Occupation of Japan

The Allied occupation of Japan at the end of World War II was led by the United States, whose then-President Harry S. Truman appointed General Douglas MacArthur as the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, with support from the British Commonwealth. Unlike in the occupation of Germany, the Soviet Union was allowed little to no influence over Japan. This foreign presence marks the only time in Japan's history that it has been occupied by a foreign power.[1] At MacArthur's insistence, Emperor Hirohito remained on the imperial throne. The wartime cabinet was replaced with a cabinet acceptable to the Allies and committed to implementing the terms of the Potsdam Declaration, which among other things called for the country to become a parliamentary democracy. Under MacArthur's guidance, the Japanese government introduced sweeping social reforms and implemented economic reforms that recalled American "New Deal" priorities of the 1930s under President Roosevelt.[2] The Japanese constitution was comprehensively overhauled and the Emperor's theoretically-vast powers, which for many centuries had been constrained by conventions that had evolved over time, became strictly limited by law. The occupation, codenamed Operation Blacklist,[3] was ended by the San Francisco Peace Treaty, signed on September 8, 1951, and effective from April 28, 1952, after which Japan's sovereignty – with the exception, until 1972, of the Ryukyu Islands – was fully restored.

Empire of Japan (1945–1947) 大日本帝國 Dai Nippon Teikoku Japan (1947–1952) 日本国 Nippon-koku | |

|---|---|

| 1945–1952 | |

Imperial Seal

| |

Map of Japan under Allied occupation

| |

| Status | Military occupation |

| Capital | Tokyo |

| Common languages | Japanese |

| Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers | |

• 1945–1951 | GEN Douglas MacArthur |

• 1951–1952 | GEN Matthew Ridgway |

| Emperor | |

• 1945–1952 | Hirohito |

| Historical era | Shōwa period (Cold War) |

| August 14, 1945 | |

• Occupation begins | August 28 1945 |

• Instrument of Surrender signed | September 2, 1945 |

| October 25, 1945 | |

| August 15, 1948 | |

| September 9, 1948 | |

| April 28 1952 | |

| Today part of | Countries

today

|

| |

| History of Japan |

|---|

|

Japanese surrender

Initial phase

Japan surrendered to the Allies on August 15, 1945, when the Japanese government notified the Allies that it had accepted the Potsdam Declaration. On the following day, Emperor Hirohito announced Japan's unconditional surrender on the radio (the Gyokuon-hōsō). The announcement was the emperor's first ever planned radio broadcast and the first time most citizens of Japan ever heard their sovereign's voice.[4] This date is known as Victory over Japan, or V-J Day, and marked the end of World War II and the beginning of a long road to recovery for a shattered Japan. Japanese officials left for Manila, Philippines on August 19 to meet MacArthur and to discuss surrender terms. On August 28, 1945, 150 US personnel flew to Atsugi, Kanagawa Prefecture. They were followed by USS Missouri,[5] whose accompanying vessels landed the 4th Marine Regiment on the southern coast of Kanagawa. The 11th Airborne Division was airlifted from Okinawa to Atsugi Airdrome, 50 kilometres (30 mi) from Tokyo. Other Allied personnel followed.

MacArthur arrived in Tokyo on August 30, and immediately decreed several laws. No Allied personnel were to assault Japanese people. No Allied personnel were to eat the scarce Japanese food. Flying the Hinomaru or "Rising Sun" flag was initially severely restricted (although individuals and prefectural offices could apply for permission to fly it). This restriction was partially lifted in 1948 and completely lifted the following year.[6]

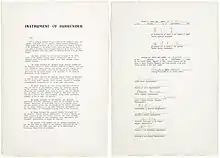

On September 2, 1945, Japan formally surrendered with the signing of the Japanese Instrument of Surrender. On September 6, US President Truman approved a document titled "US Initial Post-Surrender Policy for Japan".[7] The document set two main objectives for the occupation: (1) eliminating Japan's war potential and (2) turning Japan into a democratic-style nation with pro-United Nations orientation. Allied (primarily American) forces were set up to supervise the country, and "for eighty months following its surrender in 1945, Japan was at the mercy of an army of occupation, its people subject to foreign military control."[8] At the head of the Occupation administration was General MacArthur, who was technically supposed to defer to an advisory council set up by the Allied powers, but in practice did not and did everything himself. As a result, this period was one of significant American influence, described near the end of the occupation in 1951 that "for six years the United States has had a freer hand to experiment with Japan than any other country in Asia, or indeed in the entire world."[9] Looking back to his work among the Japanese, MacArthur said, "Measured by the standards of modern civilization, they would be like a boy of twelve" compared to the maturity of the US and Germany, and had a good chance of putting away their troubled past.[10]

SCAP

On V-J Day, US President Harry Truman appointed General Douglas MacArthur as Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP), to supervise the occupation of Japan. During the war, the Allied Powers had planned to divide Japan amongst themselves for the purposes of occupation, as was done for the occupation of Germany. Under the final plan, however, SCAP was given direct control over the main islands of Japan (Honshu, Hokkaido, Shikoku, and Kyushu) and the immediately surrounding islands, while outlying possessions were divided between the Allied Powers as follows:

- Soviet Union: North Korea (not a full occupation), South Sakhalin, and the Kuril Islands

- United States: South Korea (not a full occupation), Okinawa, the Amami Islands, the Ogasawara Islands and Japanese possessions in Micronesia

- China: Taiwan and Penghu

It is unclear why the occupation plan was changed. Common theories include the increased power of the United States following development of the atomic bomb, Truman's greater distrust of the Soviet Union when compared with Roosevelt, and an increased desire to restrict Soviet influence in East Asia after the Yalta Conference.

