Victorian decorative arts

Victorian decorative arts refers to the style of decorative arts during the Victorian era. Victorian design is widely viewed as having indulged in a grand excess of ornament. The Victorian era is known for its interpretation and eclectic revival of historic styles mixed with the introduction of middle east and Asian influences in furniture, fittings, and interior decoration. The Arts and Crafts movement, the aesthetic movement, Anglo-Japanese style, and Art Nouveau style have their beginnings in the late Victorian era and gothic period.

Architecture

Interior decoration and design

Interior decoration and interior design of the Victorian era are noted for orderliness and ornamentation. A house from this period was idealistically divided in rooms, with public and private space carefully separated. The parlour was the most important room in a home and was the showcase for the homeowners where guests were entertained. A bare room was considered to be in poor taste, so every surface was filled with objects that reflected the owner's interests and aspirations. The dining room was the second-most important room in the house. The sideboard was most often the focal point of the dining room and very ornately decorated.

Vanderbilt Mansion, living room

Vanderbilt Mansion, living room 1879, parlor of Emlen Physick Estate, 1048 Washington Street, New Jersey

1879, parlor of Emlen Physick Estate, 1048 Washington Street, New Jersey Lanhydrock House, drawing room

Lanhydrock House, drawing room Dunedin Club, interior, billiard room

Dunedin Club, interior, billiard room

Walls and ceilings

The choice of paint color on the walls in Victorian homes was said to be based on the use of the room. Hallways that were in the entry hall and the stair halls were painted a somber gray so as not to compete with the surrounding rooms. Most people marbleized the walls or the woodwork. Also on walls it was common to score into wet plaster to make it resemble blocks of stone. Finishes that were either marbleized or grained were frequently found on doors and woodwork. "Graining" was meant to imitate woods of higher quality that were more difficult to work. There were specific rules for interior color choice and placement. The theory of “harmony by analogy” was to use the colors that lay next to each other on the color wheel. And the second was the “harmony by contrast” that was to use the colors that were opposite of one another on the color wheel. There was a favored tripartite wall that included a dado or wainscoting at the bottom, a field in the middle and a frieze or cornice at the top. This was popular into the 20th century. Frederick Walton who created linoleum in 1863 created the process for embossing semi-liquid linseed oil, backed with waterproofed paper or canvas. It was called Lincrusta and was applied much like wallpaper. This process made it easy to then go over the oil and make it resemble wood or different types of leather. On the ceilings that were 8–14 feet the color was tinted three shades lighter than the color that was on the walls and usually had a high quality of ornamentation because decorated ceilings were favored.

Furniture

There was not one dominant style of furniture in the Victorian period. Designers rather used and modified many styles taken from various time periods in history like Gothic, Tudor, Elizabethan, English Rococo, Neoclassical and others. The Gothic and Rococo revival style were the most common styles to be seen in furniture during this time in history.

Albert Chevallier Tayler The Grey Drawing Room

Albert Chevallier Tayler The Grey Drawing Room Albert Chevallier Tayler The Quiet Hour

Albert Chevallier Tayler The Quiet Hour Breakfast by Albert Chevallier Tayler 1909

Breakfast by Albert Chevallier Tayler 1909 Christmas tree decoration by Marcel Rieder (1862-1942)

Christmas tree decoration by Marcel Rieder (1862-1942)

Wallpaper

Wallpaper and wallcoverings became accessible for increasing numbers of householders with their wide range of designs and varying costs. This was due to the introduction of mass production techniques and, in England, the repeal in 1836 of the Wallpaper tax introduced in 1712.

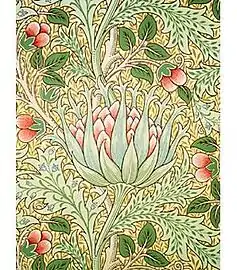

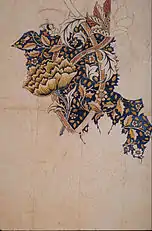

Wallpaper was often made in elaborate floral patterns with primary colors (red, blue, and yellow) in the backgrounds and overprinted with colours of cream and tan. This was followed by Gothic art inspired papers in earth tones with stylized leaf and floral patterns. William Morris was one of the most influential designers of wallpaper and fabrics during the latter half of the Victorian period. Morris was inspired and used Medieval and Gothic tapestries in his work. Embossed paper were used on ceilings and friezes.

Artichoke wallpaper, by John Henry Dearle for Morris & Co., circa 1897 (Victoria and Albert Museum).

Artichoke wallpaper, by John Henry Dearle for Morris & Co., circa 1897 (Victoria and Albert Museum). Acanthus wallpaper, 1875

Acanthus wallpaper, 1875 Snakeshead printed textile, 1876

Snakeshead printed textile, 1876 Peacock and Dragon woven wool furnishing fabric, 1878

Peacock and Dragon woven wool furnishing fabric, 1878 Design for Windrush printed textile, 1881–83

Design for Windrush printed textile, 1881–83 Detail of Woodpecker tapestry, 1885

Detail of Woodpecker tapestry, 1885

Old interiors

Dining room of the Theodore Roosevelt Sr. townhouse, New York City (1873, demolished).

