Unix filesystem

In Unix and operating systems inspired by it, the file system is considered a central component of the operating system.[1] It was also one of the first parts of the system to be designed and implemented by Ken Thompson in the first experimental version of Unix, dated 1969.[2]

As in other operating systems, the filesystem provides information storage and retrieval, and one of several forms of interprocess communication, in that the many small programs that traditionally form a Unix system can store information in files so that other programs can read them, although pipes complemented it in this role starting with the Third Edition. Also, the filesystem provides access to other resources through so-called device files that are entry points to terminals, printers, and mice.

The rest of this article uses Unix as a generic name to refer to both the original Unix operating system and its many workalikes.

Principles

The filesystem appears as one rooted tree of directories.[1] Instead of addressing separate volumes such as disk partitions, removable media, and network shares as separate trees (as done in DOS and Windows: each drive has a drive letter that denotes the root of its file system tree), such volumes can be mounted on a directory, causing the volume's file system tree to appear as that directory in the larger tree.[1] The root of the entire tree is denoted /.

In the original Bell Labs Unix, a two-disk setup was customary, where the first disk contained startup programs, while the second contained users' files and programs. This second disk was mounted at the empty directory named usr on the first disk, causing the two disks to appear as one filesystem, with the second disk’s contents viewable at /usr.

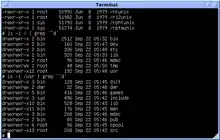

Unix directories do not contain files. Instead, they contain the names of files paired with references to so-called inodes, which in turn contain both the file and its metadata (owner, permissions, time of last access, etc., but no name). Multiple names in the file system may refer to the same file, a feature termed a hard link.[1] The mathematical traits of hard links make the file system a limited type of directed acyclic graph, although the directories still form a tree, as they typically may not be hard-linked. (As originally envisioned in 1969, the Unix file system would in fact be used as a general graph with hard links to directories providing navigation, instead of path names.[2])

File types

The original Unix file system supported three types of files: ordinary files, directories, and "special files", also termed device files.[1] The Berkeley Software Distribution (BSD) and System V each added a file type to be used for interprocess communication: BSD added sockets,[3] while System V added FIFO files.

BSD also added symbolic links (often termed "symlinks") to the range of file types, which are files that refer to other files, and complement hard links.[3] Symlinks were modeled after a similar feature in Multics,[4] and differ from hard links in that they may span filesystems and that their existence is independent of the target object. Other Unix systems may support additional types of files.[5]

Conventional directory layout

Certain conventions exist for locating some kinds of files, such as programs, system configuration files, and users' home directories. These were first documented in the hier(7) man page since Version 7 Unix;[6] subsequent versions, derivatives and clones typically have a similar man page.[7][8][9][10][11][12]

The details of the directory layout have varied over time. Although the file system layout is not part of the Single UNIX Specification, several attempts exist to standardize (parts of) it, such as the System V Application Binary Interface, the Intel Binary Compatibility Standard, the Common Operating System Environment, and Linux Foundation's Filesystem Hierarchy Standard (FHS).[13]

Here is a generalized overview of common locations of files on a Unix operating system:

| Directory or file | Description |

|---|---|

/ |

The slash / character alone denotes the root of the filesystem tree. |

|

Stands for binaries and contains certain fundamental utilities, such as ls or cp, that are needed to mount /usr, when that is a separate filesystem, or to run in one-user (administrative) mode when /usr cannot be mounted. In System V.4, this is a symlink to /usr/bin. Otherwise, it needs to be on the root filesystem itself. |

| Contains all the files needed for successful booting process. In Research Unix, this was one file rather than a directory.[14] Nowadays usually on the root filesystem itself, unless the system, bootloader etc. require otherwise. | |

| Stands for devices. Contains file representations of peripheral devices and pseudo-devices. See also: Linux Assigned Names and Numbers Authority. Needs to be on the root filesystem itself. | |

|

Contains system-wide configuration files and system databases; the name stands for et cetera.[14] Originally also contained "dangerous maintenance utilities" such as init,[6] but these have typically been moved to /sbin or elsewhere. Needs to be on the root filesystem itself. |

|

Contains user home directories on Linux and some other systems. In the original version of Unix, home directories were in /usr instead.[15] Some systems use or have used different locations still: macOS has home directories in /Users, older versions of BSD put them in /u, FreeBSD has /usr/home. |

|

Originally essential libraries: C libraries, but not Fortran ones.[14] On modern systems, it contains the shared libraries needed by programs in /bin, and possibly loadable kernel module or device drivers. Linux distributions may have variants /lib32 and /lib64 for multi-architecture support. |

|

Default mount point for removable devices, such as USB sticks, media players, etc. By common sense, the directory itself, whose subdirectories are mountpoints, is on the root partition itself. |

|

Stands for mount. Empty directory commonly used by system administrators as a temporary mount point. By common sense, the directory itself, whose subdirectories are mountpoints, is on the root partition itself. |

