Zagros Mountains

The Zagros Mountains (Persian: کوههای زاگرس; Kurdish: چیاکانی زاگرۆس, romanized: Çiyayên Zagros;[2][3]) are a long mountain range in Iran, northern Iraq and southeastern Turkey. This mountain range has a total length of 1,600 km (990 mi). The Zagros mountain range begins in northwestern Iran and roughly follows Iran's western border, while covering much of southeastern Turkey and northeastern Iraq. From this border region, the range roughly follows Iran's coast on the Persian Gulf. It spans the whole length of the western and southwestern Iranian plateau, ending at the Strait of Hormuz. The highest point is Mount Dena, at 4,409 metres (14,465 ft).

| Zagros | |

|---|---|

Dena, highest point in the Zagros Mountains | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Qash-Mastan (Dena) |

| Elevation | 4,409 m (14,465 ft) |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | 1,600[1] km (990 mi) |

| Width | 240[1] km (150 mi) |

| Naming | |

| Native name | زاگرۆس |

| Geography | |

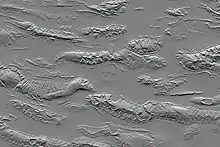

The Zagros fold and thrust belt in green, with the Zagros Mountains to the right

| |

| Location | Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey Middle East or Western Asia |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | Carboniferous |

| Mountain type | Fold and thrust belt |

Geology

The Zagros fold and thrust belt was mainly formed by the collision of two tectonic plates, the Eurasian Plate and the Arabian Plate.[5] This collision mainly happened during the Miocene (about 25–5 million years ago or mya) and folded the entirety of the rocks that had been deposited from the Paleozoic (541–242 mya) to the Cenozoic (66 mya – present) in the passive continental margin on the Arabian Plate. However, the obduction of Neotethys oceanic crust during the Cretaceous (145–66 mya), and the continental arc collision in the Eocene (56–34 mya) both had major effects on uplifts in the northeastern parts of the belt.

The process of collision continues to the present, and as the Arabian Plate is being pushed against the Eurasian Plate, the Zagros Mountains and the Iranian Plateau are getting higher and higher. Recent GPS measurements in Iran[6] have shown that this collision is still active and the resulting deformation is distributed non-uniformly in the country, mainly taken up in the major mountain belts like Alborz and Zagros. A relatively dense GPS network which covered the Iranian Zagros[7] also proves a high rate of deformation within the Zagros. The GPS results show that the current rate of shortening in the southeast Zagros is ~10 mm/a (0.39 in/year), dropping to ~5 mm/a (0.20 in/year) in the northwest Zagros. The north-south Kazerun strike-slip fault divides the Zagros into two distinct zones of deformation. The GPS results also show different shortening directions along the belt, normal shortening in the southeast, and oblique shortening in the northwest Zagros. The Zagros mountains were created around the time of the second ice age, which caused the tectonic collision, leading to its uniqueness.

The sedimentary cover in the SE Zagros is deforming above a layer of rock salt (acting as a ductile decollement with a low basal friction), whereas in the NW Zagros the salt layer is missing or is very thin. This different basal friction is partly responsible for the different topographies on either side of the Kazerun fault. Higher topography and narrower zone of deformation in the NW Zagros is observed whereas in the SE, deformation was spread more and a wider zone of deformation with lower topography was formed.[8] Stresses induced in the Earth's crust by the collision caused extensive folding of the preexisting layered sedimentary rocks. Subsequent erosion removed softer rocks, such as mudstone (rock formed by consolidated mud) and siltstone (a slightly coarser-grained mudstone) while leaving harder rocks, such as limestone (calcium-rich rock consisting of the remains of marine organisms) and dolomite (rocks similar to limestone containing calcium and magnesium). This differential erosion formed the linear ridges of the Zagros Mountains.

