Duchy of Gascony

The Duchy of Gascony or Duchy of Vasconia (Basque: Baskoniako dukerria; Occitan: ducat de Gasconha; French: duché de Gascogne, duché de Vasconie) was a duchy in present southwestern France and northeastern Spain, an area encompassing the modern region of Gascony. The Duchy of Gascony, then known as Wasconia, was originally a Frankish march formed to hold sway over the Basques (Vascones). However, the Duchy went through different periods, from its early years with its distinctively Basque element to the merger in personal union with the Duchy of Aquitaine to the later period as a dependency of the Plantagenet kings of England.

Duchy of Gascony / Duchy of Vasconia | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 602–1453 | |||||||||

Coat of arms

| |||||||||

The duchy of Gascony / Vasconia (green) in 1150 | |||||||||

| Capital | Bordèu | ||||||||

| Common languages | Gascon Basque Middle Latin | ||||||||

| Religion | Catholic Christianity Basque paganism | ||||||||

| Duke of Gascony / Duchy of Vasconia[1] | |||||||||

• 602 | Genial | ||||||||

• 1009 | Sancho VI William of Gascony | ||||||||

• 1052 | William VIII, Duke of Aquitaine | ||||||||

• 1362 | Edward the Black Prince | ||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||

• Duke appointed by the Frankish kings | 602 | ||||||||

• Annexed by the Kingdom of France | 1453 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

In the Hundred Years' War, Charles V of France conquered most of Gascony by 1380, and under Charles VII of France it was incorporated into the kingdom of France in its entirety in 1453. The corresponding portion within Spain became part of the Basque Kingdom of Navarre.

History

Formation

Gascony was the core territory of Roman Gallia Aquitania. This province, by the 2nd century, was extended to include much of western Roman Gaul, as far north as the Loire. Thus, the name of the Aquitani came to be transferred to the territory of central-western France later known as the Duchy of Aquitaine. In 293, Diocletian re-created the original province of Caesar's Aquitania under the name of Novempopulania or Aquitania Tertia.

The Vascones were a people of the southwestern Pyrenees in the Roman period, but by the end of the 6th century, the Vascones defined a confederacy of native tribes with similar language and traditions on both sides of the Pyrenees who had not been culturally Romanized. Around 580, both the Visigothic kingdom and the kingdom of the Franks launched major campaigns against the Basques. In 587 Basques are cited as raiding the plains of Aquitaine, maybe to the west of Toulouse. Chilperic I sent his duke Bladastes stationed in Toulouse, but was defeated. After taking the throne, Leovigild launched a series of military campaigns around the Iberian Peninsula, taking control from the Basques ("partes Vasconiae") in the upper reaches of the Ebro (present-day Álava, possibly up to the north of Castile), and founded a fortress called Victoriacum (dubiously Vitoria-Gasteiz, possibly Iruña-Veleia).

This military push from a stronger centralized authority in Toledo placed more pressure on the Basques to get off the Ebro rich farmland than those already stretching all the way to the Garonne. In this period (585), the count of Bordeaux Galactorius is cited as fighting the Basques, who are portrayed as hiding out in the mountains, and the Cantabrians.

Early Frankish period (602–660)

In 602, the Merovingians created a frontier duchy to their southwest during the tripartite wars between Franks, Visigoths, and Basques. A certain Genial was then appointed dux wasconum as a way of better handling their relations with the Basques. At the same time, the Visigoths created the Duchy of Cantabria as a buffer against the Basques inhabiting west of current Navarre. The march of Vasconia (or Wasconia) was created with the purpose of controlling the Basques in Novempopulania, but it extended at this stage on the lands south and around the axis provided by the river Garonne between Bordeaux and Toulouse. About this period duke Francio is reported to vow allegiance to the Franks in Cantabria, an area inhabited by the Basques, but c. 612, the Gothic king Sisebut seems to have conquered the territory.

By the year 602, the duchy of Vasconia, under Frankish overlordship, was consolidated in the areas around the Garonne river but it may have extended up to Cantabria, under Frankish domain at the time of and before the creation of the Duchy.[2]:23–50 In the years 610 and 612 respectively, the Gothic kings Gundemar and Sisebut launched attacks against the Basques. After a Basque attack in the Ebro valley in the year 621, Swinthila defeated them and founded the fortress of Olite.

