Wi-Fi

Wi-Fi (/ˈwaɪfaɪ/)[1] is a family of wireless network protocols, based on the IEEE 802.11 family of standards, which are commonly used for local area networking of devices and Internet access. Wi‑Fi is a trademark of the non-profit Wi-Fi Alliance, which restricts the use of the term Wi-Fi Certified to products that successfully complete interoperability certification testing.[2][3][4] As of 2017, the Wi-Fi Alliance consisted of more than 800 companies from around the world.[5] As of 2019, over 3.05 billion Wi-Fi enabled devices are shipped globally each year.[6] Devices that can use Wi-Fi technologies include personal computer desktops and laptops, smartphones and tablets, smart TVs, printers, smart speakers, cars, and drones.

Wi-Fi Alliance | |

| Introduced | 21 September 1998 |

|---|---|

| Compatible hardware | Personal computers, gaming consoles, Smart Devices, televisions, printers, mobile phones |

| Part of a series on |

| Antennas |

|---|

|

Wi-Fi uses multiple parts of the IEEE 802 protocol family and is designed to interwork seamlessly with its wired sibling Ethernet. Compatible devices can network through wireless access points to each other as well as to wired devices and the Internet. The different versions of Wi-Fi are specified by various IEEE 802.11 protocol standards, with the different radio technologies determining radio bands, and the maximum ranges, and speeds that may be achieved. Wi-Fi most commonly uses the 2.4 gigahertz (120 mm) UHF and 5 gigahertz (60 mm) SHF ISM radio bands; these bands are subdivided into multiple channels. Channels can be shared between networks but only one transmitter can locally transmit on a channel at any moment in time.

Wi-Fi's wavebands have relatively high absorption and work best for line-of-sight use. Many common obstructions such as walls, pillars, home appliances, etc. may greatly reduce range, but this also helps minimize interference between different networks in crowded environments. An access point (or hotspot) often has a range of about 20 metres (66 feet) indoors while some modern access points claim up to a 150-metre (490-foot) range outdoors. Hotspot coverage can be as small as a single room with walls that block radio waves, or as large as many square kilometres (miles) using many overlapping access points with roaming permitted between them. Over time the speed and spectral efficiency of Wi-Fi have increased. As of 2019, at close range, some versions of Wi-Fi, running on suitable hardware, can achieve speeds of over 1 Gbit/s (gigabit per second).

Wi-Fi is potentially more vulnerable to attack than wired networks because anyone within range of a network with a wireless network interface controller can attempt access. To connect to a Wi-Fi network, a user typically needs the network name (the SSID) and a password. The password is used to encrypt Wi-Fi packets to block eavesdroppers. Wi-Fi Protected Access (WPA) is intended to protect information moving across Wi-Fi networks and includes versions for personal and enterprise networks. Developing security features of WPA have included stronger protections and new security practices. A QR code can be used to automatically configure a mobile phone's Wi-Fi. Modern phones automatically detect a QR code when taking a picture through application software.

History

In 1971, ALOHAnet connected the Great Hawaiian Islands with a UHF wireless packet network. ALOHAnet and the ALOHA protocol were early forerunners to Ethernet, and later the IEEE 802.11 protocols, respectively.

A 1985 ruling by the U.S. Federal Communications Commission released the ISM band for unlicensed use.[7] These frequency bands are the same ones used by equipment such as microwave ovens and are subject to interference.

The technical birthplace of Wi-Fi is The Netherlands.[8] In 1991, NCR Corporation with AT&T Corporation invented the precursor to 802.11, intended for use in cashier systems, under the name WaveLAN. NCR's Vic Hayes, who held the chair of IEEE 802.11 for 10 years, along with Bell Labs Engineer Bruce Tuch, approached IEEE to create a standard and were involved in designing the initial 802.11b and 802.11a standards within the IEEE.[9] They have both been subsequently inducted into the Wi-Fi NOW Hall of Fame.[10]

The first version of the 802.11 protocol was released in 1997, and provided up to 2 Mbit/s link speeds. This was updated in 1999 with 802.11b to permit 11 Mbit/s link speeds, and this proved popular.

In 1999, the Wi-Fi Alliance formed as a trade association to hold the Wi-Fi trademark under which most products are sold.[11]

The major commercial breakthrough came with Apple Inc. adopting Wi-Fi for their iBook series of laptops in 1999. It was the first mass consumer product to offer Wi-Fi network connectivity, which was then branded by Apple as AirPort. This was in collaboration with the same group that helped create the standard Vic Hayes, Bruce Tuch, Cees Links, Rich McGinn, and others from Lucent [12][13][14]

Wi-Fi uses a large number of patents held by many different organizations.[15] In April 2009, 14 technology companies agreed to pay CSIRO $1 billion for infringements on CSIRO patents.[16] This led to Australia labelling Wi-Fi as an Australian invention,[17] though this has been the subject of some controversy.[18][19] CSIRO won a further $220 million settlement for Wi-Fi patent-infringements in 2012, with global firms in the United States required to pay CSIRO licensing rights estimated at an additional $1 billion in royalties.[16][20][21] In 2016, the wireless local area network Test Bed was chosen as Australia's contribution to the exhibition A History of the World in 100 Objects held in the National Museum of Australia.[22]

Etymology and terminology

The name Wi-Fi, commercially used at least as early as August 1999,[23] was coined by the brand-consulting firm Interbrand. The Wi-Fi Alliance had hired Interbrand to create a name that was "a little catchier than 'IEEE 802.11b Direct Sequence'."[24][25] Phil Belanger, a founding member of the Wi-Fi Alliance, has stated that the term Wi-Fi was chosen from a list of ten potential names invented by Interbrand.[26]

The name Wi-Fi has no further meaning, and was never officially a shortened form of "Wireless Fidelity".[27] Nevertheless, the Wi-Fi Alliance used the advertising slogan "The Standard for Wireless Fidelity" for a short time after the brand name was created,[24][28][29] and the Wi-Fi Alliance was also called the "Wireless Fidelity Alliance Inc" in some publications.[30] The name is sometimes written as WiFi, Wifi, or wifi, but these are not approved by the Wi-Fi Alliance. IEEE is a separate, but related, organization and their website has stated "WiFi is a short name for Wireless Fidelity".[31][32]

Interbrand also created the Wi-Fi logo. The yin-yang Wi-Fi logo indicates the certification of a product for interoperability.[28]

Non-Wi-Fi technologies intended for fixed points, such as Motorola Canopy, are usually described as fixed wireless. Alternative wireless technologies include mobile phone standards, such as 2G, 3G, 4G, and LTE.

To connect to a Wi-Fi LAN, a computer must be equipped with a wireless network interface controller. The combination of a computer and an interface controller is called a station. Stations are identified by one or more MAC addresses.

Wi-Fi nodes often operate in infrastructure mode where all communications go through a base station. Ad hoc mode refers to devices talking directly to each other without the need to first talk to an access point.

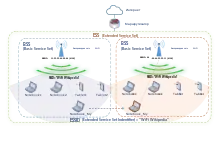

A service set is the set of all the devices associated with a particular Wi-Fi network. Devices in a service set need not be on the same wavebands or channels. A service set can be local, independent, extended, or mesh or a combination.

Each service set has an associated identifier, the 32-byte Service Set Identifier (SSID), which identifies the particular network. The SSID is configured within the devices that are considered part of the network.

A Basic Service Set (BSS) is a group of stations that all share the same wireless channel, SSID, and other wireless settings that have wirelessly connected (usually to the same access point).[33]:3.6 Each BSS is identified by a MAC address which is called the BSSID.

Certification

The IEEE does not test equipment for compliance with their standards. The non-profit Wi-Fi Alliance was formed in 1999 to fill this void—to establish and enforce standards for interoperability and backward compatibility, and to promote wireless local-area-network technology. As of 2017, the Wi-Fi Alliance includes more than 800 companies.[5] It includes VVDN Technologies[34][35], 3Com (now owned by HPE/Hewlett-Packard Enterprise), Aironet (now owned by Cisco), Harris Semiconductor (now owned by Intersil), Lucent (now owned by Nokia), Nokia and Symbol Technologies (now owned by Zebra Technologies).[36][37] The Wi-Fi Alliance enforces the use of the Wi-Fi brand to technologies based on the IEEE 802.11 standards from the IEEE. This includes wireless local area network (WLAN) connections, a device to device connectivity (such as Wi-Fi Peer to Peer aka Wi-Fi Direct), Personal area network (PAN), local area network (LAN), and even some limited wide area network (WAN) connections. Manufacturers with membership in the Wi-Fi Alliance, whose products pass the certification process, gain the right to mark those products with the Wi-Fi logo.