The depositional environment and tectonic history of the rocks were conducive to the formation and trapping of petroleum, and the Zagros region is an important area for oil production. Salt domes and salt glaciers are a common feature of the Zagros Mountains. Salt domes are an important target for petroleum exploration, as the impermeable salt frequently traps petroleum beneath other rock layers. There is also much water-soluble gypsum in the region.[9]

Type and age of rock

The mountains are completely of sedimentary origin and are made primarily of limestone. In the Elevated Zagros or the Higher Zagros, the Paleozoic rocks can be found mainly in the upper and higher sections of the peaks of the Zagros Mountains, along the Zagros main fault. On both sides of this fault, there are Mesozoic rocks, a combination of Triassic (252–201 mya) and Jurassic (201–145 mya) rocks that are surrounded by Cretaceous rocks on both sides. The Folded Zagros (the mountains south of the Elevated Zagros and almost parallel to the main Zagros fault) is formed mainly of Tertiary rocks, with the Paleogene (66–23 mya) rocks south of the Cretaceous rocks and then the Neogene (23–2.6 mya) rocks south of the Paleogene rocks. The mountains are divided into many parallel sub-ranges (up to 10 or 250 km (6.2 or 155.3 mi) wide), and orogenically have the same age as the Alps.

Iran's main oilfields lie in the western central foothills of the Zagros mountain range. The southern ranges of the Fars Province have somewhat lower summits, reaching 4,000 metres (13,000 feet). They contain some limestone rocks showing abundant marine fossils.[8]

History

The Zagros Mountains were occupied by early humans since the Lower Paleolithic Period. The earliest human fossils discovered in Zagros belongs to Neanderthals and come from Shanidar Cave, Bisitun Cave, and Wezmeh Cave. The remains of ten Neanderthals, dating from around 65,000-35,000 years ago, have been found in the Shanidar Cave.[10] The cave also contains two later "proto-Neolithic" cemeteries, one of which dates back about 10,600 years and contains 35 individuals.[11] Coon who excavated Bisitun Cave described two hominid remains from the site, a maxilliary upper incisor and a radius shaft fragment, both from a Layer designated F+. These remains were listed but never described fully for the palaeontological community. When they were finally reexamined four decades later, the incisor was found to be of bovine, rather than hominid origin.[8] The radius fragment was found to show Neanderthal affinities, as it is mediolaterally expanded at the interosseus crest. Metrically, it is outside the range of variation of early anatomically modern humans, but in the range of Neanderthals and early Upper Paleolithic humans.[12]

The radius fragment also showed signs of scavenging carnivores or rodents, such as jackal and fox, the remains of which were also found at the site. Wezmeh Child or Wezmeh 1 represented by an isolated unerupted human maxillary right premolar tooth (P3 or possibly P4) of an individual between 6–10 years old.[13] Evidence from later Upper Paleolithic and Epipaleolithic occupations come from Yafteh Cave, Kaldar Cave near Khoramabad, and Warwasi, Malaverd near Kermanshah, Kenacheh Cave in Kurdistan, Boof Cave in Fars and a number of other caves and rock shelters.[14]

Signs of early agriculture date back as far as 9000 BC in the foothills of the mountains.[15] Some settlements later grew into cities, eventually named Anshan and Susa; Jarmo is one archaeological site in this area. Some of the earliest evidence of wine production has been discovered in the mountains; both the settlements of Hajji Firuz Tepe and Godin Tepe have given evidence of wine storage dating between 3500 and 5400 BC.[16]

During early ancient times, the Zagros was the home of peoples such as the ancestors of the Sumerians and, later, the Kassites, Guti, Elamites and Mitanni, who periodically invaded the Sumerian and/or Akkadian cities of Mesopotamia. The mountains create a geographic barrier between the Mesopotamian Plain, which is in Iraq, and the Iranian Plateau. A small archive of clay tablets detailing the complex interactions of these groups in the early second millennium BC has been found at Tell Shemshara along the Little Zab.[17] Tell Bazmusian, near Shemshara, was occupied between 5000 BCE and 800 CE, although not continuously.[18]

