still contain a large amount of agricultural supplies, produce and other food staples, livestock, handmade items and traditional clothing. In many, indigenous languages such as Nahuatl and Zapotec can be heard. One example is the Sunday market of Cuetzalan, Puebla, where Nahuatl speaking people can be heard negotiating prices on items such as vanilla beans, handcrafted textiles, huipils, coffee, flowers and baskets much as their ancestors did.[2] The Tlacolula Sunday market in Oaxaca is the largest and busiest in the central valleys area of the state, and brings people from the very rural areas into town to both sell and buy. The market fills an important retail and social gap as most of the outlying villages are too small to support permanent stores and many use the opportunity to converse with distant neighbors. Even sellers will consider who they want to socialize with when choosing a selling space.[16] The tianguis of Chilapa, Guerrero attracts thousands of Nahua and Tlapaneco people, who come to buy and sell handcrafts, medicinal plants, local specialties such as pozole and many other items. Many of the visitors are from neighboring regions. Prices are low. It is possible to buy a liter of mezcal for only 25 pesos.[7] The weekly Thursday market in Villa de Zaachila is divided into three parts, one devoted to firewood, as many still cook with it, one to livestock and the rest to basic staples.[22] While many of the goods sold in rural markets are similar to those sold for centuries, modern items such as mass-produced tools, clothing such as jeans, CDs, DVDs and automobiles are also sold.[7][16]

City tianguis

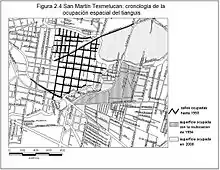

The organization and function of most city tianguis are mostly the same as those in rural areas; however merchandise varies somewhat and there are problems associated with holding this type of event in the more crowded city. One of the oldest continually operating tianguis in Mexico is the one in Cuautitlán, just outside Mexico City, which has been going on every Tuesday for over 500 years. The market was established in 1491 by the Chichimecas when this area was rural and a way station between Mexico City and points north. Since then, Cuautitlan has become a crowded part of Greater Mexico City, but the tianguis is still in the same place and operated more or less in the same manner. This market congregates 7,500 vendors from various municipalities and states such as Michoacán, Puebla, Pachuca and the municipalities of northern Mexico State. It extends over 250,000 m2. There are efforts to move it away from the center and near the municipal border with Tultitlán, but the merchants have refused to be moved.[23]

Due to the change in tastes needs of customers, urban tianguis focus on different merchandise. Produce and other basic staples are still offered, but other items are far more likely to be manufactured items such as electronics, name brand clothing and other wares. Relatively few crafts or agricultural items are offered in most city tianguis.[23] Merchandise mostly concentrate on more modern and manufactured items, such as clothing, purses, beauty products, electronics and hand appliances. Those who sell audio and video CDs, a lucrative business, will often have large loudspeakers playing samples of their wares at very high volume.[6]

Mexico’s two largest cities, Mexico City and Guadalajara, have large number of tianguis that employ many people. Officially, Guadalajara has 143 registered tianguis in the city, with no new ones approved since 1997. These tianguis have over 40,000 stalls combined. These stalls pay a nominal fee of between 2.5 and 3 pesos per square meter for the right to be there.[24] About half of the tianguis in Guadalajara operate once a week, about 15% every two weeks and the rest about once a month. In Guadalajara, it is estimated that approximately 95,000 people work in this sector.[1]

In Mexico City, there are 1,066 officially recognized tianguis controlled by 600 tianguis associations, each of whom has between forty and six hundred members. Hundreds of these close entire streets at least one day a week. These tianguis employ about 130,000 people.[3] These markets are regulated by the Secretaria de Desarrollo Economico and by the Secretaria de Economia Federal. Most tianguis vendors are located in the borough of Iztapalapa, where they make up about one third of the total. This borough contains 304 tianguis markets convene during the week with Gustave A. Madero coming second with 160. Sunday is the busiest day for tianguis, and Tuesday is the slowest.[3]