The Soviet Union had some intentions of occupying Hokkaidō.[11] Had this occurred, there might have eventually been a communist state in the Soviet zone of occupation. However, unlike the Soviet occupations of East Germany and North Korea, these plans were frustrated by Truman's opposition.[11]

MacArthur's first priority was to set up a food distribution network; following the collapse of the ruling government and the wholesale destruction of most major cities, virtually everyone was starving. Even with these measures, millions of people were still on the brink of starvation for several years after the surrender.[12] As expressed by Kawai Kazuo, "Democracy cannot be taught to a starving people".[13] The US government encouraged democratic reform in Japan, and while it sent billions of dollars in food aid, this was dwarfed by the occupation costs it imposed on the struggling Japanese administration.[14][15]

Initially, the US government provided emergency food relief through Government Aid and Relief in Occupied Areas (GARIOA) funds. In fiscal year 1946, this aid amounted to US$92 million in loans. From April 1946, in the guise of Licensed Agencies for Relief in Asia, private relief organizations were also permitted to provide relief. Once the food network was in place MacArthur set out to win the support of Hirohito. The two men met for the first time on September 27; the photograph of the two together is one of the most famous in Japanese history. Some were shocked that MacArthur wore his standard duty uniform with no tie instead of his dress uniform when meeting the emperor. With the sanction of Japan's reigning monarch, MacArthur had the political ammunition he needed to begin the real work of the occupation. While other Allied political and military leaders pushed for Hirohito to be tried as a war criminal, MacArthur resisted such calls, arguing that any such prosecution would be overwhelmingly unpopular with the Japanese people. He also rejected the claims of members of the imperial family such as Prince Mikasa and Prince Higashikuni and demands of intellectuals like Tatsuji Miyoshi, who sought the emperor's abdication.[16]

By the end of 1945, more than 350,000 US personnel were stationed throughout Japan. By the beginning of 1946, replacement troops began to arrive in the country in large numbers and were assigned to MacArthur's Eighth Army, headquartered in Tokyo's Dai-Ichi building. Of the main Japanese islands, Kyūshū was occupied by the 24th Infantry Division, with some responsibility for Shikoku. Honshu was occupied by the First Cavalry Division. Hokkaido was occupied by the 11th Airborne Division.

By June 1950, all these army units had suffered extensive troop reductions and their combat effectiveness was seriously weakened. When North Korea invaded South Korea in the Korean War, elements of the 24th Division were flown into South Korea to try to fight the invasion force there, but the inexperienced occupation troops, while acquitting themselves well when suddenly thrown into combat almost overnight, suffered heavy casualties and were forced into retreat until other Japan occupation troops could be sent to assist.

Organizations running in parallel to SCAP

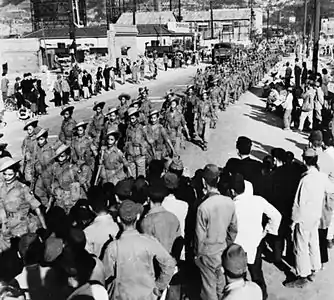

The official British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF), composed of Australian, British, Indian and New Zealand personnel, was deployed on February 21, 1946. While US forces were responsible for the overall occupation, BCOF was responsible for supervising demilitarization and the disposal of Japan's war industries.[17] BCOF was also responsible for occupation of several western prefectures and had its headquarters at Kure. At its peak, the force numbered about 40,000 personnel. During 1947, BCOF began to decrease its activities in Japan, and officially wound up in 1951.

The Far Eastern Commission and Allied Council for Japan were also established to supervise the occupation of Japan.[18] The establishment of a multilateral Allied council for Japan was proposed by the Soviet government as early as September 1945, and was supported partially by the British, French and Chinese governments.[19]

Outcomes

Disarmament

Japan's postwar constitution, adopted under Allied supervision, included a "Peace Clause", Article 9, which renounced war and banned Japan from maintaining any armed forces. This clause was not imposed by the Allies: rather, it was the work of the Japanese government itself, and according to most sources, was the work of Prime Minister Kijūrō Shidehara.[20][21] The clause was intended to prevent the country from ever becoming an aggressive military power again. However, the United States was soon pressuring Japan to rebuild its army as a bulwark against communism in Asia after the Chinese Civil War and the Korean War. During the Korean War, US forces largely withdrew from Japan to redeploy to South Korea, leaving the country almost totally defenseless. As a result, a new National Police Reserve armed with military-grade weaponry was created. In 1954, the Japan Self-Defense Forces were founded as a full-scale military in all but name. To avoid breaking the constitutional prohibition on military force, they were officially founded as an extension to the police force. Traditionally, Japan's military spending has been restricted to about 1% of its gross national product, though this is by popular practice, not law, and has fluctuated up and down from this figure. Prime Ministers Junichiro Koizumi and Shinzo Abe, among others, have tried to repeal or amend the clause. The JSDF slowly grew to considerable strength, and Japan now has the eighth largest military budget in the world.[22]

Liberalization

All the major sectors of the Japanese society, government, and economy were liberalized in the first few years and won strong support from liberals in Japan.[23] Historians emphasize the similarity to the American New Deal programs of the 1930s.[24] Moore and Robinson note that, "New Deal liberalism seemed natural, even to conservative Republicans such as MacArthur and Whitney."[25] The issuing of the Removal of Restrictions on Political, Civil, and Religious Liberties directive by SCAP on October 4, 1945, led to the abolition of the Peace Preservation Law and the release of all political prisoners.[26][27]

The electric utilities were privatized into nine regional privately owned government-granted monopolies in 1951, creating companies such as the Tokyo Electric Power Company. The privatization was inspired by the then mostly regulated electricity sector in the United States.

Emphasis on stability and economic growth

From late 1947, US priorities shifted to internal political stability and economic growth. Economic deconcentration, for example, was left uncompleted as GHQ responded to new imperatives. American authorities encouraged business practices and industrial policies that have since become sources of contention between Japan and its major trade partners, notably the United States.[28] During the occupation, GHQ/SCAP mostly abolished many of the financial coalitions known as the Zaibatsu, which had previously monopolized industry.[29] Along with the later American change of heart, and due in part to the need for an economically stronger Japan in the face of a perceived Soviet threat, these economic reforms were also hampered by the wealthy and influential Japanese who stood to lose a great deal. As such, there were those who consequently resisted any attempts at reform, claiming that the zaibatsu were required for Japan to compete internationally, and looser industrial groupings known as keiretsu evolved. A major land reform was also conducted, led by Wolf Ladejinsky of General Douglas MacArthur's SCAP staff. However, Ladejinsky has stated that the real architect of reform was Hiro'o Wada, former Japanese Minister of Agriculture.[30] Between 1947 and 1949, approximately 5,800,000 acres (23,000 km2) of land (approximately 38% of Japan's cultivated land) were purchased from the landlords under the government's reform program and resold at extremely low prices (after inflation) to the farmers who worked them. By 1950, three million peasants had acquired land, dismantling a power structure that the landlords had long dominated.[31]

