Vendel Period

In Swedish prehistory, the Vendel Period (c. 540–790) comes between the Migration Period and the Viking Age. The name is taken from the rich boat inhumation cemetery at Vendel parish church, Uppland. This is a period with very little precious metal and few runic inscriptions, sandwiched between periods with abundant precious metal and inscriptions. Instead, the Vendel Period is extremely rich in animal art on copper-alloy objects. It is also known for guldgubbar, tiny embossed gold foil images, and ostentatious helmets with embossed decoration such as the one exported and found at Sutton Hoo in England.[1]

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Sweden |

|

| Timeline |

|

|

During the period, the elder futhark was abandoned in favor of the younger futhark, virtually simultanously over the whole of Scandinavia. There are some Rune stones from the period, most notably those at Rök and Sparlösa, both from ca 800. Other written sources about the period are few and hard to interpretet: a few Icelandic sagas, the tale of Beowulf, and some souther European writers. Earlier Swedish historians tried to make use of these to create a coherent history, but this effort has largely been abandoned, and the period is now mostly studied by archaeologists.[2]

Swedish expeditions began to explore the waterways of what was to become Russia, Ukraine, Belarus at this time.

Background

The migrations and upheaval in Central Europe had lessened somewhat, and two power regions had appeared in Europe: the Merovingian kingdom and the Slavic princedoms in Eastern Europe and the Balkans. A third power, the Catholic Church, had begun to expand its influence.

In Uppland, in what today is the east-central part of Sweden, Old Uppsala was probably the centre of religious and political life. It had both a well-known sacred grove and great Royal Mounds. There were lively contacts with Central Europe, and the Scandinavians continued to export iron, fur, and slaves; in return they acquired art and innovations, such as the stirrup.

Burial customs

Several areas with rich burial gifts have been found, including well-preserved boat inhumation graves at Vendel and Valsgärde, and tumuli at Gamla Uppsala. These were used for several generations.

Some of the riches were probably acquired through the control of mining districts and the production of iron. The rulers had troops of mounted elite warriors with costly armour. Graves of mounted warriors have been found with stirrups and saddle ornaments of birds of prey in gilded bronze with encrusted garnets.

Rich grave goods indicate a royal or high status burial. For example chess pieces made by ivory by Roman design the western grave and buttons made of gold and three Middle Eastern cameos have also been found and Frankish clothes made of gold thread.[3]

Games were popular, as is shown in finds of tafl games, including pawns and dice.

The Sutton Hoo helmet very similar to helmets in Gamla Uppsala, Vendel and Valsgärde shows that the Anglo-Saxon elite had extensive contacts with Swedish elite. [4]

Written sources

Mounted elite warriors are mentioned in the work of the 6th century Goth scholar Jordanes, who wrote that the Swedes had the best horses beside the Thuringians. They also echo much later in the sagas, where king Adils is always described as fighting on horseback (both against Áli and Hrólf Kraki). Snorri Sturluson wrote that Adils had the best horses of his days. The epic of Beowulf also describes legendary tales about the Swedish Vendel times, including great wars called the Swedish-Geatish wars between the Swedish house of Scylfling and the Geatish house of Wulfling.[5]

Due to Beowulf and Norse sagas possibly independently mentioning some of the Swedish legendary royals some of them could be historical. Geats could have been a part of the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain. They probably did not have any major role but could have been described by English sources as Jutes.[6] The Wulfling dynasty in Geatland might be related to the house of Wuffingas.[7]

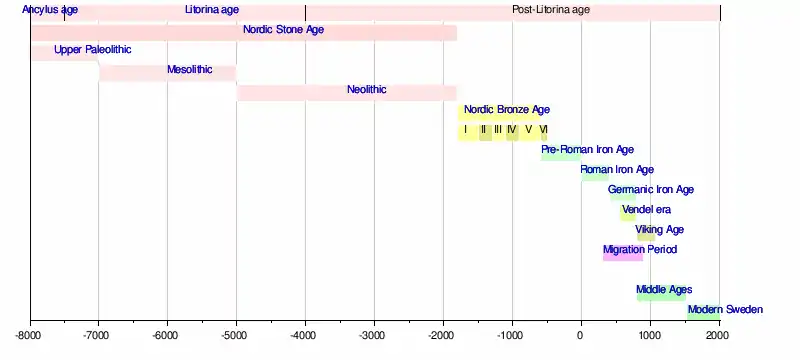

Timeline of Swedish history

References

- Harrison (2009), p. 68

- Harrison (2009), p 21-23

- Västhögen. "Västhögen". Arkeologi Gamla Uppsala (in Swedish). Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- Bruce-Mitford, Rupert (1974). Aspects of Anglo-Saxon Archaeology: Sutton Hoo and Other Discoveries. London: Victor Gollancz.

- https://www.gutenberg.org/files/16328/16328-h/16328-h.htm

- Schütte, Gudmund (1912). "The Geats of Beowulf". The Journal of English and Germanic Philology. 11 (4): 574–602. JSTOR 27700194.

- Newton, Sam (2004). The Origins of Beowulf: And the Pre-Viking Kingdom of East Anglia. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85991-472-7.

Sources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vendel era. |

- Jesch, Judith (ed.) (2012). The Scandinavians from the Vendel Period to the Tenth Century: An Ethnographic Perspective, Boydell Press, 2012. ISBN 9781843837282

- Harrison, Dick. Sveriges historia: 600-1350. Norstedts. Stockholm: 2009. ISBN 9789113023779

- Hyenstrand, Åke. Lejonet, draken och korset. Sverige 500–1000 [The Lion, the Dragon, and the Cross. Sweden 500–1000]. Enskede: TBP, 2002.