Trigger (firearms)

A trigger is a mechanism that actuates the firing sequence of a firearm, airgun, crossbow, or speargun. A trigger may also start other non-shooting mechanisms such as a trap, a switch or a quick release. A small amount of energy applied to the trigger causes the release of much more energy.

In "double action" firearm designs, the trigger is also used to cock the firearm—and there are many designs where the trigger is used for a range of other functions. Although triggers usually consist of a lever actuated by the index finger, some such as the M2 Browning machine gun or the Iron Horse TOR (thumb operated receiver) use a thumb-actuated design, and others like the Springfield Armory M6 Scout use a "squeeze-bar trigger" similar to the ticklers on medieval European crossbows.

Function

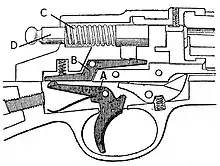

Firearms use triggers to initiate the firing of a cartridge seated within the gun barrel chamber. This is accomplished by actuating a striking device through a combination of spring (which stores elastic energy), a trap mechanism that can hold the spring under tension, an intermediate mechanism to transmit the kinetic energy from the spring releasing, and a firing pin to eventually strike and ignite the primer. There are two primary types of striking mechanisms — hammer and striker. A hammer is a pivoting metallic component subjected to spring tension so when released will swing forward to strike a firing pin like a mallet hitting a punch/chisel, which then relays the hammer impulse by moving forward rapidly along its longitudinal axis. A striker is essentially a firing pin directly loaded to a spring, eliminating the need to be struck by a separate hammer. The firing pin/striker then collides into the cartridge primer positioned ahead of it, igniting the propellant powder within the cartridge case and discharges the bullet. The trapping interface between the trigger and the hammer/striker is typically referred to as the sear surface. Variable mechanisms will have this surface directly on the trigger and hammer or have separate sears or other connecting parts.

Stages of a trigger pull

The trigger pull can be divided into three mechanical stages:

- Takeup or pretravel: The movement of the trigger before the sear moves.

- Break: The movement of the trigger during the sear's movement up to the point of release, where the felt resistance suddenly decreases.

- Overtravel: The movement of the trigger after the sear has already released

Takeup

When considering practical accuracy of a firearm, the trigger takeup is often considered the least critical stage of the trigger pull. Often triggers are classified as either single-stage or two-stage based on the takeup.

- Single-stage triggers have no discernible resistance during the entire takeup, and only encounters resistance at the very end of takeup (often described as encountering "the wall") when actually actuating the trigger break.

- Two-stage triggers have a noticeable but relatively light resistance during the takeup, followed by a distinctly increased resistance of the actual trigger break. This allows the shooter to gradually "ease into" the trigger pull instead of hitting with a sudden hard squeeze.

A single-stage trigger is often called direct trigger, and is popular on hunting rifles. A two-stage trigger is often called pressure trigger, and is popular on competition rifles.

Some fully adjustable triggers can be adjusted to function as either a single-stage or two-stage trigger by adjusting the takeup. Setting the takeup travel (also known as the first stage) to near zero essentially makes the trigger a single-stage trigger. Some single-stage triggers (e.g. Glock trigger, Savage AccuTrigger) has an integral safety that can functionally mimic a two-stage trigger.

Break

The trigger break is named for the sudden loss of resistance when the sear reaches the point of release, which is described as resembling the breaking of rigid materials when the strength fails under stress. The actuation force required to overcome the sear resistance during the break is known as the trigger weight, which is usually measured in pounds with a force gauge.

The break is often considered the most critical stage of the trigger pull for achieving good practical accuracy, since it happens just prior to the shot being discharged and can cause some unwanted shakes from the shooter's hand at the instant of firing. Shooter preferences vary; some prefer a soft break with a smooth but discernible amount of trigger travel during firing, while others prefer a crisp break with a heavier weight and little or no discernible movement. A perceivably slow trigger break is often referred to as a "creep", and frequently described as an unfavorable feature.