Democratization

In 1946, the Diet ratified a new Constitution of Japan that followed closely a "model copy" prepared by the GHQ/SCAP,[32] and was promulgated as an amendment to the old Prussian-style Meiji Constitution. The new constitution drafted by Americans allowed access and control over the Japanese military through MacArthur and the Allied occupation on Japan.[33] "The political project drew much of its inspiration from the U.S. Bill of Rights, New Deal social legislation, the liberal constitutions of several European states and even the Soviet Union.... (It) transferred sovereignty from the Emperor to the people in an attempt to depoliticize the Throne and reduce it to the status of a state symbol. The hereditary peerage kazoku were abolished in 1947.[34] Included in the revised charter was the famous "no war", "no arms" Article Nine, which outlawed belligerency as an instrument of state policy and the maintenance of a standing army. The 1947 Constitution also enfranchised women, guaranteed fundamental human rights, strengthened the powers of Parliament and the Cabinet, and decentralized the police and local government."[35] One example of MacArthur's push towards democratization implemented the land reform and redistribution of ownership within the agricultural system.[36] The land reform was established in order to improve not only the economy but the welfare of farmers as well.[37] MacArthur's land reform policy redistribution resulted in only 10% of the land being worked by non-owners.[36] On December 15, 1945, the Shinto Directive was issued, abolishing Shinto as a state religion and prohibiting some of its teachings and rites that were deemed to be militaristic or ultra-nationalistic. On April 10, 1946, an election with 78.52% voter turnout among men and 66.97% among women[38] gave Japan its first modern prime minister, Shigeru Yoshida.

Trade Union Act

In 1945 the Diet passed Japan's first ever trade union law protecting the rights of workers to form or join a union, to organize, and take industrial action. There had been pre-war attempts to do so, but none that were successfully passed until the Allied occupation.[39] A new Trade Union Law was passed on June 1, 1949, which remains in place to the present day. According to Article 1 of the Act, the purpose of the act is to "elevate the status of workers by promoting their being on equal standing with the employer".[40]

Labor Standards Act

The Labor Standards Act was enacted on April 7, 1947, to govern working conditions in Japan. According to Article 1 of the Act, its goal is to ensure that "Working conditions shall be those which should meet the needs of workers who live lives worthy of human beings."[41] Support stemming from the Allied occupation has introduced better working conditions and pay for numerous employees in Japanese business.[36] This allowed for more sanitary and hygienic working environments along with welfare and government assistance for health insurance, pensions plans and work involving other trained specialists.[36] While it was created while Japan was under occupation, the origins of the Act have nothing to do with the occupation forces. It appears to have been the brainchild of Kosaku Teramoto, a former member of the Thought Police, who had become the head of the Labor Standards section of the Welfare Ministry.[42]

Education reform

Before and during the war, Japanese education was based on the German system, with "Gymnasien" (selective grammar schools) and universities to train students after primary school. During the occupation, Japan's secondary education system was changed to incorporate three-year junior high schools and senior high schools similar to those in the US: junior high school became compulsory but senior high school remained optional. The Imperial Rescript on Education was repealed, and the Imperial University system reorganized. The longstanding issue of Japanese script reform, which had been planned for decades but continuously opposed by more conservative elements, was also resolved during this time. The Japanese written system was drastically reorganized with the Tōyō kanji-list in 1946, predecessor of today's Jōyō kanji, and orthography was greatly altered to reflect spoken usage.

Release of political prisoners

On October 4, 1945, the GHQ issued the Removal of Restrictions on Political, Civil, and Religious Liberties directive. The directive ordered the release of political prisoners.[43]

Impact

War criminals

While these other reforms were taking place, various military tribunals, most notably the International Military Tribunal for the Far East in Ichigaya, were trying Japan's war criminals and sentencing many to death and imprisonment. However, many suspects such as Masanobu Tsuji, Nobusuke Kishi, Yoshio Kodama and Ryōichi Sasakawa were never judged, while the Emperor Hirohito, all members of the imperial family implicated in the war such as Prince Chichibu, Prince Yasuhiko Asaka, Prince Fushimi Hiroyasu, Prince Naruhiko Higashikuni and Prince Tsuneyoshi Takeda, and all members of Unit 731—including its director Dr. Shirō Ishii—were granted immunity from criminal prosecution by General MacArthur.

Before the war crimes trials actually convened, the SCAP, its International Prosecution Section (IPS) and Shōwa officials worked behind the scenes not only to prevent the imperial family from being indicted, but also to slant the testimony of the defendants to ensure that no one implicated the Emperor. High officials in court circles and the Shōwa government collaborated with Allied GHQ in compiling lists of prospective war criminals, while the individuals arrested as Class A suspects and incarcerated in Sugamo prison solemnly vowed to protect their sovereign against any possible taint of war responsibility.[44] Thus, months before the Tokyo tribunal commenced, MacArthur's highest subordinates were working to attribute ultimate responsibility for Pearl Harbor to Hideki Tojo[45] by allowing "the major criminal suspects to coordinate their stories so that the Emperor would be spared from indictment."[46] and "with the full support of MacArthur's headquarters, the prosecution functioned, in effect, as a defense team for the emperor."[47]

For historian John W. Dower,

Even Japanese peace activists who endorse the ideals of the Nuremberg and Tokyo charters, and who have labored to document and publicize Japanese atrocities, cannot defend the American decision to exonerate the emperor of war responsibility and then, in the chill of Cold war, release and soon afterwards openly embrace accused right-wing war criminals like the later prime minister Kishi Nobusuke.[48] In retrospect, apart from the military officer corps, the purge of alleged militarists and ultranationalists that was conducted under the Occupation had relatively small impact on the long-term composition of men of influence in the public and private sectors. The purge initially brought new blood into the political parties, but this was offset by the return of huge numbers of formally purged conservative politicians to national as well as local politics in the early 1950s. In the bureaucracy, the purge was negligible from the outset.... In the economic sector, the purge similarly was only mildly disruptive, affecting less than sixteen hundred individuals spread among some four hundred companies. Everywhere one looks, the corridors of power in postwar Japan are crowded with men whose talents had already been recognized during the war years, and who found the same talents highly prized in the "new" Japan.[49]

Rape

According to various accounts, U.S. troops committed thousands of rapes among the population of the Ryukyu Islands during the Okinawa Campaign and the beginning of the American occupation in 1945.[50][51]

Many Japanese civilians in the Japanese mainland feared that the Allied occupation troops were likely to rape Japanese women. The Japanese authorities set up a large system of prostitution facilities (Recreation and Amusement Association, or the RAA) in order to protect the population. According to John W. Dower, precisely as the Japanese government had hoped when it created the prostitution facilities, while the RAA was in place "the incidence of rape remained relatively low given the huge size of the occupation force".[52]:130 However, there was a resulting large rise in venereal disease among the soldiers, which led MacArthur to close down the prostitution in early 1946.[53] The incidence of rape increased after the closure of the brothels, possibly eight-fold; Dower states that "According to one calculation the number of rapes and assaults on Japanese women amounted to around 40 daily while the RAA was in operation, and then rose to an average of 330 a day after it was terminated in early 1946."[54] Brian Walsh states that rape was uncommon and rare throughout the occupation, he also disputed that the calculated number of daily rapes or assault being much lower. The increase in crimes during the termination of RAA was short and brief, they quickly declined afterwards.[55] Michael S. Molasky states that while rape and other violent crime were widespread in naval ports like Yokosuka and Yokohama during the first few weeks of occupation, according to Japanese police reports and journalistic studies, the number of incidents declined shortly after and they were not common on mainland Japan throughout the rest of occupation.[56] Two weeks into the occupation, the Occupation administration began censoring all media. This included any mention of rape or other sensitive social issues.[57][58] Brian Walsh states that the number of rape was little during the occupation of Japan but acknolwedged there was a "brief crime wave" which includes criminals incidents of all types.[59]

