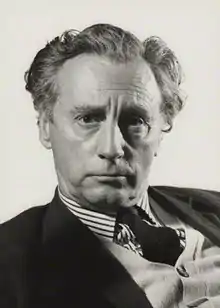

William Douglas Home

William Douglas Home (3 June 1912 – 28 September 1992) was a British dramatist and politician.

Early life

Douglas-Home (he later dropped the hyphen from his surname) was the third son of Charles Douglas-Home, 13th Earl of Home, and Lady Lilian Lambton, daughter of the 4th Earl of Durham. His eldest brother was Sir Alec Douglas-Home, Prime Minister from 1963 to 1964.

He was educated at Eton College and New College, Oxford, where he read History. His first play, Murder in Pupil Room, was performed by his classmates at Eton in 1926 when he was only fourteen.

On 26 July 1951, he married the Hon. Rachel Brand (who later inherited the barony of Dacre), the daughter of Thomas Brand, 4th Viscount Hampden and 26th Baron Dacre, and Leila Emily Seely. They had four children.

Political career

During the Second World War, Douglas-Home contested three parliamentary by-elections as an independent candidate opposed to Winston Churchill's war aim of an unconditional surrender by Germany.[1] The political parties in the wartime Coalition Government had agreed not to contest by-elections when a vacancy arose in a seat held by the other coalition parties. At the Glasgow Cathcart by-election in April 1942, he won 21% of the votes,[2] and at Windsor in June 1942, he won 42%.[3] In April 1944, he came a poor third at the Clay Cross by-election, losing his deposit.[4]

He had intended to contest the St Albans by-election in October 1943, but communications difficulties with the Army Council prevented him from receiving the necessary permission soon enough to meet the deadline for nominations.[5][6]

Post-war, Douglas-Home stood twice as the Liberal Party candidate in Edinburgh South, in a 1957 by-election, and the 1959 general election. He told a story in The Observer Magazine that he took a morning off from the 1959 election campaign to go shooting with his brother, four years before the latter became Conservative Prime Minister in 1963. Alec uncharacteristically missed all the birds in the first drive. When William asked him what was wrong, Alec replied "I had to speak against some bloody Liberal last night!" He had been unaware that the "bloody Liberal" was his own younger brother. William's comment was : "I would have given him a lift if I'd known he was going." Previously, William had briefly been the Conservative Party prospective parliamentary candidate for Kirkcaldy Burghs before resigning over foreign policy differences.

The elections in South Edinburgh had done much to revive Liberal support in the city, following as they did on the first win by a Liberal candidate in Newington Ward in the constituency. Party members were dismayed when he abruptly resigned as a member, apparently because he was not called to speak on a motion on the United Nations during a Party Conference. This was the end of his active political career.

Military service

Despite his opposition to the policy of requiring the unconditional surrender of Nazi Germany he was conscripted into the Army in July 1940 and joined the Buffs (Royal East Kent Regiment).[7] He went to 161 Officer Cadet Training Unit (161 OCTU) in the buildings of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, where one of his colleagues was David Fraser. At Sandhurst, he was critical of the war, which he said had been unnecessary.[8] Douglas-Home was commissioned in the Buffs in March 1941.[9] While an officer he stood in the three parliamentary by-elections.

Douglas-Home was assigned to the 7th Battalion of the Buffs, which was converted to tanks as the 141st Regiment, Royal Armoured Corps. In the Normandy campaign, the 141st Regiment was assigned to I Corps (a British formation) within the First Canadian Army. In August, First Canadian Army was directed to mop up the German forces cut off and trapped in various seaside ports in Normandy and Pas de Calais. In the first week of September 1944, the Allies moved against the port of Le Havre. A German garrison under Colonel Hermann-Eberhard Wildermuth was dug in on the hill overlooking the city. Wildermuth had been ordered by Hitler to defend Fortress Le Havre to the last man, and not to surrender.

When the Allied forces invested the city in advance of the planned aerial bombardment and subsequent assault, Wildermuth asked the British commander if the French civilians could be evacuated from the city, but that request was refused. Lieutenant (acting Captain) Douglas-Home was near Le Havre, awaiting the completion of the aerial bombardment. He was to serve as a liaison officer in Operation Astonia, the Allied attack on Le Havre. On the second day after the aerial bombardment had started, he learned of the German request to evacuate the civilians and the Allied refusal. The consequences of the bombardment were apparent to the waiting Allied forces and Douglas-Home refused to participate in the attack. He gave two reasons:

- The unconditional surrender policy, which he thought compelled the enemy to fight to the end.

- The refusal of civilian evacuation was morally unacceptable to him.

which created a moral obligation for Douglas-Home and he declined to participate.

The aerial bombardment of Le Havre lasted four nights, killed over 2,000 French civilians, 19 German soldiers and levelled the city. The Germans surrendered after two-days' fighting and I Corps moved on to Boulogne, which was also subjected to a heavy aerial bombardment. At that time Douglas-Home, who had been placed under supervision (he did not consider himself at that time to have been "arrested") wrote to the Maidenhead Advertiser and the publication of his letter in the newspaper prompted his formal arrest and detention.