Overtravel

The trigger overtravel happens immediately after the break and is typically very brief, and can be considered an inertially accelerated motion caused by the residual push of the finger coupled with the sudden decrease in resistance after the trigger break. It can be a very critical factor for accuracy because shaking movements during this phase may precede the projectile leaving the barrel, and is especially important with firearms with long barrels and heavy trigger weights, where the more significant resistance drop can make the trigger finger overshoot and shake in an uncontrolled fashion. Having some overtravel provides a "buffer zone" that prevents the shooter from "jerking the trigger", allowing the remnant pressing force from the finger to be dampened via a "follow-through" motion. Although a preceivable overtravel can be felt as adding to the "creep" of the trigger break, it is not always considered a bad thing by some shooters. An overtravel stop will arrest the motion of the trigger blade, and prevent excessive movement.

Types

There are numerous types of trigger designs, typically categorized according to which functions the trigger is tasked to perform, a.k.a. the trigger action (not to be confused with the action of the whole firearm, which refers to all the components that help handle the cartridge, including the magazine, bolt, hammer and firing pin/striker, extractor and ejector in addition to the trigger). While a trigger is primarily designed to set off a shot by releasing the hammer/striker, it may also perform additional functions such as cocking (i.e. loading against a spring) the hammer/striker, rotating a revolver's cylinder, deactivating internal safeties, transitioning between different firing modes (see progressive trigger), or reducing the pull weight (see set trigger).

Single-action

A single-action (SA) trigger is the earliest and mechanically simplest of trigger types. It is called the "single-action" because it performs the single function of releasing the hammer/striker (and nothing else), while the hammer/striker must be cocked by separate means.[1] Almost all single-shot and repeating long arms (rifles, shotguns, SMGs/machine guns etc.) use this type of trigger.[1]

The term "single-action" is a retronym that was not in use until weapons with double-action triggers were invented in the mid-19th century; before that, all triggers were single-action (for example, all matchlocks, flintlocks, muskets, etc.). While originally all hammers required a separate hand motion to cock manually, with the birth of repeating rifles such as the Henry rifle, it was found to be easy to design the cocking phase of the hammer into the cycling of the bolt. Although these weapons do not require the user to physically manipulate the hammer in addition to squeezing the trigger, they are still single-actions because the cocking is not performed by the trigger mechanism, which is only in charge of releasing the sear.

In modern usage, the terms "single-action" and "double-action" almost always refer to handguns, as few (if any) long guns feature double-action triggers. In handguns, genuinely single-action triggers with external hammers now are only seen on revolvers, while pretty much all semi-automatic pistols that support single-action firing are actually DA/SA hybrids, which is technically a two-stage double-action trigger with the cocking (first) stage being separately operable (hence can be "skipped" by the trigger). The longevity of purely single-action triggers on revolvers is mainly due to the gun's design layout — the revolver action relies on a rotating cylinder without using any reciprocating slide/bolt that can prohibit the shooter placing the fingers near the hammer for easy access, and it's not uncommon to see revolver shooters "fanning" the hammer to perform rapid single-action firing. While a "single-action" revolver or semi-automatic pistol must always be cocked prior to firing (either manually or by the operation of the weapon), most "double-action" handguns are capable of firing in both single- and double-action modes. Only "double-action only" weapons are incapable of firing from a cocked hammer.

The "classic" single-action revolver of the mid-to-late 19th century includes black powder caplock muzzleloaders such as the Colt 1860 "Army" Model, and Colt 1851 "Navy" Model, and European models like the LeMat, as well as early metallic cartridge revolvers such as the Colt Model 1873 "Single Action Army" (named for its trigger mechanism) and Smith & Wesson Model 3, all of which required a thumb to cock the hammer before firing. Single-action triggers with manually cocked external hammers lasted a while longer in some break-action shotguns and in dangerous game rifles, where the hunter did not want to rely on an unnecessarily complex or fragile weapon. While single-action revolvers never lost favor in the US right up until the birth of the semi-automatic pistol, double-action revolvers such as the Beaumont–Adams were designed in Europe before the American Civil War broke out, and saw great popularity all through the latter half of the 19th century, with certain numbers being sold in the US as well.

