Unemployment in Spain

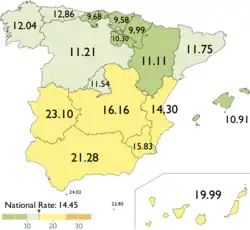

Unemployment rates in Spain vary across different regions of the country, but they tend to be higher when compared to other Western European countries.

Unemployment rates in Spain rose sharply during the late 2000s and early 2010s. Unemployment was at 8% between 2006 and 2007. Starting in 2008, the Spanish economic crisis caused the rate to rise past 20% in 2010 and 25% in 2012.

Introduction

Spain has one of the highest unemployment rates compared to other OECD countries.[1] The Q4 2017 unemployment rate is 16.6% of labor force.[2] There has been an upward trend since the 1990s, and this trend has historic roots.[3] Unemployment began rising in Francoist Spain during the 1970s.[4] During the Francoist Spain, trade union activism was prohibited and social security benefits of the modern welfare state were lacking. In 1972, 2.7 million jobs in agriculture were replaced by 1.1 million jobs in the public sector, further increasing unemployment.[5] Although unemployment is a problem in other OECD countries such as Italy and Turkey, data shows that the extent of increase and the persistence is much larger in Spain.[6] Moreover, Catholic countries such as Spain often have very low female workers participation rate,[7] resulting in a worsening employment rate as a new generation of women beginning to pursue work. Net employment creation has been negative since 1973, meaning new jobs aren’t being created to sustain development.[8]

Causes

Spain suffers a high level of structural unemployment. Since the economic and financial crisis of the 1980s, unemployment has never dipped below 8%. Spain has the fourth highest unemployment rate in the OECD, after Portugal, Italy, and Greece. One leading cause is an economy based mostly on tourism and building sectors, as well as lack of industry. The most industrialized region is Basque Country (where industry is around 20–25% of its GDP); its unemployment rate is 2.5 times lower than those of Andalusia and the Canary Islands (where industry is only 5–10% of their respective GDP). In the last thirty years, the Spanish unemployment rate has hovered around double the average of developed countries, in times of growth and in times of crisis. From the start of the crisis of the 1990s, unemployment fell from 3.6 million to two million, however that figure stagnated throughout the stable times to the present crisis.

Consequences

Unemployment benefits are high enough in Spain to sustain basic expenses, though special consideration is only given to those in the first year of being unemployed.[9] Those that are unemployed are at the risk of losing their home. According to research data by Amnesty International,[10] thousands of people are being forcibly evicted without alternative accommodation by the state. Among these include approximately 26,800 rental evictions and 17,000 mortgage evictions. As unemployment is rising higher in Spain, there is limited public spending on housing that would grant necessary shelter. Women traditionally are not trained for the workforce, therefore single mothers and survivors of gender violence are particularly affected. This is, however, changing with a rise of women enrolling in higher education.[11] In July 2018, the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights upheld a complaint against Spain for not having means of alternative housing for evicted families.[12] Due to high unemployment levels, employed workers are afraid of losing their jobs and are more reluctant to refute existing working conditions. There are reforms being undertaken by the government in Spain to address this, including reduction of temporary work contracts.[13]

Socio-economic consequences

Unemployment reduces household income which in turn diminishes domestic consumption and quality of life. The mental health of the unemployed and their families deteriorates. The emancipation period is extended and consequently the birth rate decreases as it is difficult to start a family with minimal economic guarantees. Social exclusion is triggered, evictions increase, and families start to default on bills for basic utilities such as water, electricity and gas, leading to energy poverty.

Unemployment and inclusion of people with disabilities

There are efforts in Spain to integrate people with disabilities into the workforce.[14] These efforts include a plan to normalize disability in the work environment with training and professional development implementation.[15] According to the survey of the Spanish National Statistics Institute, 8.5% of the Spanish population is disabled.[16] Disability has a correlation with seniority, as more than 34.7% disabled individuals are over 65.[17] According to data, there are more disabled women than disabled men.[18] In general, disabled people have more difficulties carrying out basic activities and due to these economic hardships. Many people argue that government and economic aid is imperative.[19] Unemployment is one of the largest issues the Spanish disabled community faces. More than 87.1% of disabled people that are able to work don't have a job, and often have difficulty finding one due to labor market barriers.[20] Some factors addressing unemployment among the disabled include insufficient education, lack of information, negative attitude from some employers and HR representatives, and insufficient means of transportation or training.[21] While there are measures being taken to promote employment among the disabled, there is still growth in the number of disabled seeking a job. One measure is the Law for Disabled Peoples' Social Integration, which requires companies with over 50 employees to be made up of at least 2 percent disabled workers.[22]

Unemployment rate

Unemployment rates are obtained through a procedure known as the Economically Active Population Survey. It is taken every three months. The survey divides the population of 16 years or older into four groups:

- Occupied people: Those who have carried out paid work, as well as those that have jobs but are absent because of illness, strikes or holiday.