Douglas-Home was charged at a Field General Court Martial held on 4 October 1944 that, when on active service, he disobeyed a lawful command given by his superior officer (contrary to Section 9 (2) of the Army Act 1881). He conducted his own defence. Regrettably neither the Field Court Martial nor Douglas-Home had a copy of the new edition of the Manual of Military Law, which had been prepared and published in April 1944 but not distributed to the troops in Normandy. Prior to April 1944 a British soldier accused of refusing to obey an order had no defence available that the order was illegal. Even had that been brought to the Court-Martial's attention, the grounds of objection by Douglas-Home for refusing to obey Colonel Waddell's order were rejected as he had to admit that the order, to act as a liaison officer, was not illegal. His argument, that he was being required to take part in an event which was morally indefensible, fell on deaf ears. He was convicted, and sentenced to be cashiered and to serve one year's imprisonment with hard labour. The proceedings lasted two hours.[10]

Because of the article in the Maidenhead Advertiser, the Allied forces besieging Calais allowed the civilians to be evacuated from the town before it was subjected to a heavy aerial bombardment and final assault. Dunkirk was allowed to remain in German hands, with the besieged force bottled up, until Germany surrendered on 8 May 1945. In the wake of the publication, the British became sensitive to indiscriminate bombing of occupied cities and towns, although that consideration was not extended to towns and cities in Germany. One of the officers, Second Lieutenant James Wareing, described Douglas Home as follows:

He did not go into any action as far as I am aware and when we were not in action he did nothing. I really don’t know how he came to be there at all in such an elite regiment.

In the field he ate by himself and slept under a tank. He did not seem to be in charge of anyone. However he was put in charge of a group of tanks for the attack on Le Havre. This created something of a situation because he refused to go into action but at the same time was claiming that he could capture Le Havre without firing a single shot. The CO accordingly put him under close arrest under the supervision of another officer.[11]

Another officer described the incident in front of Le Havre as follows:

I was a troop leader in C Squadron 141 RAC and was the escorting officer of William Douglas Home, for two or three days, following his arrest. If my memory serves me correctly he was arrested by order of Major Dan Duffy, our squadron commander and he so ordered the arrest because Captain Douglas Home refused to act as an LO. Home told me that the reason he refused this duty was that if the operation was carried out as planned a large number of French civilians would be killed. He told me that he had offered to negotiate a German surrender but had been refused and consequently declined to serve.[12]

I did not know Home before his secondment to the squadron as an LO for the Le Havre operation as he spent most of his time at RHQ.[13]

Wareing continued

Whilst under arrest Home had written to the editor of the Maidenhead Advertiser who published an exclusive on how Le Havre was captured without firing a single shot. Unlike the letters from other ranks the letters from officers were not subject to 100% censorship but to random screening.

In any event when the War Office saw the newspaper article they immediately investigated the source of the information. The initial upshot was that our CO Lieutenant Colonel H. Waddell was relieved of command and demoted to Major although he continued in combat until we reached Brussels. Here he [Lt Col Waddell] faced a Court Martial and managed to win his case and be reinstated. It was suspected that Home had used his influence with his brother, a member of the Government, the future Lord Home and future Prime Minister, Sir Alec Douglas Home. This could have explained the demotion of our CO. Justice was finally seen to be done because William Home was sent to prison.

He served 8 months, initially in Wormwood Scrubs, then completing his term in Wakefield Prison.[11]

Captain Andrew Wilson, M.C. also served in 141 RAC. In his autobiography Flame Thrower, published in 1956, he recounts this incident and its consequences. Wilson wrote his story deliberately in the third person:

Even when he sailed with the regiment to Normandy, William had continued his private war-against-war. While headquarters were near Bayeux, he had written to the newspapers about some German ambulances shot up by British fighters. And what he had written was true. Wilson had seen the ambulances, riddled with bullets on the Tilly road. Later Waddell had posted William to Duffy’s squadron to take part in the assault on Le Havre. There were thousands of civilians in the town, which was soon to be bombed with 50,000 tons of explosive. William’s moment of decision had at last arrived. On the morning of the battle he returned to regimental headquarters and, finding the C.O. in the act of shaving, told him that be refused to take part. Waddell called a witness. "Will you carry out my order, Home?" – "No, sir".[14]

