William Goddard (printer)

William Goddard (October 10, 1740– December 23, 1817) was an American patriot and printer, born in New London, Connecticut who lived through the era of the American Revolution. Goddard served as an apprentice printer under James Parker and in 1762 became an early American publisher who eventually founded several newspapers during his lifetime. His mother, father and sister were also involved with printing and publishing in the middle 18th century. For a short term Goddard was also a postmaster of Providence, Rhode Island. Later his newspaper partnership with Benjamin Franklin in Philadelphia would play an important role in the development of Franklin's ideas for a postal system in the soon to be united colonies. Franklin was postmaster of Philadelphia from 1759 to 1775 when he was dismissed by the British Crown for exposing the letters of Massachusetts Governor Thomas Hutchinson. Goddard's association with Franklin while he was serving as the Postmaster in Philadelphia played an important role when Franklin was introducing many of the reforms and improvements needed in the colonial postal system currently in use.[1][2]

William Goddard | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | October 10, 1740 |

| Died | October 23, 1817 (aged 77) |

| Resting place | North Burial Ground |

During the few years leading up to the Revolution Goddard became well noted for the innovations he introduced to the postal system as it came to be employed in mail delivery between the various colonies. Goddard's postal system came about as the result of a series of conflicts involving his newspaper, The Pennsylvania Chronicle, and the Crown Post, a postal administration and mail delivery system that was in use in the British colonies prior to the advent of American independence, under the authority of the British crown. As the idea of revolution began to surface throughout the colonies the British began manipulating the Crown Post (the colonial mail system) by blocking the mail and communications between the various colonies in an effort to prevent them from organizing with each other. The Crown also resorted to the delaying or destroying of newspapers and opening and reading private mail, a form of postal censorship that the British crown considered legal. Goddard's Pennsylvania Chronicle was sympathetic to the revolutionary ideas being put forth by Benjamin Franklin, and others, and so his publication was routinely criticized and under the constant scrutiny of the Crown Post authorities. Franklin had just fallen from grace with the British monarchy by exposing Massachusetts governor Thomas Hutchinson with his own letters, showing him to be in collusion with British efforts to impose more laws and taxes on the colonies in America, and so his involvement with the Chronicle further prompted the Crown in their dealings with Goddard's newspaper. In their effort to see the Pennsylvania Chronicle delivered, Franklin and Goddard persevered and in the midst of British scrutiny would create a separate postal system that ultimately became the postal system in use in the United States today. With the colonies then in dire need of a postal system the committee of correspondence in Boston wrote to the committee in Salem in March 1774 suggesting that an independent postal system be set up, and introduced William Goddard as a more than qualified man for such an undertaking.[1][3][4][5]

As an editor, Goddard involved himself in local slave economies, printing dozens of advertisements for the sale of enslaved people brokered through printing offices.[6]

Early years

William Goddard's parents, both prominent figures in Connecticut society, were Dr. Giles Goddard, a wealthy doctor and postmaster of New London under Benjamin Franklin, and Sarah Updike Goddard, who was also well educated and later ran a family printing business.[7] Soon after Giles Goddard died, Goddard’s mother Sarah Updike moved the family to Providence, Rhode Island, where William opened his first printing business. Here in 1762 he founded the Providence Gazette and was the newspaper's publisher and editor. His friend John Carter, was the newspaper's printer.[8][9] Carter was also taught the printing trade while serving as an apprentice under Benjamin Franklin and who later was appointed Postmaster of Providence by Franklin.[10] In 1767 Goddard founded the Pennsylvania Chronicle. In 1772 he founded Baltimore's first newspaper, The Maryland Journal and later The Baltimore Advertiser.[11] William's older sister was Mary Katherine Goddard who, inspired by her father, was an accomplished printer and the publisher of the Maryland Journal and the Baltimore Advertiser and who later managed her brother William's newspaper, The Pennsylvania Chronicle.[12] In 1775 she was appointed Baltimore’s first postmaster . At the time, her post office was the busiest in the nation. She held this position until 1789.[13] Mary became famous for accepting the task of publishing the first certified copy of the Declaration of Independence in January 1777 that included the signatures of all the state delegates.[14][15] Mary helped him with the Maryland Journal where she remained until 1792.[13]