- Unemployed: are the people that are not occupied, but that they have sought work actively or are waiting to return to work. More exactly, 1) a person is unemployed if he/she is not working and has made specific efforts to find employ during the last four weeks; 2) has been suspended from employment and is waiting to be called new or 3) is waiting to occupy a job the following month.

- Inactive: This category includes the percentage of adult population that is studying, does household chores, is retired, is too sick to work or is simply not looking for work.

- Active Population: includes persons who are both employed and the unemployed.

The unemployment rate is calculated as the number of unemployed workers divided into the active population, and is expressed as a percentage. In other words, it is not a proportion between the total of the unemployed people and the total population, but economically active people.

Women in the economy

In Francoist Spain, women found themselves living under a conservative gender ideology, where they were viewed as being consumers and producers of the market economy.[23] Under the authoritarian system of the Spanish State, nationalistic pride situated women in a role meant to serve best the state and the nation, which consisted in the domestic work of nurturing and caring for children. If these roles steered outside the household, they were best funneled through the work sector of teaching and nursing.[24] The culture of Spain, with its fluctuation of political leadership, visibly demonstrates the fluctuation of sovereignty for women’s rights in the country. Between 1931-1936, the Second Republic generated legislation for women granting them new rights of which they were deprived of before. During this period of time, European countries were experiencing a movement towards the equalization of the sexes, which was reflected in the constitution of the New Republic. The constitution extensively accorded women legitimate status under laws on civil marriage and divorce.[25] With the Spanish Coup of July 1936, legal measures that progressed women into the social and economic sector of equal access into the labor market became restricted once again, under the desire of restricting women to the confines of the private sphere of domestic work.[26]

The period of transition to democracy carved the way for the reemergence of women in social and economic participation. A revival of sorts for women took initiative in the late 1970s, with the re-emergence of legality in the social atmosphere of Spain; in particular to the restoration of free and equal access to work and right to hire.[27] With women being able to return to the workplace, a significant shift took place in relation to the family life. Domestic life for women was shifting away from normality and into career pursuits. During La Transicion, participation rates in the labor force steadily grew due to structural shifts in education, and birth rates decreased which caused an increased rate in 1975 of 30.20, followed by 34.71 in 1982, and 41.20 in 1986.[28] In addition to the progression of women in the workforce, the elimination of Franco’s “Fuero del Trabajo” in 1938, which enforced the replacement of women workers with men, serves as a reminder of how far woman have come in terms of women’s active role in the economic development of Spain.[29] Although progress has been made, it is still from being considered a pure gender equal state. A wage gap exists in Spain, where in 2005, women residing in Spain earned 72 percent less than men did.[30]

Due to legislation better serving opportunities for women, this once marginalized group has seen progress within the country of Spain, but not to the extent of full equality. On March 8, 2018, Spain underwent a 24-hour strike on International Women’s Day, where women were backed by unions in support of gender equality between women and men. Roughly 5.3 million people went on strike. This was representative of both male and female participation, because Spain’s union laws prohibit strikes if they only apply to one of the sexes. The turnout represented 11 percent of the population and 23 percent of the labor force.[31] Justification for the strike appeared to be approved by 82 percent of people. As argued by the participants of the strike (although previous legislation has to an extent helped women), Spain’s public sector still finds that men make an average of 13 percent more than women and 19 percent more than women in the private sector. In 2016, women in the European Union earning gross hourly earnings 16.2 percent below those of their male counterparts on average.[32] According to reports by Eurostat, the “explained” gender gap in Spain is roughly 4 percent in account of variation in characteristics for both women and men in regards to the occupational and sectional segregation in the labor markets.[33]

See also

- Unemployment

- Financial crisis of 2007–08

- Spanish property bubble

- Eviction

References

This article was adapted from the equivalent Spanish-language Wikipedia article on April 20, 2013.

- "Unemployment Rate". OECD Data.

