Walt Whitman's lectures on Abraham Lincoln

Walt Whitman gave a series of lectures on Abraham Lincoln from 1879 to 1890. They centered around the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, but also covered years leading up to and during the American Civil War and sometimes included readings of poems such as "O Captain! My Captain!". The lectures began as a benefit for Whitman and were generally popular and well received.

Deliveries

Whitman had long aspired to be a lecturer, and had given several in the 1850s and 1860s.[1] In 1875 Whitman had published Memoranda During the War, which included a narrative of Lincoln's death.[2] The following year he published an article on Lincoln's death in The New York Sun[3] and he considered writing a book on Lincoln, but never did.[4] The idea of Whitman giving lectures on Lincoln's death was first suggested by his friend John Burroughs in a letter dated February 3, 1878, who told him that Richard Watson Gilder wanted him to deliver a lecture on the anniversary of Lincoln's assassination. Nothing happened in 1878 as Whitman was in poor health.[5][6][7] The following year a group, including Gilder, set up a lecture on Lincoln's death to be given by Whitman.[4] Whitman worked his New York Sun article into a readable format and was given a chair so that he could sit throughout the lecture.[5]

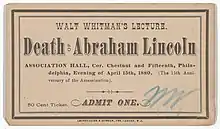

The first lecture was given in Steck Hall, New York City, to between 60 and 80 people on April 14, 1879.[8][9] Whitman initially struggled to find further bookings for lectures and did not give another lecture until April 15, 1880, in Association Hall, Philadelphia. He revised it slightly for the second reading; it would stay in largely the same form for the remainder of his lectures.[10] Whitman promoted the lecture heavily, sending copies to several newspapers. An 1881 lecture in Boston was attended by over one hundred people, including William Dean Howells, and earned him $135.[11] He had delivered it at least six times by May 1886.[12]

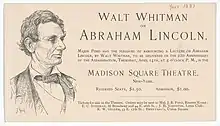

Whitman said that he gave the lecture a total of thirteen times,[12] but later authors give varying numbers—estimates range from five[13] to twenty.[lower-alpha 1][2] Whitman's April 15, 1887 lecture at Madison Square Theatre is considered the most successful of the lectures.[16] David S. Reynolds wrote in 1995 that the lecture was a "Barnumesque event on a high scale."[17] It was organized by Robert Pearsall Smith and several other friends of Whitman.[18] Attendees included James Russell Lowell, Frances Hodgson Burnett, Andrew Carnegie, Edmund Clarence Stedman, Wilson Barrett, Mark Twain, Frank Stockton, Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer, William T. Sherman and John Hay.[19][20] At the end of the lecture, Stedman's granddaughter brought Whitman lilacs and he read the "O Captain! My Captain!". A reception at Whitman's hotel suite was held after the lecture; several hundred people attended.[21] Whitman later described the lecture and its aftermath as "the culminating hour" of his life;[22] he earned $600 from the event, of which $350 was from Carnegie.[23] However, he also told his friend Horace Traubel that he considered the event "too much the New York Jamboree".[23] The last time he gave the lecture was on April 14, 1890 in Philadelphia, just two years before his death.[4][24] Money made from lectures constituted a major source of income for Whitman in the years leading to his death.[25]

Content and reception

Whitman was described as not being an orator "either in manner or appearance". He spoke in a low voice[4] and generally began by "downplaying his ability to handle the emotionally challenging task that lay before him."[26] He then moved into describing the rise in tensions leading up to the 1860 presidential election[27] and America during the Civil War era. Next he would describe Lincoln's death, which was the lecture's "main event". He retold the assassination as though he was there, identifying the assassination as a force that would "condense—A nationality."[lower-alpha 2][26] He often ended by reading "O Captain! My Captain!",[4] but also occasionally read other poems from Leaves of Grass and even works of other poets such as "The Raven" by Edgar Allan Poe, poems by William Collins, and a translation of Anacreon's Ode XXXIII by Thomas Moore called "The Midnight Visitor."[13]

The lectures were popular and well received.[4] Historian Daniel Mark Epstein wrote that "the speech was always a success, and in major cities it seldom failed to reap columns of publicity in the newspapers."[29] Many audience members reported being moved to tears.[24] José Martí, who was also present at one of the lectures, described the crowd as listening "in religious silence, for its sudden grace notes, vibrant tones, hymnlike progress, and Olympian familiarity seemed at times the whispering of the stars." Stedman wrote that "Something of Lincoln himself seemed to pass into this man who loved and studied him."[30] The poet Stuart Merrill said that Whitman's telling of the assassination convinced him that “I was there, the very thing happened to me. And this recital was as gripping as the messengers' reports in Aeschylus."[31]

