Tye Leung Schulze

Tye Leung Schulze (August 24, 1887 – March 10, 1972) became the first Chinese American woman to vote in the United States when she cast a ballot in San Francisco on May 19, 1912. She also became the first Chinese American woman to pass the civil service exams and to occupy a government job. The San Francisco Call stated that she was "the first Chinese woman in the history of the world to exercise the electoral franchise." Schulze was also the first Chinese woman hired to work at Angel Island.[1] She is a designated Women's History Month Honoree by the National Women's History Project.[2]

Tye Leung Schulze | |

|---|---|

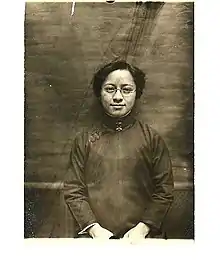

Tye Leung Schulze in 1912 | |

| Born | Tye Leung August 24, 1887 |

| Died | March 10, 1972 |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Interpreter |

| Known for | First Chinese American woman to cast a ballot in a presidential primary election. |

| Tye Leung Schulze | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 梁亞娣 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Employment

In 1901, Leung was saved from an arranged marriage to an older Montana man by Donaldina Cameron, who led the Presbyterian Mission Home in San Francisco.[3][4] At the Mission, Leung learned to speak English, converted to Christianity, and helped Cameron and local police rescue Chinese slaves and prostitutes from brothels.[5] She also served as an interpreter for the Mission.[6][7] She interpreted for girls from Chinatown in the courts, thus becoming widely respected in local courts.[5] Leung worked for the Mission Home for about nine years, and developed a close relationship with Cameron.[5][6] Cameron nicknamed her “Tiny” because Leung stood a little over four feet tall.[5] In 1910, when the Angel Island immigration station opened, Cameron recommended Leung to take a job at the Angel Island Immigration Station as an interpreter for Chinese immigrants.[6][8]

Leung was the first Chinese American to pass the civil service examinations[9] and she was hired to work as an assistant to the matron at the Angel Island Immigration Station. The matron who received her commission from Washington D.C. previously came from the Immigration Bureau on Ellis Island.[4] Leung was also the first Chinese woman to be appointed by the federal government.[10] At Angel Island, she would work with Chinese immigrants who were detained for physical examinations and interrogation upon their arrival. When interviewed about her experience working at Angel Island, Leung said:

“Dull?—never. Always sitting there listening to my countrymen. I listen for little scraps about the great new movement over the sea, that is setting them free over there as I have been set free here.”[5]

After losing her job at Angel Island due to her marriage with Charles Schulze, Leung spent many years providing interpretation and social services to San Francisco's Chinatown residents. For a year, she worked at the Chinese Tea Garden.[5] She served as an administrative clerk, bookkeeper, and social worker at the San Francisco Chinese Hospital to support her family.[9][11][5] Beginning in 1926 for 20 years, Leung went to work as a night-shift PBX operator for the Pacific Telephone's China Exchange in Chinatown, a higher-class job for women at the time.[3][9][5][11] She facilitated the lives of many Chinese Americans by connecting them with lawyers, courts, and immigration services.[6] As a telephone operator, she had to memorize telephone numbers for everyone and every store in Chinatown.[11] She became respected across Chinatown for her skills and connections in assisting Chinese Americans. Leung’s son, Fred, recalled that “she was always asked to interpret. GI brides, immigration, court cases. She never refused to help.”[11]

In 1946, Leung was hired by the Immigration Office to work as an interpreter for a year.[5] Since the War Brides Act of 1945 was enacted, lifting the temporary ban on Asian immigration, many Chinese wives were joining their husbands in the United States, creating the need for translators.[5]

For members of the Chinese community in San Francisco, Leung also offered her translation services. These translations helped to make her a community fixture.[12]

Suffrage work

In May of 1912, Leung was the first Chinese woman to vote in a presidential primary election.[3][13] Leung who was in her early twenties, may have also been the first Chinese woman worldwide to cast a vote.[14][11] At the time of her vote, she was still living and working for the Presbyterian Mission House, which is known as the Cameron House today.[13][15] Leung voted at a polling place at Powell and Pacific streets in San Francisco.[13] After voting the San Francisco Examiner called the vote "the last word in the modern movement for the complete enfranchisement of women...It was the latest achievement in the great American work of amalgamating and lifting up all the races of the earth."[9]

The San Francisco Examiner stated that Leung was “altogether familiar with the political issues involved in the primary presidential election.”[13] Leung was interviewed about her experience with her first vote:

"My first vote? – Oh, yes, I thought long over that. I studied; I read about all your men who wished to be president. I learned about the new laws. I wanted to KNOW what was right, not to act blindly...I think it right we should all try to learn, not vote blindly, since we have been given this right to say which man we think is the greatest...I think too that we women are more careful than the men. We want to do our whole duty more. I do not think it is just the newness that makes use like that. It is conscience."[14]

In 1911, the year before Leung cast her first vote, California became the sixth state to pass laws that granted equal suffrage, after Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, Idaho, and Washington.[16] California’s suffrage laws were passed nearly a decade before the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920

