U.S.–Japan Alliance

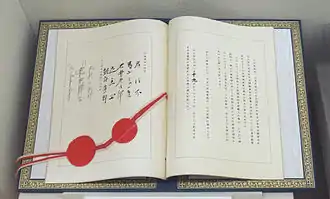

The U.S.–Japan Alliance (日米同盟, Nichi-Bei Dōmei) is a military alliance between Japan and the United States of America, as codified in the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security Between the United States and Japan, which was first signed in 1951, took effect in 1952, and was amended in 1960. The alliance has further been codified in a series of "administrative" agreements, "status of forces" agreements, and secret pacts (密約, mitsuyaku) that have not been subject to legislative review in either country.

Under the terms of the alliance, the United States undertakes to defend Japan in case of attack by a third power, and in return Japan allows U.S. military troops to be stationed on Japanese soil, and makes sizeable "sympathy payments" to underwrite the cost of U.S. bases in Japan. More U.S. military troops are stationed on Japanese soil than in any nation other than the United States.[1] In practice, the commitment to defend Japan from attack includes extending the United States's "nuclear umbrella" to encompass the Japanese isles.

The two nations also share defense technology on a limited basis, work to ensure interoperability of their respective military forces, and frequently participate in joint military exercises.[1]

Although Article 9 of Japan's Constitution forbids Japan from maintaining offensive military capabilities, Japan has supported large-scale U.S. military operations such as the Gulf War and the Iraq War with monetary contributions and dispatch of noncombat ground forces.

Formation

The U.S.-Japan alliance was forced on Japan as a condition of ending the U.S.-led military occupation of Japan (1945-1952).[2] The original U.S.-Japan Security Treaty was signed on September 8, 1951, in tandem with the signing of the San Francisco Peace Treaty ending World War II in Asia, and took effect in conjunction with the official end of the occupation on April 28, 1952.[2]

The original Security Treaty had no specified end date or means of abrogation, allowed US forces stationed in Japan to be used for any purpose without prior consultation with the Japanese government, had a clause specifically authorizing US troops to put down domestic protests in Japan, and did not commit the United States to defend Japan if Japan were to be attacked by a third party.[2]

Because the original treaty was so one-sided, it was the target of protests in Japan throughout the 1950s, most notably the "Bloody May Day" protests of May 1, 1952,[3] and Japanese leaders constantly entreated with US leaders to revise it.

1950s anti-base protests in Japan

Even after the occupation ended in 1952, the United States maintained large numbers of military troops on Japanese soil. In the mid-1950s there were still 260,000 troops in Japan, utilizing 2,824 facilities throughout the nation (excluding Okinawa), and occupying land totaling 1,352 square kilometres.[3]

The large number of bases and U.S. military personnel produced frictions with the local population and led to a series of contentious anti-base protests, including the Uchinada protests of 1952-53, the Sunagawa Struggle of 1955-57, and the Girard Incident of 1957.[4]

The growing size and scope of these disturbances helped convince the administration of U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower to significantly reduce the number of U.S. troops stationed in mainland Japan (while retaining large numbers of troops in U.S.-occupied Okinawa) and to finally renegotiate the terms of the U.S.-Japan alliance.[5]

1960 treaty revision crisis

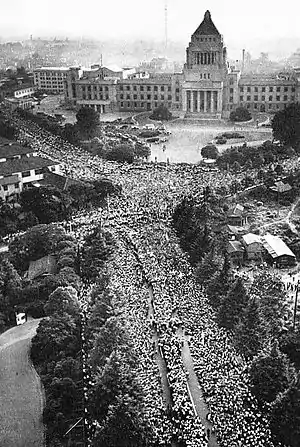

In 1960, the government of Japanese prime minister Nobusuke Kishi attempted to pass the revised Security Treaty through the Japanese Diet but was met with mass protests.

The revised treaty was a significant improvement over the original treaty, committing the United States to defend Japan in an attack, requiring prior consultation with the Japanese government before dispatching U.S. forces based in Japan overseas, removing the clause preauthorizing suppression of domestic disturbances, and specifying an initial 10-year term, after which the treaty could be abrogated by either party with one year's notice.[6]

However, many Japanese people, especially on the left, but also even some on the center and the right of the political spectrum, preferred to chart a more neutral course in the Cold War,[7] and thus decided to oppose treaty revision as means of expressing their opposition to the U.S.-Japan alliance as a whole.

