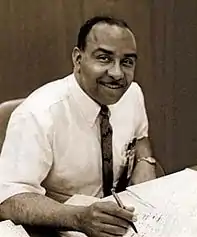

W. Harry Davis

William Harry Davis, Sr. (April 12, 1923 – August 11, 2006) was an American civil rights activist, amateur boxing coach, civic leader, and businessman in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He overcame poverty, childhood polio, and racial prejudice to become a humanitarian. Davis is remembered for his warm and positive personality, for coaching Golden Gloves champions in the upper Midwest, and for managing the Olympics boxing team that won nine gold medals. His contributions to public education in his community are enduring. A leader in desegregation during the Civil Rights Movement, Davis helped Americans find a way forward to racial equality.

W. Harry Davis | |

|---|---|

Davis published his memoirs in 2002 and 2003. | |

| Born | April 12, 1923 Minneapolis, Minnesota, U.S. |

| Died | August 11, 2006 (aged 83) |

| Occupation | Civic leader, businessman, boxing coach |

| Employer | Onan, Star Tribune, Cowles Media Company |

| Known for | Civil rights activism, desegregation, Golden Gloves boxing, public education |

| Political party | Minnesota Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party |

| Spouse(s) | Charlotte Davis |

| Children | Rita Lyell, Harry Davis Jr., Richard Davis, Evan Davis |

Biography

Early years

Davis was the son of Elizabeth Jackson, known as Libby, and Lee Davis, a Winnebago Dakota Sioux who played catcher for the Kansas City Monarchs of Negro league baseball. They lived in north Minneapolis, in a poor neighborhood near 6th and Lyndale Avenues North called the Hellhole, known for prostitution, drinking, and gambling. Later the area was covered by the junction of Olson Memorial Highway and Interstate 94.[1]

Davis was paralyzed from the waist down by polio at the age of two or three until about the age of five. His mother had learned a polio treatment from an ancestor who was a doctor on a plantation in Virginia. She helped to free Davis from his illness through massage and warm water wraps, applying an iron to keep the wraps warm. Davis was the first African-American student at Michael Dowling School for Crippled Children. He was not allowed treatment at Shriners Hospital, but he received a great deal of help at the school from a visiting doctor from City Hospital. Later Elizabeth Kenny, an Australian nurse who joined the City Hospital staff in 1940, would found the Sister Kenny Rehabilitation Institute in Minneapolis and provide treatment and physical therapy similar to that used by Davis's mother.[2][3]

While growing up Davis was known as Little Pops. His second home was the Phyllis Wheatley settlement house. Its director Gertrude Brown gave the area's children continuing education in a safe place to go after school. Davis must have gotten into trouble at some point as it was a juvenile parole officer who suggested he attend Phyllis Wheatley. There with his friends, Davis learned boxing, etiquette, and Robert's Rules of Order. They met Chick Webb and danced to Duke Ellington and Count Basie who stayed there on tours to the Orpheum Theatre. In 1941, he graduated from North High School where he lettered in and won a city championship in boxing. Davis attended the University of Minnesota and later in life received an honorary doctorate in law from Macalester College.

Davis and his wife, Charlotte, a community leader, were married for 61 years. They had four children, Rita Lyell, Harry Jr., Richard, and Evan.[4][5][6][7][8]

Golden Gloves boxing

Phyllis Wheatley taught amateur boxing as exercise and a fun sport, as well as to discourage street fighting, and as a form of self-defense. Davis founded the center's competitive boxing program during the 1940s, coached basketball, football, and baseball, and served on the center's board of directors for thirty years. Between 1945 and 1960, Phyllis Wheatley won most of the boxing championships for the upper Midwest region that included Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wisconsin.

Davis became the region's most successful coach and vice president of Golden Gloves. Davis taught "don't misuse it or abuse it," and three principles of body, mind, and conscience. Among his students were Clyde Bellecourt who cofounded the American Indian Movement and Jimmy Jackson who won a national Golden Gloves championship in 1957.[9][10][11] He established a strong relationship to the other winners from Minneapolis, including Duane Bobick, Jack Graves, Virgil Hill, Roland Miller, Pat O'Connor, Don Sargeant, and Dave Sherbrooke. Davis was inducted into the Golden Gloves Hall of Fame.[5][6][12]

Civic leadership

In 1945 he became a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), an organization he influenced throughout his life. In 1957 Davis and other lay leaders worked with pastors Chester Pennington and C. M. Sexton on the merger of Border Methodist with Hennepin Avenue Methodist. The predominantly white downtown congregation now known as Hennepin Avenue United Methodist Church invited the Border congregation when they lost their church to urban redevelopment.[13] In 1966 Davis and group of eight others founded the Twin Cities Opportunity Industrialization Center (TCOIC), a program both criticized for excessive spending and lauded for providing job training to local African Americans.

