Urethral stricture

A urethral stricture is a narrowing of the urethra caused by injury, instrumentation, infection, and certain non-infectious forms of urethritis.[1]

| Urethral stricture | |

|---|---|

| |

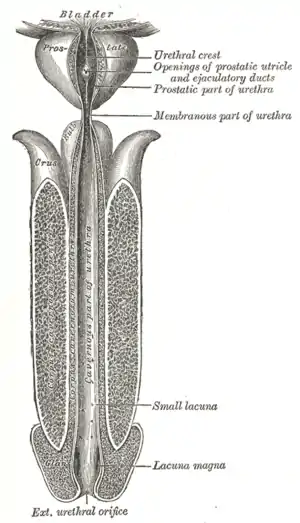

| Urethra is tube at center. | |

| Specialty | Urology |

Signs and symptoms

The hallmark sign of urethral stricture is a weak urinary stream. Other symptoms include:

- Splaying of the urinary stream

- Urinary frequency

- Urinary urgency

- Straining to urinate

- Pain during urination

- Urinary tract infection

- Prostatitis

- Inability to completely empty the bladder.

Some people with severe urethral strictures are completely unable to urinate. This is referred to as acute urinary retention, and is a medical emergency. Hydronephrosis and kidney failure may also occur.

Complications

- Urinary retention

- Prostatitis

- Bladder dysfunction

- Urethral diverticulum

- Periurethral abscess

- Fournier's gangrene

- Urethral fistula

- Bilateral hydronephrosis

- Urinary infections

- Urinary calculus

Causes

Urethral strictures most commonly result from injury, urethral instrumentation, infection, non-infectious inflammatory conditions of the urethra, and after prior hypospadias surgery. Less common causes include congenital urethral strictures and those resulting from malignancy.

Urethral strictures after blunt trauma can generally be divided into two sub-types;

- Pelvic fracture-associated urethral disruption occurs in as many as 15% of severe pelvic fractures.[2] These injuries are typically managed with suprapubic tube placement and delayed urethroplasty 3 months later. Early endoscopic realignment may be used in select cases instead of a suprapubic tube, but these patients should be monitored closely as vast majority of them will require urethroplasty.[3]

- Blunt trauma to the perineum compresses the bulbar urethra against the pubic symphysis, causing a "crush" injury. These patients are typically treated with suprapubic tube and delayed urethroplasty.

Other specific causes of urethral stricture include:

- Instrumentation (e.g., after transurethral resection of prostate, transurethral resection of bladder tumor, or endoscopic kidney surgery)

- Infection (typically with Gonorrhea)

- Lichen sclerosus[4]

- Surgery to address hypospadias can result in a delayed urethral stricture, even decades after the original surgery.

Diagnosis

Treatment

Dilation and other endoscopic approaches

Urethral dilation and other endoscopic approaches such as direct vision internal urethrotomy (DVIU), laser urethrotomy, and self intermittent dilation are the most commonly used treatments for urethral stricture. However, these approaches are associated with low success rates[5] and may worsen the stricture, making future attempts to surgically repair the urethra more difficult.[6]

A Cochrane review found that performing intermittent self-dilatation may confer a reduced risk of recurrent urethral stricture after endoscopic treatment, but the evidence is weak.[7]

Cell therapy approach through endoscopy

Buccal mucosal tissue harvested under local anesthesia after culturing in the lab when applied through endoscopy after urethrotomy in a pilot study has yielded encouraging results. This method named as BEES-HAUS procedure needs to be validated through a larger multicentric study before becoming a routine application.[8]

Urethroplasty

Urethroplasty refers to any open reconstruction of the urethra. Success rates range from 85% to 95% and depend on a variety of clinical factors, such as stricture as the cause, length, location, and caliber.[9][10][11][12] Urethroplasty can be performed safely on men of all ages.[13]

In the posterior urethra, anastomotic urethroplasty (with or without preservation of bulbar arteries) is typically performed after removing scar tissue.

In the bulbar urethra,[9][10][11] the most common types of urethroplasty are anastomotic (with or without preservation of corpus spongiosum and bulbar arteries) and substitution with buccal mucosa graft, full-thickness skin graft, or split thickness skin graft. These are nearly always done in a single setting (or stage).

In the penile urethra, anastomotic urethroplasties are rare because they can lead to chordee (penile curvature due to a shortened urethra). Instead, most penile urethroplasties are substitution procedures utilizing buccal mucosa graft, full-thickness skin graft, or split thickness skin graft. These can be done in one or more setting, depending on stricture location, severity, cause and patient or surgeon preference.

The first reported cases using umbilical vein as urethral graft in urethral stricture yielded good results 85% , Al-Naieb in 1985 . the first 10 cases were reported in his PhD thesis submitted to Johannes Gutenberg university in Mainz Germany. after this successful results, 25 cases operated and published in Jordanian medical Journal in the nineties . with excellent results mainly posterior urethra. published as Editorial in 2019:.EC Gynaecology 8.1 (21019): 01-12.

