Wakame

Wakame (ワカメ), Undaria pinnatifida, is a species of edible seaweed, a type of marine algae, and a sea vegetable. It has a subtly sweet, but distinctive and strong flavour and texture. It is most often served in soups and salads.

| Wakame | |

|---|---|

| |

| mature sporophyte | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Clade: | SAR |

| Phylum: | Ochrophyta |

| Class: | Phaeophyceae |

| Order: | Laminariales |

| Family: | Alariaceae |

| Genus: | Undaria |

| Species: | U. pinnatifida |

| Binomial name | |

| Undaria pinnatifida (Harvey) Suringar, 1873 | |

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 188 kJ (45 kcal) |

9.14 g | |

| Sugars | 0.65 g |

| Dietary fiber | 0.5 g |

0.64 g | |

3.03 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Thiamine (B1) | 5% 0.06 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 19% 0.23 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 11% 1.6 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 14% 0.697 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 49% 196 μg |

| Vitamin C | 4% 3 mg |

| Vitamin E | 7% 1 mg |

| Vitamin K | 5% 5.3 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 15% 150 mg |

| Iron | 17% 2.18 mg |

| Magnesium | 30% 107 mg |

| Manganese | 67% 1.4 mg |

| Phosphorus | 11% 80 mg |

| Sodium | 58% 872 mg |

| Zinc | 4% 0.38 mg |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA FoodData Central | |

Sea farmers in Japan have grown wakame since the Nara period.[1] As of 2018, the Invasive Species Specialist Group has listed the species on its list of 100 worst globally invasive species.[2]

Etymology

In Old Japanese, me stood for edible seaweeds in general as opposed to mo standing for algae. In kanji, such as 海藻, 軍布 and 和布 were applied to transcribe the word.[7] Among seaweeds, wakame was likely most often eaten, therefore me especially meant wakame.[8] It expanded later to other seaweeds like kajime, hirome (kombu), arame, etc. Wakame is derived from waka + me (若布, lit. young seaweed). If this waka is a eulogistic prefix, same as the tama of tamagushi, wakame likely stood for seaweeds widely in ancient ages.[7] In Man'yōshū, in addition to 和可米 and 稚海藻 (both are read as wakame), nigime (和海藻, soft wakame) can be seen. Besides, tamamo (玉藻, lit. beautiful algae), which often appeared in Man'yo-shu, may be wakame depending on poems.

History in the West

The earliest appearance in Western documents is probably in Nippo Jisho (1603), as Vacame.[7]

In 1867 the word "wakame" appeared in an English-language publication, A Japanese and English Dictionary, by James C. Hepburn.[9]

Starting in the 1960s, the word "wakame" started to be used widely in the United States, and the product (imported in dried form from Japan) became widely available at natural food stores and Asian-American grocery stores, due to the influence of the macrobiotic movement, and in the 1970s with the growing number of Japanese restaurants and sushi bars.

Health

Studies conducted at Hokkaido University have found that a compound in wakame known as fucoxanthin can help burn fatty tissue.[10] Studies in mice have shown that fucoxanthin induces expression of the fat-burning protein UCP1 that accumulates in fat tissue around the internal organs. Expression of UCP1 protein was significantly increased in mice fed fucoxanthin. Wakame is also used in topical beauty treatments. See also Fucoidan.

Wakame is a rich source of eicosapentaenoic acid, an omega-3 fatty acid. At over 400 mg/(100 kcal) or almost 1 mg/kJ, it has one of the higher nutrient-to-energy ratios for this nutrient, and among the very highest for a vegetarian source.[11] A typical 10–20 g (1–2 tablespoon) serving of wakame contains roughly 16 to 31 kJ (3.75 to 7.5 kcal) and provides 15–30 mg of omega-3 fatty acids. Wakame also has high levels of sodium, calcium, iodine, thiamine and niacin.

In Oriental medicine it has been used for blood purification, intestinal strength, skin, hair, reproductive organs and menstrual regularity.[12]

In Korea, the soup miyeokguk is popularly consumed by women after giving birth as sea mustard (miyeok) contains a high content of calcium and iodine, nutrients that are important for nursing new mothers. Many women consume it during the pregnancy phase as well. It is also traditionally eaten on birthdays for this reason, a reminder of the first food that the mother has eaten and passed on to her newborn through her milk.

