Washington, Baltimore and Annapolis Electric Railway

The Washington, Baltimore and Annapolis Electric Railway (WB&A) was an American railroad of central Maryland and Washington, D.C., built in the 19th and 20th century. The WB&A absorbed two older railroads, the Annapolis and Elk Ridge Railroad and the Baltimore & Annapolis Short Line, and added its own electric streetcar line between Baltimore and Washington. It was built by a group of Cleveland, Ohio, electric railway entrepreneurs to serve as a high-speed, showpiece line using the most advanced technology of the time.[1] It served Washington, Baltimore, and Annapolis, Maryland, for 27 years before the "Great Depression" and the rise of the automobile forced an end to passenger service during the economic pressures of the 1930s "Depression" southwest to Washington from Baltimore & west from Annapolis in 1935. Only the Baltimore & Annapolis portion between the state's largest city and its state capital continued to operate electric rail cars for another two decades, replaced by a bus service during the late 1950s into 1968. Today, parts of the right-of-way are used for the light rail line (from Cromwell Station / north Glen Burnie going north to downtown Baltimore and further north through city to Hunt Valley in Baltimore County), rail trail for hiking - biking trails, and roads through Anne Arundel County.

| |

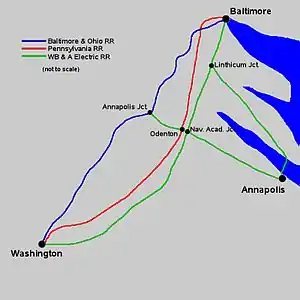

WB&A System map | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Annapolis, Maryland |

| Reporting mark | WB&A |

| Locale | Maryland and Washington, D.C. |

| Dates of operation | 1908–1935 |

| Successor | Franchise acquired by Baltimore-Washington Rapid Rail and the Northeast Maglev |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

History

Origins

The WB&A was originally incorporated in 1899 as The Potomac and Severn Electric Railway. On April 10, 1900, it changed its name to the Washington and Annapolis Electric Railway[2] and finally, on April 8, 1902, to the Washington, Baltimore and Annapolis Electric Railway.[3]

In 1903, the WB&A purchased the Annapolis, Washington & Baltimore Railroad (AW&B) — formerly the Annapolis & Elkridge Railroad — which was closed, electrified and reopened.[4] At the same time, it laid an almost straight double-track route parallel to the B&O and Pennsylvania railroads, but slightly to the east in less populated territory. On February 7, 1908, service began from Liberty Street in Baltimore to its Washington terminal at 15th and H Streets NE.[5] After 1910, the line reached the heart of downtown on 15th Street near the Treasury.[5] Another single track began at the B&O main line at Annapolis Junction, crossed the WB&A main line just east of Odenton, and headed east via Millersville and Crownsville to Annapolis.[1]

The line built by the WB&A, later called the Main Line, ran from Baltimore to Washington through Bowie, Glenn Dale Hospital, and Glenarden to Fairmont Heights where it met with the Chesapeake Beach Railway just outside Washington at Chesapeake Junction. From there, it continued to Deanwood on the Washington Railway and Electric Company's Seat Pleasant Line, running parallel to the Chesapeake Beach Railroad tracks and across the Benning Road Bridge into downtown Washington.

Once onto their own right-of-way, the WB&A's expresses regularly hit 60 mph, but street running in the terminal cities slowed their overall time. A typical B&O express made the trip in 50 minutes, but the best the WB&A could do was an hour and 20 minutes. Offsetting these handicaps were its cleanliness, lower fares, half-hourly express service, and better-located downtown terminals.[1]

Business Along the Route

Always looking for new sources of business, the railroad, in 1914, convinced the Southern Maryland Agricultural Fair Association to establish Bowie Race Track along the Main Line.[1]

