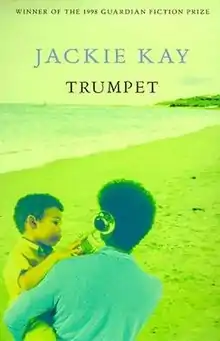

Trumpet (novel)

Trumpet is the debut novel of Scottish writer and poet Jackie Kay, published in 1998. It chronicles the life and death of fictional jazz artist Joss Moody through the recollection of his family and friends and those who came in contact with him at his death. Kay stated in an interview that her novel was inspired by the life of Billy Tipton, an American jazz musician who lived with the secret of being transgender.

Hardback edition | |

| Author | Jackie Kay |

|---|---|

| Audio read by | Cathleen McCarron |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Novel |

| Publisher | Picador (UK) |

Publication date | 1998 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| Pages | 278 pp |

| ISBN | 0-330-33145-0 |

| OCLC | 40119161 |

Plot

The novel begins just after the main character, Joss Moody, a famous jazz trumpeter, passes away. After his death, there is a revelation that his biological sex was female, causing a news rush and attracting paparazzi, leading his widow, Millie, to flee to a vacation home. The truth was unknown to anyone except Millie; the Moodys lived their life as a normal married couple with a normal house and a normal family, and not even Colman, their adopted son, knew the truth. When Joss dies and the truth is revealed, Colman's shock spills into bitterness and he seeks revenge. He vents his rage of his father's lie by uncovering Joss's life to Sophie, an eager tabloid journalist craving to write the next bestseller. After time, and a visit to Joss's mother Edith Moore, Colman eventually finds love for his father muddled in his rage. With his new-found acceptance of both his father and himself, Colman makes the decision not to follow through with the book deal. All the while, Millie deals with her grief and the scandal in private turmoil at the Moodys' vacation home, and a variety of characters whose paths have crossed with Joss's give accounts of their memories and experiences. All the characters aside from Sophie seem to either accept Joss's identity or to perceive it as irrelevant.

Setting and narrative voice

Trumpet is mostly set in London in 1997. Memories of Joss's lifetime give the book's setting a 70-year time-span beginning in 1927. A majority of these memories are set in Glasgow in the 1960s, referring to locations such as The Barrowlands music venue, during the beginning of Joss and Millie's relationship and their early marriage. Although much of the story takes place in London where the Moodys lived, it jumps back and forth between the city and the Scottish seaside home to which Millie goes to escape the scandal and grieve in peace. The end of the novel is entirely set in Scotland, where Colman and Sophie go to investigate the place of Joss's birth.

Trumpet is written with an intricate narration, incorporating many characters' point of view. The narration varies by chapter. Most of the story is told from the first-person perspective of Joss's wife Millie, his son Colman, and the journalist Sophie Stones. The narration often takes the form of the inner thoughts of these three characters, including visitations of their memories. Some chapters are Colman responding to Sophie Stones' interview. In addition, chapters told from a third-person omniscient narrator contribute to the story, each focusing on a different minor character, such as the funeral director or Joss's drummer.

Characters

- The central character is Joss Moody, a famous black jazz musician. The novel begins in the wake of his death. Assigned female at birth and named Josephine Moore, Joss is transgender. He becomes a famous trumpet player and devotes his life to his passion of music. Joss is portrayed as a passionate lover, strict father, energetic friend, and dedicated artist.

- Millie Moody, a white woman, is married to Joss. As a young adult, she falls in love with Joss, and her passion is strong enough to overcome the truth about his original gender. After his death, Millie is devastated. Although she outwardly handles herself with grace and composure, Millie's heart is broken. Millie is a loving, sympathetic character living out the cycles of grief under an unwanted spotlight.

- Colman Moody is the adopted son of Millie and Joss. He is of mixed race. As a child, Colman was often difficult and misbehaved. Upon his father's death, Colman, aged 30, discovers that his father was assigned female at birth, and experiences a range of emotions including confusion, anger, embarrassment, and grief, which drives him to cooperate with a journalist, Sophie Stones, in her attempt to write Joss Moody's story.

- Edith Moore is Joss Moody's mother. She enters the novel only at the end. We see her as she is growing old in a retirement home, and she has no knowledge that Joss had been living as male.

- Sophie Stones is a journalist who seeks to write a novel about the revelation of Joss Moody's identity, seeing it as a lucrative opportunity for her career. She expresses more overtly prejudiced and transphobic views regarding Joss's identity than others in the novel.

Themes

Identity

This sole element may be divided in three main subcategories: gender identity, cultural identity and racial identity. They are all developed under the main “umbrella-term” of identity, but genuinely also developed in their own specificity during the narration.The underlying theme of the novel is identity.[1] It explores many dualities such as male/female, black/white, famous/non-famous. Joss's experienced are shaped by his transgender identity, as well as his identity as a black Scottish man. Colman also grapples with not only his black and Scottish identities, but also his complex self-identity due to being adopted. The theme of identity is particularly explored through the novel's focus on names, and the changing of names, as an integral part of one's identity.