In 1755 William Goddard started an apprenticeship in the New Haven shop of James Parker, one of the most successful printers in the colonies at the time.[16] In 1762, after the death of her husband, Sarah Goddard helped William, then at the age of 22, set up a printing press in Providence, Rhode Island. With the help of his mother and sister the Goddards published Providence's first newspaper, The Providence Gazette. [4][5] William, growing more restless with revolutionary sentiments, quit the Goddards' printing company in Rhode Island to start a newspaper in Philadelphia under the see of Benjamin Franklin, leaving his sister and mother to run the printing company and Gazette in Rhode Island.

As revolutionary sentiments grew and the revolution with Britain drew closer William’s mother and sister took over operations at the Gazette for William when he began to spend his time and finances undertaking other business matters with Benjamin Franklin and others.[17]

American Revolution

In 1774, in response to the Boston Tea Party, the British Parliament passed what was referred to by the colonists as the Intolerable Acts. Prime Minister Lord North introduced the first measure, the Boston Port Bill, on March 18, 1774. The intrusive bill passed both houses of Parliament with little opposition and was signed by the King at the end of the month.[16] [18] Among other measures the Intolerable Acts closed the port of Boston and radically altered the government of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Many colonists viewed the acts as an arbitrary violation of their rights, and in response they organized the First Continental Congress on September 5 of 1774 at Carpenters' Hall in Philadelphia to establish a representative political body to oppose such laws. When the Boston riots erupted in September 1774, the colonies began to lose trust of the British crown entirely. Since most of the Colonists were born in the colonies at that time and had never seen the actual 'mother land' they had very little sentiment left for King George III or for the British authorities in the colonies. As a result, the Continental Congress was convened at Philadelphia in May 1775 to establish an independent government that would represent the colonists and oppose the arbitrary rules thrust upon them by the Crown.

One of the first questions before the delegates was how to collect and deliver the mail between the various colonies. Franklin who had just returned from England was appointed chairman of a Committee of Investigation to establish a postal system for the colonies. The issue was a pressing one as the existing Crown Post was now routinely manipulating the mail of the colonists prior to the revolution. William Goddard experienced the abuse of authority of the Crown Post in Philadelphia after forming a partnership with Benjamin Franklin to publish the Pennsylvania Chronicle, a paper sympathetic to the revolutionary cause. Goddard was one among several publishers who used private carriers rather than those of the British crown to deliver his Chronicle so as to get the newspapers past the scrutiny of the Crown post who was opposed to Goddard and his Chronicle for their revolutionary sympathies.[19] So adamant was the Crown towards Goddard and the Chronicle that the local Crown postmaster intercepted and refused to deliver mail and other newspapers from other cities and towns to Goddard, depriving him of a critical source of information. The Crown Post also imposed a heavy tax on newspaper delivery. In 1773 the Pennsylvania Chronicle was finally forced to go out of business [20] when the Crown post refused to deliver the newspaper in the mail. Goddard in revolutionary defiance circumvented these efforts by designing an alternative, and distinctly American, postal system and challenged the Crown post, and the principles of free speech that it was supposedly founded on, by creating the Constitutional Post which among other things involved establishing a postal route in and between Philadelphia and New York. Goddard's Constitutional Post came into use right after the commencement of American Revolution at Cambridge, Massachusetts. He chose for his main Post Office to be housed in the London Coffee House in Philadelphia, a meeting place for merchants which became the center of much of the political life of the city prior to and during the American Revolution.[21]

