Wardriving

Wardriving is the act of searching for Wi-Fi wireless networks, usually from a moving vehicle, using a laptop or smartphone. Software for wardriving is freely available on the internet.

Warbiking, warcycling, warwalking and similar use the same approach but with other modes of transportation.

Etymology

War driving originated from wardialing, a method popularized by a character played by Matthew Broderick in the film WarGames, and named after that film. War dialing consists of dialing every phone number in a specific sequence in search of modems.[1]

Variants

Warbiking or warcycling is similar to wardriving, but is done from a moving bicycle or motorcycle. This practice is sometimes facilitated by mounting a Wi-Fi enabled device on the vehicle.

Warwalking, or warjogging, is similar to wardriving, but is done on foot rather than from a moving vehicle. The disadvantages of this method are slower speed of travel (but leading to discovery of more infrequently discovered networks) and the absence of a convenient computing environment. Consequently, handheld devices such as pocket computers, which can perform such tasks while users are walking or standing, have dominated this practice. Technology advances and developments in the early 2000s expanded the extent of this practice. Advances include computers with integrated Wi-Fi, rather than CompactFlash (CF) or PC Card (PCMCIA) add-in cards in computers such as Dell Axim, Compaq iPAQ and Toshiba pocket computers starting in 2002. More recently, the active Nintendo DS and Sony PSP enthusiast communities gained Wi-Fi abilities on these devices. Further, many newer smartphones integrate Wi-Fi and Global Positioning System (GPS).

Warrailing, or Wartraining, is similar to wardriving, but is done on a train or tram rather than from a slower more controllable vehicle. The disadvantages of this method are higher speed of travel (resulting in less discovery of more infrequently discovered networks) and often limited to major roads with a higher traffic.

Warkitting is a combination of wardriving and rootkitting.[2] In a warkitting attack, a hacker replaces the firmware of an attacked router. This allows them to control all traffic for the victim, and could even permit them to disable TLS by replacing HTML content as it is being downloaded.[3] Warkitting was identified by Tsow, Jakobsson, Yang, and Wetzel.

Mapping

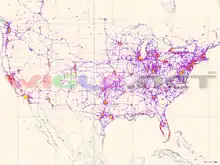

Wardrivers use a Wi-Fi-equipped device together with a GPS device to record the location of wireless networks. The results can then be uploaded to websites like WiGLE, openBmap or Geomena where the data is processed to form maps of the network neighborhood. There are also clients available for smartphones running Android that can upload data directly. For better range and sensitivity, antennas are built or bought, and vary from omnidirectional to highly directional.

The maps of known network IDs can then be used as a geolocation system—an alternative to GPS—by triangulating the current position from the signal strengths of known network IDs. Examples include Place Lab by Intel, Skyhook, Navizon[4] by Cyril Houri, SeekerLocate from Seeker Wireless, openBmap and Geomena. Navizon and openBmap combines information from Wi-Fi and cell phone tower maps contributed by users from Wi-Fi-equipped cell phones.[5][6] In addition to location finding, this provides navigation information, and allows for the tracking of the position of friends, and geotagging.

In December 2004, a class of 100 undergraduates worked to map the city of Seattle, Washington over several weeks. They found 5,225 access points; 44% were secured with WEP encryption, 52% were open, and 3% were pay-for-access. They noticed trends in the frequency and security of the networks depending on location. Many of the open networks were clearly intended to be used by the general public, with network names like "Open to share, no porn please" or "Free access, be nice." The information was collected into high-resolution maps, which were published online.[7][8] Previous efforts had mapped cities such as Dublin.[9]

Legal and ethical considerations

Some portray wardriving as a questionable practice (typically from its association with piggybacking), though, from a technical viewpoint, everything is working as designed: many access points broadcast identifying data accessible to anyone with a suitable receiver. It could be compared to making a map of a neighborhood's house numbers and mail box labels.[10]

While some may claim that wardriving is illegal, there are no laws that specifically prohibit or allow wardriving, though many localities have laws forbidding unauthorized access of computer networks and protecting personal privacy. Google created a privacy storm in some countries after it eventually admitted systematically but surreptitiously gathering Wi-Fi data while capturing video footage and mapping data for its Street View service.[11] It has since been using Android-based mobile devices to gather this data.[12]

Passive, listen-only wardriving (with programs like Kismet or KisMAC) does not communicate at all with the networks, merely logging broadcast addresses. This can be likened to listening to a radio station that happens to be broadcasting in the area or with other forms of DXing.