Climate

The mountains contain several ecosystems. Prominent among them are the forest and forest steppe areas with a semi-arid climate. As defined by the World Wildlife Fund and used in their Wildfinder, the particular terrestrial ecoregion of the mid to high mountain area is Zagros Mountains forest steppe (PA0446). The annual precipitation ranges from 400–800 mm (16–31 in) and falls mostly in winter and spring. Winters are severe, with low temperatures often below −25 °C (−13 °F). The region exemplifies the continental variation of the Mediterranean climate pattern, with a snowy winter and mild, rainy spring, followed by a dry summer and autumn.[19]

| Climate data for Amadiya District, Iraq | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | −0.2 (31.6) |

1.4 (34.5) |

6.4 (43.5) |

12.2 (54.0) |

19.3 (66.7) |

24.8 (76.6) |

29.7 (85.5) |

29.6 (85.3) |

25.6 (78.1) |

17.7 (63.9) |

9.7 (49.5) |

2.7 (36.9) |

14.9 (58.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −8.0 (17.6) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

3.5 (38.3) |

8.8 (47.8) |

13.0 (55.4) |

17.3 (63.1) |

16.9 (62.4) |

13.0 (55.4) |

7.2 (45.0) |

2.1 (35.8) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

5.1 (41.1) |

| Source: [20] | |||||||||||||

Glaciation

The mountains of the East-Zagros, the Kuh-i-Jupar (4,135 m (13,566 ft)), Kuh-i-Lalezar (4,374 m (14,350 ft)) and Kuh-i-Hezar (4,469 m (14,662 ft)) do not currently have glaciers. Only at Zard Kuh and Dena some glaciers still survive. However, before the Last Glacial Period they had been glaciated to a depth in excess of 1,900 metres (1.2 miles), and during the Last Glacial Period to a depth in excess of 2,160 metres (7,090 feet). Evidence exists of a 20 km (12 mi) wide glacier fed along a 17 km (11 mi) long valley dropping approximately 1,600 m (5,200 ft) along its length on the north side of Kuh-i-Jupar with a thickness of 350–550 m (1,150–1,800 ft). Under conditions of precipitation comparable to current climatic record-keeping, this size of glacier could be expected to form where the annual average temperature was between 10.5 and 11.2 °C (50.9 and 52.2 °F), but since conditions are expected to have been dryer during the period in which this glacier was formed, the temperature must have been lower.[21][22][23][24]

Flora and fauna

.JPG.webp)

Although currently degraded through overgrazing and deforestation, the Zagros region is home to a rich and complex flora. Remnants of the originally widespread oak-dominated woodland can still be found, as can the park-like pistachio/almond steppelands. The ancestors of many familiar foods, including wheat, barley, lentil, almond, walnut, pistachio, apricot, plum, pomegranate and grape can be found growing wild throughout the mountains.[26] Persian oak (Quercus brantii) (covering more than 50% of the Zagros forest area) is the most important tree species of the Zagros in Iran.[27]

Other floral endemics found within the mountain range include: Allium iranicum, Astragalus crenophila, Bellevalia kurdistanica, Cousinia carduchorum, Cousinia odontolepis, Echinops rectangularis, Erysimum boissieri, Iris barnumiae, Ornithogalum iraqense, Scrophularia atroglandulosa, Scorzonera kurdistanica, Tragopogon rechingeri, and Tulipa kurdica.[28] The Zagros are home to many threatened or endangered organisms, including the Zagros Mountains mouse-like hamster (Calomyscus bailwardi), the Basra reed-warbler (Acrocephalus griseldis) and the striped hyena (Hyena hyena). Luristan newt (Neurergus kaiseri) - vulnerable endemic to the central Zagros mountains of Iran. The Persian fallow deer (Dama dama mesopotamica), an ancient domesticate once thought extinct, was rediscovered in the late 20th century in Khuzestan Province, in the southern Zagros. Also, Wild Goats can be found almost all over the Zagros mountain range.