In September 1917, as the U.S. entered World War I, George Bishop, the WB&A's well-connected president, persuaded the U.S. Army to acquire land owned by the railroad and open a training facility. Camp Meade was established in the area roughly bounded by the B&O Washington Branch on the west, the Pennsylvania Railroad on the east, and the South Shore Line of the WB&A to the south. The installation was supposed to be a temporary facility, used only for the duration of the war (it is still in use today). The WB&A saw record traffic during this time as a result of freight and passenger service to the camp. In 1918, the railroad was running as many as 84 special trains a day.[1]

Expansion

With the business seemingly successful, the WB&A purchased the Baltimore & Annapolis Short Line in 1921.[1] It became known as the "North Shore Line" and the Annapolis to Odenton line as the "South Shore Line". At this time, the B&A gave up its terminus at the Camden Street Station of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and started using the WB&A terminal on Liberty Street (between Lexington and Fayette) in Baltimore. Prior to 1921 the WB&A and B&A had run on separate, parallel tracks from Linthicum to Baltimore. But on March 16, 1921, a crossover connected the two parallel tracks at Linthicum operations ceased on the B. & O. track, and a new terminal was built at the southwest corner of South Howard and West Lombard Streets (current site after the early 1970s of Holiday Inn hotel) across from the Baltimore Civic Center (1st Mariner Arena).[7] The WB&A now consisted of 81 miles of track and the only practical way to get from Washington, D.C., to Annapolis.

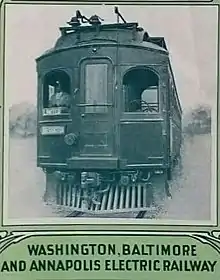

Equipment

Initial passenger equipment running from Baltimore-Washington to Annapolis was the "classic" 1900-1910 arch window all wood body truss rod frame interurban coach. In the 1920s when passenger business was good, the line purchased and operated steel two car articulated (attached body with a common center truck/boogie) coaches from Baltimore to Annapolis.[8][9] This equipment later went to the Milwaukee Electric Line in Wisconsin.[10]

Decline

Around the time of the purchase of the ASL, the Defense Highway was built providing an alternative route into Annapolis.[1] As a result, gross receipts for the railroad began to decline. The railroad only survived because of a law exempting it from taxes. In January 1931, during the Great Depression, the extension of the law failed to pass by one vote and the line went into receivership.[11] The line remained in operation for four more years and was eventually sold at auction in 1935. Evans Products Company of Detroit negotiated to buy the railroad in June 1935, but those negotiations failed and the railroad officially ceased operations on August 20, 1935.[12][13] Scrap dealers eventually bought most of the rolling stock. Evans bought the Arlington and Fairfax railroad the next year. Over time, the rails were hauled away, though by the beginning of World War II some remained and at least one post-War home in the area used old rails in lieu of I-beams. The right of way within Washington, D.C., remained under the ownership of WRECo and then the old Capital Transit Company.[14] At some point between 1951 and 1956, the tracks in D.C. were removed.[15]

The right of way of the North Shore Line and some equipment was bought by the Bondholders Protective Society, who then formed the Baltimore and Annapolis Railroad Company, which continued to operate rail passenger service between Baltimore and Annapolis until 1950 and freight service along with diesel passenger buses into the early 1970s to Brooklyn in South Baltimore, connecting with the #6 transit line for streetcars and buses of the old Baltimore Transit Company.

While the vast majority of the South Shore division was abandoned and sold for scrap in the 1930s, the portion between Annapolis Junction and Odenton was purchased and operated by the B&O to serve Fort Meade until sometime between 1979 and 1981. It too was removed. Only the junction tracks at Annapolis Junction, which are used by an aggregates terminal, and an abandoned spur to the old Nevamar plant in Odenton remain.

Accidents

On June 5, 1908, two of WB&A's single-car trains collided at Camp Parole, Maryland. Nine people died as a result of the crash, including Railroad Policeman J.G. Schriner.[16] The trains were ferrying riders to and from the United States Naval Academy for graduation ceremonies at the time of the accident.