In 1967, after large-scale disturbances in several major U.S. cities, the largely African-American neighborhood around Plymouth Avenue in north Minneapolis witnessed urban unrest. After several buildings were set on fire, Davis worked with mayor Arthur Naftalin to resolve tensions between community members and the police.[14] During this time Davis worked locally on the War on Poverty and founded the Urban Coalition of Minneapolis.

Davis served for twenty years on the Minneapolis school board, as chair beginning in 1974. A judge ordered Minneapolis to address concentrations of races in parts of the city and their schools. To reach enrollment goals counted by race, school closings, school busing, redistricting and other plans were tried beginning in 1972.[15] Davis continued to be active in school issues as late as 2006, when he supported Thandiwe Peebles, who resigned as superintendent.[16]

Mayoral run

The city of Minneapolis was comparatively progressive but racial segregation was the norm in the United States. The country saw racial violence and clashes with police sometimes called militant following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968. Part of an effort to build peace, Davis agreed to run for mayor in 1971 against the incumbent and independent Charles Stenvig, former head of the Minneapolis police federation, whom Davis later called his friend. Soon endorsed by the Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party, Davis ran as the city's first African-American mayoral candidate supported by a major political party.

When integration or desegregation began in the 1960s, black families sometimes experienced frightening persecution in Minneapolis by individuals and groups behaving like the latter-day Ku Klux Klan in southern cities. These forces were still present in the city in 1971. The Davis family received daily threats to their safety during the campaign. The FBI brought them guard dogs and the police department had to station guards at their home. White politicians, Donald M. Fraser, Hubert Humphrey and Walter Mondale sometimes accompanied Davis. As expected, Stenvig won reelection. Davis won the admiration of many.[6][12]

Harry was willing to be a human bridge between black and white when this city really needed one. I shudder to think what might have happened if that bridge had not been there.

Dr. King did a lot for African-Americans in Minnesota, but Minnesotans also did a lot for Martin Luther King.

Among large cities in the United States who had African-American mayors about this time, Cleveland elected Carl Stokes in 1967, and Newark, New Jersey, elected Kenneth Gibson in 1970. In 1973, Thomas Bradley and Maynard H. Jackson won in Los Angeles and Atlanta. Minneapolis did not elect a black mayor for twenty more years. Sharon Sayles Belton, who saw Davis's concession speech in 1971, assumed office in 1994 and served through 2001.

Star Tribune

Throughout his career, Davis was known to the Minneapolis newspapers who covered Golden Gloves regularly and it was in the news publishing industry that he became the city's first prominent black business executive who large numbers of the white population recognized. Earlier Davis was a production foreman and later employee services manager for Onan Corporation and the founding chief executive of the Urban Coalition. He started at what is now the Star Tribune newspaper in 1973. Davis became assistant vice president in public affairs and assistant vice president in employee services. When he retired in 1987 he was vice president of the paper's parent company, Cowles Media.[5] The Star Tribune became part of McClatchy who sold it to Avista in 2006.

Olympic boxing

Davis served on the United States Olympic boxing committee during the 1970s and 1980s for Golden Gloves whose champions were eligible for Olympic competition. He was manager, responsible for the team's wellbeing, including lodging and logistics and medical care, for the second place trial team at the Summer Olympics in Montreal in 1976.[2] In 1980 the United States led a boycott of the Summer Olympics in Moscow, where Cuba dominated men's boxing.

In 1984 in Los Angeles, Cuba was among the group of countries who boycotted with the Soviet Union. Under coach Pat Nappi,[19] Davis was again team manager for the United States.[2] Individual wins were contested and Evander Holyfield was disqualified. Paul Gonzales, Steve McCrory, Meldrick Taylor, Pernell Whitaker, Jerry Page, Mark Breland, Frank Tate, Henry Tillman and Tyrell Biggs won gold medals and Virgil Hill won silver.[20] Except when the United States competed alone in St. Louis in 1904 and won every medal, the 1984 team's nine gold and one silver is the best record in a single Olympic boxing tournament. Cuba returned in 1992 in the Barcelona games to win seven gold and one silver with no boycotts.

Later years

Davis received at least seventy nine civic leadership awards.[5] In 2002, West Central Academy, a Minneapolis middle school, was renamed W. Harry Davis Academy.[21] A foundation, award and scholarship also carry his name. Davis published his autobiography Overcoming in 2002. In 2003, he published Changemaker, a history of the civil rights movement in Minnesota for young readers aged 10 and up, based on his memoirs. Lori Sturdevant of the Star Tribune edited both books, which were published by the historical society of Afton, Minnesota.