Specifically, the certification process requires conformance to the IEEE 802.11 radio standards, the WPA and WPA2 security standards, and the EAP authentication standard. Certification may optionally include tests of IEEE 802.11 draft standards, interaction with cellular-phone technology in converged devices, and features relating to security set-up, multimedia, and power-saving.[38]

Not every Wi-Fi device is submitted for certification. The lack of Wi-Fi certification does not necessarily imply that a device is incompatible with other Wi-Fi devices.[39] The Wi-Fi Alliance may or may not sanction derivative terms, such as Super Wi-Fi,[40] coined by the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to describe proposed networking in the UHF TV band in the US.[41]

Versions

Equipment frequently support multiple versions of Wi-Fi. To communicate, devices must use a common Wi-Fi version. The versions differ between the radio wavebands they operate on, the radio bandwidth they occupy, the maximum data rates they can support and other details. Some versions permit the use of multiple antennas, which permits greater speeds as well as reduced interference.

Historically, the equipment has simply listed the versions of Wi-Fi using the name of the IEEE standard that it supports. In 2018,[42] the Wi-Fi alliance standardized generational numbering so that equipment can indicate that it supports Wi-Fi 4 (if the equipment supports 802.11n), Wi-Fi 5 (802.11ac) and Wi-Fi 6 (802.11ax). These generations have a high degree of backward compatibility with previous versions. The alliance have stated that the generational level 4, 5, or 6 can be indicated in the user interface when connected, along with the signal strength.[43]

The full list of versions of Wi-Fi is: 802.11a, 802.11b, 802.11g, 802.11n (Wi-Fi 4[43]), 802.11h, 802.11i, 802.11-2007, 802.11-2012, 802.11ac (Wi-Fi 5[43]), 802.11ad, 802.11af, 802.11-2016, 802.11ah, 802.11ai, 802.11aj, 802.11aq, 802.11ax (Wi-Fi 6[43]), 802.11ay.

Uses

Internet

Wi-Fi technology may be used to provide local network and Internet access to devices that are within Wi-Fi range of one or more routers that are connected to the Internet. The coverage of one or more interconnected access points (hotspots) can extend from an area as small as a few rooms to as large as many square kilometres (miles). Coverage in the larger area may require a group of access points with overlapping coverage. For example, public outdoor Wi-Fi technology has been used successfully in wireless mesh networks in London. An international example is Fon.

Wi-Fi provides services in private homes, businesses, as well as in public spaces. Wi-Fi hotspots may be set up either free-of-charge or commercially, often using a captive portal webpage for access. Organizations, enthusiasts, authorities and businesses, such as airports, hotels, and restaurants, often provide free or paid-use hotspots to attract customers, to provide services to promote business in selected areas.

Routers often incorporate a digital subscriber line modem or a cable modem and a Wi-Fi access point, are frequently set up in homes and other buildings, to provide Internet access and internetworking for the structure.

Similarly, battery-powered routers may include a cellular Internet radio modem and a Wi-Fi access point. When subscribed to a cellular data carrier, they allow nearby Wi-Fi stations to access the Internet over 2G, 3G, or 4G networks using the tethering technique. Many smartphones have a built-in capability of this sort, including those based on Android, BlackBerry, Bada, iOS (iPhone), Windows Phone, and Symbian, though carriers often disable the feature, or charge a separate fee to enable it, especially for customers with unlimited data plans. "Internet packs" provide standalone facilities of this type as well, without the use of a smartphone; examples include the MiFi- and WiBro-branded devices. Some laptops that have a cellular modem card can also act as mobile Internet Wi-Fi access points.

Many traditional university campuses in the developed world provide at least partial Wi-Fi coverage. Carnegie Mellon University built the first campus-wide wireless Internet network, called Wireless Andrew, at its Pittsburgh campus in 1993 before Wi-Fi branding originated.[44][45][46] By February 1997, the CMU Wi-Fi zone was fully operational. Many universities collaborate in providing Wi-Fi access to students and staff through the Eduroam international authentication infrastructure.

City-wide

In the early 2000s, many cities around the world announced plans to construct citywide Wi-Fi networks. There are many successful examples; in 2004, Mysore (Mysuru) became India's first Wi-Fi-enabled city. A company called WiFiyNet has set up hotspots in Mysore, covering the whole city and a few nearby villages.[47]

In 2005, St. Cloud, Florida and Sunnyvale, California, became the first cities in the United States to offer citywide free Wi-Fi (from MetroFi).[48] Minneapolis has generated $1.2 million in profit annually for its provider.[49]

In May 2010, the then London mayor Boris Johnson pledged to have London-wide Wi-Fi by 2012.[50] Several boroughs including Westminster and Islington [51][52] already had extensive outdoor Wi-Fi coverage at that point.

Officials in South Korea's capital Seoul are moving to provide free Internet access at more than 10,000 locations around the city, including outdoor public spaces, major streets, and densely populated residential areas. Seoul will grant leases to KT, LG Telecom, and SK Telecom. The companies will invest $44 million in the project, which was to be completed in 2015.[53]

Geolocation

Wi-Fi positioning systems use the positions of Wi-Fi hotspots to identify a device's location.[54]

Operational principles

Wi-Fi stations communicate by sending each other data packets: blocks of data individually sent and delivered over radio. As with all radio, this is done by the modulating and demodulation of carrier waves. Different versions of Wi-Fi use different techniques, 802.11b uses DSSS on a single carrier, whereas 802.11a, Wi-Fi 4, 5 and 6 use multiple carriers on slightly different frequencies within the channel (OFDM).[55][56]

| Generation/IEEE Standard | Maximum Linkrate | Adopted | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wi‑Fi 6E (802.11ax) | 600 to 9608 Mbit/s | 2019 | 6 GHz |

| Wi‑Fi 6 (802.11ax) | 600 to 9608 Mbit/s | 2019 | 2.4/5 GHz |

| Wi‑Fi 5 (802.11ac) | 433 to 6933 Mbit/s | 2014 | 5 GHz |

| Wi‑Fi 4 (802.11n) | 72 to 600 Mbit/s | 2008 | 2.4/5 GHz |

| 802.11g | 6 to 54 Mbit/s | 2003 | 2.4 GHz |

| 802.11a | 6 to 54 Mbit/s | 1999 | 5 GHz |

| 802.11b | 1 to 11 Mbit/s | 1999 | 2.4 GHz |

| 802.11 | 1 to 2 Mbit/s | 1997 | 2.4 GHz |

| (Wi-Fi 1, Wi-Fi 2, Wi-Fi 3, Wi-Fi 3E are unbranded[57] but have unofficial assignments[58]) | |||

As with other IEEE 802 LANs, stations come programmed with a globally unique 48-bit MAC address (often printed on the equipment) so that each Wi-Fi station has a unique address.[lower-alpha 1] The MAC addresses are used to specify both the destination and the source of each data packet. Wi-Fi establishes link-level connections, which can be defined using both the destination and source addresses. On the reception of a transmission, the receiver uses the destination address to determine whether the transmission is relevant to the station or should be ignored. A network interface normally does not accept packets addressed to other Wi-Fi stations.[lower-alpha 2]

Due to the ubiquity of Wi-Fi and the ever-decreasing cost of the hardware needed to support it, most manufacturers now build Wi-Fi interfaces directly into PC motherboards, eliminating the need for installation of a separate network card.

Channels are used half duplex[59][60] and can be time-shared by multiple networks. When communication happens on the same channel, any information sent by one computer is locally received by all, even if that information is intended for just one destination.[lower-alpha 3] The network interface card interrupts the CPU only when applicable packets are received: the card ignores information not addressed to it.[lower-alpha 4] The use of the same channel also means that the data bandwidth is shared, such that, for example, available data bandwidth to each device is halved when two stations are actively transmitting.

A scheme known as carrier sense multiple access with collision avoidance (CSMA/CA) governs the way stations share channels. With CSMA/CA stations attempt to avoid collisions by beginning transmission only after the channel is sensed to be "idle",[61][62] but then transmit their packet data in its entirety. However for geometric reasons, it cannot completely prevent collisions. A collision happens when a station receives multiple signals on a channel at the same time. This corrupts the transmitted data and can require stations to re-transmit. The lost data and re-transmission reduces throughput, in some cases severely.