Dining room of the Theodore Roosevelt Sr. townhouse, New York City (1873, demolished). Victorian style dining room, USA,

Victorian style dining room, USA,

early 1900s. Victorian style parlor, USA, early 1900s

Victorian style parlor, USA, early 1900s Room with Victorian design, early 1900s

Room with Victorian design, early 1900s Parlor in a New York House from the 1850s.

Parlor in a New York House from the 1850s. The parlor of the Whittemore House 1526 New Hampshire Avenue, Dupont Circle, Washington, D.C

The parlor of the Whittemore House 1526 New Hampshire Avenue, Dupont Circle, Washington, D.C

Preserved interiors

1890s Bedroom, James A. Garfield National Historic Site

1890s Bedroom, James A. Garfield National Historic Site Victorian bedroom exhibition, Dalgarven Mill, Ayrshire

Victorian bedroom exhibition, Dalgarven Mill, Ayrshire The Victorian sittingroom

The Victorian sittingroom Victorian kitchen, Dalgarven Mill, Ayrshire

Victorian kitchen, Dalgarven Mill, Ayrshire Victorian kitchen, Dalgarven

Victorian kitchen, Dalgarven Workhouse schoolroom

Workhouse schoolroom

Oscar Wilde's Aesthetic of Victorian Decoration

Chief among the literary practitioners of decorative aestheticism was Oscar Wilde, who advocated Victorian decorative individualism in speech, fiction, and essay-form.[1] Wilde’s notion of cultural enlightenment through visual cues echoes that of Alexandre von Humboldt[2] who maintained that imagination was not the Romantic figment of scarcity and mystery but rather something anyone could begin to develop with other methods, including organic elements in pteridomania[[3]].

By changing one’s immediate dwelling quarters, one changed one’s mind as well[[4]]; Wilde believed that the way forward in cosmopolitanism began with as a means eclipse the societally mundane, and that such guidance would be found not in books or classrooms, but through a lived Platonic epistemology.[5] An aesthetic shift in the home’s Victorian decorative arts reached its highest outcome in the literal transformation of the individual into cosmopolitan, as Wilde was regarded and noted among others in his tour of America.[6]

For Wilde, however, the inner meaning of Victorian decorative arts is fourfold: one must first reconstruct one’s inside so as to grasp what is outside in terms of both living quarters and mind, whilst hearkening back to von Humboldt on the way to Plato so as to be immersed in contemporaneous cosmopolitanism,[7] thereby in the ideal state becoming oneself admirably aesthetical.

See also

- Victorian fashion

- Victoriana

- Eastlake Movement

- French polish

- Neo-Victorian

- Pteridomania

- Staffordshire dog figurine

- Charles Eastlake, Victorian designer

- Augustus Pugin, Victorian designer

- William Morris wallpaper designs

References

- van der Plaat, Deborah (2015). "Visualising the Critical: Artistic Convention and Eclecticism in Oscar Wilde's Writings on the Decorative Arts". Australasian Journal of Victorian Studies. 19 (1): 9–10.

- van der Plaat, Deborah (2015). "Visualising the Critical: Artistic Convention and Eclecticism in Oscar Wilde's Writings on the Decorative Arts". Australasian Journal of Victorian Studies. 19 (1): 1–2, 12.

- Flanders, Judith (2002). Inside the Victorian Home. New York: W.W. Norton & Co. pp. 200–02.

- van der Plaat, Deborah (2015). "Visualising the Critical: Artistic Convention and Eclecticism in Oscar Wilde's Writings on the Decorative Arts". Australasian Journal of Victorian Studies. 19 (1): 11–14.

- van der Plaat, Deborah (2015). "Visualising the Critical: Artistic Convention and Eclecticism in Oscar Wilde's Writings on the Decorative Arts". Australasian Journal of Victorian Studies. 19 (1): 11–16.

- Blanchard, Mary W. (1995). "Boundaries and the Victorian Body: Aesthetic Fashion in Gilded Age America". The American Historical Review. 100 (1): 39–45.

- Monsman, Gerald (2002). "The Platonic Eros of Walter Pater and Oscar Wilde: Love's Reflected Image in the 1890s". English Literature in Transition. 45 (1): 26–9.

External links

![]() Media related to Victorian era at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Victorian era at Wikimedia Commons

- Victorian Furniture

- Victorian Room Virtual Tour

- Victorian Design (victorianweb.org) including ceramics, furniture, glass, jewelry, metalwork, and textiles.

- Early Victorian Furniture History in England

- Interior decoration and design

- Floral Wallpaper

- Late Victorian Era Furniture History in England

- Victorian Bookmarks

- Mostly-Victorian.com - Arts, crafts and interior design articles from Victorian periodicals.

- "Victorian Furniture Styles". Furniture. Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 2010-11-19. Retrieved 2011-04-03.

- The history of wallcoverings and wallpaper

- Interior design: Victorian - National Trust