With other types of software, such as NetStumbler, the wardriver actively sends probe messages, and the access point responds per design. The legality of active wardriving is less certain, since the wardriver temporarily becomes "associated" with the network, even though no data is transferred. Most access points, when using default "out of the box" security settings, are intended to provide wireless access to all who request it. The war driver's liability may be reduced by setting the computer to a static IP, instead of using DHCP, preventing the network from granting the computer an IP address or logging the connection.[13]

In the United States, the case that is usually referenced in determining whether a network has been "accessed" is State v. Allen. In this case, Allen had been wardialing in an attempt to get free long-distance calling through Southwestern Bell's computer systems. When presented with a password protection screen, however, he did not attempt to bypass it. The court ruled that although he had "contacted" or "approached" the computer system, this did not constitute "access" of the company's network.[14][15][16][17][18]

Software

- iStumbler

- InSSIDer

- Kismet

- KisMAC

- NetSpot[19]

- NetStumbler

- WiFi-Where[20]

- WiGLE for Android

There are also homebrew wardriving applications for handheld game consoles that support Wi-Fi, such as sniff jazzbox/wardive for the Nintendo DS/Android, Road Dog for the Sony PSP, WiFi-Where for the iPhone, G-MoN, Wardrive,[21] Wigle Wifi for Android, and WlanPollution[22] for Symbian NokiaS60 devices. There also exists a mode within Metal Gear Solid: Portable Ops for the Sony PSP (wherein the player is able to find new comrades by searching for wireless access points) which can be used to wardrive. Treasure World for the DS is a commercial game in which gameplay wholly revolves around wardriving.

References

- "War Driving Attack".

- Tsow, Alex. "Warkitting: the Drive-by Subversion of Wireless Home Routers" (PDF).

- Myers, Steven. "Practice and Prevention of Home-Router Mid-Stream Injection Attacks".

- "WiFi and Cell-ID location database with Global coverage".

- Rose, Frank (June 2006). "Lost and Found in Manhattan". Wired (14.06). Retrieved 1 September 2007.

- Blackwell, Gerry (19 December 2005). "Using Wi-Fi/Cellular in P2P Positioning". Wi-Fi Planet. Retrieved 1 September 2007.

- Marwick, Alice (15 February 2005). "Seattle WiFi Map Project". Students of COM300, Fall 2004 – Basic Concepts of New Media. Retrieved 1 September 2007.

- Heim, Kristi (18 February 2005). "Seattle's packed with Wi-Fi spots". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 1 September 2007.

- Murphy, Niall; Malone, David; Duffy, Ken (25 September 2002). "802.11 Wireless Networking Deployment Survey for Dublin, Ireland" (PDF). Enigma Consulting Technical Report. Retrieved 2 October 2002.

- "Worldwide WarDrive Aftermath – Slashdot".

- "Google-Debatte: Datenschützer kritisieren W-Lan-Kartografie – SPIEGEL ONLINE". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

- "mapping MAC addresses – samy kamkar". Samy.pl. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

- Wei-Meng Lee (27 May 2004). "Wireless Surveying on the Pocket PC". O'Reilly Network. Archived from the original on 19 June 2009. Retrieved 1 September 2007.

- Brenner, Susan (12 February 2006). "Access". CYB3RCRIM3. Retrieved 2 September 2007.

- Bierlein, Matthew (2006). "Policing the Wireless World: Access Liability in the Open Wi-Fi Era" (PDF). Ohio State Law Journal. 67 (5). Retrieved 1 September 2007.

- Ryan, Patrick S. (2004). "War, Peace, or Stalemate: Wargames, Wardialing, Wardriving, and the Emerging Market for Hacker Ethics". Virginia Journal of Law & Technology. 9 (7). SSRN 585867. – Article on the ethics and legality of wardriving

- Kern, Benjamin D. (December 2005). "Whacking, Joyriding and War-Driving: Roaming Use of Wi-Fi and the Law". CIPerati. 2 (4). Retrieved 1 September 2007.

- Alternate PDF – Law review article on the legality of wardriving, piggybacking and accidental use of open networks

- "NetSpot: WiFi Site Survey Software for MAC OS X & Windows".

- "Apple widens App Store bans, Wi-Fi scanners on the chopping block". DVICE. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

- @WardriveOrg. "Wardrive.Org".

- "Web hosting, domain names, VPS - 000webhost.com".

External links

The dictionary definition of wardriving at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of wardriving at Wiktionary