The largest tianguis in Mexico City is San Felipe de Jesus, which is located on the border of Gustavo A. Madero and Tlalnepantla. This market has been in operation for over forty years, covers 17 km and has 17,000 merchants, which offer their wares from Tuesday to Saturday. This is one of the least governmentally supervised markets due to the fact that it stretches over both the Federal District and the State of Mexico.[3][25]

Local governments have the authority to inspect and regulate the businesses that operate in tianguis.[26] Regulations such as Article 52 of the Reglamento Interior de la Administration Publica of the Federal District, are supposed to regulate when and where these events take place as well as inspecting locales and products for sale.[24][27] Vendors can be removed if they exceed the limits set, but many cities have trouble enforcing this, leading to traffic jams.[24][28] Regulation, such as the checking of scales, and cooking equipment in food stalls, is scarce.[6] Vendors in tianguis are liable under all consumer protection laws as well.[29] However, many authorities readily admit that they do not have the manpower to enforce laws and regulations in large, crowded and numerous tianguis, although raids are performed sporadically, especially looking for stolen and counterfeit merchandise.[30][31] Stolen merchandise, especially electronics, and unauthorized CDs and DVDs is the largest criminal activity found in tianguis, with copying of CDs and DVDS one of the most lucrative businesses.[20][30][31] Tianguis sellers can be quite sophisticated. According to Iztalapalpa officials, vendors at the El Salado tianguis set up shop as early as 4 or 5 am in order to receive stolen and other merchandise from trucks behind the Unidad Habitacional Concordia Zaragaza housing complex, and use radios to communicate and watch out for authorities Officials claim there are at least ten places in the market that sell drugs and two that sell guns. Much of the allegedly stolen merchandise consists of computer equipment and handheld gadgets such as iPods. The sale of stolen merchandise such as this is popular because it can cost about half of what it does in legal channels.[11] Counterfeit perfumes are a specialty of the tianguis Del Rosal in Colonia Los Angeles. Empty bottles of the real merchandise are bought by the vendors and then filled with the counterfeit perfume.[27] PROFECO, Mexico’s consumer protection agency, advises strong caution when shopping in tianguis as it is extremely difficult to help those who have been a victim of fraud.[29] Another problem is the sale of vehicles that are stolen or illegally imported from the United States. This problem is serious enough to warrant the vigilance of the Procuraduria General de Justicia of Mexico City and special warnings by PROFECO.[4][29][32] Restricted items such as medicines, cigarettes and alcohol are also openly sold. Other available restricted merchandise includes fireworks, blades, knives, pornography, endangered species, and smuggled goods. Other articles include hoods, tear gas, fake guns, and sometimes even real guns. Medicines from the government health service can be found in El Salado, which is held on Wednesdays on Calzada Zaragosa. Patches and uniforms from services such as city police and firemen, as well as the electric company and Telmex can be found as well.[27] Lastly, pickpocketing and assault on both merchants and customers is not unknown.[25]

Many tianguis have problems in the neighborhoods they occupy. These events are accused of “devouring” streets as regulated and non/regulated ones grow and multiply.[6] The main problem with tianguis is that merchants spread out their wares over sidewalks and other public spaces beyond where they are authorized, blocking pedestrian and vehicular traffic. These places can measure four by four meters on city streets.[26] Monterrey Street in the Del Valle neighborhood of Mexico City is cut from six lanes to three lanes on tianguis days.[17] Another problem is that they block scarce parking space.[28] Residents complain about noise and odor. Lastly, at the end of the day after the stands are taken down and brought home, tons of garbage is left behind, and in areas where market activity is frequent, infrastructure such as light poles and sidewalks are damaged.[6][33]