In the late 19th century, the Asiatic lion (Panthera leo persica)[29] inhabited the southwestern part of the mountains. It is now extinct in this region.[30]

Religion

The entrance to the ancient Mesopotamian underworld was believed to be located in the Zagros Mountains in the far east.[31] A staircase led down to the gates of the underworld.[31] The underworld itself is usually located even deeper below ground than the Abzu, the body of freshwater which the ancient Mesopotamians believed lay deep beneath the earth.[31]

Gallery

A road through the mountains in Iraqi Kurdistan

A road through the mountains in Iraqi Kurdistan Wild Goat Herd, Zagros, Behbahan

Wild Goat Herd, Zagros, Behbahan Fritillaria Imperialis in Dena, Iranian Zagros

Fritillaria Imperialis in Dena, Iranian Zagros

See also

- Alborz Mountains

- Al Hajar Mountains, technically a continuation of the Zagros in the Arabian Peninsula

- Caucasus Mountains

- Kurdistan

- Kurds

- Mount Alvand

- Mount Arbaba

- Mount Derak

- Mount Elbrus

- Mount Judi

- Qaleh gorikhteh

- Silakhor Plain

- Taurus Mountains

- Wildlife of Iran

- Wildlife of Iraq

- Wildlife of Turkey

![]() Kurdistan portal

Kurdistan portal

References

- "Zagros Mountains". Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- "Li Îranê 66 Kes di Ketina Firokeka Bazirganî de Têne Kuştin". VOA (Dengê Amerika) (in Kurdish). 18 February 2018. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- "چەند دیمەنێکی زنجیرە چیاکانی زاگرۆس". Basnews (in Kurdish). Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- "Salt Dome in the Zagros Mountains, Iran". NASA Earth Observatory. Retrieved 2006-04-27.

- Scheffel, Richard L.; Wernet, Susan J., eds. (1980). Natural Wonders of the World. United States of America: Reader's Digest Association, Inc. pp. 422–423. ISBN 0-89577-087-3.

- Nilforoushan F., Masson F., Vernant P., Vigny C., Martinod J., Abbassi M., Nankali H., Hatzfeld D., Bayer R., Tavakoli F., Ashtiani A., Doerflinger E., Daignières M., Collard P., Chéry J., 2003. "GPS network monitors the Arabia-Eurasia collision deformation in Iran." Journal of Geodesy, 77, 411–422.

- Hessami K., Nilforoushan F., Talbot CJ., 2006, "Active deformation within the Zagros Mountains deduced from GPS measurements," Journal of the Geological Society, London, 163, 143–148.

- Nilforoushan F, Koyi HA., Swantesson J.O.H., Talbot CJ., 2008, "Effect of basal friction on the surface and volumetric strain in models of convergent settings measured by laser scanner," Journal of Structural Geology, 30, 366–379.

- https://nsf.gov/news/mmg/mmg_disp.jsp?med_id=72763&from=

- Murray, Tim (2007). Milestones in Archaeology: A Chronological Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 454. ISBN 9781576071861.

- Ralph S. Solecki; Rose L. Solecki & Anagnostis P. Agelarakis (2004). The Proto-Neolithic Cemetery in Shanidar Cave. Texas A&M University Press. pp. 3–5. ISBN 9781585442720.

- Trinkaus, E and F. Biglari (2006) Middle Paleolithic Human Remains from Bisitun Cave, Iran, Paleorient: 32.2: 105- 111

- Zanolli, Clément, Fereidoun Biglari, Marjan Mashkour, Kamyar Abdi, Herve Monchot, Karyne Debue, Arnaud Mazurier, Priscilla Bayle, Mona Le Luyer, Hélène Rougier, Erik Trinkaus, Roberto Macchiarelli. (2019). Neanderthal from the Central Western Zagros, Iran. Structural reassessment of the Wezmeh 1 maxillary premolar. Journal of Human Evolution, Vol: 135.

- Shidrang S, (2018) The Middle to Upper Paleolithic Transition in the Zagros: The Appearance and Evolution of the Baradostian, In The Middle and Upper Paleolithic Archeology of the Levant and Beyond, Y. Nishiaki, T. Akazawa (eds.), pp. 133-156, Replacement of Neanderthals by Modern Humans Series, Tokyo.

- La Mediterranée, Braudel, Fernand, 1985, Flammarion, Paris

- Phillips, Rod. A Short History of Wine. New York: Harper Collins. 2000.

