Union between Sweden and Norway

Sweden and Norway or Sweden–Norway (Swedish: Svensk-norska unionen; Norwegian: Den svensk-norske union(en)), officially the United Kingdoms of Sweden and Norway, or as the United Kingdoms, was a personal union of the separate kingdoms of Sweden and Norway under a common monarch and common foreign policy that lasted from 1814 until its peaceful dissolution in 1905.[3][4]

United Kingdoms of Sweden and Norway Förenade Konungarikena Sverige och Norge De forenede Kongeriger Norge og Sverige[upper-alpha 1] Sambandet millom Norig og Sverike[upper-alpha 2] | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1814–1905 | |||||||||||||||

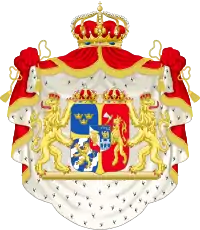

Royal Coat of Arms (1844-1905)

| |||||||||||||||

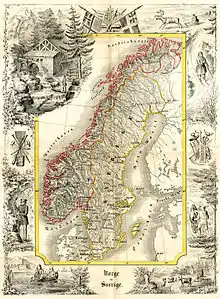

Sweden–Norway in 1904 | |||||||||||||||

| Status | Personal union | ||||||||||||||

| Capital | Stockholm and Christiania[a] | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Swedish, Norwegian,[b] Danish, Sami, Finnish | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Lutheranism | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchies | ||||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||||

• 1814–1818 | Charles XIII/II | ||||||||||||||

• 1818–1844 | Charles XIV/III John | ||||||||||||||

• 1844–1859 | Oscar I | ||||||||||||||

• 1859–1872 | Charles XV/IV | ||||||||||||||

• 1872–1905 | Oscar II | ||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Legislatures:[d] | ||||||||||||||

• Swedish legislature | Riksdag | ||||||||||||||

• Norwegian legislature | Storting | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | between Napoleonic Wars and World War I | ||||||||||||||

| 14 January 1814 | |||||||||||||||

| 4 November 1814 | |||||||||||||||

| 16 October 1875 | |||||||||||||||

| 26 October 1905 | |||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||

| 1905 | 774,184 km2 (298,914 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||

• 1820 | 3,550,000[c] | ||||||||||||||

• 1905 | 7,560,000[c] | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | Sweden:

Norway:

| ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||

a. ^ The king resided alternately in Stockholm (mostly) and Christiania (usually some months each year). He received ministers from both countries in Union council, or separately in purely Swedish or Norwegian councils. The majority of the Norwegian cabinet ministers convened in Christiania when the king was absent. b. ^ The written Norwegian language ceased to exist in the first half of the 16th century and was replaced by Danish. Written Danish was still used during the union with Sweden, but was slightly norwegianized through the creation of Nynorsk in the latter half of the 19th century. In 1885, the Storting accepted Landsmål as an official written language on par with Danish. | |||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Scandinavia |

|---|

The two states kept separate constitutions, laws, legislatures, administrations, state churches, armed forces, and currencies; the kings mostly resided in Stockholm, where foreign diplomatic representations were located. The Norwegian government was presided over by viceroys: Swedes until 1829, Norwegians until 1856. That office was later vacant and then abolished in 1873. Foreign policy was conducted through the Swedish foreign ministry until the dissolution of the union in 1905.

Norway had been in a closer union with Denmark, but Denmark-Norway's alliance with Napoleonic France caused the United Kingdom and Russia to consent to Sweden's annexation of the realm as compensation for the loss of Finland in 1809 and as a reward for joining the alliance against Napoleon. By the 1814 Treaty of Kiel, the King of Denmark-Norway was forced to cede Norway to the King of Sweden. But Norway refused to submit to the treaty provisions, declared independence, and convoked a constituent assembly at Eidsvoll in early 1814.

After the adoption of the new Constitution of Norway on 17 May 1814, Prince Christian Frederick was elected king. The ensuing Swedish–Norwegian War (1814) and the Convention of Moss compelled Christian Frederick to abdicate after calling an extraordinary session of the Norwegian Parliament, the Storting, to revise the Constitution in order to allow for a personal union with Sweden. On 4 November the Storting elected Sweden's king, Charles XIII, as the King of Norway, thereby confirming the union. Continuing differences between the two realms led to a failed attempt to create a separate Norwegian consular service and then, on 7 June 1905, to a unilateral declaration of independence by the Storting. Sweden accepted the union's dissolution on 26 October. After a plebiscite confirming the election of Prince Carl of Denmark as the new king of Norway, he accepted the Storting's offer of the throne on 18 November and took the regnal name of Haakon VII.

Background

Sweden and Norway had been united under the same crown on two previous occasions: from 1319 to 1343 and again briefly from 1449 to 1450 in opposition to Christian of Oldenburg who was elected king of the Kalmar Union by the Danes. During the following centuries, Norway remained united with Denmark in close union, nominally as one kingdom, but in reality reduced to the status of a mere province ruled by Danish kings from their capital, Copenhagen. After the establishment of absolutism in 1660, a more centralized form of government was established, but Norway kept some separate institutions, including its own laws, army, and coinage. The united kingdoms are referred to as Denmark-Norway by later historians.

Sweden broke out of the Kalmar Union permanently in 1523 under King Gustav Vasa, and in the middle of the 17th century rose to the status of a major regional power after the intervention of Gustavus II Adolphus in the Thirty Years' War. The ambitious wars waged by King Charles XII, however, led to the loss of that status after the Great Northern War, 1700–1721.

Following the dissolution of the Kalmar Union, Sweden and Denmark-Norway remained rival powers and fought many wars, during which both Denmark and Norway had to cede important provinces to Sweden in 1645 and 1658. Sweden also invaded Norway in 1567, 1644, 1658, and 1716 to wrest the country away from the union with Denmark and either annex it or form a union. The repeated wars and invasions led to popular resentment against Sweden among Norwegians.

During the eighteenth century, Norway enjoyed a period of great prosperity and became an increasingly important part of the union. The industry with the largest growth was that of the export of planks, with Great Britain as the chief market. Saw-mill owners and timber merchants in the Christiania region, backed by great fortunes and economic influence, formed an elite group that began to see the central government in Copenhagen as a hindrance to Norwegian aspirations. Their increasing self-assertiveness led them to question the policies that favored Danish interests over that of Norway's while rejecting key Norwegian demands for the creation of important national institutions, such as a bank and a university. Some members of the "timber aristocracy" thus saw Sweden as a more natural partner, and cultivated commercial and political contacts with Sweden. Around 1800, many prominent Norwegians secretly favored a split with Denmark, without actively taking steps to promote independence. Their undeclared leader was Count Herman Wedel-Jarlsberg.

The Swedish policy during the same period was to cultivate contacts in Norway and encourage all signs of separatism. King Gustav III (1746–1792) actively approached any circle in Norway that might favor a union with Sweden instead of with Denmark.

Such endeavors on both sides of the border toward a "rapprochement" were far from realistic before the Napoleonic Wars created conditions that caused great political upheavals in Scandinavia.