According to Dower, "more than a few incidents" of assault and rape were never reported to the police.[60] According to Toshiyuki Tanaka, 76 cases of rape or rape-murder were reported on Okinawa during the first five years of occupation, but according to Tanaka this is "but the tip of the iceberg" as most of the rapes went unreported.[61]

Censorship

After the surrender of Japan in 1945, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers abolished all forms of censorship and controls on Freedom of Speech, which was also integrated into Article 21 of the 1947 Constitution of Japan. However, press censorship remained a reality in the post-war era, especially in matters of pornography, and in political matters deemed subversive by the American government during the occupation of Japan.

The Allied occupation forces suppressed news of criminal activities such as rape; on September 10, 1945, SCAP "issued press and pre-censorship codes outlawing the publication of all reports and statistics 'inimical to the objectives of the Occupation'."[62]

According to David M. Rosenfeld:

Not only did Occupation censorship forbid criticism of the United States or other Allied nations, but the mention of censorship itself was forbidden. This means, as Donald Keene observes, that for some producers of texts "the Occupation censorship was even more exasperating than Japanese military censorship had been because it insisted that all traces of censorship be concealed. This meant that articles had to be rewritten in full, rather than merely submitting XXs for the offending phrases."

— Donald Keene, quoted in Dawn to the West[63]

Industrial disarmament

To further remove Japan as a potential future threat to the United States, the Far Eastern Commission decided that Japan was to be partly de-industrialized. The necessary dismantling of Japanese industry was foreseen to have been achieved if Japanese standards of living had been reduced to those existing in Japan the period 1930–1934.[64][65] In the end, the adopted program of de-industrialization in Japan was implemented to a lesser degree than the similar U.S. "industrial disarmament" program in Germany.[64] In view of the cost to American taxpayers for emergency food aid to Japan, in April 1948 the Johnston Committee Report recommended that the economy of Japan should instead be reconstructed. The report included suggestions for reductions in war reparations, and a relaxation of the "economic deconcentration" policy. For the fiscal year of 1949 funds were moved from the GARIOA budget into an Economic Rehabilitation in Occupied Areas (EROA) programme, to be used for the import of materials needed for economic reconstruction.

Prostitution

With the acceptance of the Allied occupation authorities, the Japanese organized a brothel system for the benefit of the more than 300,000 occupation troops. "The strategy was, through the special work of experienced women, to create a breakwater to protect regular women and girls."

In December 1945, a senior officer with the Public Health and Welfare Division of the occupation's General Headquarters wrote regarding the typical prostitute: "The girl is impressed into contracting by the desperate financial straits of her parents and their urging, occasionally supplemented by her willingness to make such a sacrifice to help her family", he wrote. "It is the belief of our informants, however, that in urban districts the practice of enslaving girls, while much less prevalent than in the past, still exists. The worst victims ... were the women who, with no previous experience, answered the ads calling for 'Women of the New Japan'."

MacArthur issued an order, SCAPIN 642 (SCAP Instruction), on January 21 ending licensed brothels for being "in contravention of the ideals of democracy". Although SCAPIN 642 ended the RAA's operations, it did not affect "voluntary prostitution" by individuals. Ultimately, SCAP responded by making all brothels and other facilities offering prostitution off-limits to Allied personnel on March 25, 1946.[66] By November, the Japanese government had introduced the new akasen (赤線, "red-line") system in which prostitution was permissible only in certain designated areas.[67][68]

Expulsions

The surrender of Imperial Japan meant reversal of its previous annexations—Manchuria (Manchukuo as a puppet regime under Japan) was to be returned to China (northern Manchuria partially occupied by the Soviets until 1955 when they turned over all their occupied territories there to the communist People's Republic of China), while Korea was officially given independence but came under a temporary division and joint occupation (as initially agreed) by the United States and Soviet Union. While the joint occupation ended before 1950, the division of the Korean peninsula was to remain permanent until today after the formations of Soviet-backed North Korea and US-supported South Korea and the subsequent war between the two countries from 1950 to 1953.

The Soviet Union claimed South Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands, with 400,000 Japanese fleeing or being expelled post-WWII. Similar actions happened in Taiwan and Manchuria after their return to China, with at least another million Japanese leaving mainland China itself, while Korea saw the flight of over 800,000 Japanese settlers from both the Soviet occupation sector in the north and the US occupation zone in the south. In all, Japanese repatriation centers handled over 7 million expatriates returning to the Japanese main islands.[69] Other areas where the Japanese were massively repatriated were from territories in the Pacific they previously occupied, including Guam and Saipan, and former colonial areas in Southeast Asia, such as Malaya and Indonesia.

Soviet activity

In a bid to occupy as much Japanese territory as possible, Soviet troops continued offensive military operations after the Japanese surrender, causing large-scale civilian casualties.[70] Such operations included the final battles on the Kuril Islands and South Sakhalin well past the end of August in 1945. In the end, despite its initial plan, the Soviet Union did not manage to occupy any part of the Japanese Home Islands, partly due to significant US opposition and Stalin's greater interest in establishing Soviet communist influence in Europe rather than in Asia.

Politics

Unlike the case in Germany, Japan retained a native government throughout the occupation. Although MacArthur's official staff history of the occupation referred to "the Eighth Army Military Government System", it explained that while "In Germany, with the collapse of the Nazi regime, all government agencies disintegrated, or had to be purged", the Japanese retained an "integrated, responsible government and it continued to function almost intact":[71]

In effect, there was no "military government" in Japan in the literal sense of the word. It was simply a SCAP superstructure over already existing government machinery, designed to observe and assist the Japanese along the new democratic channels of administration.

General Horace Robertson of Australia, head of BCOF, wrote:[72]

MacArthur at no time established in Japan what could be correctly described as Military government. He continued to use the Japanese government to control the country, but teams of military personnel, afterward replaced to quite a considerable extent by civilians, were placed throughout the Japanese prefectures as a check on the extent to which the prefectures were carrying out the directives issued by MacArthur’s headquarters or the orders from the central government.