Waveband

The 802.11 standard provides several distinct radio frequency ranges for use in Wi-Fi communications: 900 MHz, 2.4 GHz, 3.6 GHz, 4.9 GHz, 5 GHz, 5.9 GHz and 60 GHz bands.[63][64][65] Each range is divided into a multitude of channels. In the standards, channels are numbered at 5 MHz spacing within a band (except in the 60 GHz band, where they are 2.16 GHz apart), and the number refers to the centre frequency of the channel. Although channels are numbered at 5 MHz spacing, transmitters generally occupy at least 20 MHz, and standards allow for channels to be bonded together to form wider channels for higher throughput. Those are also numbered by the centre frequency of the bonded group.

Countries apply their own regulations to the allowable channels, allowed users and maximum power levels within these frequency ranges. The ISM band ranges are also often used.[66]

802.11b/g/n can use the 2.4 GHz ISM band, operating in the United States under Part 15 Rules and Regulations. In this frequency band equipment may occasionally suffer interference from microwave ovens, cordless telephones, USB 3.0 hubs, and Bluetooth devices.

Spectrum assignments and operational limitations are not consistent worldwide: Australia and Europe allow for an additional two channels (12, 13) beyond the 11 permitted in the United States for the 2.4 GHz band, while Japan has three more (12–14). In the US and other countries, 802.11a and 802.11g devices may be operated without a licence, as allowed in Part 15 of the FCC Rules and Regulations.

802.11a/h/j/n/ac/ax can use the 5 GHz U-NII band, which, for much of the world, offers at least 23 non-overlapping 20 MHz channels rather than the 2.4 GHz ISM frequency band, where the channels are only 5 MHz wide. In general, lower frequencies have better range but have less capacity. The 5 GHz bands are absorbed to a greater degree by common building materials than the 2.4 GHz bands and usually give a shorter range.

As 802.11 specifications evolved to support higher throughput, the protocols have become much more efficient in their use of bandwidth. Additionally, they have gained the ability to aggregate (or 'bond') channels together to gain still more throughput where the bandwidth is available. 802.11n allows for double radio spectrum/bandwidth (40 MHz- 8 channels) compared to 802.11a or 802.11g (20 MHz). 802.11n can also be set to limit itself to 20 MHz bandwidth to prevent interference in dense communities.[67] In the 5 GHz band, 20 MHz, 40 MHz, 80 MHz, and 160 MHz bandwidth signals are permitted with some restrictions, giving much faster connections.

Communication stack

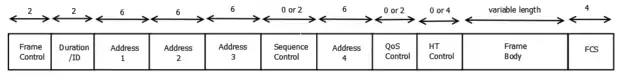

Wi-Fi is part of the IEEE 802 protocol family. The data is organized into 802.11 frames that are very similar to Ethernet frames at the data link layer, but with extra address fields. MAC addresses are used as network addresses for routing over the LAN.[68]

Wi-Fi's MAC and physical layer (PHY) specifications are defined by IEEE 802.11 for modulating and receiving one or more carrier waves to transmit the data in the infrared, and 2.4, 3.6, 5, or 60 GHz frequency bands. They are created and maintained by the IEEE LAN/MAN Standards Committee (IEEE 802). The base version of the standard was released in 1997 and has had many subsequent amendments. The standard and amendments provide the basis for wireless network products using the Wi-Fi brand. While each amendment is officially revoked when it is incorporated in the latest version of the standard, the corporate world tends to market to the revisions because they concisely denote capabilities of their products.[69] As a result, in the market place, each revision tends to become its own standard.

In addition to 802.11 the IEEE 802 protocol family has specific provisions for Wi-Fi. These are required because Ethernet's cable-based media are not usually shared, whereas with wireless all transmissions are received by all stations within the range that employ that radio channel. While Ethernet has essentially negligible error rates, wireless communication media are subject to significant interference. Therefore, the accurate transmission is not guaranteed so delivery is, therefore, a best-effort delivery mechanism. Because of this, for Wi-Fi, the Logical Link Control (LLC) specified by IEEE 802.2 employs Wi-Fi's media access control (MAC) protocols to manage retries without relying on higher levels of the protocol stack.[70]

For internetworking purposes, Wi-Fi is usually layered as a link layer (equivalent to the physical and data link layers of the OSI model) below the internet layer of the Internet Protocol. This means that nodes have an associated internet address and, with suitable connectivity, this allows full Internet access.

Infrastructure

In infrastructure mode, which is the most common mode used, all communications go through a base station. For communications within the network, this introduces an extra use of the airwaves but has the advantage that any two stations that can communicate with the base station can also communicate through the base station, which enormously simplifies the protocols.

Ad hoc and Wi-Fi direct

Wi-Fi also allows communications directly from one computer to another without an access point intermediary. This is called ad hoc Wi-Fi transmission. Different types of ad hoc networks exist. In the simplest case network nodes must talk directly to each other. In more complex protocols nodes may forward packets, and nodes keep track of how to reach other nodes, even if they move around.

Ad hoc mode was first described by Chai Keong Toh in his 1996 patent[71] of Wi-Fi ad hoc routing, implemented on Lucent WaveLAN 802.11a wireless on IBM ThinkPads over a size nodes scenario spanning a region of over a mile. The success was recorded in Mobile Computing magazine (1999)[72] and later published formally in IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications, 2002[73] and ACM SIGMETRICS Performance Evaluation Review, 2001.[74]

This wireless ad hoc network mode has proven popular with multiplayer handheld game consoles, such as the Nintendo DS, PlayStation Portable, digital cameras, and other consumer electronics devices. Some devices can also share their Internet connection using ad hoc, becoming hotspots or "virtual routers".[75]

Similarly, the Wi-Fi Alliance promotes the specification Wi-Fi Direct for file transfers and media sharing through a new discovery- and security-methodology.[76] Wi-Fi Direct launched in October 2010.[77]

Another mode of direct communication over Wi-Fi is Tunneled Direct-Link Setup (TDLS), which enables two devices on the same Wi-Fi network to communicate directly, instead of via the access point.[78]

Multiple access points

An Extended Service Set may be formed by deploying multiple access points that are configured with the same SSID and security settings. Wi-Fi client devices typically connect to the access point that can provide the strongest signal within that service set.[79]

Increasing the number of Wi-Fi access points for a network provides redundancy, better range, support for fast roaming, and increased overall network-capacity by using more channels or by defining smaller cells. Except for the smallest implementations (such as home or small office networks), Wi-Fi implementations have moved toward "thin" access points, with more of the network intelligence housed in a centralized network appliance, relegating individual access points to the role of "dumb" transceivers. Outdoor applications may use mesh topologies.

Performance

Wi-Fi operational range depends on factors such as the frequency band, radio power output, receiver sensitivity, antenna gain, and antenna type as well as the modulation technique. Also, the propagation characteristics of the signals can have a big impact.

At longer distances, and with greater signal absorption, speed is usually reduced.

Transmitter power

Compared to cell phones and similar technology, Wi-Fi transmitters are low power devices. In general, the maximum amount of power that a Wi-Fi device can transmit is limited by local regulations, such as FCC Part 15 in the US. Equivalent isotropically radiated power (EIRP) in the European Union is limited to 20 dBm (100 mW).

To reach requirements for wireless LAN applications, Wi-Fi has higher power consumption compared to some other standards designed to support wireless personal area network (PAN) applications. For example, Bluetooth provides a much shorter propagation range between 1 and 100 metres (1 and 100 yards)[80] and so in general has a lower power consumption. Other low-power technologies such as ZigBee have fairly long range, but much lower data rate. The high power consumption of Wi-Fi makes battery life in some mobile devices a concern.

Antenna

An access point compliant with either 802.11b or 802.11g, using the stock omnidirectional antenna might have a range of 100 m (0.062 mi). The same radio with an external semi parabolic antenna (15 dB gain) with a similarly equipped receiver at the far end might have a range over 20 miles.

Higher gain rating (dBi) indicates further deviation (generally toward the horizontal) from a theoretical, perfect isotropic radiator, and therefore the antenna can project or accept a usable signal further in particular directions, as compared to a similar output power on a more isotropic antenna.[81] For example, an 8 dBi antenna used with a 100 mW driver has a similar horizontal range to a 6 dBi antenna being driven at 500 mW. Note that this assumes that radiation in the vertical is lost; this may not be the case in some situations, especially in large buildings or within a waveguide. In the above example, a directional waveguide could cause the low power 6 dBi antenna to project much further in a single direction than the 8 dBi antenna, which is not in a waveguide, even if they are both driven at 100 mW.

On wireless routers with detachable antennas, it is possible to improve range by fitting upgraded antennas that provide a higher gain in particular directions. Outdoor ranges can be improved to many kilometres (miles) through the use of high gain directional antennas at the router and remote device(s).