Aquaculture

Japanese and Korean sea-farmers have grown wakame for centuries, and are still both the leading producers and consumers.[13] Wakame has also been cultivated in France since 1983, in sea fields established near the shores of Brittany.[14]

Wild grown wakame is harvested in Tasmania, Australia, and then sold in restaurants in Sydney[15] and also sustainably hand-harvested from the waters of Foveaux Strait in Southland, New Zealand and freeze-dried for retail and use in a range of products.[16]

Cuisine

Wakame fronds are green and have a subtly sweet flavour and satiny texture. The leaves should be cut into small pieces as they will expand during cooking.

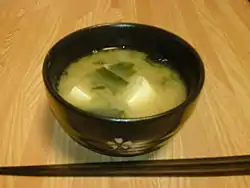

In Japan and Europe, wakame is distributed either dried or salted, and used in soups (particularly miso soup), and salads (tofu salad), or often simply as a side dish to tofu and a salad vegetable like cucumber. These dishes are typically dressed with soy sauce and vinegar/rice vinegar.

Goma wakame, also known as seaweed salad, is a popular side dish at American and European sushi restaurants. Literally translated, it means "sesame seaweed", as sesame seeds are usually included in the recipe.

Miyeok guk, a Korean soup made with miyeok

Miyeok guk, a Korean soup made with miyeok A Japanese dish consisting of wakame with sardines

A Japanese dish consisting of wakame with sardines

Invasive species

Native to cold temperate coastal areas of Japan, Korea, and China, in recent decades it has become established in temperate regions around the world, including New Zealand, the United States, Belgium,[17] France, Great Britain, Spain, Italy, Argentina, Australia and Mexico.[18][19] It was nominated one of the 100 worst invasive species in the world.[2] Undaria is commonly initially introduced or recorded on artificial structures, where its r-selected growth strategy facilitates proliferation and spread to natural reef sites. Undaria populations make a significant but inconsistent contribution of food and habitat to intertidal and subtidal reefs. Undaria invasion can cause changes to native community composition at all trophic levels. As well as increasing primary productivity, it can reduce the abundance and diversity of understory algal assemblages, out-compete some native macroalgal species and affect the abundance and composition of associated epibionts and macrofauna: including gastropods, crabs, urchins and fish.[20]

New Zealand

In New Zealand, Undaria pinnatifida was declared as an unwanted organism in 2000 under the Biosecurity Act 1993. It was first discovered in Wellington Harbour in 1987 and probably arrived as hull fouling on shipping or fishing vessels from Asia.[21][22]

Wakame is now found around much of New Zealand, from Stewart Island to as far north as the subtropical waters of Karikari Peninsula.[23] It spreads in two ways: naturally, through the millions of microscopic spores released by each fertile organism, and through human mediated spread, most commonly via hull fouling and with marine farming equipment.[24] It is a highly successful and fertile species, which makes it a serious invader. However, its impacts are not well understood and vary depending on the location.

Even though it is an invasive species, in 2012 the government allowed for the farming of wakame in Wellington, Marlborough and Banks Peninsula.[25]

United States

The seaweed has been found in several harbors in southern California. In May 2009 it was discovered in San Francisco Bay and aggressive efforts are underway to remove it before it spreads.[26][27][28]

See also

References

- Man'yōshū "比多潟の 磯のわかめの 立ち乱え 我をか待つなも 昨夜も今夜も" (Poetry on the theme of Wakame). Mouritsen, Ole G.; Rhatigan, Prannie; Pérez-Lloréns, José Lucas (2018). World cuisine of seaweeds: Science meets gastronomy. International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science. 14. p. 57. doi:10.1016/j.ijgfs.2018.09.002.

- "Global Invasive Species Database". IUCN Species Survival Commission. Retrieved 2009-08-17.

- "Undaria pinnatifida". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- "Undaria pinnatifida". Seaweed Industry Association.

- Kwon, Mya (June 5, 2013). "Sea Mustard aka "Miyeok"(Korean) or "Wakame"(Japanese)" (PDF). Washington.edu. Retrieved February 9, 2020.

- Abbott, Isabella A (1989). Lembi, Carole A.; Waaland, J. Robert (eds.). Algae and human affairs. Cambridge University Press, Phycological Society of America. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-521-32115-0.

