Postal censorship

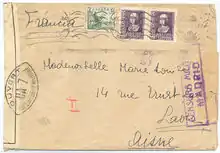

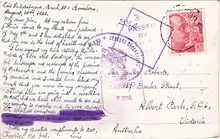

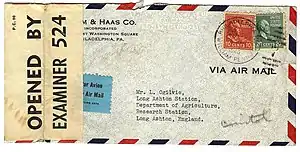

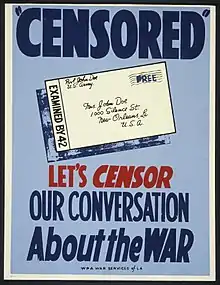

Postal censorship is the inspection or examination of mail, most often by governments. It can include opening, reading and total or selective obliteration of letters and their contents, as well as covers, postcards, parcels and other postal packets. Postal censorship takes place primarily but not exclusively during wartime (even though the nation concerned may not be at war, e.g. Ireland during 1939–1945) and periods of unrest, and occasionally at other times, such as periods of civil disorder or of a state of emergency. Both covert and overt postal censorship have occurred.

Historically, postal censorship is an ancient practice; it is usually linked to espionage and intelligence gathering. Both civilian mail and military mail may be subject to censorship, and often different organisations perform censorship of these types of mail. In 20th-century wars the objectives of postal censorship encompassed economic warfare, security and intelligence.

The study of postal censorship is a philatelic topic of postal history.

Military mail

Military mail is not always censored by opening or reading the mail, but this is much more likely during wartime and military campaigns. The military postal service is usually separate from civilian mail and is usually totally controlled by the military. However, both civilian and military mail can be of interest to military intelligence, which has different requirements from civilian intelligence gathering. During wartime, mail from the front is often opened and offending parts blanked or cut out, and civilian mail may be subject to much the same treatment.

Prisoner-of-war and internee mail

Prisoner-of-war and internee mail is also subject to postal censorship, which is permitted under Articles 70 and 71 of the Third Geneva Convention (1929–1949). It is frequently subjected to both military and civil postal censorship because it passes through both postal systems.

Civilian mail

Until recent years, the monopoly for carrying civilian mails has usually been vested in governments,[1][2] and that has facilitated their control of postal censorship. The type of information obtained from civilian mail is different from that likely to be found in military mail.

Countries known to have enacted postal censorship

Throughout modern history, various governments, usually during times of war, would inspect mail coming into or leaving the country so as to prevent an enemy from corresponding with unfriendly entities within that country.[3]:22 There exist also many examples of prisoner of war mail from these countries which was also inspected or censored. Censored mail can usually be identified by various postmarks, dates, postage stamps and other markings found on the front and reverse side of the cover (envelope). These covers often have an adhesive seal, usually bearing special ID markings, which were applied to close and seal the envelope after inspection.[3]:55–56

Britain and American colonies

During the years leading up to the American Revolution, the British monarchy in the American colonies manipulated the mail and newspapers sent between the various colonies in an effort to prevent them from being informed and from organizing with each other. Often mail would be outright destroyed.[4][5]

American Civil War

During the American Civil War both the Union and Confederate governments enacted postal censorship. The number of Union and Confederate soldiers in prisoner of war camps would reach an astonishing one and a half million men. The prison population at the Andersonville Confederate POW camp alone reached 45,000 men by the war's end. Consequently, there was much mail sent to and from soldiers held in POW installations. Mail going to or leaving prison camps in the North and South was inspected both before and after delivery. Mail crossing enemy lines was only allowed at two specific locations.[6][7][8]

Pre-World War I

In Britain, the General Post Office was formed in 1657, and soon evolved a "Secret Office" for the purpose of intercepting, reading and deciphering coded correspondence from abroad. The existence of the Secret Office was made public in 1742 when it was found that in the preceding 10 years the sum of £45,675 (equivalent to £6,332,000 in 2016[9]) had been secretly transferred from the Treasury to the General Post Office to fund the censorship activities.[10] In 1782 responsibility for administering the Secret Office was transferred to the Foreign Secretary and it was finally abolished by Lord Palmerston in 1847.