|

Contains locally installed software. Originated in System V, which has a package manager that installs software to this directory (one subdirectory per package).[16] |

|

procfs virtual filesystem showing information about processes as files. |

|

The home directory for the superuser root - that is, the system administrator. This account's home directory is usually on the initial filesystem, and hence not in /home (which may be a mount point for another filesystem) in case specific maintenance needs to be performed, during which other filesystems are not available. Such a case could occur, for example, if a hard disk drive suffers physical failures and cannot be properly mounted. By convention, this directory is on the root partition itself; in any case, it is not a link to /home/root or any such thing. |

|

Stands for "system (or superuser) binaries" and contains fundamental utilities, such as init, usually needed to start, maintain and recover the system. Needs to be on the root partition itself. |

|

Server data (data for services provided by system). |

|

In some Linux distributions, contains a sysfs virtual filesystem, containing information related to hardware and the operating system. On BSD systems, commonly a symlink to the kernel sources in /usr/src/sys. |

|

A place for temporary files not expected to survive a reboot. Many systems clear this directory upon startup or use tmpfs to implement it. |

|

The Unix kernel in Research Unix and System V.[14] With the addition of virtual memory support to 3BSD, this got renamed /vmunix. |

|

The "user file system": originally the directory holding user home directories,[15] but already by the Third Edition of Research Unix, ca. 1973, reused to split the operating system's programs over two disks (one of them a 256K fixed-head drive) so that basic commands would either appear in /bin or /usr/bin.[17] It now holds executables, libraries, and shared resources that are not system critical, like the X Window System, KDE, Perl, etc. In older Unix systems, user home directories might still appear in /usr alongside directories containing programs, although by 1984 this depended on local customs.[14] |

|

Stores the development headers used throughout the system. Header files are mostly used by the #include directive in C language, which historically is how the name of this directory was chosen. |

|

Stores the needed libraries and data files for programs stored within /usr or elsewhere. |

|

Holds programs meant to be executed by other programs rather than by users directly. E.g., the Sendmail executable may be found in this directory.[18] Not present in the FHS until 2011;[19] Linux distributions have traditionally moved the contents of this directory into /usr/lib, where they also resided in 4.3BSD. |

|

Resembles /usr in structure, but its subdirectories are used for additions not part of the operating system distribution, such as custom programs or files from a BSD Ports collection. Usually has subdirectories such as /usr/local/lib or /usr/local/bin. |

|

Architecture-independent program data. On Linux and modern BSD derivatives, this directory has subdirectories such as man for manpages, that used to appear directly under /usr in older versions. |

|

Stands for variable. A place for files that might change frequently - especially in size, for example e-mail sent to users on the system, or process-ID lock files. |

|

Contains system log files. |

|

The place where all incoming mail is stored. Users (other than root) can access their own mail only. Often, this directory is a symbolic link to /var/spool/mail. |

|

Spool directory. Contains print jobs, mail spools and other queued tasks. |

|

The place where the uncompiled source code of some programs is. |

|

The /var/tmp directory is a place for temporary files which should be preserved between system reboots. |

See also

References

- This article incorporates material from the Citizendium article "Unix filesystem", which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License but not under the GFDL.

- Ritchie, D.M.; Thompson, K. (July 1978). "The UNIX Time-Sharing System". Bell System Tech. J. 57 (6): 1905–1929. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.112.595. doi:10.1002/j.1538-7305.1978.tb02136.x.

- Ritchie, Dennis M. (1979). The Evolution of the Unix Time-sharing System. Language Design and Programming Methodology Conf.

- Leffler, Samuel J.; McKusick, Marshall Kirk; Karels, Michael J.; Quarterman, John S. (October 1989). The Design and Implementation of the 4.3BSD UNIX Operating System. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-201-06196-3.

- McKusick, Marshall Kirk; et al. "A Fast Filesystem for Unix" (PDF). Freebsd.org. CSRG, UC Berkeley. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- – Linux Programmer's Manual – System Calls

- – Version 7 Unix Programmer's Manual

- – FreeBSD Miscellaneous Information Manual

- – OpenBSD Miscellaneous Information Manual

- "hier(7) man page for 2.9.1 BSD".

- "hier(7) man page for ULTRIX 4.2".

- "hier(7) man page for SunOS 4.1.3".

- – Linux Programmer's Manual – Overview, Conventions and Miscellanea

- George Kraft IV (1 November 2000). "Where to Install My Products on Linux?". Linux Journal. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- Kernighan, Brian W.; Pike, Rob (1984). The UNIX Programming Environment. Prentice-Hall. pp. 63–65. Bibcode:1984upe..book.....K.

- Ritchie, Dennis. "Unix Notes from 1972". Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- System V Application Binary Interface Edition 4.1 (1997-03-18)

- M. D. McIlroy (1987). A Research Unix reader: annotated excerpts from the Programmer's Manual, 1971–1986. CSTR 139, Bell Labs.

- "Chapter 7. sendmail". UNICOS/mp Networking Facilities Administration. Cray. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- "fhs-spec revision 44".