The really important duty of the so called Military government teams was, however, the supervision of the issue throughout Japan of the large quantities of food stuffs and medical stores being poured into the country from American sources. The teams also contained so-called experts on health, education, sanitation, agriculture and the like, to help the Japanese in adopting more up to date methods sponsored by SCAP’s headquarters. The normal duties of a military government organisation, the most important of which are law and order and a legal system, were never needed in Japan since the Japanese government’s normal legal system still functioned with regard to all Japanese nationals ... The so-called military government in Japan was therefore neither military nor government.

The Japanese government's de facto authority was strictly limited at first, however, and senior figures in the government such as the Prime Minister effectively served at the pleasure of the occupation authorities before the first post-war elections were held. Political parties had begun to revive almost immediately after the occupation began. Left-wing organizations, such as the Japan Socialist Party and the Japan Communist Party, quickly reestablished themselves, as did various conservative parties. The old Seiyukai and Rikken Minseito came back as, respectively, the Liberal Party (Nihon Jiyuto) and the Japan Progressive Party (Nihon Shimpoto). The first postwar elections were held in 1946 (women were given the franchise for the first time), and the Liberal Party's vice president, Yoshida Shigeru (1878–1967), became prime minister. For the 1947 elections, anti-Yoshida forces left the Liberal Party and joined forces with the Progressive Party to establish the new Japan Democratic Party (Minshuto). This divisiveness in conservative ranks gave a plurality to the Japan Socialist Party, which was allowed to form a cabinet, which lasted less than a year. Thereafter, the socialist party steadily declined in its electoral successes. After a short period of Democratic Party administration, Yoshida returned in late 1948 and continued to serve as prime minister until 1954.

Japanese American contribution

Japan accepted the terms of the Potsdam Declaration and surrendered on August 15, 1945. Over 5,000 Japanese Americans served in the occupation of Japan.[73] Dozens of Japanese Americans served as translators, interpreters, and investigators in the International Military Tribunal for the Far East. Thomas Sakamoto served as press escort during the occupation of Japan. He escorted American correspondents to Hiroshima, and the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay. Sakamoto was one of three Japanese Americans to be on board the USS Missouri when the Japanese formally surrendered. Arthur S. Komori served as personal interpreter for Brig. Gen. Elliot R. Thorpe. Kay Kitagawa served as personal interpreter of Fleet Admiral William Halsey Jr..[74] Kan Tagami served as personal interpreter-aide for General Douglas MacArthur.[75] Journalist Don Caswell was accompanied by a Japanese American interpreter to Fuchū Prison, where the Japanese government imprisoned communists Tokuda Kyuichi, Yoshio Shiga, and Shiro Mitamura.[76]

Japanese Americans in the OSS parachuted down into Japanese POW prison camps at Hankow, Mukden, Peiping and Hainan as interpreters on mercy missions to liberate American and other Allied prisoners.[77] Arthur T. Morimitsu was the only Military Intelligence Service member in the detachment commanded by Major Richard Irby and 1st Lt. Jeffrey Smith to observe the surrender ceremony of 60,000 Japanese troops under Gen. Shimada.[78] Kan Tagami witnessed Japanese forces surrender to the British in Malaya.[75]

End of the occupation

In 1949, MacArthur made a sweeping change in the SCAP power structure that greatly increased the power of Japan's native rulers, and the occupation began to draw to a close. The Treaty of San Francisco, which was to end the occupation, was signed on September 8, 1951. It came into effect on April 28, 1952, formally ending all occupation powers of the Allied forces and restoring full sovereignty to Japan, except for the island chains of Iwo Jima and Okinawa, which the United States continued to hold. Iwo Jima was returned to Japan in 1968, and most of Okinawa was returned in 1972.

Following the American departure, Japan gained military protection from the United States. But the United States soon pressured Japan to rebuild its military capabilities, and as a result, the Japan Self-Defense Forces were formed as a de facto military force with US assistance. After the Yoshida Doctrine, Japan continued to prioritize economic growth over defense spending, relying on American protection to ensure it could focus mainly on economic recovery. Through Guided Capitalism, Japan was able to use its resources to economically recover from the war and revive industry.[79] Some 31,000 US military personnel remain in Japan today at Japanese government's invitation as the United States Forces Japan, under the terms of the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan (1960), not as an occupying force. US bases in and around Tokyo, Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Aomori, Sapporo, and Ishikari are active.

Criticism

On the day the occupation of Japan was over, the Asahi Shimbun published a very critical essay on the occupation, calling it "almost akin to colonialism" and claiming it turned the Japanese population "irresponsible, obsequious and listless... unable to perceive issues in a forthright manner, which led to distorted perspectives".[80] The purpose for delaying the return of the Japanese southern islands, the Bonin Islands including Chichi Jima, Okinawa, and the Volcano Islands including Iwo Jima to civil administration was the U.S. military's requirement to covertly base U.S. atomic weapons or their components on the islands where the presence or expansion of U.S. bases remain a heated controversy to this day.

In later years, General MacArthur himself thought little of the Occupation. In June 1960, he was decorated by the Japanese government with the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun with Paulownia Flowers, the highest Japanese order which may be conferred on an individual who is not a head of state. In his statement upon receiving the honor, MacArthur expressed his "own firm disbelief in the usefulness of military occupations with their corresponding displacement of civil control."[81]

Cultural reaction

Hirohito's surrender broadcast was a profound shock to Japanese citizens. After years of being told about Japan's military might and the inevitability of victory, these beliefs were proven false in the space of a few minutes. But for many people, these were only secondary concerns since they were also facing starvation and homelessness.

Post-war Japan was chaotic. The air raids on Japan's urban centers left millions displaced and food shortages, created by bad harvests and the demands of the war, worsened when the seizure of food from Korea, Taiwan, and China ceased.[82] Repatriation of Japanese living in other parts of Asia and hundreds of thousands of demobilized prisoners of war only aggravated the problems in Japan as these people put more strain on already scarce resources. Over 5.1 million Japanese returned to Japan in the fifteen months following October 1, 1945, and another million returned in 1947.[83] Alcohol and drug abuse became major problems. Deep exhaustion, declining morale and despair were so widespread that it was termed the "kyodatsu condition" (虚脱状態, kyodatsujoutai, lit. "state of lethargy").[84] Inflation was rampant and many people turned to the black market for even the most basic goods. These black markets in turn were often places of turf wars between rival gangs, like the Shibuya incident in 1946. Prostitution also increased considerably.