In 626, the Basques rebelled against the Franks, with the bishop of Eauze being exiled on the accusation of supporting or sympathising with the Basque rebels,[3] while in 635 a gigantic Frankish expedition led by the duke Arnebert and 9 more dukes launched an attack against the Basques, forcing them to retreat to the mountains, while Arnebert's column was defeated in Subola, maybe near Tardets. However, the Basques' relish was short-lived since they were brought to heel by Dagobert (Clichy, 636).[4]:96 By 626, it is certain that the duchy extended up to the Pyrenees and Vasconia had replaced Novempopulania as a preferred name for the geographical area between the Pyrenees and the Garonne. In 643, there was another rebellion to the north of the Pyrenees and in 642 and 654 they battled against the Visigoths to the south, in Saragossa.[4]:97 From 589 to 684, the Bishop of Pamplona was absent from the Visigothic Councils of Toledo, which is interpreted by some as the result of this city being under Basque or Frankish control.

Personal union with Aquitaine (660–769)

.jpg.webp)

In the year 660, Felix of Aquitaine, a patrician from Toulouse of Gallo-Roman stock, received the ducal title of both Vasconia and Aquitaine (located between the Garonne and Loire rivers), effectively ruling independently over Vasconia and at least part of Aquitaine. Under Felix and his successors, Frankish overlordship over these lands became merely nominal, and Vasconia became a prominent regional power. The Ravena Cosmography cites "Wasconia" as extending up to the Loire, although the real concept behind the name is contested; it further divides the territory into Guasconia (north of Garonne) and Spanoguasconia (south of Garonne).

Independent dukes Lupus, Odo, Hunald and Waifer succeeded him respectively, with the last three belonging to the same lineage. Their ethnicity is not certain, since records and their names are not conclusive.

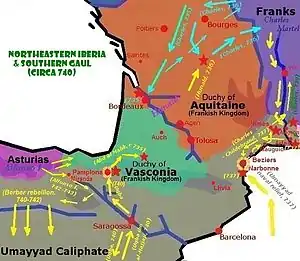

But the Umayyad invasion of 711 effected a complete shift in trends. Hitherto the duke Odo the Great had been independent, refusing to recognise the authority of either the Merovingian king or his mayor of the palace. In 714, Pamplona was captured by the Umayyads. In 721, Odo defeated the Arabian-African forces at the Battle of Toulouse.[5] :21 However, in 732 he was utterly routed at the Battle of the River Garonne near Bordeaux, after which the Muslim troops under Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi plundered the country and captured Narbonne. Only by submitting to the suzerainty of his Frankish archrival, the mayor Charles Martel, could they decisively defeat the Umayyad invaders at the Battle of Tours. Aquitaine and its attendant marches were then united to Francia, but Odo probably kept ruling the Duchy of Vasconia and Aquitaine about the same as before until his death.[5]:22

Odo died c. 735, leaving his realm to his son Hunald, who desiring the former independence which had been his father's, attacked Martel's successors, starting a war which was to last for two generations. In 743, the situation was further complicated by the arrival of Asturian forces attacking Vasconia from the west. In 744, Hunald abdicated to his son Waifer, who repeatedly challenged Frankish overlordship. After a campaign against the Umayyads in Septimania, the king Pepin the Short turned his attention to Aquitaine and Waifer, unleashing a devastating war on Aquitaine (Vasconia included) that was to have dire consequences on its population, towns and society.[5]:27 Waifer and his Basque troops confronted Pepin several times but were defeated thrice in 760, 762, and 766, after which Aquitaine and Vasconia pledged loyalty to Pepin and Waifer was eventually murdered by desperate followers, or possibly by someone bribed by Pepin.

Carolingian duchy (769–864)

Beginning in 778, Charlemagne did appoint counts (Bordeaux, Toulouse, Fezensac) on the bordering lands of Vasconia along the banks of the river Garonne, so undermining the influence of the dukes of Vasconia.

The Basques however found a pivotal ally in the south in the Basque Muslim realm of the Banu Qasi (early 9th century), and enjoyed some safety from the west, as the Asturians were immersed in continuous dynastic conflicts. The time of Charlemagne's reign was rife with conflicts between Basques, Franks and Muslims. Most famous is the Battle of Roncevaux in 778, during which Basques ambushed and slaughtered Charlemagne's rearguard after the Franks destroyed the walls of Pamplona. Heavily mythologised from the 11th century on as a clash between Christians and Muslims, this battle became one of the most celebrated events in the legendary Matter of France.