While many European and some American revolvers were designed as double-action models throughout the late 19th century, for the first half of the 20th century, all semi-automatic pistols were single-action weapons, requiring the weapon to be carried cocked and loaded with the safety on, or uncocked with an empty chamber (Colt M1911, Mauser C96, Luger P.08, Tokarev TT, Browning Hi-Power). The difference between these weapons and single-action revolvers is that while a single-action revolver requires the user to manually cock the hammer before each firing, a single-action semi-automatic pistol only requires manual cocking for the first shot, after which the slide will reciprocate under recoil to automatically recock the hammer for a next shot, and is thus always cocked and ready unless the user manually decocks the hammer, encounters a misfiring cartridge, or pulls the trigger on an empty chamber (for older weapons lacking "last round bolt hold open" feature).

In the late 1930s and early 1940s, Walther introduced the first "double-action" (actually DA/SA hybrid) semi-automatic pistols, the PPK and P.38 models, which featured a revolver-style double-action trigger, allowing the weapon to be carried with a round chambered and the hammer lowered. After the first shot, they would fire subsequent shots like as single-action pistol. These pistols rapidly gained popularity, and the traditional single-action-only pistols rapidly lost favor, although they still retain a dedicated following among enthusiasts. Today, a typical revolver or semi-automatic pistol is a DA/SA one, carried in double-action mode but firing most of its shots in single-action mode.

Double-action only

A double-action trigger, also known as double-action only (DAO) to prevent confusion with the more common hybrid DA/SA designs, is a trigger that must perform the double function of both cocking and releasing the hammer/striker. Such trigger design either has no internal sear mechanism capable of holding the hammer/striker in a still position (so cocking and releasing have to happen in one uninterrupted sequence), or has the whole hammer shrouded and/or with the thumb spur machined off, preventing the user from manipulating it separately.

This design requires a trigger pull to both cock and trip the hammer/striker for every single shot, unlike a DA/SA, which only requires a double-action trigger pull for the first shot (or a typical DA/SA revolver, which can fire single action any time the user wishes, but uses double-action as a default). This means that there is no single-action function for any shot, and the hammer or striker always rests in the down position until the trigger pull begins. With semi-automatics, this means that unlike DA/SA weapons, the hammer does not remain cocked after the first round is fired, and every shot is in double-action mode. With revolvers, this means that one does not have the option of cocking the gun before shooting, and must always shoot it in double action mode.

Although there have been revolvers that were designed with trigger mechanisms totally lacking a single-action mechanism altogether, more commonly DAO revolvers are modifications of existing DA/SA models, with identical internals, only with access to the hammer prevented, either by covering it with a shroud or by removing the thumb spur. In both cases, the goal is to prevent the possible snagging of the hammer spur on clothing or holster. Due to the imposed limitation in accuracy, the majority of DAO revolvers have been short-barrel, close-range "snub" weapons, where rapidity of draw is essential and limited accuracy is already an acceptable compromise.

The purpose of a DAO action in a semi-automatic is mostly to avoid the change in trigger pull between the first and subsequent shots that one experiences in a DA/SA pistol, while avoiding the perceived danger of carrying a cocked single-action handgun, although it also avoids having to carry a cocked and loaded pistol, or having to lower the hammer on a loaded chamber, if one only fires a partial magazine. A good example of this action in a semi-automatic is the SIG Sauer DAK trigger, or the DAO action of the Sig P250. For striker-fired pistols such as the Taurus 24/7, the striker will remain in the rest position through the entire reloading cycle. This term applies most often to semi-automatic handguns; however, the term can also apply to some revolvers such as the Smith & Wesson Centennial, the Type 26 Revolver, and the Enfield No. 2 Mk I revolvers, in which there is no external hammer spur, or which simply lack the internal sear mechanism capable of holding the hammer in the cocked position.