- Gender identity: the unravelling of these categories is one of the most highlighted themes in the novel, meaning that it is the first necessary step to develop and build an identity for many of the characters. It does apply to Joss of course, but also to the other characters such as Millie (she never thinks that she is lesbian since she always sees Joss as a trans man, whereas society and other characters don’t). After what appears to be a fight for the right to not conform to gender assigned roles, after the death of Joss, he is forced back into a categorised role delegated by a binary and heteronormative society.[2]

- Cultural identity: the principal location of the novel is set in Scotland in the middle of the XX century. With the storyline spanning from 1927 till 1997, a period of time that saw a lot of change. Scotland is presented as fundamentally traditional, orthodox, conservative country, where the question of identity is not even asked.[3] Many references to the patriarchal culture are seen throughout the narration, as well as with the actions of the characters (the improper use of the “she/her” pronouns by the journalist when referring to Joss; Colman’s sex desire in order to maintain, or define, his own masculinity, virility and manhood).

- Race identity: Race is also an important component in the identity of the characters. Joss is a black man, son of the Scottish nation, but lives in a country which hardly recognizes his social status as minority.[4] An interesting parallel is with the author, Jackie Kay who also grew up in Scotland, and she was Scottish through her mother and Nigerian through her father. Her life and the one of the main characters (Joss) are both of a mixture of backgrounds and many similarities can emerge between the two personalities. Living in Scotland she belonged to a true minority group of British blacks, since according to National Statistics publication for Scotland, only 1% of the Scottish population belongs to the African, Caribbean or Black ethnic groups.[5]

The “manhood” question in Colman

Colman is mad at Joss because his father had a female body. In Colman’s view, Joss is not following the gender roles imposed by the patriarchal society, that he (Colman) conforms to (see for example the scene where Colman wants to have anal sex with the journalist to impose his control on her, as expression of the culture of possession, a crucial element in a patriarchal system). It is almost ironic that Colman is marginalizing his father even if he knows how it feels to be marginalized, especially in a European context where being a black man can be difficult. Colman feels that his identity as a man is being questioned after his father’s death because he loses a sense of attachment to the safety and assurance from the patriarchal culture and system. In a sense we can see Colman categorizing people in the same manner that he gets marginalized by others.[6]

Sex

One can read how sex is depicted in the novel in two different ways: the first one is between Millie and Joss, which is described in the very first pages of the book where we know that Joss was assigned female body to birth. It is a genuine, lovely, naive relationship. The second one is the form of sex used by Colman as a form of revenge. The relationship Colman has with sex is certainly due to a trauma when he finds out that his father had female genitalia, but may also be linked to the possessive nature of the patriarchal system.

Music, role of jazz and the trumpet

Jazz music and in general the role of the music in black culture is a form of expression through which Joss expresses his identity through his undeniable ability to play music. Music comes to be a liberating practice.[7] Every single character seems to be an instrument and part of a musical narration where the union of the characters becomes an orchestra.The role of Jazz in this novel shows a sharp contrast to other dominant themes. With a strong duality of themes, notably male and female, black and white, jazz on the other hand, offers a freedom and detachment from social norms and constrictions. With Joss being able to find comfort in his music, and of course the symbolic fact that he played the trumpet (which has a phallic shape)[8] music in this novel plays a vital role in liberating the characters from the social norms of society. It is the one consistent theme throughout the novel which does not change, even when Joss’s sex is revealed, the love of jazz remains, so much so that his friend and partner Big Red, defends him even after his death. He builds his public identity through music and with an instrument which (casually or not) reminds him of the organ he doesn’t have. Joss found his masculinity in jazz music, whereas Colman identifies his masculinity in his physique.[9]

Transphobia

We are not apparently allowed to see Millie’s reaction when she discovers that Joss has the body of a woman in their first intimate encounter; we do, she gets angry and then does not mind. But interestingly, it is never mentioned again, the only remarks of transphobia that we find are from people who weren’t privately linked to Joss (except for this son of course).Through the narrations, we can only see people’s reaction to the discovery after Joss’ death, manifested through a sense of disorientation, disgust or just general transphobia. Miss Stones is the peak of this process, since she refuses to use the “him/his” pronouns from the first time she talks about Joss, denying him the legitimate recognition of his identity.[9] Transphobia then is not only addressed to Joss, but also to all the people he knew, starting with his family and friends, disregarding their opinion of him, making it all the more difficult for him to be defended when he is not there to do it himself.[8]

Passing

From the novel emerges a general perception that death is a moment that makes someone more vulnerable and exposed to the critiques from which he cannot defend himself. Private life becomes public.[9] Joss’ identity is discussed and questioned, his body is accurately analyzed, and he can’t defend himself. The only attempt to defend Joss’ is made by his wife Millie, but at the end it appears weak, blurred and almost inconsistent. After his death he is treated as “a black queer monstrosity that can be met only with derision and turned into spectacle” [6] and the only thing Millie continues to do is referring to him using the male pronouns.