During the Second Boer War a well planned censorship was implemented by the British that left them well experienced when The Great War started less than two decades later.[11] Initially offices were in Pretoria and Durban and later throughout much of the Cape Colony as well a POW censorship[12] with camps in Bloemfontein, St Helena, Ceylon, India and Bermuda.[13]

The British Post Office Act 1908 allowed censorship upon issue of warrants by a secretary of state in both Great Britain and in the Channel Islands.[14]

World War I

Censorship played an important role in the First World War.[15] Each country involved utilized some form of censorship. This was a way to sustain an atmosphere of ignorance and give propaganda a chance to succeed.[15] In response to the war, the United States Congress passed the Espionage Act of 1917 and Sedition Act of 1918. These gave broad powers to the government to censor the press through the use of fines, and later any criticism of the government, army, or sale of war bonds.[15] The Espionage Act laid the groundwork for the establishment of a Central Censorship Board which oversaw censorship of communications including cable and mail.[15]

Postal control was eventually introduced in all of the armies, to find the disclosure of military secrets and test the morale of soldiers.[15] In Allied countries, civilians were also subjected to censorship.[15] French censorship was modest and more targeted compared to the sweeping efforts made by the British and Americans.[15] In Great Britain, all mail was sent to censorship offices in London or Liverpool.[15] The United States sent mail to several centralized post offices as directed by the Central Censorship Board.[15] American censors would only open mail related to Spain, Latin America or Asia--as their British allies were handling other countries.[15] In one week alone, the San Antonio post office processed more than 75,000 letters, of which they controlled 77 percent (and held 20 percent for the following week).[15]

Soldiers on the front developed strategies to circumvent censors.[16] Some would go on "home leave" and take messages with them to post from a remote location.[16] Those writing postcards in the field knew they were being censored, and deliberately held back controversial content and personal matters.[16] Those writing home had a few options including free, government-issued field postcards, cheap, picture postcards, and embroidered cards meant as keepsakes.[17] Unfortunately, censors often disapproved of picture postcards.[17] In one case, French censors reviewed 23,000 letters and destroyed only 156 (although 149 of those were illustrated postcards).[17] Censors in all warring countries also filtered out propaganda that disparaged the enemy or approved of atrocities.[15] For example, German censors prevented postcards with hostile slogans such as "Jeder Stoß ein Franzos" ("Every hit a Frenchman") among others.[15]

Between the wars

Following the end of World War I, there were some places where postal censorship was practiced. During 1919 it was operating in Austria, Belgium, Canada, German Weimar Republic and the Soviet Union as well as other territories.[18]:126–139 The Irish Civil War saw mail raided by the IRA that was marked as censored and sometimes opened in the newly independent state. The National Army also opened mail and censorship of irregulars' mail in prisons took place.[19]

Other conflicts during which censorship existed included the Third Anglo-Afghan War, Chaco War,[18]:138 were the Italian occupation of Ethiopia (1935–36)[20] and especially during the Spanish Civil War of 1936–1939.[18]:141[21]

World War II

During World War II, both the Allies and Axis instituted postal censorship of civil mail. The largest organisations were those of the United States, though the United Kingdom employed about 10,000 censor staff while Ireland, a small neutral country, only employed about 160 censors.[22]

Both blacklists and whitelists were employed to observe suspicious mail or listed those whose mail was exempt from censorship.[22]

Imperial Censorship

British censorship was primarily based in the Littlewoods football pools building in Liverpool with nearly 20 other censor stations around the country.[23] Additionally the British censored colonial and dominion mail at censor stations in the following places:

- Dominions: Australia, Canada, Newfoundland, New Zealand, Southern Rhodesia (not a dominion but supervised by the Dominion office) and Union of South Africa

