Turkish makam

The Turkish makam (Turkish: makam pl. makamlar; from the Arabic word مقام) is a system of melody types used in Turkish classical music and Turkish folk music. It provides a complex set of rules for composing and performance. Each makam specifies a unique intervalic structure (cinsler meaning genera) and melodic development (seyir).[1] Whether a fixed composition (beste, şarkı, peşrev, âyin, etc.) or a spontaneous composition (gazel, taksim, recitation of Kuran-ı Kerim, Mevlid, etc.), all attempt to follow the melody type. The rhythmic counterpart of makam in Turkish music is usul.

Comparison in use in Turkish classical to folk music

Turkish Classical Music and Turkish Folk Music are both based on modal systems. Makam is the name of the scale in classical music, while Ayak is the name of the scale in folk music. Makam and Ayak are similar; following are some examples:

Yahyalı Kerem Ayağı : Hüseyni Makamı

Garip Ayağı : Hicaz Makamı

Düz Kerem Ayağı : Karciğar Makamı

Yanık Kerem Ayağı : Nikriz Makamı

Muhalif Ayağı : Segâh Makamı

Tatyan Kerem Ayağı : Hüzzam Makamı

Misket Ayağı : Eviç Makamı

Bozlak Ayağı : Kürdî Makamı

Kalenderi Ayağı : Sabâ Makamı

Müstezat veya Beşirî Ayağı : Mahur Makamı

Rhythms show some similarities in Turkish Folk Music and Turkish Classical Music with respect to their forms, classification and rhythmic patterns.[2]

Geographic and cultural relations

The Turkish makam system has some corresponding relationships to maqams in Arabic music and echos in Byzantine music. Each of these systems were derived from ancient Greek texts and musical works, translated and developed by Arabs from the musical theory of the Greeks (i.e. Systema ametabolon, enharmonium, chromatikon, diatonon).[3] Some theories suggest the origin of the makam to be the city of Mosul in Iraq. "Mula Othman Al-Musili," in reference to his city of origin, is said to have served in the Ottoman Palace in Istanbul and influenced Turkish Ottoman music. More distant modal relatives include those of Central Asian Turkic musics such as Uyghur “muqam” and Uzbek shashmakom. North and South Indian classical raga-based music employs similar modal principles. Some scholars find echoes of Turkish makam in former Ottoman provinces of the Balkans.[4] All of these concepts roughly correspond to mode in Western music, although their compositional rules vary.

Makam building blocks

Commas and accidentals

In Turkish music theory, the octave is divided into 53 equal intervals known as commas (koma), specifically the Holdrian comma. Each whole tone is an interval equivalent to nine commas. The following figure gives the comma values of Turkish accidentals. In the context of the Arab maqam, this system is not of equal temperament. In fact, in the Western system of temperament, C-sharp and D-flat—which are functionally the same tone—are equivalent to 4.5 commas in the Turkish system; thus, they fall directly in the center of the line depicted above.

Notes

Unlike in Western music, where the note C, for example, is called C regardless of what octave it might be in, in the Turkish system the notes are—for the most part—individually named (although many are variations on a basic name); this can be seen in the following table, which covers the notes from middle C ("Kaba Çârgâh") to the same note two octaves above ("Tîz Çârgâh"):

.jpg.webp)

The following table gives the tones over two octaves (ordered from highest to lowest), the pitch in commas and cents relative to the lowest note (which is equivalent to Western Middle C), along with the nearest equivalent equal-temperament tone. The tones of the çârgâh scale are shown in upper case.

| Tone Name | Commas above middle C |

Cents above middle C |

Arel-Ezgi-Uzdilek notation of 53-ΤΕΤ Tone |

Nearest Equiv 12-ΤΕΤ Tone |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TÎZ ÇÂRGÂH | 106 | 2400 | C6 | C6 |