Double-action/single-action

A double-action/single-action (DA/SA) trigger is a hybrid design combining the features of both single- and double-action mechanisms. It is also known as traditional double-action (TDA), as vast majority of the modern "double-action" handguns (both revolvers and semi-automatic pistols) use such type of triggers instead of "double-action only" (DAO).

In simple terms, "double-action" refers to a trigger mechanism that both cocks the hammer and then releases the sear, thus performing two "acts", although it is supposed to describe doing both strictly with one trigger pull only. However, in practice most double-action guns feature the optional ability to cock the hammer separately, reducing the trigger to perform just one action. This is opposed to "double-action only" firearms, which completely lack the capability to fire in single-action mode.

In a DA/SA trigger, the mechanism is designed with an internal sear that allows the trigger to both cock and release the hammer/striker when fully pulled, or to merely lock the hammer/striker in the cocked position when it is pulled to the rear and the trigger is not depressed. In a revolver, this means that simply squeezing the trigger when the hammer is lowered will both cock and release it. If the user uses their thumb to pull the hammer to the back, but doesn't press the trigger, the mechanism will lock the hammer in the cocked position until the trigger is pressed, just like a single action. Firing in double-action mode allows a quicker initiation of fire, but compromised by having a longer, heavier trigger pull, which can affect accuracy compared to the lighter, shorter trigger pull of a single-action fire.

In a DA/SA semi-automatic pistol, the trigger mechanism functions identically to that of a DA revolver. However, this is combined with the ability of the pistol slide to automatically cock the hammer when firing. Thus, the weapon can be carried with the hammer down on a loaded chamber, reducing perceived danger of carrying a single-action semi-automatic. When the user is ready to fire, simply pulling the trigger will cock and release the hammer in double action mode. When the weapon fires, the cycling slide automatically cocks the hammer to the rear, meaning that the rest of the shots fired will be in single-action mode, unless the hammer is manually lowered again. This gives the positive aspects of a single-action trigger without the need to carry "cocked and locked" (with a loaded chamber and cocked hammer), or with an empty chamber, which requires the user to chamber a round before firing.

A potential drawback of a DA/SA weapon is that the shooter must be comfortable dealing with two different trigger pulls: the longer, heavier DA first pull and the shorter, lighter subsequent SA pulls. The difference between these trigger pulls can affect the accuracy of the crucial first few shots in an emergency situation. Although there is little need for a safety on a DA/SA handgun when carrying it loaded with the hammer down, after the first shots are fired, the hammer will be cocked and the chamber loaded. Thus, most DA/SA guns either feature a conventional safety that prevents the hammer from accidentally dropping, or a "decocker" — a lever that safely and gently drops the hammer (i.e. decocks the gun) without fear of the gun firing. The latter is the more popular because, without a decocker, the user is forced to lower the hammer by hand onto a loaded chamber, with all of the attendant safety risks that involves, in order to return the gun to double-action mode. Revolvers almost never feature safeties, since they are traditionally carried un-cocked, and the hammer requires the user to physically cock it prior to every shot; unlike a DA/SA gun, which cocks itself every time the slide is cycled.

There are many examples of DA/SA semi-automatics, the Little Tom Pistol being the first,[2][3] followed up by the Walther PPK and Walther P38. Modern examples include weapons such as the Beretta 92, among others. Almost all revolvers that are not specified as single-action models are capable of firing in both double- and single-action mode, for example, the Smith & Wesson Model 27, S&W Model 60, the Colt Police Positive, Colt Python, etc. Early double-action revolvers included the Beaumont–Adams and Tranter black-powder muzzleloaders. There are some revolvers that can only be fired in double-action mode (DAO), but that is almost always due to existing double-action/single-action models being modified so that the hammer cannot be cocked manually, rather than from weapons designed that way from the factory.