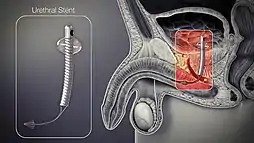

Urethral stent

A permanent urethral stent[14] was approved for use in men with bulbar urethral strictures in 1996, but was recently removed from the market.

A temporary thermoexpandable urethral stent (Memotherm) is available in Europe, but is not currently approved for use in the United States.

Emergency treatment

When in acute urinary retention, treatment of the urethral stricture or diversion is an emergency. Options include:

- Urethral dilatation and catheter placement. This can be performed in the Emergency Department, a practitioner's office or an operating room. The advantage of this approach is that the urethra may remain patent for a period of time after the dilation, though long-term success rates are low.

- Insertion of a suprapubic catheter with catheter drainage system. This procedure is performed in an Operating Room, Emergency Department or practitioner's office. The advantage of this approach is that it does not disrupt the scar and interfere with future definitive surgery.

Ongoing care

Following urethroplasty, patients should be monitored for a minimum of 1 year, since the vast majority of recurrences occur within 1 year.

Because of the high rate of recurrence following dilation and other endoscopic approaches, the provider must maintain a high index of suspicion for recurrence when the patient presents with obstructive voiding symptoms or urinary tract infection.

Research

The use of bioengineered urethral tissue is promising, but still in the early stages. The Wake Forest Institute of Regenerative Medicine has pioneered the first bioengineered human urethra, and in 2006 implanted urethral tissue grown on bioabsorbable scaffolding (approximating the size and shape of the affected areas) in five young (human) males who suffered from congenital defects, physical trauma, or an unspecified disorder necessitating urethral reconstruction. As of March, 2011, all five recipients report the transplants have functioned well.[15]

References

- "Urethral stricture: What causes it? - MayoClinic.com". MayoClinic.com. Archived from the original on November 26, 2007. Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- Figler, B. D.; Hoffler, C. E.; Reisman, W.; Carney, K. J.; Moore, T.; Feliciano, D.; Master, V. (2012). "Multi-disciplinary update on pelvic fracture associated bladder and urethral injuries". 43 (81): 242–249. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "American Urological Association - Urotrauma". www.auanet.org. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- Palminteri, E.; Brandes, S. B.; Djordjevic, M. (2012). "Urethral reconstruction in lichen sclerosus". Curr Opin Urol. 22 (6): 478–483. doi:10.1097/MOU.0b013e328358191c.

- Santucci R and Eisenberg L: Urethrotomy has a much lower success rate than previously reported. J Urol 2010; 183: 1859.

- Hudak SJ, Atkinson TH, Morey AF. Repeat transurethral manipulation of bulbar urethral strictures is associated with increased stricture complexity and prolonged disease duration. J Urol. 2012 May;187(5):1691-5

- Jackson, MJ; Veeratterapillay, R; Harding, CK; Dorkin, TJ (19 December 2014). "Intermittent self-dilatation for urethral stricture disease in males". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12: CD010258. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010258.pub2. PMID 25523166.

- Vaddi, Suryaprakash; Vijayabaskar, Reddy; Abraham, Samuel JK (22 November 2018). "Buccal epithelium Expanded and Encapsulated in Scaffold‐Hybrid Approach to Urethral Stricture (BEES‐HAUS) procedure: A novel cell therapy‐based pilot study". International Journal of Urology. 26 (2): 253–257. doi:10.1111/iju.13852. PMID 30468021.

- Santucci RA, Mario LA, McAninch JW. Anastomotic urethroplasty for bulbar urethral stricture: analysis of 168 patients. J Urol. 2002 Apr;167(4):1715-9.

- Figler BD, Malaeb BS, Dy GW, Voelzke BB, Wessells H. Impact of graft position on failure of single-stage bulbar urethroplasties with buccal mucosa graft. Urology. 2013 Nov;82(5):1166-70.

- Barbagli G1, Sansalone S, Romano G, Lazzeri M. Bulbar urethroplasty: transecting vs. nontransecting techniques. Curr Opin Urol. 2012 Nov;22(6):474-7.

- Bello JO. Impact of preoperative patient characteristics on posturethroplasty recurrence: the significance of stricture length and prior treatments. Niger J Surg. 2016; 22(2):86-89

- Santucci RA, McAninch JW, Mario LA et al. (July 2004). "Urethroplasty in patients older than 65 years: indications, results, outcomes and suggested treatment modifications". J Urol. 172 (1): 201–3.

- "Urolume Endoprosthesis". americanmedicalsystems.com. Archived from the original on 13 March 2006. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- Alice Park (8 March 2011). "Scientists Grow New Body Parts in the Lab". Time.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |