Turukkaeans

The Turukkaeans were a Bronze and Iron Age people of Mesopotamia and the Zagros Mountains, in South West Asia. Their endonym has sometimes been reconstructed as Tukri.

A significant early reference to them is an inscription by the Babylonian king Hammurabi, (r. circa 1792 – c. 1752 BCE) that mentions a kingdom named Tukriš (UET I l. 46, iii–iv, 1–4), alongside Gutium, Subartu and another name that is usually reconstructed as Elam. Other texts from the same period refer to the kingdom as Tukru. By the early part of the 1st millennium BCE, names such as Turukkum, Turukku and ti-ru-ki-i are being used for the same region. In a broader sense, names such as Turukkaean been used in a generic sense to mean "mountain people" or "highlanders".

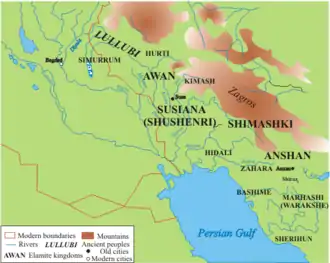

Tukru or Turukkum was said to have spanned the north-east edge of Mesopotamia and an adjoining part of the Zagros Mountains (modern Iraq and Iran). In particular, they were associated with the Lake Urmia basin and the valleys of the north-west Zagros. They were therefore located north of ancient Lullubi, and at least one Neo-Assyrian (9th to 7th centuries BCE) text refers to the whole area and its peoples as "Lullubi-Turukki" (VAT 8006).

Turukku was regarded by the Old Assyrian Empire as a constant threat, during the reign of Shamshi-Adad I (1813-1782 BCE) and his son and successor Ishme-Dagan (1781-1750 BCE). The Turukkaeans were reported to have sacked the city of Mardaman around the year 1769/68 BCE.[1] Babylon's defeat of Turukku was celebrated in the 37th year of Hammurabi's reign (c. 1773 BCE).

In terms of cultural and linguistic characteristics, little is known about the Tukri. They are described by their contemporaries as a semi-nomadic, mountain tribe, who wore animal skins. Some scholars believe they may have been Hurrian-speaking or subject to a Hurrian elite.[2]

Footnotes

- Pfälzner, Peter, (2018). "Keilschrifttafeln von Bassetki lüften Geheimnis um Königsstadt Mardaman". uni-tuebingen.de. University of Tubingen.

- Læssøe, Jørgen (2014-10-24). People of Ancient Assyria: Their Inscriptions and Correspondence. Routledge. ISBN 9781317602613.

Bibliography

- German Archaeological Institute. Department of Tehran Archaeological releases from Iran, Volume 19, Dietrich Reimer, 1986 (in German)

- Wayne Horowitz, Mesopotamian Cosmic Geography. Winona Lake; Eisenbrauns, 1998.

- Jesper Eidem, Jørgen Læssøe, The Shemshara archives, Volume 23. Copenhagen, Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters, 2001. ISBN 8778762456

- Jörgen Laessøe, The Shemshāra Tablets. Copenhagen, 1959.

- Jörgen Laessøe, "The Quest for the Country of *Utûm", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 1968, vol. 88 , no. 1, pp. 120–122.

- Victor Harold Matthews, Pastoral nomadism in the Mari Kingdom (ca. 1830-1760 B.C.). American Schools of Oriental Research, 1978. ISBN 0897571037

- Peter Pfälzner, Keilschrifttafeln von Bassetki lüften Geheimnis um Königsstadt Mardaman (webpage; German language), University of Tubingen, 2018.

- Daniel T. Potts, Nomadism in Iran: From Antiquity to the Modern Era. Oxford; Oxford University Press, 2014.