| Tîz Dik Bûselik | 105 | 2377 | C | C6 |

| TÎZ BÛSELIK | 102 | 2309 | B5 | B5 |

| Tîz Segâh | 101 | 2287 | A | B5 |

| Dik Sünbüle | 98 | 2219 | A | A#5 / Bb5 |

| Sünbüle | 97 | 2196 | A♯5 / B♭5 | A#5 / Bb5 |

| MUHAYYER | 93 | 2106 | A5 | A5 |

| Dik Şehnâz | 92 | 2083 | G | A5 |

| Şehnâz | 89 | 2015 | G | G#5 / Ab5 |

| Nim Şehnâz | 88 | 1992 | G♯5 / A♭5 | G#5 / Ab5 |

| GERDÂNIYE | 84 | 1902 | G5 | G5 |

| Dik Mâhûr | 83 | 1879 | F | G5 |

| Mâhûr | 80 | 1811 | F | F♯5 / G♭5 |

| Eviç | 79 | 1789 | F♯5 / G♭5 | F♯5 / G♭5 |

| Dik Acem | 76 | 1721 | F | F5 |

| ACEM | 75 | 1698 | F5 | F5 |

| HÜSEYNÎ | 71 | 1608 | E5 | E5 |

| Dik Hisâr | 70 | 1585 | D | E5 |

| Hisâr | 67 | 1517 | D | D#5 / Eb5 |

| Nim Hisâr | 66 | 1494 | D♯5 / E♭5 | D#5 / Eb5 |

| NEVÂ | 62 | 1404 | D5 | D5 |

| Dik Hicâz | 61 | 1381 | C | D5 |

| Hicâz | 58 | 1313 | C | C#5 / Db5 |

| Nim Hicâz | 57 | 1291 | C♯5 / D♭5 | C#5 / Db5 |

| ÇÂRGÂH | 53 | 1200 | C5 | C5 |

| Dik Bûselik | 52 | 1177 | C | C5 |

| BÛSELIK | 49 | 1109 | B4 | B4 |

| Segâh | 48 | 1087 | A | B4 |

| Dik Kürdi | 45 | 1019 | A | A#4 / Bb4 |

| Kürdi | 44 | 996 | A♯4 / B♭4 | A#4 / Bb4 |

| DÜGÂH | 40 | 906 | A4 | A4 |

| Dik Zirgüle | 39 | 883 | G | A4 |

| Zirgüle | 36 | 815 | G | G#4 / Ab4 |

| Nim Zirgüle | 35 | 792 | G♯4 / A♭4 | G#4 / Ab4 |

| RAST | 31 | 702 | G4 | G4 |

| Dik Gevest | 30 | 679 | F | G4 |

| Gevest | 27 | 611 | F | F#4 / Gb4 |

| Irak | 26 | 589 | F♯4 / G♭4 | F#4 / Gb4 |

| Dik Acem Aşîrân | 23 | 521 | F | F4 |

| ACEM AŞÎRÂN | 22 | 498 | F4 | F4 |

| HÜSEYNÎ AŞÎRÂN | 18 | 408 | E4 | E4 |

| Kaba Dik Hisâr | 17 | 385 | D | E4 |

| Kaba Hisâr | 14 | 317 | D | D#4 / Eb4 |

| Kaba Nim Hisâr | 13 | 294 | D♯4 / E♭4 | D#4 / Eb4 |

| YEGÂH | 9 | 204 | D4 | D4 |

| Kaba Dik Hicâz | 8 | 181 | C | D4 |

| Kaba Hicâz | 5 | 113 | C | C#4 / Db4 |

| Kaba Nim Hicâz | 4 | 91 | C♯4 / D♭4 | C#4 / Db4 |

| KABA ÇÂRGÂH | 0 | 0 | C4 | C4 |

Intervals

The names and symbols of the different intervals are shown in the following table:

| Interval Name (Aralığın adı) |

Value in terms of commas (Koma olarak değeri) |

Symbol (Simge) |

|---|---|---|

| koma or fazla | 1 | F |

| eksik bakiye | 3 | E |

| bakiye | 4 | B |

| kücük mücenneb | 5 | S |

| büyük mücenneb | 8 | K |

| tanîni | 9 | T |

| artık ikili | 12 - 13 | A |

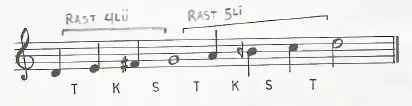

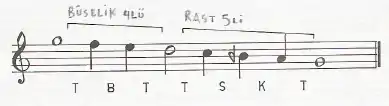

Tetrachords (dörtlüler) and pentachords (beşliler)

Similar to the construction of maqamat noted above, a makam in Turkish music is built of a tetrachord built atop a pentachord, or vice versa (trichords exist but are little used). Additionally, most makams have what is known as a "development" (genişleme in Turkish), which can occur either above or below (or both) the tonic and/or the highest note.