- 小学館国語辞典編集部 (ed.) (2006), 『日本国語大辞典』 精選版 (Nihon Kokugo Daijiten, Shorter Edition), 小学館

- There is also a theory : initially me stood for only wakame, and expanded to the word for general seaweeds afterwards. See 小島憲之 et al. (ed. & tr.) (1995), 『新編 日本古典文学全集7 萬葉集(2)』, 小学館, p.225

- Hepburn, James Curtis (1867). A Japanese and English dictionary: with and English and Japanese index. American Presbyterian Mission Press. p. 516.

WAKAME, ワカメ, 若海布, n, A kind of sea weed.

- Maeda, H.; Hosokawa, M.; Sashima, T.; Funayama, K.; Miyashita, K. (2005). "Fucoxanthin from edible seaweed, Undaria pinnatifida, shows antiobesity effect through UCP1 expression in white adipose tissues". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 332 (2): 392–397. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.002. PMID 15896707.

- "545 foods highest in 20:5 n-3". Nutrition Data. Retrieved 2007-02-09.

- Kristina Turner (1996). The Self-Healing Cookbook: A Macrobiotic Primer for Healing Body, Minds and Moods with Whole Natural Foods. ISBN 978-0-945668-10-7.

- "1. THE SEAWEED INDUSTRY - AN OVERVIEW".

- http://www.jncc.gov.uk/page-1676 Archived 2010-10-13 at the Wayback Machine Undaria pinnatifida

- "Greens straight out of the blue". The Sydney Morning Herald. August 11, 2009.

- "Pest seaweed could be used against cancer". Southland Times. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- Hillewaert, Hans. "Wakame - Undaria pinnatifida". Waarnemingen.be. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- Torres, A. R. I.; Gil, M. N. N.; Esteves, J. L. (2004). "Nutrient uptake rates by the alien alga Undaria pinnatifida (Phaeophyta) (Nuevo Gulf, Patagonia, Argentina) when exposed to diluted sewage effluent". Hydrobiologia. 520 (1–3): 1–6. doi:10.1023/B:HYDR.0000027686.63170.6c. S2CID 36999841.

- James, K; Kibele, J; Shears, N. T. (2015). "Using satellite-derived sea surface temperature to predict the potential global range and phenology of the invasive kelp Undaria pinnatifida". Biological Invasions. 17 (12): 3393–3408. doi:10.1007/s10530-015-0965-5. S2CID 13515136.

- James K. (2016) A review of the impacts from invasion by the introduced kelp Undaria pinnatifida. Report: TR 2016/40: Waikato Regional Council. https://www.waikatoregion.govt.nz/services/publications/technical-reports/2016/tr201640/

- Hay, Cameron H.; Luckens, Penelope A. (1987-01-01). "The Asian kelp Undaria pinnatifida (Phaeophyta: Laminariales) found in a New Zealand harbour". New Zealand Journal of Botany. 25 (2): 329–332. doi:10.1080/0028825X.1987.10410079.

- Nelson, W. A. (2013). New Zealand seaweeds : an illustrated guide. Wellington, New Zealand: Te Papa Press. p. 94. ISBN 9780987668813. OCLC 841897290.

- James K, Middleton I, Middleton C, Shears NT (2014) Discovery of Undaria pinnatifida (Harvey) Suringar, 1873 in northern New Zealand indicates increased invasion threat in subtropical regions. BioInvasions Rec 3(1):21-24 http://www.reabic.net/journals/bir/2014/Issue1.aspx

- James K, Shears NT (2016) Proliferation of the invasive kelp Undaria pinnatifida at aquaculture sites promotes spread to coastal reefs. Marine Biology 163(2):1-12

- "Areas designated for Undaria farming". Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries. 19 January 2012. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- Kay, J. Kelp among top 10 invasive seaweeds hits S.F. San Francisco Chronicle July 8, 2009.

- Perlman, D. Divers battle fast-growing alien kelp in bay San Francisco Chronicle July 9, 2009.

- "An Underwater Fight Is Waged for the Health of San Francisco Bay" article by Malia Wollan in The New York Times August 1, 2009

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Undaria pinnatifida as food. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Undaria pinnatifida. |

- Wakame Seaweed at About.com

- AlgaeBase link

- Undaria pinnatifida at the FAO

- Undaria pinnatifida at the Joint Nature Conservation Committee, UK

- Global Invasive species database

- Undaria Management at the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary