West Francia

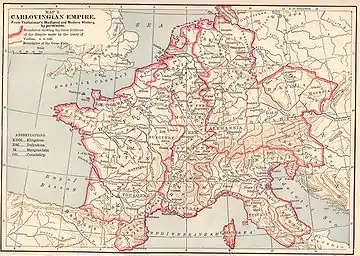

In medieval history, West Francia (Latin: Francia occidentalis) or the Kingdom of the West Franks (regnum Francorum occidentalium) refers to the western part of the Frankish Empire established by Charlemagne. It represents the earliest stage of the Kingdom of France, lasting from about 840 until 987. West Francia emerged out of the partition of the Carolingian Empire in 843 under the Treaty of Verdun following the death of Charlemagne's son, Louis the Pious.

Kingdom of the West Franks Francia occidentalis | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 843–987 | |||||||||||

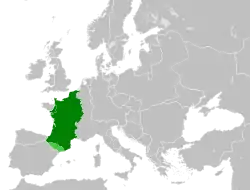

West Francia within Europe after the Treaty of Verdun in 843. | |||||||||||

| Capital | Paris | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Gallo-Roman, Latin, Frankish | ||||||||||

| Religion | Catholic Church | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||

• 840–877 | Charles the Bald (first) | ||||||||||

• 986–987 | Louis V of France | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||

| 843 | |||||||||||

| 870 | |||||||||||

• Capetian dynasty established | 987 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Denier | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||

West Francia extended further south than modern France, but it did not extend as far east. West Francia did not include such future French holdings as Lorraine, County and Kingdom of Burgundy (the Duchy being French), Alsace and Provence in the east and southeast for example. In addition, by the 10th century the rule of its kings was greatly reduced even within the West Frankish realm by the increase in power of great territorial magnates over their large and usually territorially contiguous fiefs. This process was compounded by wars among those magnates, including against or alongside the Crown, and endless Viking invasions. Notably, Normandy was given to the rule of the Norseman Rollo following an unsuccessful raid. It was first a county then a duchy, and like other great fiefs of West Francia became largely autonomous, with magnates even more powerful than their monarch. In Brittany and Catalonia the authority of the West Frankish king was barely felt. West Frankish kings were elected by the secular and ecclesiastic magnates, and for the half-century between 888 and 936 they chose alternately from the Carolingian and Robertian houses.[1] By this time the power of king became weaker and more nominal, as the regional dukes and nobles became more powerful in their semi-independent regions. The Robertians, after becoming counts of Paris and dukes of France, became kings themselves and established the Capetian dynasty after 987, which is, although arbitrary, generally defined as the gradual transition towards the Kingdom of France.

Formation and borders

In August 843, after three years of civil war following the death of Louis the Pious on 20 June 840, the Treaty of Verdun was signed by his three sons and heirs. The youngest, Charles the Bald, received western Francia. The contemporary West Frankish Annales Bertiniani describes Charles arriving at Verdun, "where the distribution of portions" took place. After describing the portions of his brothers, Lothair the Emperor (Middle Francia) and Louis the German (East Francia), he notes that "the rest as far as Spain they ceded to Charles".[2] The Annales Fuldenses of East Francia describe Charles as holding the western part after the kingdom was "divided in three".[3]

Since the death of King Pippin I of Aquitaine in December 838, his son had been recognised by the Aquitainian nobility as King Pippin II of Aquitaine, although the succession had not been recognised by the emperor. Charles the Bald was at war with Pippin II from the start of his reign in 840, and the Treaty of Verdun ignored the claimant and assigned Aquitaine to Charles.[4] Accordingly, in June 845, after several military defeats, Charles signed the Treaty of Benoît-sur-Loire and recognised his nephew's rule. This agreement lasted until 25 March 848, when the Aquitainian barons recognised Charles as their king. Thereafter Charles's armies had the upper hand, and by 849 had secured most of Aquitaine.[5] In May, Charles had himself crowned "King of the Franks and Aquitainians" in Orléans. Archbishop Wenilo of Sens officiated at the coronation, which included the first instance of royal unction in West Francia. The idea of anointing Charles may be owed to Archbishop Hincmar of Reims, who composed no less than four ordines describing appropriate liturgies for a royal consecration. By the time of the Synod of Quierzy (858), Hincmar was claiming that Charles was anointed to the entire West Frankish kingdom.[6] With the Treaty of Mersen in 870 the western part of Lotharingia was added to West Francia. In 875 Charles the Bald was crowned Emperor of Rome.