- Eidem, Jesper; Læssøe, Jørgen (2001), The Shemshara archives 1. The letters, Historisk-Filosofiske Skrifter, 23, Copenhagen: Kongelige Danske videnskabernes selskab, ISBN 87-7876-245-6

- Al-Soof, Behnam Abu (1970). "Mounds in the Rania Plain and excavations at Tell Bazmusian (1956)". Sumer. 26: 65–104. ISSN 0081-9271.

- Frey, W.; W. Probst (1986). Kurschner, Harald (ed.). "A synopsis of the vegetation in Iran". Contributions to the Vegetation of Southwest Asia. Wiesbaden, Germany: L. Reichert: 9–43. ISBN 3-88226-297-4.

- "Climate statistics for Amadiya". Meteovista. Retrieved September 6, 2014.

- Kuhle, M. (1974):Vorläufige Ausführungen morphologischer Feldarbeitsergebnisse aus den SE-Iranischen Hochgebirgen am Beispiel des Kuh-i-Jupar. Zeitschrift für Geomorphologie N.F., 18, (4), pp. 472-483.

- Kuhle, M. (1976):Beiträge zur Quartärgeomorphologie SE-Iranischer Hochgebirge. Die quartäre Vergletscherung des Kuh-i-Jupar. Göttinger Geographische Abhandlungen, 67, Vol. I, pp. 1-209; Vol. II, pp. 1-105.

- Kuhle, M. (2007):The Pleistocene Glaciation (LGP and pre-LGP, pre-LGM) of SE-Iranian Mountains exemplified by the Kuh-i-Jupar, Kuh-i-Lalezar and Kuh-i-Hezar Massifs in the Zagros. Polarforschung, 77, (2-3), pp. 71-88. (Erratum/ Clarification concerning Figure 15, Vol. 78, (1-2), 2008, p. 83.

- Elsevier: Ehlers. "Quaternary Glaciations - Extent and Chronology Volume 15: A closer look Welcome". booksite.elsevier.com.

- Sevruguin, A. (1880). "Men with live lion". National Museum of Ethnology in Leiden, The Netherlands; Stephen Arpee Collection. Retrieved 2018-03-26.

- Cowan, edited by C. Wesley; Nancy L. Benco; Patty Jo Watson (2006). The origins of agriculture : an international perspective ([New ed.]. ed.). Tuscaloosa, Ala.: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-5349-6. Retrieved 5 May 2012.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- M. Heydari; H. Poorbabaei; T. Rostami; M. Begim Faghir; A. Salehi; R. Ostad Hashmei (2013). "Plant species in Oak (Quercus brantii Lindl.) understory and their relationship with physical and chemical propertiesof soil in different altitude classes in the Arghvan valley protected area, Iran" (PDF). Caspian Journal of Environmental Sciences, 2013, Vol. 11 No.1, pp. 97~110. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- "Haji Omran Mountain (IQ018)" (PDF). natrueiraq.org. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- Kitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V.; Christiansen, P.; Driscoll, C.; Duckworth, J. W.; Johnson, W.; Luo, S.-J.; Meijaard, E.; O’Donoghue, P.; Sanderson, J.; Seymour, K.; Bruford, M.; Groves, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Nowell, K.; Timmons, Z.; Tobe, S. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group" (PDF). Cat News. Special Issue 11.

- Heptner, V. G.; Sludskij, A. A. (1992) [1972]. "Lion". Mlekopitajuščie Sovetskogo Soiuza. Moskva: Vysšaia Škola [Mammals of the Soviet Union. Volume II, Part 2. Carnivora (Hyaenas and Cats)]. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution and the National Science Foundation. pp. 82–95. ISBN 90-04-08876-8.

- Black, Jeremy; Green, Anthony (1992), Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary, Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, p. 180, ISBN 0714117056

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zagros Mountains. |

- Zagros, Photos from Iran, Livius.

- The genus Dionysia

- Iran, Timeline of Art History

- Mesopotamia 9000–500 B.C.

- Major Peaks of the Zagros Mountains