Consequences of the Napoleonic Wars

Sweden and Denmark-Norway strenuously attempted to remain neutral during the Napoleonic wars, and succeeded for a long time, in spite of many invitations to join the belligerent alliances. Both countries joined Russia and Prussia in a League of Armed Neutrality in 1800. Denmark-Norway was forced to withdraw from the League after the British victory at the First Battle of Copenhagen in April 1801, but still stuck to a policy of neutrality. However, the league collapsed after the assassination of Tsar Paul I in 1801.

Denmark-Norway was compelled into an alliance with France after the second British attack on the Danish navy at the Second Battle of Copenhagen. The Danish were forced to surrender the navy after heavy bombardment, because the army was at the southern border to defend it against a possible French attack. As Sweden in the meantime had sided with the British, Denmark-Norway was forced by Napoleon to declare war on Sweden on 29 February 1808.

Because the British naval blockade severed communications between Denmark and Norway, a provisional Norwegian government was set up in Christiania, led by army general Prince Christian August of Augustenborg. This first national government after several centuries of Danish rule demonstrated that home rule was possible in Norway, and was later seen as a test of the viability of independence. Christian August's greatest challenge was to secure the food supply during the blockade. When Sweden invaded Norway in the spring of 1808, he commanded the army of Southern Norway and compelled the numerically superior Swedish forces to withdraw behind the border after the battles of Toverud and Prestebakke. His success as a military commander and as leader of the provisional government made him very popular in Norway. Moreover, his Swedish adversaries noticed his merits and his popularity, and in 1809 chose him as successor to the Swedish throne after King Gustav IV Adolf was overthrown.

.jpg.webp)

One factor contributing to the poor performance of the Swedish invasion force in Norway was that Russia at the same time invaded Finland on 21 February 1808. The two-front war proved disastrous for Sweden, and all of Finland was ceded to Russia at the Peace of Fredrikshamn on 17 September 1809. In the meantime, discontent with the conduct of the war led to the deposition of King Gustav IV on 13 May 1809. Prince Christian August, the enemy commander who had been promoted to viceroy of Norway in 1809, was chosen because the Swedish insurgents saw that his great popularity among the Norwegians might open the way for a union with Norway, to compensate for the loss of Finland. He was also held in high esteem because he had refrained from pursuing the retreating army of Sweden while that country was hard pressed by Russia in the Finnish War. Christian August was elected Crown Prince of Sweden on 29 December 1809 and left Norway on 7 January 1810. After his sudden death in May 1810, Sweden chose as his successor another enemy general, the French marshal Jean Baptiste Bernadotte, who was also seen as a gallant adversary and had proved his ability as an army commander.

Sweden seeks compensation for the loss of Finland

The chief objective of Bernadotte's foreign policy as Crown Prince Charles John of Sweden was the acquisition of Norway, and he pursued that goal by definitively renouncing Sweden's claims in Finland and joining the enemies of Napoleon. In 1812, he signed the secret Treaty of Saint Petersburg with Russia against France and Denmark-Norway. His foreign policy provoked some criticism among Swedish politicians, who found it immoral to indemnify Sweden at the expense of a weaker friendly neighbor. Moreover, the United Kingdom and Russia insisted that Charles John's first duty was to the anti-Napoleonic coalition. Britain vigorously objected to the expenditure of her subsidies on the Norwegian adventure before the common enemy had been crushed. Only after Charles gave his word did the United Kingdom also promise to countenance the union of Norway and Sweden by the Treaty of Stockholm of 3 March 1813. Some weeks later, Russia gave her guarantee to the same effect, and in April Prussia also promised Norway as his prize for joining the battle against Napoleon. In the meantime, Sweden obliged its allies by joining the Sixth Coalition and declaring war against France and Denmark-Norway on 24 March 1813.

During his campaigns on the Continent, Charles John successfully led the Allied Army of the North in its defense of Berlin, defeating two separate French attempts to take the city, and at the decisive Battle of Leipzig. He then marched against Denmark to force the Danish King to surrender Norway.

1814

Treaty of Kiel

On 7 January, on the verge of being overrun by Swedish, Russian, and German troops under the command of the elected crown prince of Sweden, King Frederick VI of Denmark (and of Norway) agreed to cede Norway to the King of Sweden in order to stave off an occupation of Jutland.

These terms were formalized and signed on 14 January at the Treaty of Kiel, in which Denmark negotiated to maintain sovereignty over the Norwegian possessions of the Faroe Islands, Iceland and Greenland. Article IV of the treaty stated that Norway was ceded to "the King of Sweden", and not to the Kingdom of Sweden – a provision favorable to his former Norwegian subjects as well as to their future king, whose position as a former revolutionary turned heir to the Swedish throne was far from secure. Secret correspondence from the British government in the preceding days had put pressure on the negotiating parties to reach an agreement in order to avoid a full-scale invasion of Denmark. Bernadotte sent a letter to the governments of Prussia, Austria, and the United Kingdom, thanking them for their support, acknowledging the role of Russia in negotiating the peace, and envisaging greater stability in the Nordic region. On 18 January, the Danish king issued a letter to the Norwegian people, releasing them from their fealty to him.

Attempted coup d'état by Hereditary Prince Christian Frederik

Already in Norway, the viceroy of Norway, Hereditary Prince Christian Frederik resolved to preserve the integrity of the country, and if possible the union with Denmark, by taking the lead in a Norwegian insurrection. The king was informed of these plans in a secret letter of December 1813 and probably went along with them. But on the face of it, he adhered to the conditions of the Kiel Treaty by ordering Christian Frederik to surrender the border fortresses and return to Denmark. But Christian Frederik kept the contents of the letter to himself, ordering his troops to hold the fortresses. He decided to claim the throne of Norway as rightful heir, and to set up an independent government with himself at the head. On 30 January, he consulted several prominent Norwegian advisors, arguing that King Frederick had no legal right to relinquish his inheritance, asserting that he was the rightful king of Norway, and that Norway had a right to self-determination. His impromptu council agreed with him, setting the stage for an independence movement.

On 2 February the Norwegian public received the news that their country had been ceded to the King of Sweden. It caused a general indignation among most people, who disliked the idea of being subjected to Swedish rule, and enthusiastically endorsed the idea of national independence. The Swedish Crown Prince Bernadotte responded by threatening to send an army to occupy Norway, and to uphold the grain embargo, unless the country voluntarily complied with the provisions of the Kiel Treaty. In that case, he would call a constitutional convention. But for the time being, he was occupied with the concluding battles on the Continent, giving the Norwegians time to develop their plans.

The independence movement grows under threat of war

On 10 February, Christian Frederik invited prominent Norwegians to a meeting to be held at his friend Carsten Anker's estate at Eidsvoll to discuss the situation. He informed them of his intent to resist Swedish hegemony and claim the Norwegian crown as his inheritance. But at the emotional Eidsvoll session, his advisors convinced him that Norway's claim to independence should rather be based on the principle of self-determination, and that he should act as a regent for the time being. Back in Christiania on 19 February, Christian Frederik proclaimed himself regent of Norway. He ordered all congregations to meet on 25 February to swear loyalty to the cause of Norwegian independence and to elect delegates to a constitutional assembly to convene at Eidsvoll on 10 April.

The Swedish government immediately sent a mission to Christian Frederik, warning him that the insurrection was a violation of the Treaty of Kiel and put Norway at war with the allied powers. The consequences would be famine and bankruptcy. Christian Frederik sent letters through his personal network to governments throughout Europe, assuring them that he was not leading a Danish conspiracy to reverse the terms of the treaty of Kiel, and that his efforts reflected the Norwegian will for self-determination. He also sought a secret accommodation with Napoleon.