Stations on the Main Line

- Baltimore

- Westport

- English Consul (Magnolia Avenue)

- Rosemont

- Baltimore Highlands (between Georgia and Illinois Avenues, across from the Baltimore and Annapolis Short Line Railroad station)

- Pumphrey

- North Linthicum

- Linthicum: Junction with North Shore Line

- Downs

- Wellham

- Kelly

- McPherson (WB&A Rd)

- Elmhurst

- Delmont

- Clark

- Severn Run

- Naval Academy: Junction with South Shore Line

- Waugh Chapel (Waugh Chapel Rd)

- Francis

- Bragers (Bragers Rd)

- Conway (Conway Rd)

- Meyers (Meyers Station Rd)

- Bowie

- Lloyd

- High Bridge

- Hillmeade

- Bell

- Randle

- Lincoln

- Vista

- Cherry Grove

- McCarthy

- Ardmore

- Glenarden

- Dodge Park

- East Columbia Park

- Huntsville

- Gregory

- District Line where the WB&A entered Washington, D.C., and the trains transferred to tracks interior to the city line.

- White House Station at 15th St and H St, NE

- 1st and H St, NE

- Treasury Building

Stations on the South Shore Line (Annapolis and Elk Ridge Railroad)

Stations on the North Shore Line (Baltimore and Annapolis Railroad)

Surviving landmarks

- The WB&A Terminal in Baltimore, now a former westside downtown Baltimore bank branch for the old Equitable Trust Company at North Liberty Street and Marion Street (alley)

- The Scott Street electric generating power substation on the NE corner of Scott and West Ostend Streets in southwest downtown

- The Westport tunnel's southern portal is visible just north of the Baltimore-Washington Parkway's Annapolis Road exit.

- The Baltimore Light Rail built in early 1990s uses the right-of-way twice: once from Baltimore Highlands through North Linthicum to a point north of Maple Road, and again from south of Linthicum to BWI Airport. The section of the Light Rail going to Glen Burnie (Cromwell Station) uses the Baltimore & Annapolis Railroad's parallel right-of-way.

- Linthicum railroad station [17]

- WB&A Boulevard in Severn was built on the right-of-way.

- A section of railroad track exists in the Academy Junction section of Odenton, Maryland. It branches off of Amtrak's Northeast Corridor just south of MD 175/Annapolis Road and travels east past the Odenton Library and across MD 170/Piney Orchard Parkway at grade before turning north to cross Annapolis Road, also at-grade. It then travels a short distance north to the site of the old Nevamar Company's manufacturing plant. That plant shut down in 2004 and trains haven't run on the spur since.

- At the northeast corner of the location where the track listed above crosses MD 170 (Telegraph Road) is a brick building that once housed the WB&A operations headquarters. The Baltimore-Washington main line and Fort Meade-Annapolis (South Shore) branch crossed at this location, known as "Naval Academy Junction." The interlocking tower that controlled this crossing comprised the second floor. Commercial office tenants occupy the building today.

- Parts of the Power line Path remains in use to this day. The single circuit 115KV path from WB&A Road (just south of BWI Airport) to Telegraph Road and Annapolis Road remains with some modifications. Another path was replaced by a double circuit 115KV monopole from Pumphrey to Linthicum. Both are now lines used by BGE.

- The "Naval Academy Junction" shops sat about one mile (1.6 km) north of "Naval Academy Junction," on the east side of MD 170. The brick shop buildings were subsumed into a larger building complex that housed a number of manufacturing companies, including Nevamar Plastics, but those shops were torn down in 2013. The electrical power plant for this section of the WB&A overhead still stands, and is visible from MD 170.

- Two portions of the WB&A Trail, one from Odenton Town Center to the Two Rivers development and another 5.8-mile (9.3 km) section from the Patuxent River to Glenn Dale, run on the old right-of-way of the Main Line. These two portions of the trail are not connected due, in part, to a property dispute that diverted the trail west in Anne Arundel County where a bridge will be built later.