MIMO (multiple-input and multiple-output)

Wi-Fi 4 and higher standards allow devices to have multiple antennas on transmitters and receivers. Multiple antennas enable the equipment to exploit multipath propagation on the same frequency bands giving much faster speeds and greater range.

Wi-Fi 4 can more than double the range over previous standards.[82]

The Wi-Fi 5 standard uses the 5 GHz band exclusively, and is capable of multi-station WLAN throughput of at least 1 gigabit per second, and a single station throughput of at least 500 Mbit/s. As of the first quarter of 2016, The Wi-Fi Alliance certifies devices compliant with the 802.11ac standard as "Wi-Fi CERTIFIED ac". This standard uses several signal processing techniques such as multi-user MIMO and 4X4 Spatial Multiplexing streams, and wide channel bandwidth (160 MHz) to achieve its gigabit throughput. According to a study by IHS Technology, 70% of all access point sales revenue in the first quarter of 2016 came from 802.11ac devices.[83]

Radio propagation

With Wi-Fi signals line-of-sight usually works best, but signals can transmit, absorb, reflect, refract, diffract and up and down fade through and around structures, both man-made and natural.

Due to the complex nature of radio propagation at typical Wi-Fi frequencies, particularly around trees and buildings, algorithms can only approximately predict Wi-Fi signal strength for any given area in relation to a transmitter.[84] This effect does not apply equally to long-range Wi-Fi, since longer links typically operate from towers that transmit above the surrounding foliage.

Mobile use of Wi-Fi over wider ranges is limited, for instance, to uses such as in an automobile moving from one hotspot to another. Other wireless technologies are more suitable for communicating with moving vehicles.

- Distance records

Distance records (using non-standard devices) include 382 km (237 mi) in June 2007, held by Ermanno Pietrosemoli and EsLaRed of Venezuela, transferring about 3 MB of data between the mountain-tops of El Águila and Platillon.[85][86] The Swedish Space Agency transferred data 420 km (260 mi), using 6 watt amplifiers to reach an overhead stratospheric balloon.[87]

Interference

Wi-Fi connections can be blocked or the Internet speed lowered by having other devices in the same area. Wi-Fi protocols are designed to share the wavebands reasonably fairly, and this often works with little to no disruption. To minimize collisions with Wi-Fi and non-Wi-Fi devices, Wi-Fi employs Carrier-sense multiple access with collision avoidance (CSMA/CA), where transmitters listen before transmitting and delay transmission of packets if they detect that other devices are active on the channel, or if noise is detected from adjacent channels or non-Wi-Fi sources. Nevertheless, Wi-Fi networks are still susceptible to the hidden node and exposed node problem.[88]

A standard speed Wi-Fi signal occupies five channels in the 2.4 GHz band. Interference can be caused by overlapping channels. Any two channel numbers that differ by five or more, such as 2 and 7, do not overlap (no adjacent-channel interference). The oft-repeated adage that channels 1, 6, and 11 are the only non-overlapping channels is, therefore, not accurate. Channels 1, 6, and 11 are the only group of three non-overlapping channels in North America. However, whether the overlap is significant depends on physical spacing. Channels that are four apart interfere a negligible amount-much less than reusing channels (which causes co-channel interference)-if transmitters are at least a few metres (yards) apart.[89] In Europe and Japan where channel 13 is available, using Channels 1, 5, 9, and 13 for 802.11g and 802.11n is recommended.

However, many 2.4 GHz 802.11b and 802.11g access-points default to the same channel on initial startup, contributing to congestion on certain channels. Wi-Fi pollution, or an excessive number of access points in the area, can prevent access and interfere with other devices' use of other access points as well as with decreased signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) between access points. These issues can become a problem in high-density areas, such as large apartment complexes or office buildings with many Wi-Fi access points.[90]

Other devices use the 2.4 GHz band: microwave ovens, ISM band devices, security cameras, ZigBee devices, Bluetooth devices, video senders, cordless phones, baby monitors,[91] and, in some countries, amateur radio, all of which can cause significant additional interference. It is also an issue when municipalities[92] or other large entities (such as universities) seek to provide large area coverage. On some 5 GHz bands interference from radar systems can occur in some places. For base stations that support those bands they employ Dynamic Frequency Selection which listens for radar, and if it is found, it will not permit a network on that band.

These bands can be used by low power transmitters without a licence, and with few restrictions. However, while unintended interference is common, users that have been found to cause deliberate interference (particularly for attempting to locally monopolize these bands for commercial purposes) have been issued large fines.[93]

Throughput

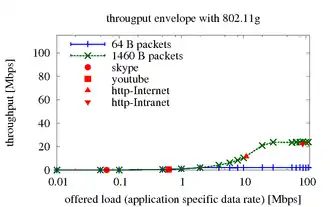

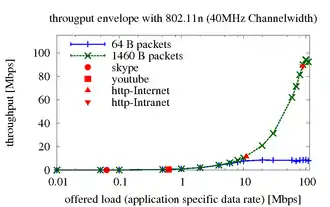

Various layer 2 variants of IEEE 802.11 have different characteristics. Across all flavours of 802.11, maximum achievable throughputs are either given based on measurements under ideal conditions or in the layer 2 data rates. This, however, does not apply to typical deployments in which data are transferred between two endpoints of which at least one is typically connected to a wired infrastructure, and the other is connected to an infrastructure via a wireless link.

This means that typically data frames pass an 802.11 (WLAN) medium and are being converted to 802.3 (Ethernet) or vice versa.

Due to the difference in the frame (header) lengths of these two media, the packet size of an application determines the speed of the data transfer. This means that an application that uses small packets (e.g., VoIP) creates a data flow with high overhead traffic (low goodput).

Other factors that contribute to the overall application data rate are the speed with which the application transmits the packets (i.e., the data rate) and the energy with which the wireless signal is received. The latter is determined by distance and by the configured output power of the communicating devices.[94][95]

The same references apply to the attached throughput graphs, which show measurements of UDP throughput measurements. Each represents an average throughput of 25 measurements (the error bars are there, but barely visible due to the small variation), is with specific packet size (small or large), and with a specific data rate (10 kbit/s – 100 Mbit/s). Markers for traffic profiles of common applications are included as well. This text and measurements do not cover packet errors but information about this can be found at the above references. The table below shows the maximum achievable (application-specific) UDP throughput in the same scenarios (same references again) with various WLAN (802.11) flavours. The measurement hosts have been 25 metres (yards) apart from each other; loss is again ignored.

Hardware

Wi-Fi allows wireless deployment of local area networks (LANs). Also, spaces where cables cannot be run, such as outdoor areas and historical buildings, can host wireless LANs. However, building walls of certain materials, such as stone with high metal content, can block Wi-Fi signals.

A Wi-Fi device is a short-range wireless device. Wi-Fi devices are fabricated on RF CMOS integrated circuit (RF circuit) chips.[96]

Since the early 2000s, manufacturers are building wireless network adapters into most laptops. The price of chipsets for Wi-Fi continues to drop, making it an economical networking option included in ever more devices.[97]

Different competitive brands of access points and client network-interfaces can inter-operate at a basic level of service. Products designated as "Wi-Fi Certified" by the Wi-Fi Alliance are backward compatible. Unlike mobile phones, any standard Wi-Fi device works anywhere in the world.

Access point

A wireless access point (WAP) connects a group of wireless devices to an adjacent wired LAN. An access point resembles a network hub, relaying data between connected wireless devices in addition to a (usually) single connected wired device, most often an Ethernet hub or switch, allowing wireless devices to communicate with other wired devices.

Wireless adapter

Wireless adapters allow devices to connect to a wireless network. These adapters connect to devices using various external or internal interconnects such as PCI, miniPCI, USB, ExpressCard, Cardbus, and PC Card. As of 2010, most newer laptop computers come equipped with built-in internal adapters.

Router

Wireless routers integrate a Wireless Access Point, Ethernet switch, and internal router firmware application that provides IP routing, NAT, and DNS forwarding through an integrated WAN-interface. A wireless router allows wired and wireless Ethernet LAN devices to connect to a (usually) single WAN device such as a cable modem, DSL modem, or optical modem. A wireless router allows all three devices, mainly the access point and router, to be configured through one central utility. This utility is usually an integrated web server that is accessible to wired and wireless LAN clients and often optionally to WAN clients. This utility may also be an application that is run on a computer, as is the case with as Apple's AirPort, which is managed with the AirPort Utility on macOS and iOS.[98]

Bridge

Wireless network bridges can act to connect two networks to form a single network at the data-link layer over Wi-Fi. The main standard is the wireless distribution system (WDS).

