Waterproof, Louisiana

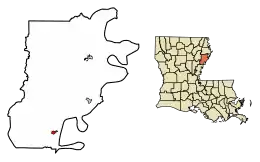

Waterproof is a village in Tensas Parish in northeastern Louisiana, United States with a population of 688 as of the 2010 census. The village in 2010 was 91.7 percent African American. Some 24 percent of Waterproof residents in 2010 were aged sixty or above.[3]

Waterproof, Louisiana | |

|---|---|

Village | |

| Village of Waterproof | |

Waterproof, Louisiana, Water Tower | |

| Motto(s): A Place You Can Call Home | |

Location of Waterproof in Tensas Parish, Louisiana. | |

.svg.png.webp) Location of Louisiana in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 31°48′25″N 91°23′07″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Louisiana |

| Parish | Tensas |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Jarrod Bottley (D) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 0.70 sq mi (1.81 km2) |

| • Land | 0.70 sq mi (1.81 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 69 ft (21 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 688 |

| • Estimate (2019)[2] | 555 |

| • Density | 796.27/sq mi (307.48/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| Area code(s) | 318 |

| FIPS code | 22-79940 |

Waterproof is approximately 17 mi (27 km) north of Ferriday, one of the two principal communities of Concordia Parish. The village is named for its relative safety from flooding prior to construction of the Mississippi River levee system.[4]

With a population dependent on agriculture, the rural village struggles with poverty. Mechanization has decreased the need for farm labor. Industrial-scale cotton is the major commodity crop, but corn and soybeans are also important. In 2008, drought destroyed much of the corn crop.

The former Hunter's Brothers Store, once a mainstay of Waterproof, is featured in an article in the first volume of the publication North Louisiana History.[5]

On December 8, 2018, the village elected its youngest mayor in history, Jarrod Randell Bottley, an African American male. He is 31 years old and serves the town on a full-time basis. In addition, he pastors multiple locations across the Mideast Louisiana region stretching from Concordia Parish to Tensas Parish to Ouachita Parish.

History

Civil War

During the American Civil War, a garrison of three hundred African-American Union troops (United States Colored Troops) based in Waterproof was attacked on February 13, 1864, by eight hundred Confederates under Captain Eli Bowman. The Federal gunboat Forest Rose opened fire from the Mississippi River and drove back Bowman's men. The next day Bowman resumed the attack, but the Forest Rose again shelled the Confederates, who again fell back in confusion. Joining Bowman was the cavalry commanded by Isaac F. Harrison. On February 15, Harrison, in command, tried to storm Waterproof but was again checked by the Forest Rose. Harrison was compelled to call off the attack and retreated westward toward Harrisonburg, the seat of Catahoula Parish. "The Confederates' unreasonable fear of gunboats had been insurmountable, and Waterproof remained in Federal hands," explained historian John D. Winters in his The Civil War in Louisiana (1963).[6]

20th century to present

Jim Crow rules were strong through the segregation era, and the Ku Klux Klan was active in southwest Louisiana through the late 20th century. Although there were 7,000 blacks living in the parish in 1964, none had been registered to vote. The 4,000 whites controlled parish and city politics for decades. The first 15 blacks were registered to vote in 1964, after passage of national civil rights legislation.[7]

Three young Waterproof men died in action in the Vietnam War: Carl Raymond Goodfellow, a navy ensign; Robert Lee Ross, an army private; and Douglas Mac Washington, an army sergeant.[8]

The village has the Tensas Parish Detention Center South. This prison facility holds inmates sentenced in Waterproof and Tensas County courts and courts of other cities in the Tensas Parish area. It has recently been used to detain undocumented immigrants. The listed address of Tensas Parish Detention Center South is 8606 Highway 65.

