Tongue River Massacre (1820)

The Tongue River massacre was an attack by Cheyenne and Lakota on a camp of Crow people in 1820. According to some accounts, it was one of the most significant losses of the Crow tribe.[1]:p. 190

| Tongue River Indian massacre | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Cheyenne and Oglala Lakota | Crow Nation | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| The whole Cheyenne tribe, a camp of Lakotas | 100 tipis in camp | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Most likely very few, if any | All the men killed. An unknown number of woman and/or children already taken captive killed | ||||||

Background

The intertribal conflict between the Cheyenne and the Crow predated the arrival of whites in the Yellowstone and Powder River areas.[2]:p. 127 The Lakotas were also enemies of the Crow. The Lakota winter count of Lone Dog gives the year 1800-1801 as the winter when "Thirty Dakotas [Lakotas] were killed by Crow Indians".[3]:p. 273 According to American Horse's winter count, the Lakota retaliated the next year. Several Lakotas, aided by the Cheyenne, killed all the men in a Crow camp with 30 tipis and took the women and children captive.[4]:p. 553

The leadup to the 1820 massacre was a Cheyenne raid in 1819. A Crow camp neutralized 30 Cheyenne Bowstring warriors during a defense of the horse herds.[5]:p. 23

The attack

To avenge the loss of so many young men, the whole Cheyenne tribe carried its sacred arrows, Mahuts, against the Crow the next spring. A Lakota camp joined the war expedition.[4]:p. 553 They camped at Powder River, either in present-day Montana or Wyoming. Crows from a camp at the Tongue River chanced upon them just before dark. The Cheyenne and the Lakota realized they were discovered, and the warriors quickly prepared to make an attack on their foes. Meanwhile, the Crow camp organized a big war party to strike first and drive the enemies out of the Crow country. The two Indian armies crossed each other unnoticed during the night. The Crows lost the track and never found the camps on the Powder River.[5]:pp. 24–25

The Cheyenne and Lakota attacked the unprotected Crow camp at noon. With a camp with only women, children and old men, they were in control right from the start.[2]:p. 130 They killed all the old men, captured the horse herds, took the women and children captive and reduced the camp to rubble.[5]:p. 26 On the way back to Powder River, a disagreement started between the Cheyenne and the Lakota over the division of the more than 100 captives. During the heated discussion, an unknown number of Crow women and children were killed by the warriors.[5]:p. 26

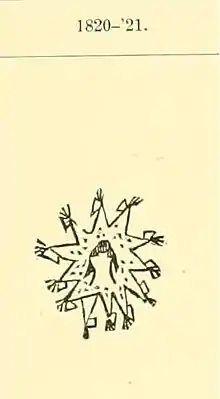

The battle is mentioned in the Oglala Lakota American Horse's winter count. It tells of a Crow camp with 100 tipis. The Lakotas "killed many and took many prisoners".[4]:p. 553, fig. 776

This was likely the most severe blow to the Crow tribe on the battlefield in historic time.[1]:p. 190 [7]:p. 168

Due to the meager sources, it is difficult to name all war leaders and warriors involved in the fighting, provide exact figures of the strength of the camps, or the number of casualties. The attack may sometimes be confused with other big Cheyenne or Lakota victories over the Crow.[2]:pp. 130–133 [8]:p. 55 In 1876, James H. Bradley, chief of Crow scouts gave an account of the battle as understood by him.[9]:p. 179

.jpg.webp)

Consequences

With the 1820 massacre, the Cheyenne and Lakota prevented themselves from ever becoming allies of the Crow, as they tried later during Red Cloud's War against the whites in the 1860s.[8]:p. 91

The following years the devastating defeat resulted in attacks of revenge by the Crows, which the Cheyennes counter-revenged.[5]:p. 27 Cheyenne warrior George Bent visited the scene of the massacre in 1865 with his tribe. It still showed evidence of the destruction in form of broken tipi poles. Here and there, they found old hand weapons of stone in the grass.[5]:p. 26

With time, the Crow blamed the Lakota alone for the attack at Tongue River in 1820. More than 100 years later Crow chief Plenty Coups told about the never forgotten massacre. In his opinion, the Crows had nearly been wiped out "that terrible day" in 1820.[1]:p. 190 Crow woman Pretty Shield expressed the same view while telling about her life and the Crows to Frank B. Linderman.[7]:p. 168

The Cheyenne Indians lost the Sacred Arrows around 1830, when they tried to repeat the victory over the Crow in an attack on a hunting camp of Pawnee Indians.

References

- Linderman, Frank B.(1962): Plenty Coups. Chief of the Crows. Lincoln/London.

- Stands In Timber, John and Margot Liberty (1972): Cheyenne Memories. Lincoln and London.

- Mallory, Gerrick (1893): Picture-writing of the American Indians. Lone-Dog's Winter Count. Tenth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1888-'89. Washington, 1893, pp. 273-287.

- Mallory, Gerrick (1893): Picture-writing of the American Indians. Tenth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1888-'89. Washington.

- Hyde, George E. (1987): Life of George Bent. Written From His Letters. Norman.

- Mallory, Gerrick: The Corbusier Winter Counts." Smithsonian Institution. Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. 4th Annual Report. 1882-'83. Washington, 1886. Pp. 127-146. P. 136.

- Linderman, Frank B. (1974): Pretty Shield. Medicine Woman of the Crows. Lincoln and London.

- Hoxie, Frederick E.(1995): Parading Through History. The making of the Crow Nation in America, 1805-1935. Cambridge.

- Bradley, James H.(1896): Journal of James H. Bradley. The Sioux Campaign of 1876 under the Command of General John Gibbon. Contributions to the Historical Society of Montana, Vol. 2, Helena, pp. 140-227.