- "Unemployment Rate". OECD Data.

- Dolado & Jimeno (July 1997). "The causes of Spanish unemployment: A structural VAR approach". Economic European Review. 41 (7): 1282. doi:10.1016/S0014-2921(97)00058-5. hdl:10016/3274.

- Dolado & Jimeno (July 1997). "The causes of Spanish unemployment: A structural VAR approach". Economic European Review. 41 (7): 1282. doi:10.1016/S0014-2921(97)00058-5. hdl:10016/3274.

- Dolado & Jimeno (July 1997). "The causes of Spanish unemployment: A structural VAR approach". Economic European Review. 41 (7): 1290. doi:10.1016/S0014-2921(97)00058-5. hdl:10016/3274.

- "Unemployment Rate". OECD Data.

- Dolado & Jimeno (July 1997). "The causes of Spanish unemployment: A structural VAR approach". Economic European Review. 41 (7): 1284. doi:10.1016/S0014-2921(97)00058-5. hdl:10016/3274.

- Dolado & Jimeno (July 1997). "The causes of Spanish unemployment: A structural VAR approach". Economic European Review. 41 (7): 1282. doi:10.1016/S0014-2921(97)00058-5. hdl:10016/3274.

- "Unemployment procedures and benefits in Spain". EURAXESS Spain. 28 February 2017.

- "Spain 2017/2018". Amnesty International. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- "Spain - SOCIAL VALUES AND ATTITUDES". countrystudies.us.

- "Spain 2017/2018". Amnesty International. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- "Spain: Agreement to reduce temporary employment in public administration | Eurofound". www.eurofound.europa.eu. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- Perez-Conesa & Romeo (Sep 20, 2017). "Taylor & Francis Online". The International Journal of Human Resource Management.

- Perez-Conesa & Romeo (Sep 20, 2017). "Taylor & Francis Online". The International Journal of Human Resource Management.

- "A review of the situation of disabled people and the welfare system in Spain" (PDF). TRAVORS. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- "A review of the situation of disabled people and the welfare system in Spain" (PDF). TRAVORS. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- "A review of the situation of disabled people and the welfare system in Spain" (PDF). TRAVORS. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- "A review of the situation of disabled people and the welfare system in Spain" (PDF). TRAVORS. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- "A review of the situation of disabled people and the welfare system in Spain" (PDF). TRAVORS. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- Perez-Conesa & Romeo (Sep 20, 2017). "Taylor & Francis Online". The International Journal of Human Resource Management.

- "A review of the situation of disabled people and the welfare system in Spain" (PDF). TRAVORS. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- Lannon, Frances (10 June 2003). "True Catholic Womanhood: Gender Ideology in Franco's Spain (review)". The Catholic Historical Review. 89 (2): 320–321. doi:10.1353/cat.2003.0124.

- Lannon, Frances (10 June 2003). "True Catholic Womanhood: Gender Ideology in Franco's Spain (review)". The Catholic Historical Review. 89 (2): 320–321. doi:10.1353/cat.2003.0124.

- A. Sponsler, Lucy (1982). "The Status of Married Women Under the Legal System of Spain". 5. 42 (Louisiana Law Review): 1600–1628. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Pardell, Agnès. "SPAIN : WOMEN AND POLITICS in Spain". www.helsinki.fi. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- Pardell, Agnès. "SPAIN : WOMEN AND POLITICS in Spain". www.helsinki.fi. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- Yerevan, Armenia (June 10, 2014). "Women, Leadership and Society" (PDF). Women, Transition and Social Changes. The Case of Spain, 1976-1986: 1–11. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- A. García Fernández del Viso, José. "Conquistas sociales del Fuero del Trabajo". Fundacion Nacional Francisco Franco. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- Philips, Kristi (2010). "Women's labor force participation in Spain: An analysis from dictatorship to democracy". UNI Scholar Works (Honors Program Theses. 86): 2–38. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- Sweeney, Sean. "Spanish unions strike, women in multiple cities hold protests for International Women's Day | The Knife Media". The Knife Media. The Knife Media. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- Povoledo, Elisabetta; Minder, Raphael; Joseph, Yonette (8 March 2018). "International Women's Day 2018: Beyond #MeToo, With Pride, Protests and Pressure". The New York Times. The New York Times. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- "Gender pay gap statistics - Statistics Explained". ec.europa.eu. Eurostat. Retrieved 3 May 2018.