In the 1950s, kasutori culture emerged. In response to the scarcity of the previous years, this sub-culture, named after the preferred drink of the artists and writers who imbibed it, emphasized escapism, entertainment and decadence.[85]

The phrase "shikata ga nai", or "nothing can be done about it," was commonly used in both Japanese and American press to encapsulate the Japanese public's resignation to the harsh conditions endured while under occupation. However, not everyone reacted the same way to the hardships of the postwar period. While some succumbed to the difficulties, many more were resilient. As the country regained its footing, they were able to bounce back as well.

Leftists looked upon the occupation forces as a "liberation army".[86]

Japanese women

It has been argued that the granting of rights to women played an important role in the radical shift Japan underwent from a war nation to a democratized and demilitarized country.[87] In the first postwar general elections of 1946, over a third of the votes were cast by women. This unexpectedly high female voter turnout led to the election of 39 female candidates, and the increasing presence of women in politics was perceived by Americans as evidence of an improvement of Japanese women's condition.[88]

American feminists saw Japanese women as victims of feudalistic and chauvinistic traditions that had to be broken by the Occupation. American women assumed a central role in the reforms that affected the lives of Japanese women: they educated Japanese about Western ideals of democracy, and it was an American woman, Beate Sirota, who wrote the articles guaranteeing equality between men and women for the new constitution.[89] General Douglas MacArthur did not mean for Japanese women to give up their central role in the home as wives and mothers, but rather that they could now assume other roles simultaneously, such as that of worker.[90][91]

In 1953, journalist Ichirō Narumigi commented that Japan had received "liberation of sex" along with the "four presents" that it had been granted by the occupation (respect for human rights, gender equality, freedom of speech, and women's enfranchisement).[92] Indeed, the occupation also had a great impact on relationships between men and women in Japan. The "modern girl" phenomenon of the 1920s and early 1930s had been characterized by greater sexual freedom, but despite this, sex was usually not perceived as a source of pleasure (for women) in Japan. Westerners, as a result, were thought to be promiscuous and sexually deviant.[93] The sexual liberation of European and North American women during World War II was unthinkable in Japan, especially during wartime where rejection of Western ways of life was encouraged.[94]

The Japanese public was thus astounded by the sight of some 45,000 so-called "pan pan girls" (prostitutes) fraternizing with American soldiers during the occupation.[92] In 1946, the 200 wives of US officers landing in Japan to visit their husbands also had a similar impact when many of these reunited couples were seen walking hand in hand and kissing in public.[95] Both prostitution and marks of affection had been hidden from the public until then, and this "democratization of eroticism" was a source of surprise, curiosity, and even envy. The occupation set new models for relationships between Japanese men and women: the western practice of "dating" spread, and activities such as dancing, movies and coffee were not limited to "pan pan girls" and American troops anymore, and became popular among young Japanese couples.[96]

See also

References

Citations

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art. "Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History: Japan, 1900 a.d.–present". Archived from the original on 2009-06-18. Retrieved 2009-02-01.

- Theodore Cohen, and Herbert Passin, Remaking Japan: The American Occupation as New Deal (Free Press, 1987).

- Takemae, E. (2003). The Allied Occupation of Japan. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 9780826415219.

- Gordon 2003, p. 226

- Video: Allied Forces Land In Japan (1945). Universal Newsreel. 1945. Archived from the original on February 25, 2012. Retrieved February 21, 2012.

- text in Department of State Bulletin, September 23, 1945, pp. 423–427.

- Takemae, Eiji. 2002 p. xxvi.

- Kawai 1951, p. 23

- Hunt, M. H. (2015). The world transformed: 1945 to the present : a documentary reader. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's. p. 86-87.

- Hasegawa 2005, 271ff.

- Gordon 2003, p. 228

- Kawai 1951, p. 27

- Kawai 1951, p. 26

- Eiji Takemae (2003). Allied Occupation of Japan. A&C Black. pp. 126–. ISBN 978-0-8264-1521-9.

- Bix 2001, pp. 571–573

- "British Commonwealth Occupation Force 1945–52". awm.gov.au. Archived from the original on 2008-08-20. Retrieved 2004-11-26.

- National Diet Library: Glossary and Abbreviations Archived 2006-11-15 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Memorandum by the Soviet Delegation to the Council of Foreign Ministers, Sept. 24, 1945". Archived from the original on 2016-05-31. Retrieved 2016-04-22.

- Douglas MacArthur, Reminiscences (1964), p. 302.

- Klaus Schlichtmann, JAPAN IN THE WORLD. Shidehara Kijűrô, Pacifism and the Abolition of War, Lanham, Boulder, New York, Toronto etc., 2 vols., Lexington Books, 2009. See also, by the same author, 'A Statesman for The Twenty-First Century? The Life and Diplomacy of Shidehara Kijûrô (1872–1951)', Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan, fourth series, vol. 10 (1995), pp. 33–67

- "Japan's About-Face ~ Introduction - Wide Angle - PBS". pbs.org. Archived from the original on 2013-06-15. Retrieved 2017-09-07.

- Eiji Takemae (2003). Allied Occupation of Japan. A&C Black. p. 241. Archived from the original on 2016-01-02. Retrieved 2015-10-18.

- Theodore Cohen and Herbert Passin, Remaking Japan: The American Occupation as New Deal (1987)

- Ray A. Moore and Donald L. Robinson, Partners for democracy: Crafting the new Japanese state under Macarthur (Oxford University Press, 2004) p 98

- "5-3 The Occupation and the Beginning of Reform - Modern Japan in archives". Modern Japan in Archives. National Diet Library. Archived from the original on 22 January 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- "Glossary and Abbreviations". Birth of the Constitution of Japan. National Diet Library. Archived from the original on 20 January 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- Takemae, Eiji. 2002 p. xli.

- Schaller 1985, p. 25

- Ness 1967, p. 819

- Flores 1970, p. 901

- Takemae, Eiji 2002, p. xxxvii.

- Hunt, Michael (2013). The World Transformed:1945 to the Present. Oxford University Press. p. 86. ISBN 9780199371020.

- "Kazoku - Japanese nobility". ncyclopaedia Britannica. Dec 21, 2016. Archived from the original on August 31, 2019.

- Takemae, Eiji 2002, p. xxxix.

- Hunt, Michael (2013). The World Transformed:1945 to the Present. Oxford University Press. pp. 86–87.

- Hunt, Michael (2013). The World Transformed:1945 to the Present. Oxford University Press. p. 81.

- Asahi Shimbun Staff 1972, p. 126.