The Swedish delegation arrived in Christiania on 24 February. Christian Frederik refused to accept a proclamation from the Swedish king but insisted instead on reading his letter to the Norwegian people, proclaiming himself regent. The Swedes characterized his decisions as reckless and illegal, and returned to Sweden. The next day, church bells in Christiania rang for a full hour, and the city's citizens convened to swear fealty to Christian Frederik.

Carsten Anker was sent to London to negotiate recognition by the British government, with this instruction from the regent: "Our foremost need is peace with England. If, God forbid, our hope of English support is thwarted, you must make it clear to the minister what will be the consequences of leaving an undeserving people to misery. Our first obligation will then be the most bloody revenge upon Sweden and her friends; but you must never lose the hope that England will realize the unjustice that is being done to us, and voice it until the last moment – as well as our constant wish for peace." Anker's plea for support was firmly rejected by prime minister Lord Liverpool, but he persisted in his mission to convince his contacts among British aristocrats and politicians of Norway's cause. He succeeded in introducing that cause in Parliament, where Earl Grey spoke for almost three hours in the House of Lords on 10 May. His arguments were also voiced in the House of Commons – after having fought for freedom in Europe for 22 years, the United Kingdom could not go on to support Sweden in her forced subjugation of a free people then under a foreign yoke. But the Treaty between Britain and Sweden could not be ignored: Sweden had helped the allies during the war, and promises had to be kept. Anker stayed on in London until fall, doggedly maintaining his efforts to awaken sympathy and support for Norwegian interests.

By early March, Christian Frederik had also organized a cabinet and five government departments, though he retained all decision-making authority himself.

Christian Frederik meets increasing opposition

Count Wedel-Jarlsberg, the most prominent member of the Norwegian nobility, had been in Denmark to organize food supplies for the starving population while Prince Christian Frederik staged his insurrection. On his return trip he took time off to see Count Hans Henrik von Essen, newly appointed Swedish governor-general of Norway. When he arrived in March, he warned the regent that he was playing a dangerous game, but was himself accused of colluding with Sweden. Public opinion was increasingly critical of the policy of the regent, who was suspected of maneuvering to bring Norway back under Danish sovereignty.

On 9 March, the Swedish mission to Copenhagen demanded that Christian Frederik be disinherited from succession to the Danish throne and that European powers should go to war with Denmark unless he disassociated himself from the Norwegian independence movement. Niels Rosenkrantz, the Danish foreign minister, responded to the Swedish demands by asserting that the Danish government in no way supported Norwegian independence, but that they could not vacate border posts they did not hold. The demand to disinherit Christian Frederik was not addressed. Swedish troops massed along the border, and there were daily rumors of an invasion. In several letters to von Essen, commander of the Swedish forces at Norway's borders, Bernadotte referred to Christian Frederik as a rebel and ordered that all Danish officials who did not return home were to be treated as outlaws. But the regent countered by confiscating all navy vessels stationed in Norway and arresting officers who were planning to sail them to Denmark.

On 1 April, King Frederick VI of Denmark sent a letter to Christian Frederik, asking him to give up his efforts and return to Denmark. The possibility of disinheriting the Crown Prince was mentioned. Christian Frederik rejected the overture, invoking Norway's right to self-determination as well as the possibility of reuniting Norway and Denmark in the future. A few days later, Christian Frederik warned off a meeting with the Danish foreign minister, pointing out that it would fuel speculation that the prince was motivated by Danish designs on Norway.

Although the European powers refused to acknowledge the Norwegian independence movement, there were signs by early April that they were not inclined to side with Sweden in an all-out confrontation. As the constitutional convention drew closer, the independence movement gained in strength.

The constitutional convention

On 10 April, the delegates convened at Eidsvoll. Seated on uncomfortable benches, the convention elected its officers in the presence of Christian Frederik on 11 April, before the debates began the next day. Two parties were soon formed, the "Independence party", variously known as the "Danish party" or "the Prince's party", and on the other hand, the "Union party", also known as the "Swedish party". All delegates agreed that independence would be the ideal solution, but they disagreed on what was feasible.

- The Independence party had the majority and argued that the mandate was limited to formalizing Norway's independence based on the popular oath of fealty earlier that year. With Christian Frederik as regent, the relationship with Denmark would be negotiated within the context of Norwegian independence.

- The Union party, a minority of the delegates, believed that Norway would achieve a more independent status within a loose union with Sweden than as part of the Danish monarchy, and that the assembly should continue its work even after the constitution was complete.

The constitutional committee presented its proposals on 16 April, provoking a lively debate. The Independence party won the day with a majority of 78–33 to establish Norway as an independent monarchy. In the following days, mutual suspicion and distrust came to the surface within the convention. The delegates disagreed on whether to consider the sentiments of the European powers; some facts may have been withheld from them.

By 20 April, the principle of the people's right to self-determination articulated by Christian Magnus Falsen and Gunder Adler had been established as the basis of the constitution. The first draft of the constitution was signed by the drafting committee on 1 May. Key precepts of the constitution included the assurance of individual freedom, the right to property, and equality.

Following a contentious debate on 4 May, the assembly decided that Norway would adhere to the Lutheran faith, that its monarch must always have professed himself to this faith (thereby prevent the Catholic-born Bernadotte from being king) and that Jews and Jesuits would be barred from entering the kingdom. But the Independence party lost another battle when the assembly voted 98 to 11 to allow the monarch to reign over another country with the assent of two-thirds of the legislative assembly.

Although the final edict of the constitution was signed on 18 May, the unanimous election of Christian Frederik on 17 May is considered Constitution Day in Norway. The election was unanimous, but several of the delegates had asked that it be postponed until the political situation had stabilized.

Search for domestic and international legitimacy

On 22 May, the newly elected king made a triumphant entrance into Christiania. The guns of Akershus Fortress sounded the royal salute, and a celebratory service was held in the Cathedral. There was continuing concern about the international climate, and the government decided to send two of the delegates from the constitutional assembly to join Carsten Anker in England to plead Norway's case. The first council of state convened, and established the nation's supreme court.

On 5 June, the British emissary John Philip Morier arrived in Christiania on what appeared to be an unofficial visit. He accepted the hospitality of one of Christian Frederik's ministers and agreed to meet with the king himself informally, stressing that nothing he did should be construed as a recognition of Norwegian independence. It was rumored that Morier wanted Bernadotte deposed and exiled to the Danish island of Bornholm. The king asked the United Kingdom to mediate between Norway and Sweden, but Morier never deviated from the official British government position of rejecting an independent Norway. He stated that that Norway should subject itself to a Swedish union, and also that his government's position be printed in all Norwegian newspapers. On 10 June, the Norwegian army was mobilized and arms and ammunitions distributed.

On 16 June, Carsten Anker wrote to Christian Frederik about his recent discussions with a high-ranking Prussian diplomat. He learned that Prussia and Austria were waning in their support of Sweden's claims to Norway, that Tsar Alexander I of Russia (a distant cousin of Christian Frederik) favored a Swedish-Norwegian union but without Bernadotte as king, and that the United Kingdom was looking for a solution that would keep Norway out of Russia's sphere of influence.

