Vexator Canadiensis tokens

The Vexator Canadiensis tokens (also known as the Vexator Canadensis tokens) are thought to be politically satirical tokens produced in either Quebec City or Montreal sometime in the 1830s.[1] The tokens present a very crude image of a vaguely male bust on their obverse, and a female figure on the reverse. The legends on either side were deliberately designed so that they are hard to definitively read, but are commonly known as the "vexators" based on a common interpretation of its obverse legend.[2] Depending on the interpretation of the inscriptions, they can either be taken as a form of satirical protest against either an unpopular Upper Canada governor or William IV as a "tormentor of Canada", or more simply, depicting a fur trapper.[3] Since both interpretations are possible, this ambiguity would allow the issuer from escaping being cited for sedition.[4]

Despite the date of 1811 (or for one unique version, 1810), appearing on its reverse, it has long been thought to have been issued sometime in the 1830s, the backdating serving as a way to circumvent regulations against importing contemporary tokens.[5] At least three main varieties are known,[6] though additional die variations are known to exist. Recent numismatic scholarship has questioned the long-standing assumption that the tokens were issued in the 1830s, and may have in fact been issued closer to the date that appears on them.[7] They were not produced in large numbers, and typical examples start at several hundred C$ and up.[8]

Description

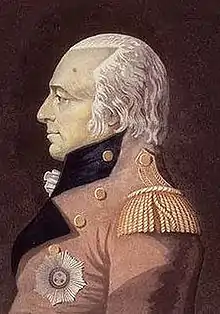

The obverse depicts the bust of man, looking left, with wavy hair and what has been described as a "shaggy" appearance.[9] It obverse legend can be read as saying either VEXATOR or VENATOR CANADIENSIS, a Latin description that can be interpreted as "Tormentor of Canada/Pest of Canada" or "A Canadian Trapper" respectively.[10] The legend is crudely cut, with reversed "N"s in CANADIENSIS,[11] and the third letter of the first word can be interpreted as being either an "X" or an "N".[12] Some descriptions of the bust on the obverse say that it has a "protruding tongue".[13] A variation of the obverse includes a small star at the bottom of the bust.[14]

The reverse features a crude-looking seated female figure (likely a depiction of Britannia),[15] surrounded by the legend RENONILLOS VISCAPE, with the date 1811 (or much less commonly, 1810), appearing at the bottom.[16] One interpretation of the legend is: "Wouldn't you like to catch them?".[17] A single five-pointed star typically appears between the two words in the legend, though one variation has three stars.[18]

These tokens are struck in both copper and brass, and have a wide range of weight, from as little as 45 grains to 100 grains (3 g to 6.5 g),[19] with at least one example weighing 126 grains (8 g).[20]

Numismatic Study

Early Studies

The vexators were first described by Alfred Sandham in his Coins, Tokens and Medal of the Dominion of Canada from 1869. He took the date on the token at face value, and therefore considered this token to be the first to be created and struck within Canada, as opposed to being imported from outside the country.[21] Sandham described three examples in his catalog (numbers 5, 6, and 7 under the "Canada" chapter), though he mentions that he was aware of additional varieties, differing "in the mode of spelling, or in punctuation".[22] He interpreted the female figure on the reverse of the token to be "dancing".[23]

A subsequent study of the vexators followed in 1874 with the publication of A Canadian Political Coin by William Kingsford. The majority of this monograph focuses on the political background of Upper Canada in the 1810s that he thought led to the issuing of this satirical token, though he mentions that the majority of these tokens had been found in Quebec City, and was the first to interpret the reverse legend as saying "Don't you wish you may catch them?"[24] Based on the date appearing on the tokens, Kingsford believed the "tormentor of Canada" being targeted was Sir James Craig, who was governor of Upper Canada up until that year.[25] This story was picked up by Pierre-Napoléon Breton in his illustrated catalog of Canadian numismatics from 1894, who also goes into the dictatorial nature of Sir James Craig's colonial rule when describing the historical background for these tokens. Breton also mentions that all of the specimens of these tokens he had encountered were "poorly struck, and it is impossible to find any in good condition".[26] While Sandham mentioned three distinct varieties, Breton only lists two, which he cataloged as numbers 558 and 559, while also noting that each had its own variations.[27] Using a 10-point scale (where 10 is rarest), Breton described these tokens as having a rarity level of "R3", though noting that "they are becoming rare."[28]

In 1910, American numismatist Howland Wood discovered a variety of the vexators featuring an obverse having a larger head, no legend, and the date "1810" on it.[29] The reverse, which he described as "being the variety with the dress of the female figure looking as if it was made of feathers", otherwise matching that of Breton 558, including the date 1811.[30] He speculated that perhaps this token indicated that the idea for the vexators had started prior to the departure of Sir John Craig, or that the obverse was the result of an experimental die pressed into makeshift service.[31] No other vexator with the date 1810 has appeared since Wood's discovery, and it is now considered to be "probably unique".[32] This piece is now part of the Bank of Canada collection.[33]