The Constitutional Post

Credit is roundly given to Benjamin Franklin for being the architect of a postal system that is still in use today in the United States. Franklin had made significant contributions to the postal system in the colonies while serving as the postmaster of Philadelphia from 1737 to 1753, and as joint postmaster general of the colonies from 1753 to 1774. Franklin's partnership with William Goddard in 1775 however played an integral role in the development of his ideas for a national postal system that was serve the soon to be United colonies. Goddard's ideas for a postal system were spurred by the Crown Post authorities who were manipulating the mail of the colonies as the revolution became more eminent. Goddard and his associates were forced to create an alternative system that came to be known as The Constitutional Post that would provide mail service to the colonies between New York and Philadelphia.[1] Goddard had presented his plan for a postal system to Congress beforehand on October 5, 1774, nearly two years before the Declaration of Independence was given to England. Congress had to deal with other urgent matters and had to delay Goddard's plan until after the Battles of Lexington and Concord in the Spring of 1775.[22]

On July 26, 1775 the plan, now known as the "Constitutional Post", was adopted and implemented, thus assuring communication between the colonies and keeping them informed of various events during the conflict with Britain. Distrustful of the Crown the colonial populous was turning to and using the postal system now provided by Goddard. Ultimately Goddard and his revolutionary post were so successful they finally forced the Crown post out of business in the American colonies on Christmas Day, 1775.[3] Goddard's Constitutional Post proved to be a success and by 1775, when the Continental Congress met at Philadelphia, Goddard's colonial post was flourishing, and 30 post offices operated between Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and Williamsburg, Pennsylvania. Goddard's plan for a colonial post office would be one that was established and maintained by popular subscription and would be managed and controlled by a private committee that would be elected annually by the subscribers. The committee would appoint postmasters, determine postal routes, hire post-riders and fix the rates of postage. In what was to Goddard an unexpected turn of events, when the Continental Congress on July 26, 1775 authorized a post office run by the government it passed over Goddard and instead named Benjamin Franklin as the first American Postmaster General.[1][22]

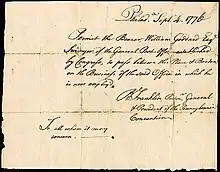

September 4th 1776

Goddard, a one time apprentice of Franklin and who was naturally influenced by his years of experience with the colonial postal system, still felt that he was the general creator of the postal system then in use in the colonies. Naturally he was disappointed when Benjamin Franklin was given the position of Postmaster by the Continental Congress. However he naturally conceded to Franklin, who was 36 years his senior, and to his many years of experience as postmasters and reluctantly but graciously agreed to serve instead as Riding Surveyor for the new U.S. Post Office. Franklin drew up a pass that allowed Goddard to travel at his discretion in his new position. Franklin authored and signed the pass and presented it to Goddard.[3] When the newly created American government under the U.S. Constitution began, the American postal system had about seventy-five post offices and 1,875 miles of post roads to serve a total colonial population of three million people.[1] Franklin served as postmaster for one year at which time the Postmaster's position was given to Richard Bache, the son-in-law of Franklin. Deeply disappointment for being passed over again Goddard resigned. Franklin would later leave the Bonds he had on the Goddards to Bache in his last will and testament of 1788. Franklin died in 1790.

It was not until after the adoption of the Constitution in 1789 that a law passed on September 22, 1789, (1 Stat. 70) which created the federal Post Office under the new government of the United States and authorized the appointment of a Postmaster General who was subject to the direction of the President [23] Four days later President Washington appointed the post of Postmaster General to Samuel Osgood who became the first Postmaster General under the new United States Constitution. Along with the efforts of Benjamin Franklin who pioneered the colonial mail system, Goddard and the Constitutional Post influenced Franklin greatly and helped him in the endeavor of producing a system of mail delivery for the united colonies that is still in use today in the United States and elsewhere.[21]