Muslims attacked Vasconia as well, taking possession of Pamplona for some time, but they were expelled by a rebellion in 798-801 that helped to create the Basque Muslim realm of the Banu Qasi around Tudela. In 806 Pamplona, still under Cordovan rule, was attacked by the Franks; and the Pamplonese, led by a certain Velasco, pledged allegiance to Charlemagne again, but his tenure proved short lived. At about 814, an anti-Frankish faction led by Enecco, allied with the Banu Qasi, seems to have taken over again. A Frankish army was sent to quash the revolt, to little effect. Furthermore, on their way north through Roncevaux an ambush was attempted, but resulted in a stalemate as the Franks had taken Basque women and children hostage.

Northern Basques, organized in the Duchy of Vasconia, collaborated with Franks during campaigns such as the capture of Barcelona in 799 but after the death of Charlemagne in 814, uprisings started anew. The revolt in Pamplona crossed the Pyrenees north and in 816 Louis the Pious deposed the Basque Duke Seguin of Bordeaux for failing to suppress or sympathising with the rebellion, so starting a widespread revolt, led by García Jiménez (according to late traditions, a near-kinsman of Íñigo Arista, to be the first monarch of Pamplona) and newly appointed duke Lupus Centullo (c. 820). Meanwhile, in Aragon the pro-Frankish Count Aznar Galindo was overthrown by Enecco's allied Count Gartzia Malo, with Aznar Galindo in turn seeking refuge in Frankish-held territory. Louis the Pious received the submission of rebel Basque lords in Dax, but things were far from settled.

In 824 the second Battle of Roncevaux took place, when counts Eblo and Aznar Galindo (identified as Aznar Sánchez too), Frankish vassals and the latter appointed Duke of Gascony, were captured by the joint Pamplonese and Banu Qasi forces, strengthening the independence of Pamplona. In the early 9th century the lands around the Adour river were segregated from the Duchy under the name of County of Vasconia. Count Aznar's successor, Sans Sancion, fought against Charles the Bald, as Charles didn't recognize him as legitimate.

In 844, Vikings invaded Bordeaux and killed Duke Seguin II. His heir William was killed trying to retake Bordeaux in 848,[6] though some sources say he was only captured and later deposed by the king. By the year 853, Sans Sancion, the Basque leader, was recognised as duke by Charles the Bald. During that same year, Muza of Tudela, relative of the Basque princes, invaded Vasconia and made Sans prisoner. In 855, Sans died and was succeeded by Arnold, who died fighting against the Norse in 864.

Basque duchy of Gascony (864–1053)

Sancho III Mitarra (or Menditarra, cited in 864) appears to be the founder of a lineage of autochthonous independent dukes ruling Gascony up to Sancho VI William (died in 1032), with loose ties, if any, to the Frankish Kingdom.[4]:137

The dukes had to face Viking inroads and unrest for over a century, an instability that brought about the destruction of existing monasteries in Gascony and a decayed urban life. The dukes of Gascony faced up against the Norsemen (Vikings), and a king of Navarre is cited as providing assistance against them near Bayonne. The Gascon ducal family became tied to the rising Kingdom of Navarre by matrimonial alliances at the end of the 10th century, eventually bringing Gascony suzerain to King Sancho III of Navarre ("the Great") for a short period up to 1035.[4]:181–182

While the gradual decay of the Carolingian dynasty would have been expected to pave the way for a reassertion of its regional identity, new borders, a more rigid structure derived from feudalizalization, and internal Basque divergences of culture, interest and language stopped that process.[4]:179 Dukes parcelled out the duchy as appanages for their sons — the power of decision was gradually transferred in the 9th and 10th centuries to Gascony's smaller constituent counties, such as Béarn, Armagnac, Bigorre, Comminges, Nébouzan, Labourd, etc.