Marriage

While working at Angel Island she met immigration inspector Charles Frederick Schulze. Schulze was Caucasian and the intermarriage of Chinese and white Americans was illegal as a result of California's anti-miscegenation laws in 1913.[14] As a result, the couple went to Vancouver, Washington to be legally married.[3] They were married in October 1913.[9] The couple's families, however, did not approve of their marriage.[5] After the marriage the couple came back to California, but both lost their government jobs due to racial prejudice. They had four children: Frederick, Theodore, Louise, and Donaldina.[6][17]

After losing his job, Schulze went to work shortly as a special patrol officer and street-car motorman.[11] He then worked for the Southern Pacific Company as an "inspector of office machines", and then as a superintendent of service for the Columbia Gramaphone Company.[18] Schulze passed away in 1935.[14]

Other Social Activism

When abortion was illegal, 61-year-old Leung, along with four others, were arrested for their roles in what was believed to be a statewide abortion ring.[19] Leung was tipped off by a San Francisco girl who was flown to Los Angeles for an abortion that cost $400.[19] Following an investigation and trial, charges against Leung were dropped in December 1948.[14]

Personal life

.jpg.webp)

Tye Leung was born on August 24th in San Francisco, California in 1887. She was the youngest of five sisters and two brothers to Chinese immigrants from the Guangdong province.[11][5][6] Her father was a Chinese cobbler, earning $20 a month, while her mother ran a boarding house.[11] Leung’s family of ten and a few other relatives lived in a cramped two-room apartment on Ross Alley in San Francisco’s Chinatown.[11][6] Leung was sent to Presbyterian school to learn English, and was often taken to church meetings, which were her earliest exposures to Christianity.[5][6]

When she was nine, Leung was sent by her mother to work as a “servant” in another household, not realizing that she had been sold to another family.[5] Leung’s uncle, who realized her situation, consulted Leung’s school teachers who arranged for her to return home.[5] Later as a teenager she was placed in an arranged marriage to a man from Butte, Montana. Leung’s older sister, who was originally to be married to the man, had escaped the marriage by running away with her boyfriend.[6] As a result, her parents intended for Leung to marry the same man.[6] At 14 she was saved from the arranged marriage by Donaldina Cameron of the Presbyterian Mission Home.

When pinball machines were introduced to Chinatown in the 1930s, Leung built a reputation for herself locally as a pinball wizard.[14][11] She was famously photographed in a Studebaker.[14][11] Many compared Leung to Sun Yat-sen, who also embraced democracy and had an affinity for Studebaker convertibles.[5] Leung passed at the age of 84 in San Francisco on March 10, 1972.[3][17]

--Robin Kadison Berson[9]

Legacy

Leung was recognized for her contributions to women's history in 1987 in the San Bernardino Sun newspaper.[20] In October 2011 the story of Tye Leung Schulze was told through a play starring actress Lily Tung.[21]

Further reading

- Yung, Judy. Unbound Voices: A Documentary History of Chinese Women in San Francisco. Berkeley: University of California Press (1999). ISBN 0-520-21860-4

References

- "Voting". Chinese American Women: A History of Resilience and Resistance. National Women's History Museum. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- "Monique Mehta". Women's History Month. National Women's History Project. 2007. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- Lily Xiao Hong Lee; A. D. Stefanowska (1998). Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: The Qing Period, 1644–1911. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 185–. ISBN 978-0-7656-0043-1. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- "22 Feb 1910, p. 11 – San Francisco Chronicle at Newspapers.com". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- "Immigrant Voices: Discover Immigrant Stories from Angel Island". AIISFIV.org. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- "Tye Leung Schulze". Encyclopedia of the American West. 1996.

- "Immigrant Voices: Discover Immigrant Stories from Angel Island". AIISFIV.org. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- Ngai, Mae M. (2011). ""A Slight Knowledge of the Barbarian Language": Chinese Interpreters in Late-Nineteenth and Early-Twentieth-Century America". Journal of American Ethnic History. 30 (2): 5–32. doi:10.5406/jamerethnhist.30.2.0005. ISSN 0278-5927. JSTOR 10.5406/jamerethnhist.30.2.0005.

- Robin Kadison Berson (1994). Marching to a different drummer: unrecognized heroes of American history. ABC-CLIO. pp. 288–292. ISBN 978-0-313-28802-9. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- "20 Mar 1910, p. 39 – Omaha Daily Bee at Newspapers.com". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2019-12-04.

- "2 Apr 1980, 62 – The San Francisco Examiner at Newspapers.com". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- "Tye Leung Schulze (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2020-08-25.

- "15 May 1912, 1 – The San Francisco Examiner at Newspapers.com". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- "Tye Leung Schulze". Retrieved June 6, 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "Cameron House". Cameron House. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- Keeping the Republic: Power and Citizenship in American Politics. CQ Press. 2019. ISBN 978-1544326030.

- "15 Mar 1972, 51 – The San Francisco Examiner at Newspapers.com". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- Original business cards of Charles Schulze

- "2 Apr 1950, p. 1 – The San Bernardino County Sun at Newspapers.com". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- "San Bernardino County Salutes Women's History Month". San Bernardino Sun. 1 March 1987. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- Lovelie Faustino (2011). "Lily Tung Crystal portrays first Chinese American woman vote". Daily Dose: 10/13/11. AsianWeek. Archived from the original on 18 October 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2011.