There are 6 basic tetrachords, named sometimes according to their tonic note and sometimes according to the tetrachord's most distinctive note:

- Çârgâh

- Bûselik

- Kürdî

- Uşşâk

- Hicaz and

- Rast

There are also 6 basic pentachords with the same names with a tone (T) appended.

It is worth keeping in mind that these patterns can be transposed to any note in the scale, so that the tonic A (Dügâh) of the Hicaz tetrachord, for example, can be moved up a major second (9 commas) to B (Bûselik), or in fact to any other note. The other notes of the tetrachord, of course, are also transposed along with the tonic, allowing the pattern to preserve its character.

Basic makam theory

A makam, more than simply a selection of notes and intervals, is essentially a guide to compositional structure: any composition in a given makam will move through the notes of that makam in a more or less ordered way. This pattern is known in Turkish as seyir (meaning basically, "route"), and there are three types of seyir:

- rising (çıkıcı);

- falling (inici);

- falling-rising (inici-çıkıcı)

As stated above, makams are built of a tetrachord plus a pentachord (or vice versa), and in terms of this construction, there are three important notes in the makam:

- the durak ("tonic"), which is the initial note of the first tetrachord or pentachord and which always concludes any piece written in the makam;

- the güçlü ("dominant"), which is the first note of the second tetrachord or pentachord, and which is used as a temporary tonic in the middle of a piece (in this sense, it is somewhat similar to the axial pitches mentioned above in the context of Arab music). This use of the term "dominant" is not to be confused with the Western dominant; while the güçlü is often the fifth scale degree, it can just as often be the fourth, and occasionally the third;

- the yeden ("leading tone"), which is most often the penultimate note of any piece and which resolves into the tonic; this is sometimes an actual Western leading tone and sometimes a Western subtonic.

Additionally, there are three types of makam as a whole:

- simple makams (basit makamlar), almost all of which have a rising seyir;

- transposed makams (göçürülmüş makamlar), which as the name implies are the simple makams transposed to a different tonic;

- compound makams (bileşik/mürekkep makamlar), which are a joining of differing makams and number in the hundreds

Simple makams

Çârgâh makam

This makam is thought to be identical to the Western C-major scale, but actually it is misleading to conceptualize a makam through Western music scales. Çârgâh makam consists of a çârgâh pentachord and a çârgâh tetrachord starting on the note gerdâniye (G). Thus, the tonic is C (note çârgâh), the dominant is G (note gerdâniye), and the leading tone is B (note bûselik).

The çârgâh makam though is very little used in Turkish music, and in fact has at certain points of history been attacked for being a clumsy and unpleasant makam that can inspire those hearing it to engage in delinquency of various kinds.

Bûselik makam

This makam has two basic forms: in the first basic form (1), it consists of a Bûselik pentachord plus a Kürdî tetrachord on the note Hüseynî (E) and is essentially the same as the Western A-minor; in the second (2), it consists of a Bûselik pentachord plus a Hicaz tetrachord on Hüseynî and is identical to A-harmonic minor. The tonic is A (Dügâh), the dominant Hüseynî (E), and the leading tone G-sharp (Nim Zirgüle). Additionally, when descending from the octave towards the tonic, the sixth (F, Acem) is sometimes sharpened to become F-sharp (Dik Acem), and the dominant (E, Hüseynî) flattened four commas to the note Hisar (1A). All these alternatives are shown below:

1)

2)

1A)

Rast makam

- Also see the related maqam in Arabo-Persian music Rast (maqam)

This much-used makam—which is said to bring happiness and tranquility to the hearer—consists of a Rast pentachord plus a Rast tetrachord on the note Neva (D); this is labeled (1) below. The tonic is G (Rast), the dominant D (Neva), and the leading tone F-sharp (Irak). However, when descending from the octave towards the tonic, the leading tone is always flattened 4 commas to the note Acem (F), and thus a Bûselik tetrachord replaces the Rast tetrachord; this is labeled (2) below. Additionally, there is a development (genişleme) in the makam's lower register, below the tonic, which consists of a Rast tetrachord on the note D (Yegâh); this is labeled (1A) below.