The last record in the Annales Bertiniani dates to 882, and so the only contemporary narrative source for the next eighteen years in West Francia is the Annales Vedastini. The next set of original annals from the West Frankish kingdom are those of Flodoard, who began his account with the year 919.[7]

Reign of Charles the Fat

After the death of Charles's grandson, Carloman II, on 12 December 884, the West Frankish nobles elected his uncle, Charles the Fat, already king in East Francia and Kingdom of Italy, as their king. He was probably crowned "King in Gaul" (rex in Gallia) on 20 May 885 at Grand.[8] His reign was the only time after the death of Louis the Pious that all of Francia would be re-united under one ruler. In his capacity as king of West Francia, he seems to have granted the royal title and perhaps regalia to the semi-independent ruler of Brittany, Alan I.[9] His handling of the Viking siege of Paris in 885–86 greatly reduced his prestige. In November 887 his nephew, Arnulf of Carinthia revolted and assumed the title as King of the East Franks. Charles retired and soon died on 13 January 888.

In Aquitaine, Duke Ranulf II may have had himself recognised as king, but he only lived another two years.[10] Although Aquitaine did not become a separate kingdom, it was largely outside the control of the West Frankish kings.[1]

Odo, Count of Paris was then elected by nobles as the new king of West Francia, and was crowned the next month. At this point, West Francia was composed of Neustria in the west and in the east by Francia proper, the region between the Meuse and the Seine.

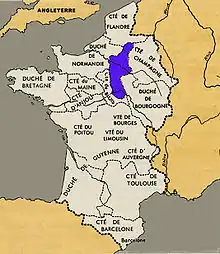

Rise of Robertians

After the 860s, Lotharingian noble Robert the Strong became increasingly powerful as count of Anjou, Touraine and Maine. Robert's brother Hugh, abbot of Saint-Denis, was given control over Austrasia by Charles the Bald. Robert's son Odo was elected king in 888.[11] Odo's brother Robert I ruled between 922 and 923 and was followed by Rudolph from 923 until 936. Hugh the Great, son of Robert I, was elevated to the title "duke of the Franks" by king Louis IV. In 987 his son Hugh Capet was elected king and the Capetian dynasty began. At this point they controlled very little beyond the Île-de-France.

Rise of dukes

Outside the old Frankish territories and in the south local nobles were semi-independent after 887 as duchies were created: Burgundy, Aquitaine, Brittany, Gascony, Normandy, Champagne and the County of Flanders.

The power of the kings continued to decline, together with their inability to resist the Vikings and to oppose the rise of regional nobles who were no longer appointed by the king but became hereditary local dukes. In 877 Boso of Provence, brother-in-law of Charles the Bald, crowned himself as the king of Burgundy and Provence. His son Louis the Blind was king of Provence from 890 and Emperor between 901 and 905. Rudolph II of Burgundy established the Kingdom of Arles in 933.

Charles the Simple

After the death of East Francia's last Carolingian king Louis the Child, Lotharingia switched allegiance to the king of West Francia, Charles the Simple. After 911 the Duchy of Swabia extended westwards and added lands of Alsace. Baldwin II of Flanders became increasingly powerful after the Odo's death in 898, gaining Boulogne and Ternois from Charles. The territory over which the king exercised actual control shrank considerably, and was reduced to lands between Normandy and river Loire. The royal court usually stayed in Rheims or Laon.[12]

Norsemen began settling in Normandy, and from 919 Magyars invaded repeatedly. In the absence of strong royal power, invaders were engaged and defeated by local nobles, like Richard of Burgundy and Robert of Neustria, who defeated Viking leader Rollo in 911 at Chartres. The Norman threat was eventually ended, with the last Danegeld paid in 924 and 926. Both nobles became increasingly opposed to Charles, and in 922 deposed him and elected Robert I as the new king. After Robert's death in 923 nobles elected Rudolf as king, and kept Charles imprisoned until his death in 929. After the rule of king Charles the Simple, local dukes began issuing their own currency.