Wireless bridging can connect a wired network to a wireless network. A bridge differs from an access point: an access point typically connects wireless devices to one wired network. Two wireless bridge devices may be used to connect two wired networks over a wireless link, useful in situations where a wired connection may be unavailable, such as between two separate homes or for devices that have no wireless networking capability (but have wired networking capability), such as consumer entertainment devices; alternatively, a wireless bridge can be used to enable a device that supports a wired connection to operate at a wireless networking standard that is faster than supported by the wireless network connectivity feature (external dongle or inbuilt) supported by the device (e.g., enabling Wireless-N speeds (up to the maximum supported speed on the wired Ethernet port on both the bridge and connected devices including the wireless access point) for a device that only supports Wireless-G). A dual-band wireless bridge can also be used to enable 5 GHz wireless network operation on a device that only supports 2.4 GHz wireless and has a wired Ethernet port.

Wireless range-extenders or wireless repeaters can extend the range of an existing wireless network. Strategically placed range-extenders can elongate a signal area or allow for the signal area to reach around barriers such as those pertaining in L-shaped corridors. Wireless devices connected through repeaters suffer from an increased latency for each hop, and there may be a reduction in the maximum available data throughput. Besides, the effect of additional users using a network employing wireless range-extenders is to consume the available bandwidth faster than would be the case whereby a single user migrates around a network employing extenders. For this reason, wireless range-extenders work best in networks supporting low traffic throughput requirements, such as for cases whereby a single user with a Wi-Fi-equipped tablet migrates around the combined extended and non-extended portions of the total connected network. Also, a wireless device connected to any of the repeaters in the chain has data throughput limited by the "weakest link" in the chain between the connection origin and connection end. Networks using wireless extenders are more prone to degradation from interference from neighbouring access points that border portions of the extended network and that happen to occupy the same channel as the extended network.

Embedded systems

The security standard, Wi-Fi Protected Setup, allows embedded devices with a limited graphical user interface to connect to the Internet with ease. Wi-Fi Protected Setup has 2 configurations: The Push Button configuration and the PIN configuration. These embedded devices are also called The Internet of Things and are low-power, battery-operated embedded systems. Several Wi-Fi manufacturers design chips and modules for embedded Wi-Fi, such as GainSpan.[99]

Increasingly in the last few years (particularly as of 2007), embedded Wi-Fi modules have become available that incorporate a real-time operating system and provide a simple means of wirelessly enabling any device that can communicate via a serial port.[100] This allows the design of simple monitoring devices. An example is a portable ECG device monitoring a patient at home. This Wi-Fi-enabled device can communicate via the Internet.[101]

These Wi-Fi modules are designed by OEMs so that implementers need only minimal Wi-Fi knowledge to provide Wi-Fi connectivity for their products.

In June 2014, Texas Instruments introduced the first ARM Cortex-M4 microcontroller with an onboard dedicated Wi-Fi MCU, the SimpleLink CC3200. It makes embedded systems with Wi-Fi connectivity possible to build as single-chip devices, which reduces their cost and minimum size, making it more practical to build wireless-networked controllers into inexpensive ordinary objects.[102]

Network security

The main issue with wireless network security is its simplified access to the network compared to traditional wired networks such as Ethernet. With wired networking, one must either gain access to a building (physically connecting into the internal network), or break through an external firewall. To access Wi-Fi, one must merely be within the range of the Wi-Fi network. Most business networks protect sensitive data and systems by attempting to disallow external access. Enabling wireless connectivity reduces security if the network uses inadequate or no encryption.[103][104][105]

An attacker who has gained access to a Wi-Fi network router can initiate a DNS spoofing attack against any other user of the network by forging a response before the queried DNS server has a chance to reply.[106]

Securing methods

A common measure to deter unauthorized users involves hiding the access point's name by disabling the SSID broadcast. While effective against the casual user, it is ineffective as a security method because the SSID is broadcast in the clear in response to a client SSID query. Another method is to only allow computers with known MAC addresses to join the network,[107] but determined eavesdroppers may be able to join the network by spoofing an authorized address.

Wired Equivalent Privacy (WEP) encryption was designed to protect against casual snooping but it is no longer considered secure. Tools such as AirSnort or Aircrack-ng can quickly recover WEP encryption keys.[108] Because of WEP's weakness the Wi-Fi Alliance approved Wi-Fi Protected Access (WPA) which uses TKIP. WPA was specifically designed to work with older equipment usually through a firmware upgrade. Though more secure than WEP, WPA has known vulnerabilities.

The more secure WPA2 using Advanced Encryption Standard was introduced in 2004 and is supported by most new Wi-Fi devices. WPA2 is fully compatible with WPA.[109] In 2017, a flaw in the WPA2 protocol was discovered, allowing a key replay attack, known as KRACK.[110][111]

A flaw in a feature added to Wi-Fi in 2007, called Wi-Fi Protected Setup (WPS), let WPA and WPA2 security be bypassed, and effectively broken in many situations. The only remedy as of late 2011 was to turn off Wi-Fi Protected Setup,[112] which is not always possible.

Virtual Private Networks can be used to improve the confidentiality of data carried through Wi-Fi networks, especially public Wi-Fi networks.[113]

Data security risks

The older wireless encryption-standard, Wired Equivalent Privacy (WEP), has been shown easily breakable even when correctly configured. Wi-Fi Protected Access (WPA and WPA2) encryption, which became available in devices in 2003, aimed to solve this problem. Wi-Fi access points typically default to an encryption-free (open) mode. Novice users benefit from a zero-configuration device that works out-of-the-box, but this default does not enable any wireless security, providing open wireless access to a LAN. To turn security on requires the user to configure the device, usually via a software graphical user interface (GUI). On unencrypted Wi-Fi networks connecting devices can monitor and record data (including personal information). Such networks can only be secured by using other means of protection, such as a VPN or secure Hypertext Transfer Protocol over Transport Layer Security (HTTPS).

Wi-Fi Protected Access encryption (WPA2) is considered secure, provided a strong passphrase is used. In 2018, WPA3 was announced as a replacement for WPA2, increasing security;[114] it rolled out on June 26.[115]

Piggybacking

Piggybacking refers to access to a wireless Internet connection by bringing one's computer within the range of another's wireless connection, and using that service without the subscriber's explicit permission or knowledge.

During the early popular adoption of 802.11, providing open access points for anyone within range to use was encouraged to cultivate wireless community networks,[116] particularly since people on average use only a fraction of their downstream bandwidth at any given time.

Recreational logging and mapping of other people's access points have become known as wardriving. Indeed, many access points are intentionally installed without security turned on so that they can be used as a free service. Providing access to one's Internet connection in this fashion may breach the Terms of Service or contract with the ISP. These activities do not result in sanctions in most jurisdictions; however, legislation and case law differ considerably across the world. A proposal to leave graffiti describing available services was called warchalking.[117]

Piggybacking often occurs unintentionally – a technically unfamiliar user might not change the default "unsecured" settings to their access point and operating systems can be configured to connect automatically to any available wireless network. A user who happens to start up a laptop in the vicinity of an access point may find the computer has joined the network without any visible indication. Moreover, a user intending to join one network may instead end up on another one if the latter has a stronger signal. In combination with automatic discovery of other network resources (see DHCP and Zeroconf) this could lead wireless users to send sensitive data to the wrong middle-man when seeking a destination (see man-in-the-middle attack). For example, a user could inadvertently use an unsecured network to log into a website, thereby making the login credentials available to anyone listening, if the website uses an insecure protocol such as plain HTTP without TLS.

An unauthorized user can obtain security information (factory preset passphrase and/or Wi-Fi Protected Setup PIN) from a label on a wireless access point can use this information (or connect by the Wi-Fi Protected Setup pushbutton method) to commit unauthorized and/or unlawful activities.

Societal Aspects

Wireless internet access has become much more embedded in society. As of 2020, “53 percent of US Internet users would find it "very hard" to give up Web access, up from 38 percent in 2006.”[118] It has thus changed how the society functions in many ways.

