Umm Al Nar culture

Umm Al Nar (Arabic: أُمّ الـنَّـار, romanized: Umm an-Nār or Umm al-Nar, lit. 'Mother of the Fire') is a Bronze Age culture that existed around 2600-2000 BCE in the area of modern-day United Arab Emirates and Northern Oman. The Arabic name has in the past frequently been transliterated as Umm an-Nar and also Umm al-Nar. The etymology derives from the island of the same name which lies adjacent to Abu Dhabi city and which provided early evidence and finds attributed to the period.[1][2]

Umm Al Nar

| |

|---|---|

Umm Al Nar | |

| Coordinates: 24°26′18″N 54°30′52″E | |

| Country | |

| Elevation | 5 m (16 ft) |

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of the United Arab Emirates |

|

|

|

Location

The key site is well protected, but its location between a refinery and a sensitive military area means public access is currently restricted. The UAE authorities are working to improve public access to the site, and plan to make this an Abu Dhabi cultural location.

Attributes

One element of the Umm Al Nar culture is circular tombs typically characterized by well fitted stones in the outer wall and multiple human remains within.[3] The tombs are frequently associated with towers, many of which were built around water sources.[4]

The Umm Al Nar culture covers around five or six centuries (2600-2000 BCE). The name is derived from Umm Al Nar, a small island located on the southeast of the much larger island Abu Dhabi. It is one of 200 islands that dominate the coast of Abu Dhabi.

Excavations

The first archaeological excavations in Abu Dhabi began at Umm Al Nar in 1959, twelve years before the foundation of the United Arab Emirates. Seven tombs from a total of fifty and three areas at the ruins of the ancient settlement were examined by the Danish Archaeological Expedition. During their first visit they identified a few exposed shaped stones fitted together at some of the stone mounds. The following year (February 1959) the first excavations started at one of the mounds on the plateau, now called Tomb I. Two more seasons (1960 and 1961) involved digging more tombs, while the last three seasons (1962/1963, 1964 and 1965) were allocated to examining the settlement.

The Danish excavations on Umm Al Nar halted in 1965 but were resumed in 1975 by an archaeological team from Iraq. During the Iraqi excavations which lasted one season, five tombs were excavated and a small section of the village was examined. Between 1970 and 1972 an Iraqi restoration team headed by Shah Al Siwani, former member of the Antiquities Director in Baghdad, restored and/or reconstructed the Danish excavated tombs.

At Al Sufouh Archaeological Site in Dubai, archaeological excavation between 1994 and 1995 revealed an Umm Al Nar type circular tomb dating between 2500 and 2000 B.C. An Umm Al Nar tomb is at the centre of the Mleiha Archaeological Centre in Sharjah.

Dilmun Burial Mounds in Bahrain also feature Umm Al Nar Culture remains.

At Tell Abraq, settlements associated with the start of the Umm Al Nar Culture began c. 2500 BCE.

Occupation phases

The Ubaid period (5,000-3,800 BCE) followed the neolithic Arabian bifacial era. Pottery vessels of the period already show contact with Mesopotamia.[3]

The Hafit period followed the Ubaid period. During the Hafit period (3200 - 2600 BCE) burial cairns with the appearance of a beehive appeared, consisting of a small chamber for one to two burials.

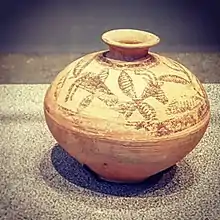

The distinctive circular tombs of the Umm Al Nar period (2,600-2,000 BCE) distinguish it from the preceding Hafit period, together with finds of distinctive black on red decorated pottery and jewellery made with gems such as carnelian, sourced from the Indus Valley.

A number of important Umm Al Nar sites in the UAE such as Hili, Badiyah, Tell Abraq and Kalba feature large, towers presumably defensive in purpose. At Tell Abraq, this fortification is 40 metres in diameter, but most are between 16 and 25 metres.[5] These fortifications typically are built around a well, presumably to protect important water resources.

During this period, the first Sumerian mentions of a land of Magan (Akkadian Makkan) are made, as well as references to 'the Lords of Magan'. Sumerian sources also point to 'Tilmun' (accepted today as modern Bahrain) and Meluhha (thought to refer to the Indus Valley).[5] Akkadian campaigns against Magan took place in the twenty-third century, again possibly explaining the need for fortifications, and both Manishtusu and Naram-Sin and Manishtusu, in particular, wrote of campaigning against '32 lords of Magan'.[5]

Magan was famed for its shipbuilding and its maritime capabilities. King Sargon of Agade (2,371-2,316 BCE) boasted that his ports were home to boats from Tilmun, Magan and Meluhha. His successor, Naram-Sin, not only conquered Magan, but honoured the Magan King Manium by naming the city of Manium-Ki in Mesopotamia after him. Trade between the Indus Valley and Sumer took place through Magan, although that trade appears to have been interrupted, as Ur-Nammu (2,113-2,096 BCE) laid claim to having 'brought back the ships of Magan'.[6]

Archaeological finds dating from this time show trade not only with the Indus Valley and Sumer, but also with Iran and Bactria.[7] They have also revealed what is thought to be the oldest case on record of poliomyelitis, with the distinctive signs of the disease found in the skeleton of a woman from Tell Abraq.[7]