In 1988, Douglas-Home was roused to challenge his cashiering for disobeying orders, in the wake of an article in The Times, prompted by the election of Kurt Waldheim as the president of Austria. The article attacked Waldheim, who was claimed to have been a Schutzstaffel (SS Officer) in the Greek theatre of war, supervising the loading of prisoners who were being transported north for imprisonment or worse. The article asserted that Waldheim should have disobeyed those orders. It was argued that if Waldheim had disobeyed those orders he would have been punished and probably executed. Douglas-Home accordingly applied for a pardon and was told that he had to petition the War Office to reverse the sentence of the Court Martial. He was supported in his efforts by the military law expert Professor Gerald Draper OBE, who died in the midst of preparing the arguments supporting the petition. His argument was that the attack on Le Havre was morally indefensible, because of the failure to evacuate civilians and that even though he was not engaged directly in attacking those civilians, he was entitled to refuse to take part in the operation or to support it. It was Professor Draper who had discovered that the current edition of the Manual of Military Law had not been available to the October 1944 Field Court Martial. The duty on a soldier not to obey an illegal order, because a morally indefensible operation rendered all orders underpinning it illegal, did not find favour with the War Office, which focused solely on the order, which Douglas-Home had never denied he had disobeyed. Sir David Fraser's take on it was that he did not question Douglas-Home's courage but he had disobeyed an order and he was properly punished for doing so.[15]

The petition was rejected; Douglas-Home had to rely on the judgement of the public as to whether, some three decades after one of the worst civilian tragedies in French history, indiscriminate aerial bombing of civilians in pursuit of wartime objectives was acceptable.[13][16]

Playwright

William Douglas-Home wrote some 50 plays, most of them comedies in an upper class setting.

"In the space of a month or two after his release he wrote two plays which were successful in London in 1947. The first, Now Barabbas, was based on his experience in gaol and in the latter some of the characters were drawn from his family."[11]

Although Douglas-Home was a prolific playwright, his works have neither the depth nor the durability of such near contemporaries as Rattigan or Coward. However, his play The Reluctant Debutante (1955) has been adapted twice into film. The first film, called The Reluctant Debutante, released in 1958, featured Rex Harrison and Sandra Dee, with a screenplay by the playwright himself. The second was released in 2003, under the title What a Girl Wants, starring Amanda Bynes, Colin Firth, and Kelly Preston. The remake features a hereditary peer in the House of Lords who disclaims his title to stand for election to the House of Commons. Douglas-Home's brother Alec was one of the first to do so after the Peerage Act 1963.

As part of the 1975 centennial season of the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company, Douglas-Home wrote a curtain raiser called Dramatic Licence, in which Richard D'Oyly Carte, W. S. Gilbert, and Arthur Sullivan plan the birth of Trial by Jury in 1875. Peter Pratt played Carte, Kenneth Sandford played Gilbert, and John Ayldon played Sullivan.[17]

His other plays included:

- The Chiltern Hundreds (1947)

- Caro William (1952)

- The Cigarette Girl (1962)[18]

- Lloyd George Knew My Father (1972)

Films

Douglas Home's screenwriting credits include:

- Sleeping Car to Trieste (1948)

- The Colditz Story (1955) (dialogue)

- The Reluctant Debutante (1958), remade as What a Girl Wants (2003)

- Follow That Horse! (1960)

Autobiography

- William Douglas Home, Mr Home pronounced Hume; an autobiography, London, Collins, (1979)

References

- William Douglas Home in the Dictionary of National Biography.

- Craig, F. W. S. (1983) [1969]. British parliamentary election results 1918–1949 (3rd ed.). Chichester: Parliamentary Research Services. p. 587. ISBN 0-900178-06-X.

- Craig, p. 294.

- Craig, p. 321.

- Nominations At St. Albans: Would-Be Candidate And Army Council, The Times, Tuesday 5 October 1943, p. 2.

- New M.P. For St. Albans, The Times, Wednesday 6 October 1943; p. 2.

- William Douglas Home. Mr Home pronounced Hume, London, Collins, 1979, p. 51.

- Fraser, David. Wars and Shadows, Memoirs of General Sir David Fraser, pub Allen Lane, 2002. ISBN 0-7139-9627-7 pp. 151–158.

- London Gazette entry

- Smith, R. C. (1998) Refusal of Orders: the case of William Douglas Home. WaiMilHist.

- "A Lesson in Opportunism: With 141 Regiment RAC at Le Havre 1944", by 2nd Lieutenant James Wareing, 141 RAC, the Kentish Regiment (The Buffs), 79th Armoured Division, II British Corps, First Canadian Army, contributed on 19 April 2004.

- Message 3 - A Lesson in Opportunism, posted on 2 February 2005 by phrchilds

- Message 5 - A Lesson in Opportunism, posted on 3 February 2005 by phrchilds

- Wilson, Andrew, Flame Thrower, pub Kimber, 1956.

- Andrew Knapp; "The Destruction and Liberation of Le Havre in Modern Memory" (War In History, 2007)

- See: Hero of Le Havre? BBC Scotland 1991. Primary source: The Hon. William Douglas-Home to JYR in conversation 1988–1991 and in preparation for, conduct of, and in the wake of the Petition for setting aside the conviction and sentence of 4 October 1944 Field Court Martial.

- Forbes, Elizabeth. Kenneth Sandford obituary, The Independent, 23 September 2004.

- http://theatricalia.com/play/avn/the-cigarette-girl

.jpg.webp)