Despite the problems and despite the fact that tianguis merchants do not pay taxes, rent or services (however bribes are paid to many city officials[34]) like established businesses do, eliminating them or even moving them is very difficult due to the large number of people they employ and their firm place in the culture.[1] Attempts to remove illegally placed merchants or move tianguis entirely generally meet with protest.[6] For about 34 years, the area around the permanent Mercado Juarez had been the scene of one of the largest tianguis in the city of Toluca, operating more or less every day. On weekends, the number of vendors was as high as 2,800. More than 1,100 police were needed to forcibly remove 560 stands from the triangular plaza in front of Mercado Juarez and the four blocks surrounding it. To prevent the vendors from returning, the entire plaza was back hoed and a large fence installed around the plaza. Police patrolled it and the four-block area for weeks afterwards. While there was no violence, tensions were high and there were verbal protests. The clearing of this tianguis was done to alleviate traffic problems in this part of the city, with vendors offered new space at the site of the old airport.[35] In some areas, such as Tepito in Mexico City, almost the entire neighborhood is employed as informal merchants with even more that come in to sell.[34][36] This market has a long tradition here and is the largest and most vibrant in the city in the 21st century.[10]

Specialty tianguis

Many occasional and some semi permanent tianguis are specialty markets, either specializing in one type of good or are set up for a specific season. One semi permanent market is the “Fashion Tianguis,” with about fifty vendors who sell clothing each weekend at Parque México in Mexico City. Most are true designer labels from various countries, including Mexico. Merchandise includes many ítems that have not sold in upscale stores. Other tianguis that specialize in fashion include Plaza Cibeles on weekends, La Lagunilla on Sundays, and Del Chopo on Saturdays. The last specializes in “dark” and Gothic fashion .[37] The city of Tonalá, Jalisco, sponsors a tianguis adjacent to the permanent market, which is restricted mostly to vendors who sell locally made pottery and other craft items. It is called the Tianuges de Artesanos.[38] A number of cities such as Monterrey, and Guadalajara have tianguis that operate only to sell used cars.[4][39]

The open air art market of San Ángel has occurred every Saturday morning since 1964 and sells mostly traditional and indigenous fine arts, created in Mexico. It is located in a tiny park named Plaza Tenanitla and is the oldest art market in Mexico City.[5] Some of the artists and artisans are the children and grandchildren of the original founders of the market. While many of the artists live in Mexico City, a number travel from as far as the states of Puebla, Guerrero and Mexico State to sell. It is informally known as the Saturday Bazaar, but the association that runs it formally calls it the tianguis Artesanal Tenanitla. Most of the stalls still sell paintings and sculptures but other also sell crafts, snacks and antiques.[5]

Seasonal tianguis serve needs for holidays and other annual events. In San Pablo Tultepec, there is a tianguis of fireworks in August and the first part of September before the annual Independence Day celebrations in Mexico. It is located on the entrance to the town from the highway between Toluca and Mexico City. Everything from sparklers to complicated sets with moving parts are sold. This market operates with licenses from the State of Mexico as well as from the Secretariat of National Defense.[40] In Saltillo every Thursday during Lent, there is a tianguis devoted entirely to fish and seafood, partially sponsored by the federal Secretariat of Agriculture, Livestock, Rural Development, Fisheries and Food agency.[41] A number of municipalities, such as Hermosillo, Tepic, Xalapa and Celaya, sponsor tianguis for back-to-school, in order to allow parents to buy uniforms, school supplies and other needs at lower prices. Credit is also offered to customers at these events.[42] The most important seasonal tianguis are for the Christmas holiday season, which runs from late November to January 6. From near Christmas Eve up until Epiphany, many of these stalls are open from early in the morning to very late at night. Most of the merchandise revolves around items for nativity scenes and Christmas trees. Trees are sold as well, with taxis and men with hand trucks nearby to hire.[43][44]

Some tianguis can be a tourist attraction in themselves. Every year the indigenous and folk art tianguis is held in Uruapan during Holy Week, which is a major vacation time in Mexico. Over twelve hundred artisans come to the city on the large main plaza to sell. The promotional literature states that it is the largest tianguis of its kind in the Western Hemisphere, and is accompanied by arts contests, parades and banquets. This event is one of the top five for the state of Michoacan and accounts for 15% to 20% of the income this small city makes each year.[45]

See also

References

- Orihuela, Gabriel (February 12, 2001). "El Comercio Informal: entre negocio y cultura" [The Informal Economy: Between business and culture]. Mural (in Spanish). Guadalajara, Mexico. p. 1.