Prelude to war

On 26 June, emissaries from Russia, Prussia, Austria, and the United Kingdom arrived in Vänersborg in Sweden to persuade Christian Frederik to comply with the provisions of the Treaty of Kiel. There they conferred with von Essen, who told them that 65,000 Swedish troops were ready to invade Norway. On 30 June the emissaries arrived in Christiania, where they turned down Christian Frederik's hospitality. Meeting with the Norwegian council of state the following day, the Russian emissary Orlov put the choice to those present: Norway could subject itself to the Swedish crown or face war with the rest of Europe. When Christian Frederik argued that the Norwegian people had a right to determine their own destiny, the Austrian emissary August Ernst Steigentesch made the famous comment: "The people? What do they have to say against the will of their rulers? That would be to put the world on its head."

In the course of the negotiations Christian Frederik offered to relinquish the throne and return to Denmark, provided the Norwegians had a say in their future through an extraordinary session of the Storting. However he refused to surrender the Norwegian border forts to Swedish troops. The four-power delegation rejected Christian Frederik's proposal that Norway's constitution form the basis for negotiations about a union with Sweden but promised to put the proposal to the Swedish king for consideration.

On 20 July, Bernadotte sent a letter to his "cousin" Christian Frederik, accusing him of court intrigues and foolhardy adventurism. Two days later he met with the delegation that had been in Norway. They encouraged him to consider Christian Frederik's proposed terms for a union with Sweden, but the Crown Prince was outraged. He reiterated his ultimatum that Christian Frederik either relinquish all rights to the throne and abandon the border posts or face war. On 27 July, a Swedish fleet took over the islands of Hvaler, effectively putting Sweden at war with Norway. The following day, Christian Frederik rejected the Swedish ultimatum, saying that surrender would constitute treason against the people. On 29 July, Swedish forces invaded Norway.

A short war with two winners

Swedish forces met little resistance as they advanced northward into Norway, bypassing the fortress of Fredriksten. The first hostilities were short and ended with decisive victories for Sweden. By 4 August, the fortified city of Fredrikstad surrendered. Christian Frederik ordered a retreat to the Glomma river. The Swedish Army, in trying to intercept the retreat, was stopped at the battle of Langnes, an important tactical victory for the Norwegians. The Swedish assaults from the east were effectively resisted near Kongsvinger.

On 3 August Christian Frederik announced his political will in a cabinet meeting in Moss. On 7 August, a delegation from Bernadotte arrived at the Norwegian military headquarters in Spydeberg with a ceasefire offer based on the promise of a union with respect for the Norwegian constitution. The following day, Christian Frederik expressed himself in favor of the terms, allowing Swedish troops to remain in positions east of Glomma. Hostilities broke out at Glomma, resulting in casualties, but the Norwegian forces were ordered to retreat. Peace negotiations with Swedish envoys began in Moss on 10 August. On 14 August, the Convention of Moss was concluded: a general ceasefire based effectively on terms of peace.

Christian Frederik succeeded in excluding from the text any indication that Norway had recognized the Treaty of Kiel, and Sweden accepted that it was not to be considered a premise of a future union between the two states. Understanding the advantage of avoiding a costly war, and of letting Norway enter into a union voluntarily instead of being annexed as a conquered territory, Bernadotte offered favorable peace terms. He promised to recognize the Norwegian Constitution, with only those amendments that were necessary to enable a union of the two countries. Christian Frederik agreed to call an extraordinary session of the Storting in September or October. He would then have to transfer his powers to the elected representatives of the people, who would negotiate the terms of the union with Sweden, and finally he would relinquish all claims to the Norwegian throne and leave the country.

An uneasy cease-fire

The news hit the Norwegian public hard, and reactions included anger at the "cowardice" and "treason" of the military commanders, despair over the prospects of Norwegian independence, and confusion about the country's options. Christian Frederik confirmed his willingness to abdicate the throne for "reasons of health", leaving his authority with the state council as agreed in a secret protocol at Moss. In a letter dated 28 August he ordered the council to accept orders from the "highest authority", implicitly referring to the Swedish king. Two days later, the Swedish king proclaimed himself the ruler of both Sweden and Norway.

On 3 September the British announced that the naval blockade of Norway was lifted. Postal service between Norway and Sweden was resumed. The Swedish general in the occupied border regions of Norway, Magnus Fredrik Ferdinand Björnstjerna, threatened to resume hostilities if the Norwegians would not abide by the armistice agreement and willingly accept the union with Sweden. Christian Frederik was reputed to have fallen into a deep depression and was variously blamed for the battleground defeats.

In late September, a dispute arose between Swedish authorities and the Norwegian council of state over the distribution of grain among the poor in Christiania. The grain was intended as a gift from the "Norwegian" king to his new subjects, but it became a matter of principle for the Norwegian council to avoid the appearance that Norway had a new king until the transition was formalized. Björnstjerna sent several missives threatening to resume hostilities.

Fulfilling the conditions of the Convention of Moss

In early October, Norwegians again refused to accept a shipment of corn from Bernadotte, and Norwegian merchants instead took up loans to purchase food and other necessities from Denmark. However, by early October, it was generally accepted that the union with Sweden was inevitable. On 7 October, an extraordinary session of the Storting convened. Delegates from areas occupied by Sweden in Østfold were admitted only after submitting assurances that they had no loyalty to the Swedish authorities. On 10 October, Christian Frederik abdicated according to the conditions agreed on at Moss and embarked for Denmark. Executive powers were provisionally assigned to the Storting, until the necessary amendments to the Constitution could be enacted.

One day before the cease-fire would expire, the Storting voted 72 to 5 to join Sweden in a personal union, but a motion to elect Charles XIII king of Norway failed to pass. The issue was set aside pending the necessary constitutional amendments. In the following days, the Storting passed several resolutions to assert as much sovereignty as possible within the union. On 1 November they voted 52 to 25 that Norway would not appoint its own consuls, a decision that later would have serious consequences. The Storting adopted the constitutional amendments that were required to allow for the union on 4 November and unanimously elected Charles XIII King of Norway, rather than acknowledging him as such.

The Union

The new king never set foot in his Norwegian kingdom, but his adopted heir Charles John arrived in Christiania on 18 November 1814. In his meeting with the Storting, he accepted the election and swore to uphold the constitution on behalf of the king. In his speech, the crown prince emphasized that the Union was a league that the king had entered into with the people of Norway, and that "he had chosen to take on the obligations that were of greater value to his heart, those that expressed the love of the people, rather than the privileges that were acquired through solemn treaties." His renouncement of the treaty of Kiel as the legal basis for the Union was endorsed by the Swedish Riksdag of the Estates in the preamble to the Act of Union on 15 August 1815. In order to understand the nature of the Union, it is necessary to know the historical events that led to its establishment. These demonstrate clearly that Sweden, aided by the major powers, forced Norway to enter the Union. On the other hand, Norway, aided by the same powers, essentially dictated the terms of the Union.