Domestic manufactures in the late third millennium included soft-stone vessels, decorated with dotted circles. These, in the shapes of beakers, bowls and compartmentalised boxes, are distinctive.[8]

The trade with Mesopotamia collapsed in and around 2,000 BCE, with a series of disasters including the Aryan invasion of the Indus Valley,[9] the fall of the Mesopotamian city of Ur to Elam in 2,000 BC and the decline of the Indus Valley Harappan Culture in 1800 BC. The abandonment of the port of Umm Al Nar took place at around this time.[10]

There is some dispute as to the exact cause of the end of the trading era of the Umm Al Nar period and the inwardly focused domestication of the Wadi Suq period, but archaeologists are generally agreed that the domestication of the camel at around this time led to nomadism and something of a 'Dark Age' in the area. Modern consensus is that the transition from the Umm Al Nar to the Wadi Suq period was evolutionary and not revolutionary.[11][12]

After Umm Al Nar, the Wadi Suq culture followed (2,000-1,300 BCE), a period which saw more inland settlement, increasingly sophisticated metallurgy and the domestication of the camel.

The poorly represented last phase of the Bronze Age (1,600-1,300 BCE) has only been vaguely identified in a small number of settlements. This last phase of the Bronze Age was followed by a boom when the underground irrigation system (the qanāt (Persian: قَنات), here called falaj (Arabic: فَـلَـج)) was introduced during the Iron Age (1300-300 BCE) by local communities.[13]

References

- UAE History: 20,000 - 2,000 years ago - UAEinteract Archived 2013-06-13 at the Wayback Machine

- "UNESCO - Tentative Lists". Settlement and Cemetery of Umm an-Nar Island. UNESCO. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- "Introduction to the Archaeology of Ras Al Khaimah", rakheritage.rak.ae

- The Persian Gulf in history. Potter, Lawrence G. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. 2009. pp. 27–38. ISBN 9780230618459. OCLC 319175648.CS1 maint: others (link)

- United Arab Emirates : a new perspective. Abed, Ibrahim., Hellyer, Peter. London: Trident Press. 2001. p. 40. ISBN 1900724472. OCLC 47140175.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Donald., Hawley (1970). The Trucial States. London: Allen & Unwin. p. 27. ISBN 0049530054. OCLC 152680.

- United Arab Emirates : a new perspective. Abed, Ibrahim., Hellyer, Peter. London: Trident Press. 2001. p. 43. ISBN 1900724472. OCLC 47140175.CS1 maint: others (link)

- United Arab Emirates : a new perspective. Abed, Ibrahim., Hellyer, Peter. London: Trident Press. 2001. p. 46. ISBN 1900724472. OCLC 47140175.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Donald., Hawley (1970). The Trucial States. London: Allen & Unwin. p. 29. ISBN 0049530054. OCLC 152680.

- 1963-, Hawker, Ronald William (2008). Traditional architecture of the Arabian Gulf : building on desert tides. Southampton, UK: WIT. ISBN 9781845641351. OCLC 191244229.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- United Arab Emirates : a new perspective. Abed, Ibrahim., Hellyer, Peter. London: Trident Press. 2001. p. 44. ISBN 1900724472. OCLC 47140175.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Gregoricka, L. A. (2016-03-01). "Human Response to Climate Change during the Umm an-Nar/Wadi Suq Transition in the United Arab Emirates". International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. 26 (2): 211–220. doi:10.1002/oa.2409. ISSN 1099-1212.

- The Island of Umm-an-Nar Volume 1: Third Millennium Graves (Jutland Archaeological Society Publications) (v. 1) [Hardcover] Karen Frifelt (Author), Ella Hoch (Contributor), Manfred Kunter (Contributor), David S. Reese (Contributor)]; Island of Umm-an-Nar Volume 2: The Third Millennium Settlement (Jutland Archaeological Society Publications) December 1, 1995]

Bibliography

- P. Yule–G. Weisgerber, The Tower Tombs at Shir, Eastern Ḥajar, Sultanate of Oman, in: Beiträge zur allgemeinen und vergleichenden Archäologie (BAVA) 18, 1998, 183–241, ISBN 3-8053-2518-5.

- Karen Frifelt, The Island of Umm-an-Nar. Jutland Archaeologcia Society Publications, Aarhus 1995

- Walid Yasin Al Tikriti: Archaeology of Umm an-Nar Island (1959–2009). Abu Dhabi Culture & Heritage, Department of Historic Environment, Abu Dhabi 2011

- About Umm an-Nar culture, at academia.edu website:

- Charlotte Marie Cable, Christopher P. Thornton: Monumentality and the Third-millennium “Towers” of the Oman Peninsula. online

- Daniel T. Potts: The Hafit – Umm an-Nar transition: Evidence from Falaj al-Qaba'il and Jabal al-Emalah. In. J. Giraud, G. Gernez, V. de Castéja (Hrsg.): Aux marges de l'archéologie: Hommages à Serge Cleuziou. Paris 2012: Travaux de la Maison René-Ginouves 16, S. 371–377. online