- Colonies: Aden, Antigua, Ascension Island, Bahamas, Bahrain, Barbados, Bermuda, Ceylon, Cyprus, Dominica, Egypt, Falkland Islands, Fiji, Gambia, Gibraltar, Gilbert and Ellice Islands, Gold Coast, Grenada, British Guiana, British Honduras, Hong Kong, Jamaica, Kenya, Malaya, Malta, Mauritius, Montserrat, New Hebrides, Nigeria, North Borneo, Northern Rhodesia, Nyasaland, Palestine, Penang, St. Helena, St. Lucia, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Vincent, Sarawak, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, British Solomon Islands, Somalia, Sudan, Tanganyika, Trinidad, Tonga, Uganda, Virgin Islands and Zanzibar,

United States

In the United States censorship was under the control of the Office of Censorship whose staff count rose to 14,462 by February 1943 in the censor stations they opened in New York, Miami, New Orleans, San Antonio, Laredo, Brownsville, El Paso, Nogales, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, Chicago, San Juan, Charlotte Amalie, Balboa, Cristóbal, David, Panama and Honolulu.

The United States blacklist, known as U.S. Censorship Watch List, contained 16,117 names.[24]

Neutral countries

Neutral countries such as Ireland,[22] Portugal and Switzerland also censored mail even though they were not directly involved in the conflict.

Post-World War II

Following the end of hostilities in Europe, Germany was occupied by the Allied Powers in zones of control. Censorship of mail that had been impounded during the Allies advances, when postal services were suspended, took place in each zone though by far the least commonly seen mail is from the French Zone.[25]:78 When most of the backlog had been cleared regular mail was controlled as well as in occupied Austria.[25]:101–107 Soviet zone mail is considered scarce.[25]:92, 109

In the German Democratic Republic, the Stasi, established in 1950, were responsible for the control of incoming and outgoing mail; at their height of operations, their postal monitoring department controlled about 90,000 pieces of mail daily.[26]

Several small conflicts saw periods of postal censorship, such as the 1948 Palestine war,[27] Korean War (1950–1953), Poland (1980s), or even the 44-day Costa Rican Civil War in 1948.[28]

See also

References and sources

Notes

- Sylvain Bacon; Michael S. Coughlin (15 May 2004). "Achieving High Performance in A Competitive Postal Environment". Pushing the Envelope. montgomeryresearch.com. Archived from the original on 22 June 2009. Retrieved 21 August 2006.

- The (US) Postal Monopoly (retrieved 21 August 2006)

- Herbert, E.S (editor); des Graz, C.G. (editor) (1952). History of the Postal and Telegraph Censorship Department 1938–1946. London: Home Office. pp. 55–56.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Carson, Gerald (October 1974). "The U.S. Post Office, 1775–1974". American Heritage. 25 (6). ISSN 0002-8738. Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- New York Times/ABOUT.COM

- "American Civil War: POW camp at Andersonville". New York Times, about-com. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- "Civilian Flag-of-Truce Covers". S.N.P.M.

- "Prisoner mail exchange". Prisoner of War mail, Smithsonian National Postal Museum. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- United Kingdom Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the Measuring Worth "consistent series" supplied in Thomas, Ryland; Williamson, Samuel H. (2018). "What Was the U.K. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Hemmeon, Joseph Clarence (1912). The history of the British post office. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University. p. 46.

- Fiset, Louis (2001). "Return to Sender: U.S. Censorship of Enemy Alien Mail in World War II". Prologue Magazine Spring 2001, Vol. 33, No. 1. National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- "Collecting Interests: Censorship". Anglo-Boer War Philatelic Society. 2014. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- Fremont-Barnes, Gregory (2003). The Boer War 1899–1902. Wellingborough: Osprey Publishing. p. 82. ISBN 9781841763965.

- "Postal and Telegraph Censorship Department, predecessors and successor: Papers". The National Archives. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- Demm, Eberhard. "Censorship | International Encyclopedia of the First World War (WW1)". International Encyclopedia of the First World War. Archived from the original on 20 January 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- "Circumventing the censorship and "self-censorship"". The World of the Habsburgs. Archived from the original on 21 December 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- Hanna, Martha (8 October 2014). "War Letters: Communication between Front and Home Front | International Encyclopedia of the First World War (WW1)". International Encyclopedia of the First World War. Archived from the original on 26 March 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- Wolter, Karl Kurt (1965). Die Postzensur: Band I - Vorzeit, Früheit und Neuzeit (bis 1939). Munich: Georg Amm.