Digital Divide

It has previously been found that access to computers and the Internet have created a digital divide across the world. In 1997, research conducted by the National Telecommunications and Information Administration [119] in the US suggested that a divide based on ethnicity was present with regards to owning a personal computer and having online access. The household structure also had an impact, and households with children under the age of 15 and where women were the head of the family were falling behind. Besides, people with higher education were more likely to have access to the internet, than those who did not.[120] In later studies conducted by The United States Department of Commerce (2000 and 2002) and by The United States Department of Labor Statistics (2004) it is shown that the digital divide was beginning to grow smaller.[121][122][123] A reason for this may be the use of Wi-Fi.[124]

Early research showed how gender could impact the use of computers, and that many technologies were male-oriented.[125] It also shows that more men have access to broadband connections[126] and therefore more men use wireless high-speed connections. In later research this divide has gone down however, and even shows that a higher percentage of women are online than men.[127][128] A reason that the digital divide has gone down based on gender, is argued to be the growing access to Wi-Fi and therefore, the internet.[125][129]

With regards to the digital divide based on ethnicity, research suggests that Hispanics and Blacks are less likely to be online or own a computer.[130][131] A study conducted by Horrigan in 2007[127] also found that 67 percent of the users using a wireless connection to access the internet were White, 12 percent were Black and 14 percent were Hispanic. On the other hand, it can seem like the digital divide based on ethnicity is growing smaller. Hispanics who already have online access are adopting new technology at a higher rate than the general population.[132] Blacks are also adopting broadband technology rapidly and increasing their use of the internet.[133][134]

Another aspect of the digital divide is age. Older generations are less likely to use the internet through a wireless connection, while younger people are the fastest at adopting wireless technologies. People who are between 50–64 years old or 65 years and older are less likely to access the internet through a wireless connection at a user group of 19 and 3 percent respectively.[127] There are in comparison 30 percent of people between 18–29 years old and 49 percent of people between 30–49 years old who access the internet via Wi-Fi.[135]

Influence on Developing Countries

Over half the world does not have access to the internet,[136] prominently rural areas in developing nations. Technology that has been implemented in more developed nations is often costly and low energy efficient. This has led to developing nations using more low-tech networks, frequently implementing renewable power sources that can solely be maintained through solar power, creating a network that is resistant to disruptions such as power outages. For instance, in 2007 a 450 km (280 mile) network between Cabo Pantoja and Iquitos in Peru was erected in which all equipment is powered only by solar panels.[136] These long-range Wi-Fi networks have two main uses: offer internet access to populations in isolated villages, and to provide healthcare to isolated communities. In the case of the aforementioned example, it connects the central hospital in Iquitos to 15 medical outposts which are intended for remote diagnosis.[136]

Students and Learning

A study by Ellore et al.[137] shows that online media for education and non-education was found to have a non-significant relationship with academic performance. Their results infer that students do not get distracted from their academic responsibilities by watching or listening to content online and seem to effectively manage available time. The study also provides evidence that spending time on Facebook does not seem to adversely affect the academic performance of a student.

Work Habits

Access to Wi-Fi in public spaces such as cafes or parks allows people, in particular freelancers, to work remotely.[138] An article from 2009 notes that the availability of wireless access allows people to choose from a wide range of places to work in. While the accessibility of Wi-Fi is the strongest factor when choosing a place to work (75% of people would choose a place that provides Wi-Fi over one that does not),[138] other factors influence the choice of specific hotspot. These vary from the accessibility of other resources, like books, the location of the workplace, and the social aspect of meeting other people in the same place. Moreover, the increase of people working from public places results in more customers for local businesses thus providing an economic stimulus to the area.

Additionally, in the same study it has been noted that wireless connection provides more freedom of movement while working. Both when working at home or from the office it allows the displacement between different rooms or areas. In some offices (notably Cisco offices in New York) the employees do not have assigned desks but can work from any office connecting their laptop to Wi-Fi hotspot.[138]

Housing

The internet has become an integral part of living. 81.9% of American households have internet access.[139] Additionally, 89% of American households with broadband connect via wireless technologies.[140] Therefore, 72.9% of American households have Wi-Fi.

Real estate agents report a growing number of buyers that refuse to buy houses that do not have high-speed internet.[141] This can be reflected in home prices related to its access to high speed internet.

Between the years of 2011 and 2013, a study was conducted by the University of Colorado which compared the prices of 520,000 homes. This study, as well as studies conducted by the University of Wisconsin, found that having access to the internet could add $11,815 to the value of a $439,000 vacation house.[141]

Furthermore, fiber optic connection, the highest speed internet connection that exists as of 2020, can add, according to the study by the University of Colorado and Carnegie Mellon, $5,437 to the price of a $175,000 home.[141]

Wi-Fi networks have also affected how the interior of homes and hotels are arranged. For instance, architects have described that their clients no longer wanted only one room as their home office, but would like to work near the fireplace or have the possibility to work in different rooms. This contradicts architect's pre-existing ideas of the use of rooms that they designed. Additionally, some hotels have noted that guests prefer to stay in certain rooms since they receive a stronger Wi-Fi network.[138]

Health concerns

The World Health Organization (WHO) says, "no health effects are expected from exposure to RF fields from base stations and wireless networks", but notes that they promote research into effects from other RF sources.[142][143] (a category used when "a causal association is considered credible, but when chance, bias or confounding cannot be ruled out with reasonable confidence"),[144] this classification was based on risks associated with wireless phone use rather than Wi-Fi networks.

The United Kingdom's Health Protection Agency reported in 2007 that exposure to Wi-Fi for a year results in the "same amount of radiation from a 20-minute mobile phone call".[145]

A review of studies involving 725 people who claimed electromagnetic hypersensitivity, "...suggests that 'electromagnetic hypersensitivity' is unrelated to the presence of an EMF, although more research into this phenomenon is required."[146]

Alternatives

Several other "wireless" technologies provide alternatives to Wi-Fi in some cases:

- Bluetooth, short-distance network

- Bluetooth Low Energy, a low-power variant

- Zigbee, low-power, low data rate, and proximity

- Cellular networks, as used by smartphones

- WiMax, provide wireless internet connection from outside individual homes

Some alternatives are "no new wires", re-using existing cable:

- G.hn over existing home wiring, such as phone and power lines

Several wired technologies for computer networking provide, in some cases, viable alternatives—in particular:

See also

- Gi-Fi—a term used by some trade press to refer to faster versions of the IEEE 802.11 standards

- HiperLAN

- Indoor positioning system

- Li-Fi

- List of WLAN channels

- Operating system Wi-Fi support

- Power-line communication

- San Francisco Digital Inclusion Strategy

- WiGig

- Wireless Broadband Alliance

- Wi-Fi Direct

- Hotspot (Wi-Fi)

- Bluetooth

References

- Garber, Megan (23 June 2014). "'Why-Fi' or 'Wiffy'? How Americans Pronounce Common Tech Terms". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 15 June 2018.

- Beal, Vangie. "What is Wi-Fi (IEEE 802.11x)? A Webopedia Definition". Webopedia. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012.

- Schofield, Jack (21 May 2007). "The dangers of Wi-Fi radiation (updated)" – via www.theguardian.com.

- "Certification | Wi-Fi Alliance". www.wi-fi.org.

- "History | Wi-Fi Alliance". Wi-Fi Alliance. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- "Global Wi-Fi Enabled Devices Shipment Forecast, 2020 - 2024". Research and Markets. 1 July 2020. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- "Authorization of Spread Spectrum Systems Under Parts 15 and 90 of the FCC Rules and Regulations". Federal Communications Commission of the USA. 18 June 1985. Archived from the original (txt) on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 31 August 2007.

- https://wifinowglobal.com/news-and-blog/how-a-meeting-with-steve-jobs-in-1998-gave-birth-to-wi-fi/

- Ben Charny (6 December 2002). "Vic Hayes - Wireless Vision". CNET. Archived from the original on 26 August 2012. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- "Vic Hayes & Bruce Tuch inducted into the Wi-Fi NOW Hall of Fame". Wi-Fi Now. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- "Wi-Fi Alliance: Organization". Official industry association Web site. Archived from the original on 3 September 2009. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- Steve Lohr (22 July 1999). "Apple Offers iMac's Laptop Offspring, the iBook". The New York Times.

- Peter H. Lewis (25 November 1999). "STATE OF THE ART; Not Born To Be Wired". The New York Times.

- Claus Hetting (19 August 2018). "How a meeting with Steve Jobs in 1998 gave birth to Wi-Fi". Wi-Fi Now.

- "IEEE SA - Records of IEEE Standards-Related Patent Letters of Assurance". standards.ieee.org. Archived from the original on 10 April 2012.

- Moses, Asher (1 June 2010). "CSIRO to reap 'lazy billion' from world's biggest tech companies". The Age. Melbourne. Archived from the original on 4 June 2010. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- "World changing Aussie inventions". Australian Geographic. Archived from the original on 15 December 2011.

- Mullin, Joe (4 April 2012). "How the Aussie government "invented WiFi" and sued its way to $430 million". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 8 May 2012.