Case against mayor and police chief

In September 2006 Bobby D. Higginbotham was elected as mayor of Waterproof. After taking office, he hired Miles Jenkins as chief of police. Both native to Waterproof, the two African-American men had also lived and worked for years in other cities, including New Orleans. Jenkins had a 30-year career in the US military and earned a master's degree in public administration from Troy University in Alabama. He started to professionalize the small town police department.[7]

On July 24, 2007, Parish Sheriff Rickey A. Jones, who is white, arrested Higginbotham on counts of impersonating a police officer, criminal trespass, and felony criminal damage to property. Higginbotham claimed that Jones arrested him in order to prevent his running for sheriff again in the October 20, 2007, non-partisan blanket primary. Jones said he incurred $7,500 in legal fees before he took office as sheriff because Higginbotham sued him over allegations of a "rigged" election.[9] In the 2007 primary, Jones defeated Higginbotham, 2,188 votes (77.6 percent) to 631 votes (22.4 percent).[10]

Jones and District Attorney James E. Paxton of the Louisiana 6th Judicial District, who was elected in 2008, recognized Caldwell A. Flood, Jr., as the bona fide mayor of Waterproof. Police chief Miles Perkins was also arrested and charged for profiting from traffic tickets.[11]

In March 2010, Police Chief Miles Jenkins filed a lawsuit asserting conspiracy by Jones, Paxton, and other members of the white power structure to prevent the legal exercise of power by black elected officials. He said that he and Higginbotham were illegally forced from office and prosecuted by white officials. He cited numerous arrests by Jones and prosecution by Paxton, on charges that observers said they had never heard used against a police official. The case was closely watched by civil rights activists.[7]

Although the village is 55% black, Higginbotham was convicted by a jury of 11 whites and one black in 2010 of two charges: malfeasance in office and felony theft. He was sentenced to five years of hard labor, two years suspended, for malfeasance and seven years hard labor, three years suspended, for felony theft. The conviction was reversed and the sentence was vacated by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in April 2012, based on trial irregularities, including missing witness testimonies. Higginbotham had been freed on parole for good behavior in December 2011.[7] The Louisiana State Supreme Court denied a writ of certiorari. In 2016, the US Court of Appeals, Fifth Circuit, upheld the District Court decision denying habeas relief.[12]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1880 | 316 | — | |

| 1900 | 298 | — | |

| 1910 | 445 | 49.3% | |

| 1920 | 340 | −23.6% | |

| 1930 | 420 | 23.5% | |

| 1940 | 592 | 41.0% | |

| 1950 | 1,180 | 99.3% | |

| 1960 | 1,412 | 19.7% | |

| 1970 | 1,438 | 1.8% | |

| 1980 | 1,339 | −6.9% | |

| 1990 | 1,080 | −19.3% | |

| 2000 | 834 | −22.8% | |

| 2010 | 688 | −17.5% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 555 | [2] | −19.3% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[13] | |||

As of the census [14] of 2000, there were 834 people, 353 households, and 194 families residing in the town. The population density was 1,197.9 people per square mile (460.0/km2). There were 427 housing units at an average density of 613.3 per square mile (235.5/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 87.41% African American, 11.87% White, and 0.72% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.96% of the population.

In 2010, the African-American proportion of the declining, aged population was 91.7 percent.[3]

In 2000, there were 353 households, out of which 24.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 23.2% were married couples living together, 28.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 44.8% were non-families. 40.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 21.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.36 and the average family size was 3.30.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 28.8% under the age of 18, 8.2% from 18 to 24, 19.5% from 25 to 44, 25.2% from 45 to 64, and 18.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 41 years. For every 100 females, there were 75.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 66.9 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $10,250, and the median income for a family was $15,179. Males had a median income of $21,250 versus $14,792 for females. The per capita income for the town was $9,523. About 44.5% of families and 51.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 57.8% of those under age 18 and 57.6% of those age 65 or over.

Education

In 1935 and 1936, under coach and later Superintendent Statham Crosby, Waterproof High School competed for the state Class B football championship, losing to Vinton.[15]

Due to overall declining population and decreased student enrollment, Waterproof High School and Lisbon Elementary School were both closed under a Tensas Parish consolidation. Students now attend school in St. Joseph.