Release trigger

A release trigger releases the hammer or striker when the trigger is released by the shooter, rather than when it is pulled.[4] Release triggers are largely used on shotguns intended for trap and skeet shooting.

Binary triggers ("pull and release")

A binary trigger is a trigger for a semiautomatic firearm that drops the hammer both when the trigger is pulled, and also when it is released. Examples include the AR-15 series of rifles, produced by Franklin Armory, Fostech Outdoors, and Liberty Gun Works. The AR-15 trigger as produced by Liberty Gun Works only functions in pull and release mode, and does not have a way to catch the hammer on release; while the other two have three-position safety selectors and a way to capture the hammer on release. In these triggers, the third position activates the pull and release mode, while the center selector position causes the trigger to only drop the hammer when pulled.

Set trigger

A set trigger allows a shooter to have a greatly reduced trigger pull (the resistance of the trigger) while maintaining a degree of safety in the field compared to having a conventional, very light trigger. There are two types: single set and double set. Set triggers are most likely to be seen on customized weapons and competition rifles where a light trigger pull is beneficial to accuracy.

Single set trigger

A single set trigger is usually one trigger that may be fired with a conventional amount of trigger pull weight or may be "set"—usually by pushing forward on the trigger, or by pushing forward on a small lever attached to the rear of the trigger. This takes up the trigger slack (or "take-up") in the trigger and allows for a much lighter trigger pull. This is colloquially known as a hair trigger.

Double set trigger

A double set trigger achieves the same result, but uses two triggers: one sets the trigger and the other fires the weapon. Double set triggers can be further classified by phase.[5] A double set, single phase trigger can only be operated by first pulling the set trigger, and then pulling the firing trigger. A double set, double phase trigger can be operated as a standard trigger if the set trigger is not pulled, or as a set trigger by first pulling the set trigger. Double set, double phase triggers offer the versatility of both a standard trigger and a set trigger.

Pre-set (striker or hammer)

Pre-set strikers and hammers apply only to semi-automatic handguns. Upon firing a cartridge or loading the chamber, the hammer or striker will rest in a partially cocked position. The trigger serves the function of completing the cocking cycle and then releasing the striker or hammer. While technically two actions, it differs from a double-action trigger in that the trigger is not capable of fully cocking the striker or hammer. It differs from single-action in that if the striker or hammer were to release, it would generally not be capable of igniting the primer. Examples of pre-set strikers are the Glock, Smith & Wesson M&P, Springfield Armory XD-S variant (only), Kahr Arms, FN FNS series and Ruger SR series pistols. This type of trigger mechanism is sometimes referred to as a Striker Fired Action or SFA. Examples of pre-set hammers are the Kel-Tec P-32 and Ruger LCP pistols.

Pre-set hybrid

Pre-set hybrid triggers are similar to a DA/SA trigger in reverse. The first pull of the trigger is pre-set. If the striker or hammer fail to discharge the cartridge, the trigger may be pulled again and will operate as a double-action only (DAO) until the cartridge discharges or the malfunction is cleared. This allows the operator to attempt a second time to fire a cartridge after a misfire malfunction, as opposed to a single-action, in which the only thing to do if a round fails to fire is to rack the slide, clearing the round and recocking the hammer. While this can be advantageous in that many rounds will fire on being struck a second time, and it is faster to pull the trigger a second time than to cycle the action, if the round fails to fire on the second strike, the user will be forced to clear the round anyway, thus using up even more time than if they had simply done so in the first place. The Taurus PT 24/7 Pro pistol (not to be confused with the first-generation 24/7 which was a traditional pre-set) offered this feature starting in 2006. The Walther P99 Anti-Stress is another example.