- Popper, Ben (3 June 2010). "Australia's Biggest Patent Troll Goes After AT&T, Verizon and T-Mobile". CBS News. Archived from the original on 6 May 2013.

- Schubert, Misha (31 March 2012). "Australian scientists cash in on Wi-Fi invention". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 1 April 2012.

- "CSIRO wins legal battle over wi-fi patent". ABC News. 1 April 2012.

- Sibthorpe, Clare (4 August 2016). "CSIRO Wi-Fi invention to feature in upcoming exhibition at National Museum of Australia". The Canberra Times. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- "Statement of Use, s/n 75799629, US Patent and Trademark Office Trademark Status and Document Retrieval". 23 August 2005. Archived from the original on 28 April 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

first used the Certification Mark … as early as August 1999

- Doctorow, Cory (8 November 2005). "WiFi isn't short for "Wireless Fidelity"". Boing Boing. Archived from the original on 21 December 2012. Retrieved 21 December 2012.

- Graychase, Naomi (27 April 2007). "'Wireless Fidelity' Debunked". Wi-Fi Planet. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 31 August 2007.

- Doctorow, Cory (8 November 2005). "WiFi isn't short for "Wireless Fidelity"". Boing Boing. Archived from the original on 20 June 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- Pogue, David (1 May 2012). "What Wi-Fi Stands for—and Other Wireless Questions Answered". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 16 November 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- "Securing Wi-Fi Wireless Networks with Today's Technologies" (PDF). Wi-Fi Alliance. 6 February 2003. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- "WPA Deployment Guidelines for Public Access Wi-Fi Networks" (PDF). Wi-Fi Alliance. 28 October 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 March 2007. Retrieved 30 November 2009.

- HTC S710 User Manual. High Tech Computer Corp. 2006. p. 2.

Wi-Fi is a registered trademark of the Wireless Fidelity Alliance, Inc.

- Varma, Vijay K. "Wireless Fidelity—WiFi" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 August 2017. Retrieved 16 October 2016. (originally published 2006)

- Aime, Marco; Calandriello, Giorgio; Lioy, Antonio (2007). "Dependability in Wireless Networks: Can We Rely on WiFi?" (PDF). IEEE Security and Privacy Magazine. 5 (1): 23–29. doi:10.1109/MSP.2007.4.

- "IEEE 802.11-2007: Wireless LAN Medium Access Control (MAC) and Physical Layer (PHY) specifications". IEEE Standards Association. 8 March 2007. Archived from the original on 18 April 2007.

- "Wi-Fi 6, 11ax & 11ac Access Points, SD-WAN Solutions". VVDN Tech.

- "Wi-Fi Alliance VVDN". Twitter.

- The Wi-Fi Alliance also developed technology that expanded the applicability of Wi-Fi, including a simple set up protocol (Wi-Fi Protected Set Up) and a peer to peer connectivity technology (Wi-Fi Peer to Peer) "Wi-Fi Alliance: Organization". www.wi-fi.org. Archived from the original on 3 September 2009. Retrieved 22 October 2009.

- "Wi-Fi Alliance: White Papers". www.wi-fi.org. Archived from the original on 7 October 2009. Retrieved 22 October 2009.

- "Wi-Fi Alliance: Programs". www.wi-fi.org. Archived from the original on 25 November 2009. Retrieved 22 October 2009.

- "Wi-Fi Alliance". TechTarget. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- "Wi-Fi Alliance® statement regarding "Super Wi-Fi"". Wi-Fi Alliance. Archived from the original on 9 April 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- Sascha Segan (27 January 2012). "'Super Wi-Fi': Super, But Not Wi-Fi". PC Magazine. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- "Wi-Fi Alliance® introduces Wi-Fi 6". Wi-Fi Alliance. 3 October 2018. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- Generational Wi-Fi® User Guide, Wi-Fi Alliance, October 2018

- Smit, Deb (5 October 2011). "How Wi-Fi got its start on the campus of CMU, a true story". Pop City. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- "Wireless Andrew: Creating the World's First Wireless Campus". Carnegie Mellon University. 2007. Archived from the original on 1 September 2011. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- Lemstra, Wolter; Hayes, Vic; Groenewegen, John (2010). The Innovation Journey of Wi-Fi: The Road to Global Success. Cambridge University Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-521-19971-1. Archived from the original on 12 November 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- Verma, Veruna (20 August 2006). "Say Hello to India's First Wirefree City". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 20 January 2012.

- "Sunnyvale Uses Metro Fi" (in Turkish). besttech.com.tr. Archived from the original on 22 July 2015.

- Alexander, Steve; Brandt, Steve (5 December 2010). "Minneapolis moves ahead with wireless". The Star Tribune. Archived from the original on 9 December 2010.

- "London-wide wi-fi by 2012 pledge". BBC News. 19 May 2010. Archived from the original on 22 May 2010. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- Bsu, Indrajit (14 May 2007). "City of London Fires Up Europe's Most Advanced Wi-Fi Network". Digital Communities. Archived from the original on 7 September 2008. Retrieved 14 May 2007.

- Wearden, Graeme (18 April 2005). "London gets a mile of free Wi-Fi". ZDNet. Archived from the original on 7 November 2015. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- "Seoul Moves to Provide Free City-Wide WiFi Service". Voice of America. 15 June 2011. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- Krzysztof W. Kolodziej; Johan Hjelm (19 December 2017). Local Positioning Systems: LBS Applications and Services. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-0500-4.

- Cisco Systems, Inc. White Paper Capacity, Coverage, and Deployment Considerations for IEEE 802.11g

- "802.11ac: A Survival Guide". Chimera.labs.oreilly.com. Archived from the original on 3 July 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- Kastrenakes, Jacob (3 October 2018). "Wi-Fi now has version numbers, and Wi-Fi 6 comes out next year". The Verge. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- "Understand Wi-Fi 4/5/6/6E (802.11 n/ac/ax)". Duckware. 21 October 2020. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- "Why can't WiFi work as full duplex while 3G and 4G can". community.meraki.com. 23 January 2020. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- "Bad Info Is Nothing New for WLAN- Don't Believe "Full Duplex" in Wi-Fi 6". Toolbox. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- "Federal Standard 1037C". Its.bldrdoc.gov. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- "American National Standard T1.523-2001, Telecom Glossary 2000". Atis.org. Archived from the original on 2 March 2008. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- "WiFi Frequency Bands List". Electronics Notes. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- IEEE 802.11-2016: Wireless LAN Medium Access Control (MAC) and Physical Layer (PHY) specifications. IEEE. 14 December 2016. doi:10.1109/IEEESTD.2016.7786995. ISBN 978-1-5044-3645-8.

- "802.11 WiFi Standards Explained". Lifewire. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- "Why Everything Wireless Is 2.4 GHz". WIRED. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- "802.11n Data Rates Dependability and scalability". Cisco. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- "3.1.1 Packet format" (PDF). IEEE Standard for Ethernet, 802.3-2012 – section one. 28 December 2012. p. 53. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 October 2014. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- Stobing, Chris (17 November 2015). "What Does WiFi Stand For and How Does Wifi Work?". GadgetReview. Archived from the original on 1 December 2015. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- Geier, Jim (6 December 2001). Overview of the IEEE 802.11 Standard. InformIT. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- US 5987011, Toh, Chai Keong, "Routing Method for Ad-Hoc Mobile Networks", published 16 November 1999

- "Mobile Computing Magazines and Print Publications". www.mobileinfo.com. Archived from the original on 26 April 2016. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- Toh, C.-K; Delwar, M.; Allen, D. (7 August 2002). "Evaluating the Communication Performance of an Ad Hoc Mobile Network". IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications. 1 (3): 402–414. doi:10.1109/TWC.2002.800539.

- Toh, C.-K; Chen, Richard; Delwar, Minar; Allen, Donald (2001). "Experimenting with an Ad Hoc Wireless Network on Campus: Insights & Experiences". ACM SIGMETRICS Performance Evaluation Review. 28 (3): 21–29. doi:10.1145/377616.377622.

- Subash (24 January 2011). "Wireless Home Networking with Virtual WiFi Hotspot". Techsansar. Archived from the original on 30 August 2011. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- Cox, John (14 October 2009). "Wi-Fi Direct allows device-to-device links". Network World. Archived from the original on 23 October 2009.

- "Wi-Fi gets personal: Groundbreaking Wi-Fi Direct launches today". Wi-Fi Alliance. 25 October 2010. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- "What is Wi-Fi Certified TDLS?". Wi-Fi Alliance. Archived from the original on 8 November 2014.

- Edney 2004, p. 8.