Later years

While working for the post-office, his sister Mary, in his absence, managed and edited the Maryland Journal single handedly. Because resources were scarce due to the Revolutionary War the paper for the Journal became scarce, so in 1778, Goddard started up a paper-mill in Baltimore, and made his own paper. In its issue of May 5, 1778, appears the following notice: "Rags for the paper-mill near this town are much wanted, and the highest price will be given for them by the printer," and again "Cash will be given in exchange for rags at this office." [4][11][24] Sometime after mid-1778, Goddard was joined at the Maryland Journal by Eleazer Oswald a former American artillery officer. Oswald printed criticisms of George Washington by the disgraced general Charles Lee and this led to public demonstrations against him. Oswald left the Journal and moved to Philadelphia in 1782.[25]

Goddard's relationship with his sister Mary Katherine became strained in the following years, possibly because of financial issues. In January 1784, William's name was added to the colophon of the newspaper and Mary Katherine's name was dropped. William continued to be the head of the newspaper and his sister remained in town as a publisher and postmistress. Late in 1784, William and Mary had published rival almanacs for 1785, which led to William levying attacks at both her almanac and her character. In 1785, she sold her interest in the Maryland Journal which effectively ended her business dealings with William and the newspaper she had helped found.[7]

In 1785, Goddard married Abigail Angell of Johnston, Rhode Island (daughter of Brigadier-General James Angell and Mary Mawney Angell). William and Abigail had 5 children: 4 daughters and 1 son. In 1803 he left Johnston for Providence, so that his children might have more educational advantages. Son, William Giles Goddard, graduated from Brown University in 1812.

Goddard was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1813.[26] Goddard lived in Providence until his death, December 22, 1817, aged seventy-seven years. He is buried in the North Burial Ground at Providence, Rhode Island.[11]

See also

References

- American Heritage Magazine, The U.S. Post Office, 1775-1974

- New York Times/ABOUT.COM

- Smithsonian National Postal Museum

- Journalism Department University of Rhode Island

- The Library of Congress

- Taylor, Jordan E. (2020-07-17). "Enquire of the Printer: Newspaper Advertising and the Moral Economy of the North American Slave Trade, 1704–1807". Early American Studies. 18 (3): 287–323. doi:10.1353/eam.2020.0008. ISSN 1559-0895.

- Baltimore Heritage

- Eighteenth-Century American Newspapers in the Library of Congress

- Later, on September 27, 1787, the Providence Gazette under Carter printed the U.S. Constitution on the front page.

- Rhode Island Historical Society

- Culter, William Richard. (1914). New England families, genealogical and memorial: Volume 4. Lewis Historical Publishing Company, New York. p. 1835.

- Vaughn, Stephen L. (2008). Elmira: Encyclopedia of American journalism. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, New York, NY. p. 424. ISBN 978-0-415-96950-5.

- Maryland State Archives

- Distinguished Women of Past and Present

- Miner, William Goddard: Newspaperman, 1962 p.166

- 'Encyclopedia.com'

- Mary Goddard; Smithsonian National Postal Museum

Women in the U.S. Postal System - American Public University

- Dalphy I. Fagerstrom, Bethel College, Saint Paul

- "William Goddard, Journalist; Great-Grandparent of Mr. C. Oliver Iselin's Bride. Full article links to PDF file". New York Times. July 15, 1894. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- Independence Hall Association, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, founded 1942

- HISTORY.COM

- U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

- The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography © 1950 The Historical Society of Pennsylvania - JSTOR

- Boatner, Mark M. III (1994). Encyclopedia of the American Revolution. Mechanicsburg, Pa.: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-0578-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link), 820

- American Antiquarian Society Members Directory

External links

Bibliography

- Goddard, William G. (1870). William G. Goddard (ed.). The political and miscellaneous writings of William G. Goddard, Volume 1. Sidney S. Rider and Brothers, Providence, RI. p. 568. -- url

- Miner, Ward L. (1962). William Goddard: Newspaperman. Duke University Press. p. 223. -- url