Double-crescent trigger

A double-crescent trigger provides select fire capability without the need for a fire mode selector switch. Pressing the upper segment of the trigger produced semi-automatic fire, while holding the lower segment of the trigger produced fully automatic fire. Though considered innovative at the time, the feature was eliminated on most firearms due to its complexity. Examples include MG 34, Kg m/40 light machine gun, M1946 Sieg automatic rifle, and Star Model Z-70.

Progressive/staged trigger

A progressive, or staged trigger allows different firing rates based on how far it is depressed. For example, when pulled lightly, the weapon will fire a single shot. When depressed further, the weapon fires at a fully automatic rate.[6] Examples include FN P90, Jatimatic, CZ Model 25, PM-63, BXP, F1 submachine gun, Vigneron submachine gun, Wimmersperg Spz-kr, and Steyr AUG.

Relative merits

Each trigger mechanism has its own merits. Historically, the first type of trigger was the single-action.[7] This is the simplest mechanism and generally the shortest, lightest, and smoothest pull available.[7] The pull is also consistent from shot to shot so no adjustments in technique are needed for proper accuracy. On a single-action revolver, for which the hammer must be manually cocked prior to firing, an added level of safety is present. On a semi-automatic, the hammer will be cocked and made ready to fire by the process of chambering a round, and as a result an external safety is sometimes employed.

Double-action triggers provide the ability to fire the gun whether the hammer is cocked or uncocked. This feature is desirable for military, police, or self-defense pistols. The primary disadvantage of any double-action trigger is the extra length the trigger must be pulled and the extra weight required to overcome the spring tension of the hammer or striker.

DA/SA pistols are versatile mechanisms. These firearms generally have a manual safety that additionally may serve to decock the hammer. Some have a facility (generally a lever or button) to safely lower the hammer. As a disadvantage, these controls are often intermingled with other controls such as slide releases, magazine releases, take-down levers, takedown lever lock buttons, loaded chamber indicators, barrel tip-up levers, etc. These variables become confusing and require more complicated manuals-of-arms. One other disadvantage is the difference between the first double-action pull and subsequent single-action pulls.

DAO firearms resolve some DA/SA shortcomings by making every shot a double-action shot. Because there is no difference in pull weights, training and practice are simplified. Additionally, the heavier trigger pull can help to prevent a negligent discharge under stress.[8] This is a particular advantage for a police pistol. These weapons also generally lack any type of external safety. DAO is common among police agencies and for small, personal protection firearms. The primary drawback is that additional trigger pull weight and travel required for each shot reduce accuracy.

Pre-set triggers, only recently coming into vogue, offer a balance of pull weight, trigger travel, safety, and consistency. Glock popularized this trigger in modern pistols and many other manufacturers have released pre-set striker products of their own. The primary disadvantage is that pulling the trigger a second time after a failure to fire will not re-strike the primer. In normal handling of the firearm, this is not an issue; loading the gun requires that the slide be retracted, pre-setting the striker. Clearing a malfunction also usually involves retracting the slide following the "tap rack bang" procedure. Many similar approaches are argued for generally accomplishing the same end.

References

- "Trigger Analysis". Ballistics-Experts.com. Archived from the original on February 11, 2003.

- https://www.forgottenweapons.com/ria-little-tom-the-worlds-first-dao-automatic/

- https://www.thefirearmblog.com/blog/2016/06/03/little-tom-pistol-first-dasa-ever-made/

- U.S. Patent 2,027,950

- "Trigger Function and Terminology". Spencer, B. E. Archived from the original on 2011-07-20.

- "Trigger mechanism providing a short burst of fire capability for submachine guns". freepatentsonline.com.

- "Trigger Options of the Semi-Automatic Service Pistol". Chuckhawks.com. Archived from the original on 2014-11-08.

- "Choosing A Carry Pistol – Part V – The Double Action Only (DAO) Pistol". Velocity Works. July 1, 2019. Retrieved March 13, 2020.