- Tjensvold, Jan Magne (18 September 2007). "Comparison of the IEEE 802.11, 802.15.1,802.15.4, and 802.15.6 wireless standards" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 July 2013. Retrieved 26 April 2013. section 1.2 (scope)

- "Somebody explain dBi – Wireless Networking – DSLReports Forums". DSL Reports. Archived from the original on 9 August 2014.

- "802.11n Delivers Better Range". Wi-Fi Planet. 31 May 2007. Archived from the original on 8 November 2015.

- Gold, Jon (29 June 2016). "802.11ac Wi-Fi head driving strong WLAN equipment sales". Network World. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- "WiFi Mapping Software:Footprint". Alyrica Networks. Archived from the original on 2 May 2009. Retrieved 27 April 2008.

- Kanellos, Michael (18 June 2007). "Ermanno Pietrosemoli has set a new record for the longest communication Wi-Fi link". Archived from the original on 21 March 2008. Retrieved 10 March 2008.

- Toulouse, Al (2 June 2006). "Wireless technology is irreplaceable for providing access in remote and scarcely populated regions". Association for Progressive Communications. Archived from the original on 2 February 2009. Retrieved 10 March 2008.

- Pietrosemoli, Ermanno (18 May 2007). "Long Distance WiFi Trial" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2008.

- Chakraborty, Sandip; Nandi, Sukumar; Chattopadhyay, Subhrendu (22 September 2015). "Alleviating Hidden and Exposed Nodes in High-Throughput Wireless Mesh Networks". IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications. 15 (2): 928–937. doi:10.1109/TWC.2015.2480398.

- Effect of adjacent-channel interference in IEEE 802.11 WLANs - Eduard Garcia Villegas, Elena Lopez-Aguilera, Rafael Vidal, Josep Paradells (2007) doi:10.1109/CROWNCOM.2007.4549783

- den Hartog, F., Raschella, A., Bouhafs, F., Kempker, P., Boltjes, B., & Seyedebrahimi, M. (2017, November). A Pathway to solving the Wi-Fi Tragedy of the Commons in apartment blocks. In 2017 27th International Telecommunication Networks and Applications Conference (ITNAC) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Caravan, Delia (12 September 2014). "6 Easy Steps To Protect Your Baby Monitor From Hackers". Baby Monitor Reviews HQ. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- Wilson, Tracy V. (17 April 2006). "How Municipal WiFi Works". HowStuffWorks. Archived from the original on 23 February 2008. Retrieved 12 March 2008.

- Brown, Bob (10 March 2016). "Wi-Fi hotspot blocking persists despite FCC crackdown". Network World. Archived from the original on 27 February 2019.

- "Towards Energy-Awareness in Managing Wireless LAN Applications". IEEE/IFIP NOMS 2012: IEEE/IFIP Network Operations and Management Symposium. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- "Application Level Energy and Performance Measurements in a Wireless LAN". The 2011 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Green Computing and Communications. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- Veendrick, Harry J. M. (2017). Nanometer CMOS ICs: From Basics to ASICs. Springer. p. 243. ISBN 9783319475974.

- "Free WiFi Analyzer-Best Channel Analyzer Apps For Wireless Networks". The Digital Worm. 8 June 2017. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017.

- "Apple.com Airport Utility Product Page". Apple, Inc. Archived from the original on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- "GainSpan low-power, embedded Wi-Fi". www.gainspan.com. Archived from the original on 30 June 2010. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- "Quatech Rolls Out Airborne Embedded 802.11 Radio for M2M Market". Archived from the original on 28 April 2008. Retrieved 29 April 2008.

- "CIE article on embedded Wi-Fi for M2M applications". Archived from the original on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- "Wifi Connectivity Explained | MAC Installations & Consulting". Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- Jensen, Joe (26 October 2007). "802.11 X Wireless Network in a Business Environment – Pros and Cons". Networkbits. Archived from the original on 5 March 2008. Retrieved 8 April 2008.

- Higgs, Larry (1 July 2013). "Free Wi-Fi? User beware: Open connections to Internet are full of security dangers, hackers, ID thieves". Asbury Park Press. Archived from the original on 2 July 2013.

- Gittleson, Kim (28 March 2014). "Data-stealing Snoopy drone unveiled at Black Hat". BBC News. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- Bernstein, Daniel J. (2002). "DNS forgery". Archived from the original on 27 July 2009. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

An attacker with access to your network can easily forge responses to your computer's DNS requests.

- Mateti, Prabhaker (2005). "Hacking Techniques in Wireless Networks". Dayton, Ohio: Wright State University Department of Computer Science and Engineering. Archived from the original on 5 March 2010. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- Hegerle, Blake; snax; Bruestle, Jeremy (17 August 2001). "Wireless Vulnerabilities & Exploits". wirelessve.org. Archived from the original on 19 September 2006. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- "WPA2 Security Now Mandatory for Wi-Fi CERTIFIED Products". Wi-Fi Alliance. 13 March 2006. Archived from the original on 25 August 2011.

- Vanhoef, Mathy (2017). "Key Reinstallation Attacks: Breaking WPA2 by forcing nonce reuse". Archived from the original on 22 October 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- Goodin, Dan (16 October 2017). "Serious flaw in WPA2 protocol lets attackers intercept passwords and much more". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 21 October 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 January 2012. Retrieved 1 January 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) US CERT Vulnerability Note VU#723755

- Federal Trade Commission (March 2014). "Tips for Using Public Wi-Fi Networks". Federal Trade Commission - Consumer Information. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- Thubron, Rob (9 January 2018). "WPA3 protocol will make public Wi-Fi hotspots a lot more secure". Techspot. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018.

- Kastrenakes, Jacob (26 June 2018). "Wi-Fi security is starting to get its biggest upgrade in over a decade". The Verge. Archived from the original on 20 February 2019. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- "NoCat's goal is to bring you Infinite Bandwidth Everywhere for Free". Nocat.net. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- Jones, Matt (24 June 2002). "Let's Warchalk" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 July 2008. Retrieved 9 October 2008.

- "Americans would give up TV before Internet: survey". GMA News Online. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- "The Digital Divide: A Survey of Information "Haves" and "Have Nots" in 1997". www.ntia.doc.gov. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- "Factors that Influence the Use of Computers". ininet.org. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- "Falling Through the Net: Toward Digital Inclusion | National Telecommunications and Information Administration". www.ntia.doc.gov. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- "A Nation Online". www.ntia.doc.gov. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- "A Nation Online: Entering the Broadband Age | National Telecommunications and Information Administration". www.ntia.doc.gov. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- "Free wifi may close the digital divide". BizEd. 2006.

- Dholakia, Ruby Roy (1 September 2006). "Gender and IT in the Household: Evolving Patterns of Internet Use in the United States". The Information Society. 22 (4): 231–240. doi:10.1080/01972240600791374. ISSN 0197-2243.

- "How Women and Men Use the Internet". Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. 28 December 2005. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- "Wireless Internet Access". Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. 25 February 2007. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- "Online world as important to internet users as real world?". Center for the Digital Future, Annenberg School for Communication, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA. 2007.

- Korupp, S.E. and Szydlik, M. (2005). "Causes and trends of the digital divide" (PDF). European Sociological Review. 21 (4): 409–423. doi:10.1093/esr/jci030.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Chaudhuri, A., Flamm, K.S. and Horrigan, J. (2005). "An analysis of the determinants of internet access". Telecommunications Policy. 29 (9–10): 731–755. doi:10.1016/j.telpol.2005.07.001.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Flamm, K. and Chaudhuri, A (2007). "An analysis of the determinants of broadband access". Telecommunications Policy. 31 (6–7): 321–326. doi:10.1016/j.telpol.2007.05.006.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Hprwire, editor. "The 51-Hour Day? Yahoo! Telemundo Research Shows Online U.S. Hispanics Consume and Adopt More Media and Technology than General Population | Hispanic PR Wire". Retrieved 8 May 2020.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Crockett, R.O. and Ante, S.E. (21 May 2007). "The internet: equal opportunity speedway". BusinessWeek: 44.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Marriott, Michel (31 March 2006). "Blacks turn to internet highway, and digital divide starts to close" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- Middleton, Karen L.; Chambers, Valrie (1 January 2010). "Approaching digital equity: is wifi the new leveler?". Information Technology & People. 23 (1): 4–22. doi:10.1108/09593841011022528. ISSN 0959-3845.

- Decker, Kris De (6 June 2017). "Comment bâtir un internet low tech". Techniques & Culture. Revue semestrielle d'anthropologie des techniques (in French) (67): 216–235. doi:10.4000/tc.8489. ISSN 0248-6016.