Davis recovered from lymphoma during the 1980s. A recurrence of the disease took his life about three years after his wife's death.

Bibliography

- Davis, W. Harry; Sturdevant, Lori (2002). Overcoming: The Autobiography of W. Harry Davis. Afton Historical Society Press. ISBN 1-890434-52-3.

- Davis, W. Harry; Sturdevant, Lori (2003). Changemaker. Afton Historical Society Press. ISBN 1-890434-60-4.

Notes

- W. Harry Davis (August 2003). "Changemaker excerpt, Afton Historical Society Press". Archived from the original on December 7, 2006. Retrieved January 24, 2007.

- W. Harry Davis (September 2002). Overcoming: The Autobiography of W. Harry Davis. Afton Historical Society Press, Lori Sturdevant (ed.). ISBN 1-890434-52-3.

- Minneapolis Public Library (2001). "History of Minneapolis: Medicine". Archived from the original on November 22, 2007. Retrieved January 24, 2007.

- Benson, Lorna (August 11, 2006). "Harry Davis -- a life of accomplishment". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved January 20, 2007.

- Phyllis Wheatley Community Center (2006). "W. Harry Davis, Sr". Archived from the original on July 30, 2007. Retrieved January 20, 2007.

- Petey (August 14, 2006). "The Cyber Boxing Zone Message Board". Retrieved January 20, 2007.

- Rotary Club of Saint Paul (January 24, 2006). "Rotary in Review, in The Hub (PDF)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2007. Retrieved January 20, 2007.

- Hahn, Trudi (November 4, 2003). "Charlotte Davis dies at 77; was leader in black community". Minneapolis Star Tribune. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved January 20, 2007.

- Levy, Paul (n.d.). "Clyde Bellecourt: Thunder fills his works and words". Minneapolis Star Tribune. Retrieved January 20, 2007.

- Reusse, Patrick (August 19, 2006). "It was great to have Davis in your corner". Minneapolis Star Tribune. Archived from the original on August 21, 2006. Retrieved January 22, 2007.

- Golden Gloves of America (n.d.). "History". Retrieved January 22, 2007.

- Twin Cities Public Television (February 21, 2003). "Harry Davis on Almanac (RealVideo)". Archived from the original on June 26, 2006. Retrieved January 20, 2007.

- Hennepin Avenue United Methodist Church (January 8, 2007). "Celebrating 50 Years with Border Church". Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved January 23, 2007.

- Rotary Club of Minneapolis (March 28, 2003). "Club Nine News Volume LXXXVII Number 37 (PDF)" (PDF). Retrieved January 20, 2007.

- MPS Communications Department (April 8, 2004). "History of Desegregation in MPS, in An Overview of Minneapolis Public Schools (PDF)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 12, 2007. Retrieved January 24, 2007.

- Robson, Britt & Beth Hawkins (February 8, 2006). "We're All Bozos on This Board". City Pages, Volume 27 - Issue 1314. Retrieved January 24, 2007.

- Minneapolis South Rotary Club (2007). "welcome page". Retrieved January 22, 2007.

- Kahn, Aron (August 12, 2006). "W. Harry Davis, 83, civil rights pioneer". Pioneer Press. Retrieved January 22, 2007.

- The New York Times (March 1, 1993). "Pat Nappi Olympic Coach, 75". Retrieved January 22, 2007.

- Official Report of the Games of the XXIIIrd Olympiad Los Angeles, 1984 (1985). "Volume 2 Competition Summary and Results, via Amateur Athletic Foundation of Los Angeles" (PDF). Los Angeles Olympic Organizing Committee. Retrieved January 22, 2007.

- Smith, Cheyenne, Cierra Muse and Zaurean Mekens (September 22, 2003). "W. Harry Davis Academy: KBEM School News". Retrieved January 20, 2007.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

References

- Benson, Lorna (August 11, 2006). "Harry Davis -- a life of accomplishment". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved January 20, 2007.

- Phyllis Wheatley Community Center (2006). "W. Harry Davis, Sr". Archived from the original on July 30, 2007. Retrieved January 20, 2007.

- Interview, African American Registry (April 12, 2002). "One of Minnesota's finest, Harry Davis Sr". Archived from the original on October 27, 2006. Retrieved January 20, 2007.

- Rotary Club of Saint Paul (January 24, 2006). "Rotary in Review, in The Hub (PDF)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2007. Retrieved January 20, 2007.

- Twin Cities Public Television (February 21, 2003). "Harry Davis on Almanac (RealVideo)". Archived from the original on June 26, 2006. Retrieved January 20, 2007.

External links

- Harry Davis Sr. at the African American Registry

- W. Harry Davis Academy

- Phyllis Wheatley Community Center