Two private schools in the parish, Tensas Academy in St. Joseph and Newellton Christian Academy, have mostly white students.

In popular culture

On March 4, 2000, Waterproof was featured on the National Public Radio talk show Whad'ya Know. The following is a partial transcription:

Back in the 1830s, one of the most popular spots for covered wagons crossing the Mississippi River was just north of present-day Natchez. As many as 50 wagons a day would cross, carrying settlers bound for Texas. Many of them tired of the journey, and simply stopped on the Louisiana side and made that spot home.

Often this area was under water, and on one such occasion, Abner Smalley, one of the early settlers, stood high and dry on a small strip of land waiting for a steamboat to make its usual landing for a refill of cordwood. The captain cried out to Mr. Smalley, "Well Abner, I see you're waterproof," and that's how the name of this town was born.

Present-day Waterproof is two and a half miles from its original location, having moved three times to escape flood waters. This led to the construction of a huge levee which snakes around the town, upon which you can walk and drive for a close view of the river.

Waterproof...is located in Tensas Parish. A variety of edible products is shipped from here including pecans, candies, pepper jellies and hams...along with the hunters' favorite 20-foot high deer hunting stands.

Notable people

- Sharon Renee Brown, Miss Louisiana USA 1961, Miss USA 1961 and Miss Waterproof in 1961; born in Waterproof.

- Claire Chennault (1893–1958), career officer and member of Flying Tigers, achieving the rank of general; born in Commerce, Texas, he was reared in Waterproof.

- Elliot D. Coleman, sheriff of Tensas Parish from 1936 to 1960, and a bodyguard serving Huey P. Long, Jr. when he was assassinated; born in Waterproof.

- Charles C. Cordill, planter and politician living near Waterproof; served as Louisiana state senator from 1884 to 1912; parish president and president of the police jury.[16]

- John Henry Johnson, professional football player and member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame; born in Waterproof.[17]

- Samuel W. Martien, major cotton planter and politician, serving as elected member of Louisiana House of Representatives from 1906 to 1920.[18]

- J. C. Seaman, state representative from 1944 to 1964; born in Waterproof.

- Johnny Weekly, professional baseball player; born in Waterproof in 1937.

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- 2010 U.S. census figures

- Hay, Jerry M. (2013). Mississippi River-Historic Sites & Interesting Places. Inland Waterways.

- W. Thomas Stewart, "Hunter's Brothers' Store: A Waterproof La. Landmark," North Louisiana History, Vol. 1, No. 4 (Summer 1970), pp. 20-24

- John D. Winters, The Civil War in Louisiana, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1963, ISBN 0-8071-0834-0, pp. 323-324

- Jordan Flaherty, "Conviction of Black Mayor Overturned by U.S. Court of Appeals in Case Closely Watched by Civil Rights Activists", Blog, Huffington Post, updated 25 June 2012; accessed 22 January 2018

- Tensas Parish: Military, Rootsweb

- "The News Star (Monroe, LA), 25 July 2007". Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- Louisiana Secretary of State-Parish Elections Inquiry

- "Jordan Flaherty, "Did a Racist Coup in a Northern Louisiana Town Overthrow Its Black Mayor and Police Chief?"". Dissident Voice. dissidentvoice.org. 26 March 2010. Retrieved June 12, 2010.

- Bobby D. HIGGINBOTHAM, Petitioner–Appellant v. State of LOUISIANA, Respondent–Appellee, No. 14–30753, 18 March ; FindLaw; accessed 22 January 2018

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "LHSAA Class B (1928-1969) Louisiana Football Championships". 222.14-0productions.com. Archived from the original on 2011-10-06. Retrieved August 8, 2011.

- Tensas Gazette, November 24, 1916

- Richard Goldstein (June 5, 2011). "John Henry Johnson Dies at 81; Inspired Fear on the Field". The New York Times.

- Obituary of Samuel Winter Martien, Tensas Gazette, 7 June 1946, p. 6

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Waterproof, Louisiana. |

- Waterproof Progress Community progress site for Waterproof