Family relationships

Another theme in the novel is familial relationships, especially the relationship between Joss and Colman. After his father's death, Colman reflects on his childhood and how his relationship with his dad has changed over time. His relationship with his father had tension due to the fact that Colman wasn't as successful as his father. Their relationship is noticeably difficult starting from Colman’s adolescence, the moment in his life when he starts developing the typical secondary characteristics and the body becomes physically “masculine”. This tension increased upon Joss’s death and Colman discovering that his father was a trans man. At a certain point in the book, coinciding with Colman’s narration of a conspicuous part of his adolescence, Joss starts to develop a sort of envy for Colman’s body, probably seeing in him attributes that he does not possess (it is important anyway to note that the narration in this part follows just Colman's point of view). The novel ends with Colman reading a letter his dad left for him, which talks about his own father.

Race and gender

The novel also explores issues around race and gender. Both Joss and Colman give insight into the experiences of black people in Britain and Scotland, and the prejudices they experience. For instance, Millie's mother initially objects to their marriage on account of Joss's race. Joss not only had to learn how to navigate the world as a biracial Black person, but also as a transgender man. He had to learn how to pass as a man, and went to great lengths to ensure that no one found out he was trans beside Millie. The novel also explores the fluidity of gender perception, as characters frequently describe Joss's face transforming, becoming more feminine upon learning his identity as transgender, despite previously perceiving him wholly as male.

Public vs. Private

The novel explores issues of fame and the invasion of privacy through the media, resulting in the private life turning "horribly public".[1] This clash is illustrated through the paparazzi and media who exploit Millie's grief, forcing her to flee from her home. Colman's interviews with Sophie turn private memories public, and the novel's chapters are titled in the style of media headings and newspaper sections, mirroring the invasion of Joss's privacy and identity for public attention.

Reception

In an interview, Kay spoke about her desire to make her story read like music, specifically echoing the structure of jazz music.[10] Critics have acclaimed her for accomplishing this goal in a powerful and intricate narrative without melodrama. In an article for the Boston Phoenix, David Valdes Greenwood wrote that "in the hands of a less graceful writer, Jackie Kay's Trumpet would have been a polemic about gender with a dollop of race thrown in for good measure. But Kay has taken the most tabloid topic possible and produced something at once more surprising and more subtle: a rumination on the nature of love and the endurance of a family".[11] Time magazine called it a "hypnotic story ... about the walls between what is known and what is secret. Spare, haunting, dreamlike", and the San Francisco Chronicle commented that "Kay's imaginative leaps in story and language will remind some readers of a masterful jazz solo".

Matt Richardson, in his analysis of the transgender subjectivity and the use of a Jazz aesthetic in the novel, noted that "as a form that encourages the transformation of standard melodies into multiple improvised creations, jazz is useful in expanding our conceptualization of the potential for black people to recreate ourselves and our gender identities in a diasporic practice".[12]

Awards and nominations

Trumpet was awarded the Guardian Fiction Prize in 1998 and the Authors' Club First Novel Award in 2000, and won in the Transgender category at the 2000 Lambda Literary Awards. It was shortlisted for the International Dublin Literary Award, also in 2000.

Adaptations

Kay served as advisor to Grace Barnes, director of Skeklers Theatre Company, in her stage adaptation of Trumpet. The stage version was performed in the Citizens Theatre in Glasgow in 2005.

Publication history

Copyright 1998 by Jackie Kay, Trumpet was originally published by Picador (Great Britain) in 1998, and Pantheon Books (New York). It was published by Vintage Books, a Division of Random House, Inc. (New York), in 2000.

Bibliography

- Trumpet: A Novel. Random House Digital, Inc. 2011. ISBN 978-0-307-56081-0.

References

- Richardson, M. ""My Father Didn't Have a Dick": Social Death and Jackie Kay's Trumpet". GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies. 18 (2–3): 366. ISSN 1064-2684.

- Richardson, M. ""My Father Didn't Have a Dick": Social Death and Jackie Kay's Trumpet". GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies. 18 (2–3): 364. ISSN 1064-2684.

- Richardson, M. ""My Father Didn't Have a Dick": Social Death and Jackie Kay's Trumpet". GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies. 18 (2–3): 369. ISSN 1064-2684.

- "Author Index". Calcutta Statistical Association Bulletin. 65 (1–4): 241–244. March 2013. doi:10.1177/0008068320130115. ISSN 0008-0683. S2CID 220748525.

- Richardson, M. ""My Father Didn't Have a Dick": Social Death and Jackie Kay's Trumpet". GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies. 18 (2–3): 367. ISSN 1064-2684.

- Kähkönen, Lotta (2013). "Reading the Potential of Jackie Kay's Trumpet for Transgender Ethics". Lambda Nordica (in Swedish). 18 (3–4): 123–143. ISSN 2001-7286.

- Koolen, Mandy (1 January 2010). "Masculine Trans-formations in Jackie Kay's Trumpet". Atlantis: Critical Studies in Gender, Culture & Social Justice. 35 (1): 71–80. ISSN 1715-0698.

- "Ali Smith on Trumpet by Jackie Kay: a jazzy call to action". the Guardian. 16 January 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- Interview with Jackie Kay.

- Richardson, Matt. The Queer Limit of Black Memory: Black Lesbian Literature and Irresolution (Black Performance and Cultural Criticism). Ohio State University Press: 2013. Page 108