- Rios, Adalberto (May 14, 2006). "Ecos de Viaje / De tianguis y mercados" [Travel echos/Of tianguis and markets]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 14.

- Padgett, Humberto (December 9, 2004). "Invaden tianguis las calles" [Tianguis invade streets]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 4.

- Marquez, Deyanira (May 21, 2001). "Uno de cada 10 autos es 'chocolate' en los tianguis" [One of ten autos is illegally imported in the tianguis]. Mural (in Spanish). Guadalajara, Mexico. p. 6.

- Sorrentino, Joseph (Mar–Apr 2010). "Mexico City's Oldest Traditional Art Market". Americas (English Edition). Washington, DC. 62 (2): 58–60.

- Velazquez, Francisco (September 24, 1999). "Reordenaran tianguis: Desactivaran anarquia" [Reorganize tianguis:disactivate anarchy]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 8.

- Guerrero, Jesus (July 12, 2004). "Revive tianguis venta artesanal" [Tianguis revives crafts sales]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 28.

- Enciclopedia de Mexico. 16. Mexico City: Encyclopædia Britannica. 2000. pp. 8273–8280. ISBN 978-1-56409-034-8. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Noble, John (2000). Lonely Planet Mexico City:Your map to the megalopolis. Oakland CA: Lonely Planet. ISBN 1-86450-087-5.

- "Tepito, heredero de los baratillos" [Tepito, inheritance of baratillos] (in Spanish). Mexico: Ciudadanos en red. Archived from the original on 2014-03-18. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- Ramirez, Karla (July 6, 2005). "Rebasan tianguis a mercados" [Tianguis surpass permanent markets]. El Norte (in Spanish). Monterrey, Mexico. p. 2.

- Barranco Chavarría, Alberto. "La Merced: Siglos de Comerico". Ciudadanos en Red. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- Gomez Florez, Laura (2008-05-19). "Remodelan el histórico mercado Abelardo L. Rodríguez como parte del rescate del Centro" (in Spanish). Mexico City: La Jornada. Retrieved June 3, 2009.

- "Sobreviven en un mercado murales de discípulos de Diego Rivera" (in Spanish). Mexico City: El Universal. 2007-06-27. Retrieved June 3, 2009.

- Galan, Veronica (January 10, 2007). "Prefieren tianguis para vestirse" [They prefer the tianguis for clothes]. Mural (in Spanish). Guadalajara, Mexico. p. 4.

- Lee, David; Roberts, Charles (Spring 2004). "The Market at Tlacolula". Focus on Geography. New York. 47 (4): 29–34. doi:10.1111/j.1949-8535.2004.tb00048.x.

- Hernandez, Jesus Alberto (September 30, 2002). "Ven tianguis como beneficio" [They see tianguis as a benefit]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 4.

- Aguilar, Lupita (October 15, 2005). "La Lagunilla: Paraiso 'vintage'" [La Lagunilla:Vintage Paradise]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 5.

- "Plantan autoridades a comerciantes del Sol" [Authorities place merchants of Sol]. Mural (in Spanish). Guadalajara, Mexico. March 5, 2006. p. 3.

- Ascencio, Julio (November 4, 2002). "Tianguis metropolitanos: Paraiso de la pirateria" [Metropolitan tianguis:Paradise of pirating]. Mural (in Spanish). Guadalajara, Mexico. p. 12.

- Gonzalez, Hector Raul (July 6, 2008). "Reviven en Morelos trueque en tianguis" [Bartering revived in tianguis in Morelos]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 16.

- Triedo, Nicolás (December 2000). "La Danza de los Zancudos en la villa de Zaachila (Oaxaca)" [The Dance of the Stilts in the village of Zaachila] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Mexico Desconocido magazine. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- Barrera, Griselda; Jorge X. Lopez (June 12, 1996). "Medio siglo de comercio" [Half century of commerce]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 12.