Rudolf

King Rudolf was supported by his brother Hugh the Black and son of Robert I, Hugh the Great. Dukes of Normandy refused to recognise Rudolf until 933. The King also had to move with his army against the southern nobles to receive their homage and loyalty, however, the count of Barcelona managed to avoid this completely.

After 925 Rudolf was involved in a war against the rebellious Herbert II, Count of Vermandois, who received support from kings Henry the Fowler and Otto I of East Francia. His rebellion continued until his death in 943.

Louis IV

King Louis IV and Duke Hugh the Great were married to sisters of East Frankish king Otto I who after the deaths of their husbands managed Carolingian and Robertine rule together with their brother Bruno the Great, archbishop of Cologne, as regent.

After further victories by Herbert II, Louis was rescued only with the help of the large nobles and Otto I. In 942 Louis gave up Lotharingia to Otto I.

Succession conflict in Normandy led to a new war in which Louis was betrayed by Hugh the Great and captured by Danish prince Harald who eventually released him to the custody of Hugh, who freed the king only after receiving town of Laon as a compensation.[13]

Lothair

The 13-year old Lothair of France inherited all the lands of his father in 954. By this time they were so small that the Carolingian practice of dividing lands among the sons was not followed and his brother Charles received nothing. In 966 Lothair married Emma, stepdaughter of his grandfather Otto I. Despite this, in August 978 Lothair attacked the old imperial capital Aachen. Otto II retaliated by attacking Paris, but was defeated by the combined forces of king Lothar and nobles and peace was signed in 980.

Lothar managed to increase his power, but this was reversed with the coming of age of Hugh Capet, who began forming new alliances of nobles and eventually was elected as king.

List of kings

- Charles the Bald (843–877)

- Louis the Stammerer (877–879)

- Louis III of France (879–882)

- Carloman II (882–884)

- Charles the Fat (885–888)

- Odo of France (888–898)

- Charles the Simple (898–922)

- Robert I of France (922–923)

- Rudolph of France (923–936)

- Louis IV of France (936–954)

- Lothair of France (954–986)

- Louis V of France (986–987)

- Hugh Capet (987–996)

Notes

- Lewis 1965, 179–180.

- AB a. 843: ubi distributis portionibus ... cetera usque ad Hispaniam Carolo cesserunt.

- AF a. 843: in tres partes diviso ... Karolus vero occidentalem tenuit.

- AF a. 843: Karolus Aquitaniam, quasi ad partem regni sui iure pertinentem, affectans ... ("Charles wanted Aquitaine, which belonged by right to a part of his kingdom").

- Coupland 1989, 200–202.

- Nelson 1977, 137–38.

- Koziol 2006, 357.

- MacLean 2003, 127.

- Smith 1992, 192.

- Richard 1903, 37–38.

- The Cambridge Illustrated History of France

- The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 3, C.900-c.1024

- The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 3, C.900-c.1024

References

- Jim Bradbury. The Capetians: Kings of France, 987–1328. London: Hambledon Continuum, 2007.

- Simon Coupland. "The Coinages of Pippin I and II of Aquitaine" Revue numismatique, 6th series, 31 (1989), 194–222.

- Geoffrey Koziol. "Charles the Simple, Robert of Neustria, and the vexilla of Saint-Denis". Early Medieval Europe 14:4 (2006), 355–90.

- Archibald R. Lewis. The Development of Southern French and Catalan Society, 718–1050. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1965.

- Simon MacLean. Kingship and Politics in the Late Ninth Century: Charles the Fat and the end of the Carolingian Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Janet L. Nelson. "Kingship, Law and Liturgy in the Political Thought of Hincmar of Rheims". English Historical Review 92 (1977), 241–79. Reprinted in Politics and Ritual in Early Medieval Europe (London: Hambledon, 1986), 133–72.

- Alfred Richard. Histoire des Comtes de Poitou, vol. 1 Paris: Alphonse Picard, 1903.

- Julia M. H. Smith. Province and Empire: Brittany and the Carolingians. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.