Seeds of discord were of course inherent in a constitutional association of two parties based on such conflicting calculations. Sweden saw the Union as the realization of an idea that had been nursed for centuries, one that had been strengthened by the recent loss of Finland. It was hoped that with time, the reluctant Norwegians would accept a closer relationship. The Norwegians, however, as the weaker party, demanded strict adherence to the conditions that had been agreed on, and jealously guarded the consistent observance of all details that confirmed the equality between the two states.[5]

An important feature of the Union was that Norway had a more democratic constitution than Sweden. The Norwegian constitution of 1814 adhered more strictly to the principle of separation of powers between the executive, legislative and judicial branches. Norway had a modified unicameral legislature with more authority than any legislature in Europe. In contrast, Sweden's king was a near-autocrat; the 1809 Instrument of Government stated unequivocally that "the king alone shall govern the realm." More (male) citizens in Norway (around 40%) had the right to vote than in the socially more stratified Sweden. During the early years of the Union, an influential class of civil servants dominated Norwegian politics; however, they were few in number, and could easily lose their grip if the new electors chose to take advantage of their numerical superiority by electing members from the lower social strata. To preserve their hegemony, civil servants formed an alliance with prosperous farmers in the regions. A policy conducive to agriculture and rural interests secured the loyalty of farmers. But with the constitutional provision that ⅔ of the members of parliament were to be elected from rural districts, more farmers would eventually be elected, thus portending a potential fracture in the alliance. Legislation that encouraged popular participation in local government culminated with the introduction of local self-government in 1837, creating the 373 rural Formannskapsdistrikt, corresponding to the parishes of the State Church of Norway. Popular participation in government gave more citizens administrative and political experience, and they would eventually promote their own causes, often in opposition to the class of civil servants.[6]

The increasing democratization of Norway would in time tend to drive the political systems of Norway and Sweden farther apart, complicate the cooperation between the two countries, and ultimately lead to the dissolution of the union between Norway and Sweden. For instance, while the king had the power of absolute veto in Sweden, he only had a suspending veto in Norway. Charles John demanded that the Storting grant him an absolute veto, but was forced to back down. While the constitution vested executive power in the King, in practice it came increasingly to rest in his Council of State (statsråd). A watershed in this process came in 1884, when Norway became the first Scandinavian monarchy to adopt parliamentary rule. After 1884, the king was no longer able to appoint a government entirely of his own choosing or keep it in office against the will of the Storting. Instead, he could only appoint members of the party or coalition having a majority in the Storting. The Council also became answerable to the Storting, so that a failed vote of confidence would cause the government to resign. By comparison, parliamentary rule was not established in Sweden until 1905—just before the end of the union.

The Act of Union

The lack of a common constitutional foundation for the Union was felt strongly by crown prince Charles John during its first year. The fundamental documents were only the Convention of Moss and the revised Norwegian constitution of 4 November 1814. But the conservative Swedish Riksdag had not allowed the Swedish constitution to be revised. Therefore, a bilateral treaty had to be negotiated in order to clarify procedures for treating constitutional questions that had to be decided jointly by both governments. The Act of Union (Riksakten) was negotiated during the spring of 1815, with prime minister Peder Anker leading the Norwegian delegation. The treaty contained twelve articles dealing with the king's authority, the relationship between the two legislatures, how the executive power was to be exercised if the king should die before the crown prince had attained majority, and the relationship between the cabinets. It also confirmed the practice of treating questions of foreign policy in the Swedish cabinet, with the Norwegian prime minister present. Vital questions pertaining to the Union were to be treated in a joint cabinet meeting, where all the Norwegian ministers in Stockholm would be present. The Act was passed by the Storting 31 July 1815 and by the Riksdag 6 August, and sanctioned by the king on 15 August. In Sweden the Act of Union was a set of provisions under regular law, but the Norwegian Storting gave it constitutional status, so that its provisions could only be revised according to the procedures laid down in the constitution.

The Union in practice

The conditions of the Union as laid down in the Convention of Moss, the revised Norwegian constitution, and the Act of Union, secured for Norway more independence than was intended in the Treaty of Kiel. To all appearances, Norway had entered the Union voluntarily and steadfastly denied Swedish superiority, while many Swedes saw Norway as an inferior partner and a prize of war.

Legally, Norway had the status of an independent constitutional monarchy, with more internal independence than it had enjoyed in over 400 years. While it shared a common monarch and a common foreign policy with Sweden, all other ministries and government institutions were separate from each state. Norway had its own army, navy and treasury. The foreign service was directly subordinate to the king, an arrangement that was embodied already in the Norwegian constitution of 17 May 1814, before the revision of 4 November. An unforeseen effect was that foreign policy was decided in the Swedish cabinet and conducted by the Swedish ministry of foreign affairs. When matters of foreign policy were discussed in cabinet meetings, the only Norwegian present who could plead Norway's case was the prime minister. The Swedish Riksdag could indirectly influence foreign policy, but not the Norwegian Storting. Because the representations abroad were appointed by the Swedish government and mostly staffed with Swedes, the Union was often seen by foreigners as functioning like a single state rather than two sovereign states. Over time, however, it became less common to refer to the union as "Sweden" and instead to jointly reference it as "Sweden and Norway".

According to the Norwegian constitution, the king was to appoint his own cabinet. Because the king mostly resided in Stockholm, a section of the cabinet led by the prime minister had to be present there, accompanied by two ministers. The first prime minister was Peder Anker, who had been prominent among the Norwegians who framed the constitution, and had openly declared himself to be in favor of the Union. The Norwegian government acquired a splendid town house, Pechlinska huset, as the residence of the cabinet section in Stockholm, which also served as an informal "embassy" of Norway. The other six Christiania-based ministers were in charge of their respective government departments. In the king's absence, meetings of the Christiania cabinet were chaired by the viceroy (stattholder), appointed by the king as his representative. The first to hold that office was count Hans Henrik von Essen, who had already at the conclusion of the Kiel treaty been appointed governor-general of Norway when the expected Swedish occupation would be effective.[7]

The next viceroys were also Swedes, and this consistent policy during the first 15 years of the Union was resented in Norway. From 1829 onwards, the viceroys were Norwegians, until the office was left vacant after 1856, and finally abolished in 1873.

Amalgamation or separation

After the accession of Charles John in 1818, he tried to bring the two countries closer together and to strengthen the executive power. These efforts were mostly resisted by the Norwegian Storting. In 1821, the king proposed constitutional amendments that would give him absolute veto, widened authority over his ministers, the right to rule by decree, and extended control over the Storting. A further provocation was his efforts to establish a new hereditary nobility in Norway. He put pressure on the Storting by arranging military maneuvers close to Christiania while it was in session. Nonetheless, all of his propositions were given thorough consideration, and then rejected. They were received just as negatively by the next Storting in 1824, and then shelved, save for the question of an extended veto. That demand was repeatedly put before every Storting during the king's lifetime to no avail.

The most controversial political issue during the early reign of Charles John was the question of how to settle the national debt of Denmark-Norway. The impoverished Norwegian state tried to defer or reduce the payment of 3 million speciedaler to Denmark, the amount that had been agreed upon. This led to a bitter conflict between the king and the Norwegian government. Though the debt was finally paid by means of a foreign loan, the disagreement that it had provoked led to the resignation of count Wedel-Jarlsberg as minister of finance in 1821. His father-in-law, prime minister Peder Anker, resigned soon after because he felt that he was mistrusted by the king.