The Duchy of Vasconia between the Adour and the Garonne, gradually became the Duchy of Gascony, moving away from the history of the Basque Country as Gascon (a romance language) took hold in 'greater Gascony', so stripping the name of its former ethnic connotations and lending it a political one. By the 11th-12th century, Basque language is believed to extend on the north-east up to the upper reaches of the Adour river, far short of its extension 300 years before.[4]:112

Within the Duchy of Aquitaine (1053–1453)

After Sancho the Great's reign, Gascony distanced again from Pamplona. By 1053, Gascony was inherited and conquered by the Duchy of Aquitania. It thus became a part of the Angevin Empire in the 12th century. The ducal title was reemployed by Edward Longshanks and it formed a base of support for the English during the Hundred Years' War. Margaret Wade Labarge called it England's first foreign colony.[7]

England lost Gascony as a result of its defeat in the Hundred Years' War, and the region thence became a permanent part of France.

Feudal status

Under the Basque line of dukes that began in 864, Gascony became effectively independent of the Frankish kings. In 1004, Abbo of Fleury, when visiting the monastery of La Réole, claimed to be more powerful there than the king, since nobody recognised his power. Charters of La Réole are dated by the reign of the duke of Gascony and not that of the king of France. Nonetheless, charters from elsewhere in Gascony continued to be dated by the reigns of the Frankish kings down to the acquisition of Gascony by Aquitaine.[8]

According to the cartulary of Saint-Seurin at Bordeaux in 1009, "the custom is that no count [of Gascony] can legitimately govern in this city of Bordeaux if he has not received the charge of the consulate, eyes lowered, from the most holy saint bishop Seurin and if he does not make an annual tribute." A later notice from between 1160 and 1180, says specifically that the would-be count must lay his sword on Saint Seurin's altar and then only take it up again after receiving the saint's standard. These practices parallel the practice of the French kings of receiving their kingdom from Saint Denis and carrying his banner, the Oriflamme. It is possible, however, that the notices in the cartulary of Saint-Seurin, which both elevate that religious house and at the same time distance the dukes of Gascony from any French vassalage, were forged in the late 12th century to advance the cause of the Plantagenets.[9]

Extent during the Early Frankish period

Frankish Wasconia comprised the former Roman province of Novempopulania and, at least in some periods, also the lands south of the Pyrenees centred on Pamplona.[10] It follows that the Duchy of Vasconia comprised Basque areas north and south of the Pyrenees at least until the definite detachment of Pamplona from the Duchy in 824.

In 628 the Frankish king Dagobert I made arrangements for his brother Charibert II to rule over the territories between the Loire and the Pyrenees (limes Spaniae) 'in the general area of Vasconia', including Saintes, Perigueux, Cahors, Agenais, etc.[11]:94–96 In the following years, the same king is reported to have subjugated the whole of Vasconia, meaning that it extended beyond the Pyrenees as well.

The Ravenna Cosmographer refers to Vasconia as the whole territory stretching out to the Loire, and so does the Chronicle of Fredegar, suggesting that it lies south of the Loire.[4]:96 but the nature of this naming is subject to debate. At any rate, Basques on either side of the Garonne are cited in the last independent years of the Duchy up to 768, but this year, its northern boundary was pinpointed on the river Garonne. Several authors have put down this large geographical extent of the 7th-8th centuries to an expansion of the Basques from their assumed original habitations around the Pyrenees.

Social organisation during the Early Frankish period

Unlike neighbouring regions, counts did not play a role in Vasconia's power share. Moreover, they were absent, and dukes are mentioned as the main figures of the Basques, immediately followed on the hierarchy by tribal chiefs and families, at least until the rise of the Carolingian dynasty.[5]:7–8As for the judicial system, neither the Visigoth law nor Roman law seem to have been in use in the Duchy of Vasconia,[5]:8 and a native order may have prevailed at least until the Carolingian takeover in 768-769.

As of 778, Charlemagne started appointing counts (Bordeaux, Toulouse, Fezensac) on the bordering lands of Vasconia along the banks of the river Garonne, so undermining the grip on power of the dukes of Vasconia.

Dukes and counts of Vasconia

The names of the dukes are recorded under a bewildering number of variants, which makes identification very difficult. These dukes and counts were leaders of the Basque clans that dominated Gascony and so their native names were Basque. However, as the Gascon language gradually replaced Basque, their names are also recorded in Gascon. Indeed, eventually the dukes of Gascony probably themselves adopted Gascon, which is reflected in the declining use of authentically Basque names by the last dukes.