- The trestle over Horsepen Branch on the Bowie Race Track spur, and short sections of roadbed on either side of the trestle. (A nearby rail trail signed "WB&A Spur Trail" branches off of the WB&A Trail and was built on a route that once served the race track, but the route was actually constructed subsequent to the WB&A's demise, by the Pennsylvania Railroad.).

- MD 704 was built on the right-of-way.

- BGE still has power lines in service on the former right of way in Prince George's County. Originally, they supplied power for the railway and when the railroad dissolved, they never gave it up. As a result, BGE still has a service area overlapping Pepco, the utility serving the Washington, DC metropolitan area.

- A freight motor, Washington Baltimore & Annapolis #1, is maintained at the Western Railway Museum in Rio Vista, California.

Acquisition

Baltimore-Washington Rapid Rail and the Northeast Maglev

In 2015, Baltimore-Washington Rapid Rail (BWRR) announced that the Maryland Public Service Commission (PSC) approved BWRR's application to acquire a passenger railroad franchise previously held by the Washington, Baltimore and Annapolis Electric Railroad Company. BWRR and the Northeast Maglev are working to deploy a Superconducting Maglev (SCMAGLEV) system that would connect Washington and Baltimore in 15 minutes.[18] The Northeast Maglev is currently working with the Federal Railroad Administration and Maryland Department of Transportation, the project sponsor, to prepare an Environmental Impact Statement for the proposed superconducting maglev system.[19]

References

- Herbert H. Harwood Jr. (2004–2005). "Washington, Baltimore & Annapolis Electric Railroad". Retrieved 2006-10-26.

- "Laws of the 1900 Maryland General Assembly Session". 1900. Retrieved 2006-10-23.

- "Laws of the 1902 Maryland General Assembly Session". 1902. Retrieved 2006-10-23.

- Herbert H. Harwood Jr. (2004–2005). "Annapolis & Elk Ridge Railroad". Retrieved 2006-10-12.

- Richard Layman (February 2003). "H St: A Neighborhood's Story Part II" (PDF). Retrieved 2006-12-11.

- National Trust Library Historic Postcard Collection, Special Collections, University of Maryland Libraries, circa 1912, http://digital.lib.umd.edu/image?pid=umd:90541

- Herbert H. Harwood Jr. (2004–2005). "Baltimore & Annapolis Railroad". Retrieved 2006-11-08.

- Harwood

- equipmet photographs: https://www.google.com/search?q=Baltimore+and+Annapolis+articulated+interurbans&rlz=1CASMAI_enUS760US760&tbm=isch&tbo=u&source=univ&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwi04pvdyO_bAhUpq1kKHUGsCp0QsAQIMw&biw=1366&bih=629

- ME photographs of articulated units http://www.thetransportco.com/id11.html

- "Williams v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, 289 U.S. 36 (1933)". March 1933. Retrieved 2006-10-23.

- "Washington Baltimore & Annapolis Electric Ry". Retrieved 2006-11-09.

- http://www.shorpy.com/node/17521

- "USGS 7.5 Minute Series map of Washington East, MD Quadrangle". 1945. Retrieved 2006-11-21.

- "US Geological Survey Maps". Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- "Railroad Policeman J. "George" G. Schriner, Washington, Baltimore & Annapolis Electric Railway Police Department, Railroad Police". 2011. Retrieved 2011-05-24.

- "Linthicum Station". Bull Sheet Monthly news. 2003. Retrieved 2009-09-25.

- Maglev, Baltimore Washington Rapid Rail; The Northeast. "Baltimore Washington Rapid Rail and The Northeast Maglev Announce Approval of Railroad Franchise Request by the Maryland Public Service Commission". www.prnewswire.com. Retrieved 2020-07-14.

- "Baltimore-Washington Superconducting Maglev Project | Permitting Dashboard". www.permits.performance.gov. Retrieved 2020-07-14.

- Merriken, John E. (1993). Every Hour On The Hour; A Chronicle of the Washington, Baltimore & Annapolis Electric Railroad. Taylor Publishing Company. ISBN 0-9600938-3-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Washington, Baltimore and Annapolis Electric Railway. |