The answer from Norwegian politicians to all royal advances was a strict adherence to a policy of constitutional conservatism, consistently opposing amendments that would extend royal power or lead to closer ties and eventual amalgamation with Sweden, instead favoring regional autonomy.

The differences and mistrust of these early years gradually became less pronounced, and Charles John's increasingly accommodating attitude made him more popular. After riots in Stockholm in the fall of 1838, the king found Christiania more convivial, and while there, he agreed to several demands. In a joint meeting of the Swedish and Norwegian cabinets on 30 January 1839, a Union committee with four members from each country was appointed to solve contested questions between them. When the Storting of 1839 convened in his presence, he was received with great affection by the politicians and the public.

National symbols

Another bone of contention was the question of national symbols – flags, coats of arms, royal titles, and the celebration of 17 May as the national day. Charles John strongly opposed the public commemoration of the May constitution, which he suspected of being a celebration of the election of Christian Frederik. Instead, but unsuccessfully, he encouraged the celebration of the revised constitution of 4 November, which was also the day when the Union was established. This conflict culminated with the Battle of the Square (torvslaget) in Christiania on 17 May 1829, when peaceful celebrations escalated into demonstrations, and the chief of police read the Riot Act and ordered the crowd to disperse. Finally, army and cavalry units were called in to restore order with some violence. The public outcry over this provocation was so great that the king had to acquiesce to the celebration of the national day from then on.

Soon after the Treaty of Kiel, Sweden had included the Coat of arms of Norway in the greater Coat of arms of Sweden. Norwegians considered it offensive that it was also displayed on Swedish coins and government documents, as if Norway was an integral part of Sweden. They also resented the fact that the king's title on Norwegian coins until 1819 was king of Sweden and Norway.[8] All of these questions were resolved after the accession of King Oscar I in 1844. He immediately began to use the title king of Norway and Sweden in all documents relating to Norwegian matters. The proposals of a joint committee with regard to flags and arm were enacted for both countries. A union mark was placed in the canton of all flags in both nations, combining the flag colours of both countries, equally distributed. The two countries obtained separate, but parallel flag systems, clearly manifesting their equality. Norwegians were pleased to find the former common war flag and naval ensign replaced by separate flags. The Norwegian arms were removed from the greater arms of Sweden, and common Union and royal arms were created to be used exclusively by the royal family, by the foreign service, and on documents pertaining to both countries. A significant detail of the Union arms is that two royal crowns were placed above the escutcheon to show that it was a union between two sovereign kingdoms.

Flags

State flag of Sweden (Pre-1814-1815)

State flag of Sweden (Pre-1814-1815).svg.png.webp) Flag of Norway (1814–1821)

Flag of Norway (1814–1821) Flag of Sweden and Norway (1818–1844)

Flag of Sweden and Norway (1818–1844).svg.png.webp) State flag and naval ensign of Sweden and Norway (1815–1844)

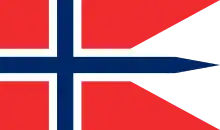

State flag and naval ensign of Sweden and Norway (1815–1844).svg.png.webp) Union naval jack and diplomatic flag (1844–1905)

Union naval jack and diplomatic flag (1844–1905).svg.png.webp) Flag of Sweden (1844–1905)

Flag of Sweden (1844–1905).svg.png.webp) Flag of Norway (1821–1844)

Flag of Norway (1821–1844) Flag of Norway (1844–1899)

Flag of Norway (1844–1899) Flag of Norway (1899–present)

Flag of Norway (1899–present).svg.png.webp) State flag and naval ensign of Sweden (1844–1905)

State flag and naval ensign of Sweden (1844–1905).svg.png.webp) Naval ensign of Norway (1844–1905) and state flag (1844–1899)

Naval ensign of Norway (1844–1905) and state flag (1844–1899) State flag of Norway (1899–present)

State flag of Norway (1899–present).svg.png.webp) Royal standard in Sweden (1844–1905)

Royal standard in Sweden (1844–1905).svg.png.webp) Royal standard in Norway (1844–1905)

Royal standard in Norway (1844–1905)

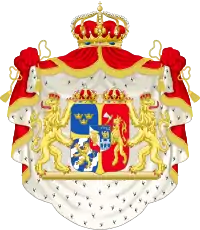

Heraldry

Royal Swedish coat of arms (1814–1844)

Royal Swedish coat of arms (1814–1844) Union and royal coat of arms (1844–1905)

Union and royal coat of arms (1844–1905)

Zenith of the Union, 1844–1860

The middle years of the 19th century were peaceful ones for the Union. All the symbolic questions had been settled, Norway had obtained more influence on foreign policy, the office of viceroy or governor was kept vacant or filled by Norwegian Severin Løvenskiold, and trade between the countries prospered from treaties (mellomriksloven) that promoted free trade and effectively abolished protective tariff walls. The completion of the Kongsvinger Line, the first railway connection across the border, greatly sped up communications. A political climate of conciliation was advanced by Swedish concessions on the issue of equality between the countries.

Scandinavism was at its height during this period and contributed to increasing rapprochement between the Union partners. It supported the idea of Scandinavia as a unified region or a single nation, based on the common linguistic, political, and cultural heritage of the Scandinavian countries. (These three countries are referred to as "three brothers" in the sixth stanza of the national anthem of Norway.) This elite movement was initiated by Danish and Swedish university students in the 1840s. In the beginning, the political establishments in the two countries were suspicious of the movement. However, when Oscar I became king of Sweden and Norway in 1844, the relationship with Denmark improved and the movement started to gain support. Norwegian students joined in 1845 and participated in annual meetings alternating between the countries. During the war between Denmark and Prussia in 1848, King Oscar offered support in the form of a Norwegian-Swedish expeditionary force, though the force never saw combat. The movement received a blow from which it never fully recovered after the second Danish-German war over Schleswig in 1864, when the Swedish and Norwegian governments jointly forced King Charles XV to retract the promise of military support that he had given to the king of Denmark without consulting his cabinets.[9]

By then, the Union had lost its support among Norwegians because of the setback caused by the issue of abolishing the office of viceroy. King Charles XV was in favor of this Norwegian demand, and after his accession in 1859 promised his Norwegian cabinet that he would sanction a decision of the Storting to this effect. The proposition to do away with this detested symbol of dependency and instead replace it with the office of a prime minister in Christiania was nearly unanimously carried. When the king returned to Stockholm, he was met by an unsuspectedly strong reaction from the Swedish nationalist press. Nya Dagligt Allehanda cried out that Norway had strayed from the path of lawfulness and turned toward revolution. The Riksdag demanded to have its say on the question. The crux of the matter was whether it was purely Norwegian or of concern to both countries. The conservative Swedish majority proclaimed Sweden's "rightful superior position in the Union". King Charles was forced to retreat when the Swedish cabinet threatened to resign. He chose not to sanction the law, but as a concession to wounded Norwegian sentiments, he did it anyway in a Norwegian cabinet meeting. But his actions had inadvertently confirmed that he was more Swedish than Norwegian, despite his good intentions.