The most comprehensive early study of the vextor tokens came from numismatist R. W. McLachlan in his article When Was the Vexator Canadensis Issued?, published in 1915. He had reviewed 25-30 specimens of the vexator tokens personally, and could only find the two major variants matching those described by Breton.[34] He consequently believed that the three main varieties noted by Sandham to be in error, believing that published work to have been "prepared in haste without proper examination of the pieces described".[35] McLachlan consulted with two Latin experts who both concurred that Kingsford's interpretation of the Latin inscription renunilos viscape as to say "Non illos vis capere" ("Don't you wish you may catch them?"), on the reverse was correct.[36] Given the light weight of these tokens, McLachlan believed that they would not have been accepted as halfpenny coins as early as 1811, and that there was no evidence of any coins being struck in Canada at such an early date.[37] That situation had changed by the 1830s when other lightweight tokens, including the Blacksmith tokens, which McLachlan believed the vexator tokens resembled,[38] and whose confusing legend echoed those found on Blacksmith or similar evasion tokens.[39] He also noted that many of the tokens struck for use in Lower Canada in the mid-1830s were antedated, including the Tiffin tokens dated to 1812, the Harp tokens to 1820 and to British halfpence that were first issued in the 1730s, during the reign of George II.[40] Finding examples of the tokens to be as common in Montreal as in Quebec City, he believed that they were more likely to have been manufactured in Montreal, and no earlier than 1835.[41] McLachlan further concluded that the "tormentor" being singled out was likely to be William IV, and that while the issuer wanted to secretly satirize the administration of Lower Canada from a French Canadian standpoint, the primary motivation was profit by issuing undervalued tokens for circulation.[42]

An analysis of the legends on the vexator tokens from the mid-1960s concluded that it was probable that whoever designed the tokens was likely a numismatist, as they must have been familiar with the blundered legends of similar evasion currency from the United States and England, and that only a well-educated person would be able to "devise such a piece and compose an original legend in Latin".[43]

Modern Studies

A modern catalog on Canadian colonial tokens recognizes three distinct varieties of the vexator tokens, including variants issued in either copper or brass.[44] Additional variants, including two distinct uniface examples, have since appeared.[45][46]

McLachlan's landmark article on the vexators has been re-examined in more recent times, calling into question their supposed relation to Blacksmith tokens, whether they were issued in the 1830s as McLachlan thought,[47] and even whether they were intended to circulate at all.[48] Numismatist Wayne Jacobs re-examined the history and studies on the vexator tokens in a 1996 article, and proposed that the vexators were in fact meant as a "lodge pass" for members of The Brotherhood of Hunters, and were never intended for circulation, but to identify a member of the lodge.[49]

X-ray fluorescence have found that two of the vexator varieties are identical in their elemental composition, suggesting that they were made at the same time or at least came from the same stock of copper blanks.[50]

The total number of vexator tokens available to modern collectors has been estimated to be between 300-400.[51]

Notes

- Willey p 122

- Willey p 122

- Willey p 122

- Willey p 123

- Cross p 204

- Willey p 123

- Mayhugh p 37

- Heritage p 81-82

- Willey p 123

- Willey p 122-123

- Willey p 123

- Cross p 204

- Heritage p 81

- Heritage p 81

- Heritage p 81

- Willey p 123

- Cross p 204

- Heritage p 82

- Willey p 123

- Mayhugh p 38

- Sandham p 7

- Sandham p 21

- Sandham p 21

- Kingsford p 5

- Kingsford p 6

- Breton1894 p 61

- Breton1894 p 60-62

- Breton1894 p 61

- Wood p 233

- Wood p 233

- Wood p 233

- Jacobs p 62

- Jacobs p 62

- McLachlan1915 p 94

- McLachlan1915 p 94

- McLachlan1915 p 97-98

- McLachlan1915 p 99

- McLachlan1915 p 100

- McLachlan1915 p 102

- McLachlan1915 p 101

- McLachlan1915 p 102-103

- McLachlan1915 p 102-103

- Willey1969 p 115

- Cross p 205

- Mayhugh p 36

- Jacobs p 61

- Mayhugh p 37

- Mayhugh p 39

- Jacobs p 69

- Lorenzo p 241

- Kleeberg p 202

Bibliography

- Breton, P. N. (1894). Illustrated History of Coins and Tokens Relating to Canada. P.N. Breton & Co.

- Cross, W. K. (2012). Canadian Colonial Tokens, 8th Edition. The Charlton Press. ISBN 978-0-88968-351-8.

- Heritage World and Ancient Coins: The Doug Robins Collection of Canadian Tokens. Chicago: Heritage Numismatic Auctions, Inc. April 20, 2018.

- Jacobs, Wayne L. (March 1996). "The Vexator Riddle". The Canadian Numismatic Journal. 41 (2): 61–75.

- Kingsford, William (1874). A Canadian Political Coin. Ottawa: E. A. Perry.

- Kleeberg, John M., ed. (2000). Circulating Counterfeits of the Americas. American Numismatic Society.

- Lorenzo, John (2017). Forgotten Coins of the North American Colonies - 25th Anniversary edition. Amazon Books.

- Mayhugh, Marc (Summer 2008). "The Vexator". The C4 Newsletter. 16 (2): 36–40.

- McLachlan, R. W. (April 1915). "When Was the Vexator Canadensis Issued?". The Canadian Antiquarian and Numismatic Journal.

- Sandham, Alfred (1869). Coins, Tokens and Medal of the Dominion of Canada. Montreal: Daniel Rose.

- Willey, Robert C. (2011). The Annotated Colonial Coinages of Canada. PetchNet.

- Willey, R. C. (April 1969). "The History of Canadian Numismatics". The Canadian Numismatic Journal. 14 (4): 115.

- Wood, Howland (Oct–Nov 1910). "New Variety of The Vexator Canadinsis Piece". The Numismatist. 23: 233.

External links

- Illustrated History of Coins and Tokens Relating to Canada, by P. N. Breton, on Archive.org

- When Was the Vexator Canadensis Issued?, by R. W. McLachlan, on Archive.org

- Coins, tokens and medals of the Dominion of Canada, by Alfred Sandham, on Archive.org

- [https://archive.org/details/TheNumismatist1910Vol23/page/n237 "New Variety of the Vexator Canadinsis Piece", by Howland Wood, The Numismatist, on Archive.org

- Examples of vexator tokens from the Bank of Canada Museum's National Currency Collection