When Kishi rammed the treaty through the Diet despite popular opposition, the protests escalated dramatically in size, forcing Kishi to resign as well as to cancel a planned visit by Eisenhower to Japan to celebrate the new treaty, leading to a low point in U.S.-Japan relations.[8]

Kishi and Eisenhower were succeeded by Hayato Ikeda and John F. Kennedy, respectively, who worked to repair the damage to the U.S.-Japan alliance. Kennedy and his new ambassador to Japan, Edwin O. Reischauer, pushed a new rhetoric of "equal partnership" and sought to place the alliance on a more equal footing.[9] Ikeda and Kennedy also held a summit meeting in Washington D.C. in June 1961, at which Ikeda promised greater Japanese support for U.S. Cold War policies, and Kennedy promised to treat Japan more like a close trusted ally, similar to how the United States treated Great Britain.[10]

The 1960s and 1970s: an era of secret pacts

In an effort to prevent the type of crisis that attended the revision of the Security Treaty in 1960 from happening again, both Japanese and American leaders found it more convenient going forward to alter the terms of the U.S.-Japan alliance by resort to secret pacts rather than formal revisions that would need legislative approval.[11]

In the early 1960s, Ambassador Reischauer negotiated secret agreements whereby the Japanese government allowed U.S. naval vessels to carry nuclear weapons even when transiting Japanese bases, and also to release limited amounts of radioactive wastewater into Japanese harbors.

Similarly, as part of the negotiations over the reversion of Okinawa to Japan in the late 1960s, Japanese prime minister Eisaku Satō and U.S. president Richard Nixon made a secret agreement that even after Okinawa reverted to Japanese control, the U.S. could still introduce nuclear weapons to U.S. bases in Okinawa in times of emergency, which was a contravention of Satō's publicly-stated "Three Non-Nuclear Principles."[12]

Japanese participation in the Gulf War and the Iraq War

In 1990, the United States called on its ally Japan for assistance in the Gulf War. However, then-current Japanese interpretation of its constitution forbade the overseas dispatch of Japanese military troops. Accordingly Japan contributed $9 billion of monetary support.[13]

In between the Gulf War and the start of the Iraq War in 2003, the Japanese government revised its interpretation of the Constitution, and thus during the Iraq War, Japan was able to dispatch noncombat ground forces in a logistical support role in support of U.S. operations in Iraq.[1]

Current views of the U.S.-Japan alliance in Japan

Although views of the U.S.-Japan alliance were negative in Japan when it was first formed in the 1950s, acceptance of the alliance has grown over time. According to a 2007 poll, 73.4% of Japanese citizens appreciated the U.S.-Japan alliance and welcomed the presence of U.S. forces in Japan.[14]

However, one area where antipathy toward the alliance remains high is Okinawa, which has a much higher concentration of U.S. bases than other parts of Japan, and where protest activity against the alliance remains strong. Okinawa, a relatively small island, is home to 32 separate U.S. military bases comprising 74.7% of bases in Japan, with nearly 20% of Okinawan land taken up by the bases.[15][16]

See also

References

- Maizland, Lindsay; Xu, Beina (August 22, 2019). "Backgrounder: The U.S.-Japan Security Alliance". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved October 9, 2020.

- Kapur, Nick (2018). Japan at the Crossroads: Conflict and Compromise after Anpo. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 11.

- Kapur, Nick (2018). Japan at the Crossroads: Conflict and Compromise after Anpo. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 14.

- Kapur, Nick (2018). Japan at the Crossroads: Conflict and Compromise after Anpo. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 14–17.

- Kapur, Nick (2018). Japan at the Crossroads: Conflict and Compromise after Anpo. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 17.

- Kapur, Nick (2018). Japan at the Crossroads: Conflict and Compromise after Anpo. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 17–18.

- Kapur, Nick (2018). Japan at the Crossroads: Conflict and Compromise after Anpo. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 13.

- Kapur, Nick (2018). Japan at the Crossroads: Conflict and Compromise after Anpo. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 22–33.

- Kapur, Nick (2018). Japan at the Crossroads: Conflict and Compromise after Anpo. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 53–4.

- Kapur, Nick (2018). Japan at the Crossroads: Conflict and Compromise after Anpo. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 54–74.

- Kapur, Nick (2018). Japan at the Crossroads: Conflict and Compromise after Anpo. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 68.

- "Agreed Minute to Joint Communique of United States President Nixon and Japanese Prime Minister Sato". Ryukyu-Okinawa History and Culture Website. Retrieved October 9, 2020.

- Kapur, Nick (2018). Japan at the Crossroads: Conflict and Compromise after Anpo. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 74.

- 自衛隊・防衛問題に関する世論調査 Archived 2010-10-22 at the Wayback Machine, The Cabinet Office of Japan

- Mitchell, Jon (13 May 2012). "What awaits Okinawa 40 years after reversion?". The Japan Times. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- Military Base Affairs Office, Executive Office of the Governor, Department of General Affairs, Okinawa Prefectural Government (2004). "U.S. Military Issues in Okinawa" (PDF). Okinawa Prefectural Government. p. 2. Retrieved October 9, 2020.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)