- Kimura, Shinichi, Unfair Labor Practices under the Trade Union Law of Japan Archived 2011-07-18 at the Wayback Machine

- Japan Institute for Labor Policy and Training Trade Union Law Archived 2011-06-12 at the Wayback Machine

- Japan Institute for Labor Policy and Training Labor Standards Act Archived 2011-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Dower, John. Embracing Defeat. Penguin, 1999. ISBN 978-0-14-028551-2. p. 246.

- "5-3 The Occupation and the Beginning of Reform – Modern Japan in archives". National Diet Library. Archived from the original on 22 January 2015. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- Dower 1999, p. 325.

- Bix 2001, p. 585

- Bix 2001, p. 583

- Dower 1999, p. 326.

- Dower 1999, p. 562.

- Dower 1993, p. 11

- Feifer, George, The Battle of Okinawa : the blood and the bomb, p. 373.

- Schrijvers, Peter, The GI war against Japan : American soldiers in Asia and the Pacific during World War II, p. 212.

- Dower 1999

- Dower 1999, pp. 130.

- Dower 1999, pp. 579.

- Walsh, Brian (October 2018). "Sexual Violence During the Occupation of Japan". The Journal of Military History. 82 (4): 1199–1230.

- Molasky, Michael. The American occupation of Japan and Okinawa: Literature and Memory Archived 2016-01-02 at the Wayback Machine, Routledge, 1999, p. 121. ISBN 0-415-19194-7.

- Svoboda, Terèse (May 23, 2009), "U.S. Courts-Martial in Occupation Japan: Rape, Race, and Censorship", The Asia-Pacific Journal, 21-1-09, archived from the original on January 29, 2012, retrieved January 30, 2012.

- Dower 1999, pp. 412.

- Walsh 2018, p. 1220.

- Dower 1999, pp. 211.

- Tanaka, Toshiyuki. Japan's Comfort Women: Sexual Slavery and Prostitution During World War II Archived 2016-01-02 at the Wayback Machine, Routledge, 2003, p. 112. ISBN 0-203-30275-3.

- Eiji Takemae, Robert Ricketts, Sebastian Swann, Inside GHQ: The Allied Occupation of Japan and Its Legacy. p. 67. (Google.books Archived 2016-01-02 at the Wayback Machine)

- David M. Rosenfeld, Dawn to the West, New York: Henry Holt, 1984), p. 967, quoting from Donald Keene in Unhappy Soldier: Hino Ashihei and Japanese World War II Literature Archived 2016-05-17 at the Wayback Machine, p. 86.

- Frederick H. Gareau "Morgenthau's Plan for Industrial Disarmament in Germany" The Western Political Quarterly, Vol. 14, No. 2 (Jun., 1961), pp. 531.

- (Note: A footnote in Gareau also states: "For a text of this decision, see Activities of the Far Eastern Commission. Report of the Secretary General, February, 1946 to July 10, 1947, Appendix 30, p. 85.")

- Tanaka 2002, p. 162

- Lie 1997, p. 258

- Kristof, Nicholas D. (October 27, 1995). "Fearing G.I. Occupiers, Japan Urgesd Women Into Brothels". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 16, 2008. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- Lori Watt (2010). When Empire Comes Home: Repatriation and Reintegration in Postwar Japan. Harvard University Press. pp. 65–72. Archived from the original on 2016-01-02. Retrieved 2015-10-18.

- "History News Network - As World War II entered its final stages the belligerent powers committed one heinous act after another". hnn.us. Archived from the original on 2008-12-16. Retrieved 2008-07-19.

- Reports of General MacArthur / MacArthur in Japan: The Occupation: Military Phase. Center for Military History, United States Army. 1950. pp. 193–194. Archived from the original on 2013-11-10. Retrieved 2013-10-15.

- Wood, James. "The Australian Military Contribution to the Occupation of Japan, 1945–1952" (PDF). Australian War Museum. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-11-04. Retrieved August 12, 2012.

- "The Nisei Intelligence War Against Japan by Ted Tsukiyama". Japanese American Veterans Association. Archived from the original on 2017-04-05.

- James C. McNaughton. Nisei linguists: Japanese Americans in the Military Intelligence Service During World War II. Government Printing Office. pp. 392–442.

- "NOTED NISEI VETERAN KAN TAGAMI PASSES. HELD UNPRECEDENTED ONE-ON-ONE PRIVATE MEETING WITH EMPEROR HIROHITO AT IMPERIAL PALACE. AKAKA PAYS HIGH TRIBUTE". Japanese American Veterans Association. Archived from the original on 2017-04-05.

- "Japanese Diet Called Farce". The Tuscaloosa News. 5 October 1945. Archived from the original on 9 April 2016. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- "Japanese American Veterans Association". Military Intelligence Service Research Center. Archived from the original on 2017-04-05.

- "Delayed Recognition in the CBI Theater: A Common Problem?". Japanese American Veterans Association. Archived from the original on 2017-03-22.

- Thomas, Vladimir (February 5, 2017). the world transformed 1945 to the present (Second ed.). Micheal H.Hunt. pp. 88, 89.

- "Japan's 'long-awaited spring'", Japan Times, April 28, 2002.

- General Macarthur Receives Japan's Highest Honour (video). British Pathe. June 1960. 2778.2. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- Dower 1999, p. 90.

- Dower 1999, p. 54.

- Gordon 2003, p. 229

- Dower 1999, p. 148.

- Richard B. Finn (1992). Winners in Peace: MacArthur, Yoshida, and Postwar Japan. University of California Press. pp. 112–114.

- Yoneyama, Lisa. "Liberation under Siege: U.S. Military Occupation and Japanese Women's Enfranchisement" American Quarterly, Vol. 57, No. 3 (Sept., 2005), pp. 887.

- Koikari, Mire. "Exporting Democracy? American Women, 'Feminist Reforms,' and Politics of Imperialism in the U.S. Occupation of Japan, 1945–1952," Frontier: A Journal of Women Studies, Vol. 23, No. 1 (2002), pp. 29.

- Koikari 2002, pp. 27–30

- Koikari 2002, p. 29

- McLelland, Mark. "'Kissing is a symbol of democracy!' Dating, Democracy, and Romance in Occupied Japan, 1945–1952" Journal of the History of Sexuality, Vol. 19, No. 3 (Sept., 2010), pp. 517.

- McLelland 2010, p. 518

- McLelland 2010, pp. 511–512

- McLelland 2010, p. 514

- McLelland 2010, p. 529

- McLelland 2010, pp. 519–520

Sources

- Asahi Shimbun Staff, The Pacific rivals; a Japanese view of Japanese-American relations, New York: Weatherhill, 1972. ISBN 978-0-8348-0070-0.