In written documents, their names were usually recorded in Latin, which was the favored written language at the time. Today, their names are also frequently found in their French version, and also sometimes in their Spanish version. One example: the Basque name Otsoa (meaning "wolf") was literally translated Lop in Gascon, Lupus in Latin, Loup in French, and Lobo in Spanish. Thus, Duke Otsoa II of Gascony can be known by any of these names, which confuses people not used to the local linguistic situation. Furthermore, even within a set language, there exist many different written variants, as for the Basque name Santso (from Latin sanctus, meaning "holy"), which can be found in Basque documents written Antso, Sanzio, Santio, Sanxo, Sancio, and so on.

Usually, the dukes and counts of Gascony had two names, the first one being their given name, the second one being the given name of their father (for example, Duke Sans I Lop, which means this is Duke Sans I, son of Lop). This custom later generated the Spanish family names, with the adding of suffix -ez meaning "son of". "Juan Sánchez" literally means "John, son of Sancho". For a few dukes of Gascony, the second name is not the given name of their father, but it is a nickname that they gained over time and that replaced the given name of their father, such as the famous duke Sans III Mitarra, where Mitarra is not the name of his father, but a nickname referring to his origin, probably "Menditarra",[4]:173 with a typical Basque -tarra suffix to express origin.

There is one duke of Gascony subject to a historiographical discussion, and that is Duke Seguin I (Segiwin, Sihimin,...). It has been contended that it actually hides a Basque "Semen"—written forms Semeno, Xemen, Ximen, or Jimeno. It may be that native Basque name based on the word seme (meaning "son", attested in Aquitanian engravings), or it may be "Seguin" (modern Gascon "Siguin"), a name of Germanic origin based on sig, meaning 'victory' (cf modern German Sieg), and win, meaning 'friend'.

It has been suggested that some apparently Basque names are merely corruptions of late Germanic names. For example, Garsinde leading to Garsean, Gendolf or Centulf to Centule, Aginald or Hunnald to Enneko (in Flanders, and Frisian, still a short form of the first two frank names), Aginard to Aznar, Belasgytta or Wallagotha to Velasquita, Belasgutho to Velasco, Arnoald to Arnau, Theuda to Toda, Theudahilda to Dadildis or Dedadils. While some of them may be so, many of them—Andregoto, Amunna, Aznar(i), Velasco, Garcia, Ximen(o), Enneco—have well explained forms according to consistent linguistic rules and etymologies, as described by linguist Koldo Mitxelena. The oldest Basque medieval names reflected totemic (animal) references,[12]:37 and family links.

In the list below, the dukes and counts of Gascony are listed according to their Gascon names (based on the current spelling of Gascon, not the medieval spelling, which was fluctuating).

Frankish and native dukes

- Genial (602-626)

- Aeghyna (626-638)

- Felix (660s)

- Lupus I (670-676 or possibly until 710 in Vasconia only[13])

- Odo the Great (or Eudes) (688-735), his reign commenced perhaps as late as 692, 700, 710 or 715, unclear parentage.

- Hunald I (735-748), son of previous, abdicated to monastery, may have returned later (see below).

- Waifer (or Gaifier) (748-767), son of previous.

- Hunald II (767-769), either Hunald I returning or a different Hunald, fled to Lupus II of Gascony and was handed over to Charlemagne.

House of Gascony

| Ruler | Dates | Consort | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lop II | 768/70-778/801 | Numabela of Cantabria five children | Probably the founder of a Gascon line of dukes. | ||

| Sans I Lop | 778/801-812 | Unknown five children | Son of the predecessor. | ||

| Seguin I Lop | 812-816 | Unknown one child | Brother of the predecessor, rebelled against the Franks. | ||

| Gassia I Semen | 816-818 | Unknown | Son of the predecessor. Rebelled against the Franks. | ||

| Lop III Centullo Wasco | 818-819/23[13] | Unknown two children | Son of the predecessor, or of Centullo, brother of Sans I. Rebelled against the Franks. | ||

After Lop Centullo's death the duchy was divided: the County of Vasconia temporarily segregated from the Duchy. See: Northern Basque Country.