- Dulin, Cyril I. (1992). Ireland's Transition: The Postal History of the Transitional Period 1922–1925. Dublin: MacDonnell Whyte Ltd. pp. 94–97. ISBN 0-9517095-1-8.

- "Between the Wars – Italian Occupation of Ethiopia". Postalcensorship.com. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- Shelley G., Ronald (1967). The Postal History of the Spanish Civil War 1936–1939. Hove.

- Ó Drisceoil, Donal (1996). Censorship in Ireland, 1939–1945. Cork University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-85918-074-7.

- Herbert, E.S.; des Graz, C.G., eds. (1952). History of the Postal and Telegraph Censorship Department 1938–1946 Volume I & II (CCSG reprint 1996). Home Office. p. 355.

- "Civilian Agency Records: Records of the Office of Censorship (RG 216)". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- Beede, Benjamin R. (2005). From the Reichspost to Allied Occupation. Frankfurt am Main: Buckhard Schreider.

- "Ministerium für Staatssicherheit" (in German). Gedenkstätte Berlin. 2015. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- Parren, Marc (July 2012). "Post WWII – Syrian Censorship During 1948". Civil Censorship Study Group Bulletin. Bristol: Civil Censorship Study Group. 38 (169): 32–37.

- Mayo, Dann (July 2012). "Post WWII – Small Event Censorship – Costa Rica 1948 & 1955". Civil Censorship Study Group Bulletin. Bristol: Civil Censorship Study Group. 39 (175): 125.

Books

- Mark FRPSL, Graham (2000). British Censorship of Civil Mails During World War I. Bristol, UK: Stuart Rossiter Trust. ISBN 0-9530004-1-9.

- Little, D.J. (2000). British Empire Civil Censorship Devices, World War II: Colonies and Occupied Territories - Africa, Section 1. UK: Civil Censorship Study Group. ISBN 0-9517444-0-2.

- Torrance, A.R., & Morenweiser, K. (1991). British Empire Civil Censorship Devices, World War II: United Kingdom, Section 2. UK: Civil Censorship Study Group. ISBN 0-9517444-1-0.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Stich, Dr. H.F., Stich, W., Sprecht, J. (1993). Civil and Military Censorship During World War II. Canada: Stich, Stich and Sprecht. ISBN 0-9693788-2-3.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Wolter, Karl Kurt (1965). Die Postzensur: Band I - Vorzeit, Früheit und Neuzeit (bis 1939). Munich: Georg Amm.

- Herbert, E.S.; des Graz, C.G., eds. (1996). History of the Postal and Telegraph Censorship Department 1938–1946 Volume I & II. Civil Censorship Study Group by permission of Public Record Office, Kew, UK.

- Harrison, Galen D. (1997). Prisoners' Mail from the American Civil War. Dexter, MI: Galen D. Harrison (?).

Papers & reports

- Pfau, Ann (27 September 2008). "Postal Censorship and Military Intelligence during World War II" (PDF). National Postal Museum. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- Price, Byron (15 November 1945). "Report on the Office of Censorship" (PDF). United States Government Printing Office. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- Whyman, Susan E. "Postal Censorship in England 1635–1844" (PDF). Postcomm. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 February 2008. Retrieved 19 February 2008.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Postal censorship. |

- History comes to life with censored covers Linn's Stamp News (Wayback Machine archived link)

- Why Mail Censorship is Vital to Britain (1916) Interview with Lord Robert Cecil, British Minister of Blockade (Wayback Machine archive link)

- Postalcensorship.com Website devoted to postal censorship with many examples of censored mail

- Civil Censorship Study Group

- Forces Postal History Society

- Military Postal History Society