On 24 April 1860, the Norwegian Storting reacted to the Swedish claim to supremacy by unanimously resolving that the Norwegian state had the sole right to amend its own constitution, and that any revision of the conditions of the Union had to be based on the principle of complete equality. This resolution would for many years block any attempts to revise the Act of Union. A new joint committee was appointed in 1866, but its proposals were rejected in 1871 because it did not provide for equal influence on foreign policy, and would pave the way for a federal state.[10]

Prelude to dissolution

The relations with Norway during the reign of King Oscar II (1872–1907) had great influence on political life in Sweden, and more than once it seemed as if the union between the two countries was on the point of ending. The dissensions chiefly had their origin in the demand by Norway for separate consuls and eventually a separate foreign service. Norway had, according to the revised constitution of 1814, the right to separate consular offices, but had not exercised that right partly for financial reasons, partly because the consuls appointed by the Swedish foreign office generally did a satisfactory job of representing Norway. During the late 19th century, however, Norway's merchant marine grew rapidly to become one of the world's largest, and one of the most important factors of the national economy. It was increasingly felt that Norway needed separate consuls who could assist shipping and national interests abroad. Partly, the demand for separate consuls also became a symbolic one, a way to assert the growing disillusionment with the Union.

In Norway, dissension on constitutional questions led to the de facto adoption of parliamentarism in 1884, after an impeachment process against the conservative cabinet of Christian August Selmer. The cabinet was accused of assisting the king in obstructing reform by veto. The new liberal government of Johan Sverdrup was reluctantly installed by King Oscar. It immediately implemented important reforms, among them extended suffrage and compulsory military service. The two opposite groups established formal political parties in 1884, Venstre (Left) for the liberals, who wanted to dissolve the Union, and Højre (Right) for conservatives, who wanted to retain a union of two equal states.

The liberals won a great majority in the elections of 1891 on a program of universal suffrage for all men and a separate Norwegian foreign service. As a first step, the new Steen government proposed separate consular services, and negotiations with Sweden were initiated. But royal opposition caused a series of cabinet crises until a coalition government was formed in 1895 with Francis Hagerup as prime minister. That year, the third joint Union committee was appointed, with seven members from each country, but it never agreed on crucial issues and was promptly disbanded in 1898. Faced with saber-rattling from militarily superior Sweden, Norway had to withdraw the demands for separate consuls in 1895. That miserable retreat convinced the government that the armed forces had been neglected too long, and rapid rearmament was initiated. Four battleships were ordered from the United Kingdom, and border fortifications were constructed.

In the midst of negotiations and discussions that were in vain, in 1895 the Swedish government gave notice to Norway that the current commercial treaty of 1874, which had provided for a promising common market, would lapse in July 1897. When Sweden reverted to protectionism, Norway also raised customs duties, and the result was a considerable diminution of trade across the border. Count Lewenhaupt, the Swedish minister of foreign affairs, who was considered to be too friendly towards the Norwegians, resigned and was replaced by Count Ludvig Douglas, who represented the opinion of the majority in the First Chamber. However, when the Storting in 1898 for the third time passed a bill for a "pure" flag without the Union badge, it became law without royal sanction.

The new elections to the Riksdag of 1900 showed clearly that the Swedish people were not inclined to follow the ultraconservative "patriotic" party, which resulted in the resignation of the two leaders of that party, Professor Oscar Alin and Court Marshal (Hofmarschall) Patric Reuterswärd as members of the First Chamber. On the other hand, ex-Professor E. Carlson, of the Gothenburg University, succeeded in forming a party of Liberals and Radicals to the number of about 90 members, who asides from being in favor of the extension of the franchise, advocated full equality of Norway with Sweden in the management of foreign affairs. The Norwegian elections of the same year with extended franchise gave the Liberals (Venstre) a great majority for their program of a separate foreign service and separate consuls. Steen stayed on as prime minister, but was succeeded by Otto Blehr in 1902.

Final attempts to save the Union

The question of separate consuls for Norway soon came up again. In 1902 foreign minister Lagerheim in a joint council of state proposed separate consular services, while keeping the common foreign service. The Norwegian government agreed to the appointment of another joint committee to consider the question. The promising results of these negotiations was published in a "communiqué" of 24 March 1903. It proposed that the relations of the separate consuls to the joint ministry of foreign affairs and the embassies should be arranged by identical laws, which could not be altered or repealed without the consent of the governments of both countries. But it was no formal agreement, only a preliminary sketch, not binding on the governments. In the elections of 1903, the Conservatives (Højre) won many votes with their program of reconciliation and negotiations. A new coalition government under Hagerup was formed in October 1903, backed by a national consensus on the need conclude the negotiations by joint action. The proposals of the communiqué were presented to the joint council of state on 11 December, raising hopes that a solution was imminent. King Oscar asked the governments to work out proposals for identical laws.

The Norwegian draft for identical laws was submitted in May 1904. It was met with total silence from Stockholm. While Norway had never had a Storting and a cabinet more friendly to the Union, it turned out that political opinion in Sweden had moved in the other direction. The spokesman for the communiqué, foreign minister Lagerheim, resigned on 7 November because of disagreement with prime minister Erik Gustaf Boström and his other colleagues. Boström now appeared on his own in Christiania and presented his unexpected principles or conditions for a settlement. His government had reverted to the stand that the Swedish foreign minister should retain control over the Norwegian consuls and, if necessary, remove them, and that Sweden should always be mentioned before Norway in official documents (a break with the practice introduced in 1844). The Norwegian government found these demands unacceptable and incompatible with the sovereignty of Norway. As the foreign minister was to be Swedish, he could not exercise authority over a Norwegian institution. Further negotiations on such terms would be purposeless.

A counter-proposal by the Swedish government was likewise rejected, and on 7 February 1905 the King in joint council decided to break off the negotiations that he had initiated in 1903. Notwithstanding this, the exhausted king still hoped for an agreement. On the next day Crown Prince Gustaf was appointed regent, and on 13 February appeared in Christiania to try to save the Union. During his month in Christiania, he had several meetings with the government and the parliamentary Special Committee that had been formed on 18 February to work out the details on national legislation to establish Norwegian consuls. He begged them not to take steps that would lead to a break between the countries. But to no avail, as the Special Committee recommended on 6 March to go ahead with the work in progress, and the conciliatory Hagerup cabinet was replaced with the more unyielding cabinet of Christian Michelsen.

Back in Stockholm on 14 March, Crown Prince Gustaf called a joint council on 5 April to appeal to both governments to return to the negotiation table and work out a solution based on full equality between the two kingdoms. He proposed reforms of both the foreign and consular services, with the express reservation that a joint foreign minister — Swedish or Norwegian — was a precondition for the existence of the Union. The Norwegian government rejected his proposal on 17 April, referring to earlier fruitless attempts, and declared that it would go on with preparations for a separate consular service. But both chambers of the Riksdag approved the proposal of the crown prince on 2 May 1905. In a last attempt to placate the recalcitrant Norwegians, Boström, considered to be an obstacle to better relations, was succeeded by Johan Ramstedt. But these overtures did not convince the Norwegians. Norwegians of all political convictions had come to the conclusion that a fair solution to the conflict was impossible, and there was now a general consensus that the Union had to be dissolved. Michelsen's new coalition cabinet worked closely with the Storting on a plan to force the issue by means of the consular question.

Dissolution of the Union

On 23 May the Storting passed the government's proposal for the establishment of separate Norwegian consuls. King Oscar, who again had resumed the government, made use of his constitutional right to veto the bill on 27 May, and according to plan, the Norwegian ministry tendered their resignation. The king, however, declared he could not accept their resignation, "as no other cabinet can now be formed". The ministers refused to obey his demand that they countersign his decision, and immediately left for Christiania.