- Bix, Herbert. Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan. New York, NY: Harper Perennial, 2001. ISBN 0-06-093130-2.

- Cripps, D. "Flags and Fanfares: The Hinomaru Flag and the Kimigayo Anthem". In Goodman, Roger & Ian Neary, Case Studies on Human Rights in Japan. London: Routledge, 1996. pp. 76–108. ISBN 1-873410-35-2.

- Dower, John W. (1993), Japan in War and Peace, New York, NY: The New Press, ISBN 1-56584-067-4; ISBN 1-56584-279-0

- Dower, John W. (1999), Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II, Norton, ISBN 0-393-04686-9

- Feifer, George (2001). The Battle of Okinawa : the blood and the bomb. Guilford, CT: Lyons Press. ISBN 9781585742158.

- Flores, Edmundo. Issues of Land Reform. The Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 78, No. 4, Part 2: Key Problems of Economic Policy in Latin America. (Jul – Aug., 1970), pp. 890–905.

- Goodman, Roger & Kirsten Refsing. Ideology and Practice in Modern Japan London: Routledge, 1992. ISBN 0-415-06102-4.

- Gordon, Andrew (2003). A Modern History of Japan. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-511060-9.

- Guillain, Robert. I Saw Tokyo burning: An Eyewitness Narrative from Pearl Harbor to Hiroshima (J. Murray, 1981). ISBN 0-385-15701-0.

- Hasegawa, Tsuyoshi. Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-674-01693-9.

- Hood, Christopher Philip (2001). Japanese Education Reform: Nakasone's Legacy. New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group. ISBN 041523283X. OCLC 44885267.

- Kawai, Kazuo. "American influence on Japanese thinking" Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. Vol. 278, 1951: pp. 23–31.

- Ness, Gayl D. Review of the book Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World. American Sociological Review (1967), Volume 32, Number 5, pp. 818–820.

- Schaller, Michael. The American Occupation of Japan: the Origins of the Cold War in Asia. New York, Oxford University Press, 1985. ISBN 0195036263. OCLC 11971554.

- Schrijvers, Peter (2002). The GI war against Japan : American soldiers in Asia and the Pacific during World War II. New York, NY: New York University Press. ISBN 9780814798164.

- Sugita, Yoneyuki. Pitfall or Panacea: The Irony of US Power in Occupied Japan, 1945–1952 (Rutledge, 2003). ISBN 0-415-94752-9.

- Takemae, Eiji trans. and adpt. by Robert Ricketts and Sebastian Swann. Inside GHQ: The Allied Occupation of Japan and its Legacy. New York, Continuum, 2002. ISBN 0826462472. OCLC 45583413.

- Weisman, Steven R. (1990, April 29). "For Japanese, Flag and Anthem Sometimes Divide". The New York Times.

Further reading

- Aldous, Christopher, and Akihito Suzuki. Reforming Public Health in Occupied Japan, 1945–52: Alien Prescriptions? (Routledge, 2012) ISBN 978-0-203-14282-0

- Caprio, Mark E. & Yoneyuki Sugita (2007). Democracy in Occupied Japan: The U.S. Occupation and Japanese Politics and Society. Routledge.

- Hirano, Kyōko (1992). Mr. Smith Goes to Tokyo: The Japanese Cinema Under the American Occupation, 1945–1952. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 1-56098-157-1. OCLC 25367560.

- La Cerda, John. The Conqueror Comes to Tea: Japan under MacArthur. Rutgers University, 1946.

- Mark Gayn (Dec 15, 1989). Japan Diary. Tuttle Publishing.

- Richard B. Finn (1992). Winners in Peace: MacArthur, Yoshida, and Postwar Japan. University of California Press. pp. 112–114.

- Rinjirō Sodei; John Junkerman; Shizue Matsuda (Jan 1, 2006). Dear General MacArthur: Letters from the Japanese During the American Occupation. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 31–42.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Occupation of Japan. |

- American Occupation of Japan, Voices of the Key Participants in the Claremont Colleges Digital Library

- J.C.S 1380/15 BASIC DIRECTIVE FOR POST-SURRENDER MILITARY GOVERNMENT IN JAPAN PROPER

- RELATIONS BETWEEN ALLIED FORCES AND THE POPULATION OF JAPAN

- The Road Ahead: Lessons in Nation Building from Japan, Germany, and Afghanistan for Postwar Iraq, by Ray Salvatore Jennings May 2003, Peaceworks No. 49, United States Institute of Peace (The PDF report contains a chapter on the occupation policies.)

- Memories of War: The Second World War and Japanese Historical Memory in Comparative Perspective

- A sweet memory: My first encounter of an American soldier

- Hirata Tetsuo and John W. Dower, "Japan's Red Purge: Lessons from a Saga of Suppression of Free Speech and Thought"

- Zaibatsu Dissolution, Reparations and Administrative Guidance.

- "Four Jap Prisons Open Their Doors". Lawrence Journal-World. Oct 10, 1945.

- "Nippon Communists March Through Allied-Ruled Tokyo, Ask Removal of Jap Emperor". The Bulletin. Oct 10, 1945.

- "Japanese Wave Red Banners In Tokyo Parade". Ottawa Citizen. Oct 10, 1945.

- "REMOVE HIROHITO IS CRY OF FREED JAP COMMUNISTS". Toronto Daily Star. October 10, 1945.

- "JAPS. SAY SACK EMPEROR". Examiner. 12 October 1945.

- "AMAZED TOKIO PEOPLE SEE COMMUNIST MARCH". The Telegraph. 11 October 1945.

- "Communist Crowds Voice Imperial Rule Opposition; Nippons Band To Assail Reds". The Tuscaloosa News. Oct 10, 1945.

- "Anti-Russian Organization Rises In Japan; Red Liaison Officer Says That American Occupation Too Soft". Times Daily. Oct 9, 1945.

- "TOKYO COMMUNISTS, KOREANS SHOUT OPPOSITION TO HIROHITO". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Oct 10, 1945.

- "CHANGES IN JAPAN". Kalgoorie Miner. Oct 12, 1945.

- "Reds Stage Parade, Ask Hirohito Ouster". Lodi News-Sentinel. Oct 11, 1945.

- Japanese Press Translations produced by the General Headquarters of SCAP

- Mary Koehler slides, photographs documenting her experiences as secretary to the Chief of the Forestry Division, Natural Resources Section, General Headquarters, Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, 1945 - 1949. at the University of Maryland libraries

- Robert P. Schuster photographs and negatives, photographs from the experiences of medical equipment repair specialist for the Allied Forces in 1946. At the University of Maryland libraries.

.svg.png.webp)