- Castro, Leticia (January 2, 1999). "Registran 143 tianguis" [Register 143 tianguis]. Mural (in Spanish). Guadalajara, Mexico. p. 2.

- Ramirez, Clara (September 5, 2005). "'Vende' inseguridad tianguis de Puebla" [Puebla tianguis "sells" crime]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 22.

- Pilar Perez, Jessica; Margarita Valle; Julio Ascencio (January 24, 2002). "Ordenan revisar tianguis" [Order the revision of tianguis]. Mural (in Spanish). Guadalajara, Mexico. p. 1.

- Cabrera, Liliana (March 12, 2008). "Venden en los tianguis mercancías prohibidas" [Tianguis sell prohibited merchandise]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 2.

- Pilar Perez, Jessica (September 13, 2001). "Impediran crecimiento de tianguis en Tonala" [Preventing the growth of tianguis in Tonala]. Mural (in Spanish). Guadalajara, Mexico. p. 4.

- Rios Garcia, Leticia (April 27, 2000). "Recomienda Profeco no comprar en tianguis" [PROFECO recommends not buying in tianguis]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 10.

- Rosales, Grettel (April 1, 2005). "'Barren' tianguis de discos pirata" ["Sweep" tianguis of pirated disks]. Mural (in Spanish). Guadalajara, Mexico. p. 5.

- Corona, Juan (January 2, 2008). "Vende tianguis armas y droga" [Tianguis sell arms and drugs]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 1.

- Vicenteno, David (March 8, 2001). "Vigilan tianguis de autos" [Watching auto tianguis]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 2.

- Martinez, Paulina; Mariana Jaime; Margarita Valle; Jessica Pilar Perez (January 21, 2008). "Se van tianguis, queda la basura" [Tianguis go, garbages stays]. Mural (in Spanish). Guadalajara, Mexico. p. 3.

- Rico, Maite (2006-06-21). "Tepito, barrio bravo de México" [Tepito, fierce neighborhood of Mexico]. El País (in Spanish). Madrid. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- Espinoza, Arturo; Enrique I. Gomez (October 18, 2006). "Retiran de Toluca puestos ambulantes" [Stalled withdrawn from Toluca]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 18.

- "Tepito, mosaico popular y centro de piratería, pelea con la mala fama" [Tepito: popular mosaic and center of piracy, fights with its bad reputation]. Terra (in Spanish). 2007-10-05. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- Aguilar, Lupita (April 10, 2004). "Toman tianguistas el Parque Mexico" [Tianguis sellers take Parque Mexico]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 7.

- Sepulveda, Pablo (March 20, 2009). "Quieren el tianguis para los artesanos" [They want the tianguis for artisana]. Mural (in Spanish). Guadalajara, Mexico. p. 6.

- Romo, Carmen (January 31, 2008). "Alistan reubicación de tianguis de autos" [Solicit the relocation of the car tianguis]. El Norte (in Spanish). Monterrey, Mexico. p. 5.

- Velasco, Eduardo (August 21, 2001). "Preparan artesanos tianguis de cohetes" [Artisans prepare fireworks tianguis]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 3.

- "Ponen en marcha tianguis de pescados" [Fish tianguis begun]. Palabra (in Spanish). Saltillo, Mexico. March 3, 2001. p. 2.

- Carpio, Maria Dolores (August 17, 1997). "Los tianguis, una opcion" [The tiangus, an option]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 1.

- Alvarado, Alejandro (December 19, 2007). "Convive tradición en tianguis" [Tradition lives in the tianguis]. Mural (in Spanish). Guadalajara, Mexico. p. 10.

- Calderon, Alicia (December 13, 1998). "Autorizan tianguis diario por la Navidad" [Daily tianguis authorized for Christmas]. Mural (in Spanish). Guadalajara, Mexico. p. 2.

- Paul (Pavel) Shlossberg (2008). A Tale of Two Tales: Artisans, Transnational Folklore, Cultural Hierarchies, Social Exclusion, Rural Poverty, and Petty Capitalism in Michoacan, Mexico (PhD thesis). Columbia University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. Docket 3333438.