No further steps were taken by the King to restore normal constitutional conditions. In the meantime, the formal dissolution was set to be staged at a sitting of the Storting on 7 June. The ministers placed their resignations in its hands, and the Storting unanimously adopted a planned resolution declaring the union with Sweden dissolved because Oscar had effectively "ceased to act as King of Norway" by refusing to form a new government. It further stated that, as the king had declared himself unable to form a government, the constitutional royal power "ceased to be operative." Thus, Michelsen and his ministers were instructed to remain in office as a caretaker government. Pending further instructions, they were vested with the executive power normally vested in the king pending the amendments necessary to reflect the fact that the union had been dissolved.

Swedish reactions to the action of the Storting were strong. The king solemnly protested and called an extraordinary session of the Riksdag for 20 June to consider what measures should be taken after the "revolt" of the Norwegians. The Riksdag declared that it was willing to negotiate the conditions for the dissolution of the Union if the Norwegian people, through a plebiscite, had declared themselves in favor. The Riksdag also voted for 100 million kronor to be available as the Riksdag might decide the matter. It was understood, but not openly stated, that the amount was held in readiness in case of war. The unlikely threat of war was seen as real on both sides, and Norway answered by borrowing 40 million kroner from France, for the same unstated purpose.

The Norwegian government knew in advance of the Swedish demands, and forestalled it by declaring a plebiscite for 13 August—before the formal Swedish demand for a plebiscite was made, thus forestalling any claim that the referendum was made in response to demands from Stockholm. The people were not asked to answer yes or no to the dissolution, but to "confirm the dissolution that had already taken place". The response was 368,392 votes for the dissolution and only 184 against, an overwhelming majority of over 99 percent. After a request from the Storting for Swedish cooperation to repeal the Act of Union, delegates from both countries convened at Karlstad on 31 August. The talks were temporarily interrupted along the way. At the same time, troop concentrations in Sweden made the Norwegian government mobilize its army and navy on 13 September. Agreement was nevertheless reached on 23 September. The main points were that disputes between the countries should in the future be referred to the permanent court of arbitration at The Hague, that a neutral zone should be established on both sides of the border, and that the Norwegian fortifications in the zone were to be demolished.

Both parliaments soon ratified the agreement and revoked the Act of Union on 16 October. Ten days later, King Oscar renounced all claims to the Norwegian crown for himself and his successors. The Storting asked Oscar to allow a Bernadotte prince to accede to the Norwegian throne in hopes of reconciliation, but Oscar turned this offer down. The Storting then offered the vacant throne to Prince Carl of Denmark, who accepted after another plebiscite had confirmed the monarchy. He arrived in Norway on 25 November 1905, taking the name Haakon VII.

1905 in retrospect

The events of 1905 put an end to the uneasy Union between Sweden and Norway that was entered into in 1814 — reluctantly by Norway, coerced by Swedish force. The events of both years have much in common, but there are significant differences:

- In 1814 the Norwegian struggle for independence was an upper-class borne project with scant popular support. In 1905 it was driven forward by popular consensus and elected representatives of the people.

- The Union of 1814 was the result of a Swedish initiative, while the dissolution of 1905 came about because Norway took the initiative.

- The crisis of 1814 was triggered because Sweden saw Norway as legitimate booty of war and as compensation for the loss of Finland in 1809, while Norway based its claim to independence on the principle of popular sovereignty. It was resolved because of wise and statesmanlike conduct by the leaders on both sides. The crisis of 1905 was caused by the rise of nationalism during the late 19th century, while the opposite interpretations of the Union still had a wide and increasing following in both countries.

- In 1814 Norway was the most industrialized and commercialized country in Scandinavia, despite its rather recent government institutions. In 1905 Norway was a well-developed state with 91 years experience of independent government since the union with Denmark. Its armed forces were no longer as heavily outnumbered in comparison with those of Sweden.

- The great powers viewed Norwegian independence more favorably in 1905 than in 1814.

See also

Notes

- In written Danish, the predecessor of Bokmål. The union act (Danish: Rigsakten) uses the term Foreningen imellem Norge og Sverige (i.e. "The Union between Norway and Sweden").

- In written Landsmål, the predecessor of Nynorsk, a co-official language since 1885. Though the union had no official name in Landsmål, terms such as Sambandet (or Samfestet or Samlaget) millom Norig og Sverike (including variations) were in use (all loosely translate to "The Union between Norway and Sweden"). Samfestet millom Norig og Sverike was the term used by the prominent Landsmål author Aasmund Olavsson Vinje, while Olav Jakobsen Høyem used Sambande millom Noreg og Sverige in his 1879 translation of the union act. In this translation the united throne is called Dei einade kongsstolarne i Noreg og Sverige ("The united thrones of Norway and Sweden").

References

- "Skandinaviens befolkning".

- "SSB – 100 års ensomhet? Norge og Sverige 1905–2005 (in Norwegian)". Archived from the original on November 19, 2014.

- "Sweden". World Statesmen. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- "Norway". World Statesmen. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- Hertzberg, E., 1906: "Unionen". In: Salmonsens Konversationsleksikon, Vol. XVII, p. 1043, Copenhagen

- Dyrvik. S. and Feldbæk, O., 1996: Mellom brødre 1780–1830. In: ' 'Aschehougs Norges Historie' ', Vol. 7, pp. 227–28, Oslo ISBN 978-82-03-22020-3

- Frydenlund, Bård, 2009: Stormannen Peder Anker. En biografi., pp. 254, 263, Oslo. ISBN 978-82-03-21084-6

- Seip, Anne-Lise, 1997: Nasjonen bygges 1830–1870. In: ' 'Aschehougs Norges Historie' ', Vol. 8, pp. 192–93, Oslo. ISBN 978-82-03-22021-0

- Seip, Anne-Lise, 1997: "Nasjonen bygges 1830–1870". In: Aschehougs Norges Historie, Vol. 8, pp. 199–201, Oslo. ISBN 978-82-03-22021-0

- Seip, Anne-Lise, 1997: "Nasjonen bygges 1830–1870". In: Aschehougs Norges Historie, Vol. 8, pp. 201–203, Oslo. ISBN 978-82-03-22021-0

Further reading

- Barton, H. Arnold. Sweden and Visions of Norway: Politics and Culture, 1814-1905 (SIU Press, 2003).

- Stråth, Bo (2005): Union och demokrati: de förenade rikena Sverige och Norge 1814–1905. Nora, Nya Doxa. ISBN 91-578-0456-7 (Swedish edition)

- Stråth, Bo (2005): Union og demokrati: Dei sameinte rika Noreg-Sverige 1814–1905. Oslo, Pax Forlag. ISBN 82-530-2752-4 (Norwegian edition)

- Gosse, Edmund William (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 809.

- Gosse, Edmund William (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 210.

External links

- "Debating the Treaty of Stockholm, 3d March 1813", hosted at the University of Oslo and including the texts of the Treaties of Stockholm (1813) and St. Petersburg (1813)

- "Treaty between Her Majesty, the Emperor of the French, and the King of Sweden and Norway. Signed at Stockholm, November 21, 1855", hosted at Google Books (in French) &