In 852, Sans II, from the rebel county, eventually reunited Gascony and regained the ducal title. | |||||

| Sans II Sancion | 852-855/64 | Unmarried | Son of Aznar Sans, and the new duke from 852. | ||

| Arnaut | 855/64[13] | Son of Sansa Sancion, daughter of Sans I. | |||

| Sans III Sancion the Terrible (Sans Mitarra) | 864-893 | Unknown one child | Son of Sans II. | ||

| Gassia II Sans the Bent (Gassia Okerra) | 893-930 | Amuna of Angoulême c.875 six children | Son of the predecessor. | ||

| Sans IV Gassia | 930-c.950 | Unknown two children Unknown five children | Son of the predecessor. | ||

| Sans V Sancion | c.950-961 | Unmarried | Son of Sans II. Some historians believe his name was instead Gassia.[14] | ||

| Guilhem II Sans | c.961-996 | Urraca Garcés of Navarre c.972 one child | Brother of the predecessor. Might have been him who fought the Vikings in Galicia, in 970. | ||

| Bernat I Guilhem | 996-1009 | Unmarried | Son of the predecessor. | ||

| Sans VI Guilhem | 1009-1032 | Brother of the predecessor. | |||

House of Poitiers

- Eudes (1032–1039)

House of Armagnac

- Bernat II (1039–1052)

House of Poitiers

After 1053, the title of duke of Gascony was held by the dukes of Aquitaine.

- Guy Geoffrey (William VIII of Aquitaine) (1052–1086)

- William IX of Aquitaine (1086–1126)

- William X of Aquitaine (1126–1137)

- Eleanor of Aquitaine (1137–1204)

House of Plantagenet

After 1204, the title of duke of Gascony was held by the kings of England.

The Lord Edward, son of Henry III and later to become King Edward I, was named Duke of Gascony in 1249. On his accession to the throne in 1272, the title was reunited with the kingdom of England.

Footnotes

- "The Duchy of Vasconia" kondaira.net/eng

- Azkarate Garai-Olaun, A. (2004)

- Fredegarius. IV, 54.

- Collins, R. (1990)

- Lewis, Archibald R. (1965). The Development of Southern French and Catalan Society, 718–1050. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 378–379. Retrieved September 11, 2012.

- Monlezun, 342.

- Labarge.

- Higounet 1963, pp. 48–49.

- Higounet 1963, p. 50.

- Collins, relying on the Vita Hludowici. Louis the Pious crossed the Pyrenees and "settled matters" in Pamplona, implying that it fell within his realm, obviously within the Gascon march.

- Collins, Roger (1990). The Basques. Cambridge, Ma: Basil Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-17565-2.

- Douglass, William A.; Douglass, Bilbao, J. (2005) [1975]. Amerikanuak: Basques in the New World. Reno, NV: University of Nevada Press. ISBN 0-87417-625-5. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- Ducado de Vasconia (Auñamendi Encyclopedia)

- El Ducado de Vasconia. Archived 2006-12-08 at the Wayback Machine

Bibliography

- Collins, Roger (1990). The Basques (2nd ed.). London: Blackwell.

- Dunbabin, Jean (2000). France in the Making, 843–1180. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Higounet, Charles (1963). Bordeaux pendant le Haut Moyen Âge. Bordeaux.

- James, Edward (1977). The Merovingian Archaeology of South-West Gaul. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports.

- Jaurgain, Jean de (1898). La Vasconie: Étude historique et critique sur les origines du royaume de Navarre, du duché de Gascogne, des comtés de Comminges, d'Aragon, de Foix, de Bigorre, d'Alava et de Biscaye, de la vicomté de Béarn et des grands fiefs du duché de Gascogne. 2 vols. Pau: Garet.

- Labarge, Margaret (1980). Gascony: England's First Colony, 1204–1453. London: Hamish Hamilton.

- Lewis, Archibald (1965). The Development of Southern French and Catalan Society, 718–1050. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Taylor, Claire (2005). Heresy in Medieval France: Dualism in Aquitaine and the Agenais, 1000–1249. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer.

- Zimmerman, Michel (1999). "Western Francia: The Southern Principalities". In Timothy Reuter (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 3, c. 900 – c. 1024. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 420–55.

External links

- Auñamendi Encyclopedia: Ducado de Vasconia.

- Sedycias, João. História da Língua Espanhola.

- Cawley, Charles, Medieval Lands Project: Gascony., Medieval Lands database, Foundation for Medieval Genealogy,