Whitman's biographer Justin Kaplan wrote in 1980 that Whitman's 1887 lecture in New York City and its after-party marked the closest he came to "social eminence on a large scale."[22] Eight years later the professor Kerry C. Larson wrote that the "hackneyed" sentimentality of Whitman's lectures indicated a decline in his creativity.[32] In 2015 the scholar Michael C. Cohen called Whitman's lecture his "most popular text". Cohen argued that Whitman had used the lectures to frame the Civil War and Lincoln's death as factors that could unify the United States.[33]

See also

Notes

- Barton wrote in 1965 that he considered thirteen to be "too large" and was able to compile a list of nine definite occasions.[14] Loving argued in 1999 that ten was "the best estimate".[15]

- While Whitman had not seen Lincoln's assassination, he interviewed his friend Peter Doyle and based his lectures in part on Doyle's account.[28]

References

- Barton 1965, pp. 187–188.

- Cushman 2014, p. 47.

- Barton 1965, p. 191.

- Peterson 1995, pp. 138–139.

- Barton 1965, pp. 192–193.

- Glicksberg 1933, p. 173.

- Loving 1999, p. 386.

- Barton 1965, p. 194.

- Reynolds 1995, p. 531.

- Barton 1965, pp. 195–197.

- Reynolds 1995, p. 534.

- Azarnoff, Roy S. (September 1, 1963). "Walt Whitman's Lecture on Lincoln in Haddonfield". Walt Whitman Review. IX: 65–66.

- Golden, Arthur (October 1, 1988). "The Text of a Whitman Lincoln Lecture Reading: Anacreon's "The Midnight Visitor"". Walt Whitman Quarterly Review. 6 (2): 91–94. doi:10.13008/2153-3695.1208. ISSN 0737-0679.

- Barton 1965, pp. 194; 214.

- Loving 1999, p. 440.

- Barton 1965, p. 209.

- Reynolds 1995, p. 554.

- Epstein 2004, p. 319.

- "Walt Whitman Lectures on Abraham Lincoln". The Washington Post. April 15, 1887.

- Epstein 2004, pp. 325–327.

- Kaplan 1980, p. 30.

- Kaplan 1980, p. 31.

- Reynolds 1995, p. 555.

- Griffin, Larry D. "Death of Abraham Lincoln (1879)". The Walt Whitman Archive. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- Reynolds 1995, p. 524.

- Levin & Whitley 2018, pp. 102–103.

- Reynolds 1995, p. 441.

- Eiselein, Gregory. "Lincoln's Death". The Walt Whitman Archive. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- Epstein 2004, p. 323.

- Peterson 1995, pp. 139–140.

- Levin & Whitley 2018, p. 102.

- Larson 1988, p. 232.

- Cohen 2015, p. 157.

Bibliography

- Barton, William E (1965). Abraham Lincoln and Walt Whitman. Port Washington, New York: Kennikat Press. ISBN 9780804600187. OCLC 1145780794.

- Cohen, Michael C. (2015). The Social Lives of Poems in Nineteenth-Century America. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-4708-4.

- Cushman, Stephen (2014). Belligerent Muse: Five Northern Writers and How They Shaped Our Understanding of the Civil War. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-4696-1877-7. OCLC 875742493.

- Epstein, Daniel Mark (2004). Lincoln and Whitman: Parallel Lives in Civil War Washington (1st ed.). New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-45799-4. OCLC 52980509.

- Glicksberg, Charles I., ed. (1933). Walt Whitman and the Civil War: A Collection of Original Articles and Manuscripts. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-1-5128-0167-5. JSTOR j.ctv51338s.

- Kaplan, Justin (1980). Walt Whitman, a Life. New York City: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-671-22542-1. OCLC 6305249.

- Larson, Kerry C. (November 21, 1988). Whitman's Drama of Consensus. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-46908-9.

- Levin, Joanna; Whitley, Edward (May 31, 2018). Walt Whitman in Context. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-31447-3.

- Loving, Jerome (1999). Walt Whitman: The Song of Himself. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21427-7. OCLC 39313629.

- Peterson, Merrill D. (June 1, 1995). Lincoln in American Memory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-802304-3.

- Reynolds, David S. (1995). Walt Whitman's America: A Cultural Biography (1st ed.). New York City: Knopf. ISBN 0-394-58023-0. OCLC 30547827.