1)

1A)

2)

In Turkey, the particular Muslim call to prayer (or ezan in Turkish) which occurs generally in early afternoon and is called ikindi, as well as the day's final call to prayer called yatsı, is often recited using the Rast makam.

Uşşâk makam

- Also see Bayati (maqam).

This makam consists of an Uşşâk tetrachord plus a Bûselik pentachord on the note Neva (D); this is labelled (1) below. The tonic is A (Dügâh), the dominant—here actually a subdominant—is D (Neva), and the leading tone—here actually a subtonic—is G (Rast). Additionally, there is a development in the makam's lower register, which consists of a Rast pentachord on the note D (Yegâh); this is labeled (1A) below.

1)

1A)

In Turkey, the particular call to prayer which occurs around noon and is called öğle is most often recited using the Uşşak makam.

Acem makam

- See Ajam (maqam).

Notes

- Beken and Signell 2006,.

- "https://www.pegem.net:TÜRK MUSİKÎSİ TEORİK VE UYGULAMALI BİLGİLERİNİN, EĞİTİM VE ÖĞRETİMDE VERİLEBİLMESİNE İLİŞKİN BİR MODEL ÖNERİSİ" (PDF). Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- Habib Hassan Touma - Review of Das arabische Tonsystem im Mittelalter by Liberty Manik. doi:10.2307/

- Shupo, Sokol, ed., Urban Music in the Balkans. Tirana:ASMUS, 2006

Sources

- Beken, Münir, and Karl Signell. "Confirming, delaying, and deceptive elements in Turkish improvisation," Maqām Traditions of Turkic Peoples: Proceedings of the Fourth Meeting of the ICTM Study Group "maqām", Istanbul, 18–24 October 1998, edited by Jürgen Elsner and Gisa Jähnishen, in collaboration with Theodor Ogger and Ildar Kharissov, Berlin: trafo verlag Dr. Wolfgang Weist, 2006. ISBN 3-89626-657-8 http://www.umbc.edu/eol/makam/2008Kongre/confirming.html

Further reading

- Aydemir, Murat. Turkish music makam guide. Pan Yayıncılık, 2010. ISBN 9789944396844.

- Mikosch, Thomas. Makamlar: The Musical Scales of Turkey. S.l.: Lulu.com, 2017. ISBN 978-0244325602.

- Özkan, İsmail Hakkı. Türk Mûsıkîsi Nazariyatı ve Usûlleri. Kudüm Velveleleri. Ötüken, 2000. ISBN 975-437-017-6.

- Signell, Karl L. Makam: Modal Practice in Turkish Art Music. Nokomis FL (USA): Usul editions/Lulu.com., 2004. ISBN 0-9760455-0-8. "Unabridged reprint of the 1986 hard cover edition with updates, corrections, introduction, audio and other supplements". Originally published: Asian Music Publications, Series D: Monographs, no. 4. Seattle: Asian Music Publications, 1977.

- Signell, Karl L. Makam: Türk Sanat Musikisinde Makam Uygulaması (Turkish translation of above). Istanbul: Yapı Kredi Kültür Sanat Yayıncılık, 2006. ISBN 975-08-1080-5.

- Yılmaz, Zeki. Türk Mûsıkîsi Dersleri. Istanbul: Çağlar Yayınları, 2001. ISBN 975-95729-1-5.

External links

- Klasik Türk (Tasavvuf) Musikisi İlahi Peşrev Saz semaisi ve Taksim nota ve mp3 kayıtları

- Cinuçen Tanrıkorur, "The Ottoman Music", translated by Savaş Ş. Barkçin, https://web.archive.org/web/20061215165158/http://www.turkmusikisi.com/osmanli_musikisi/the_ottoman_music.htm

- Maqam World

- Maqam World: What is a Maqam?

- Sephardic Pizmonim Project- Jewish use of Makam